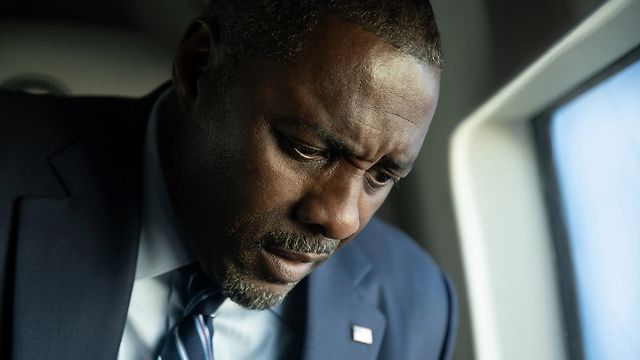

Now, with A House of Dynamite, Bigelow returns to the present day with a terrifying what-if scenario that she executes with the utmost precision—and, as the doomsday clock ticks down toward zero, entirely without mercy. What makes the film so uncommonly chilling is the sense of abstraction that creeps in as this missile bears down on its target; as these characters assess computer screens and countdown clocks from secure locations that will not directly experience the fallout of their failing procedures and protocols, Bigelow exposes the obfuscation of reality that results from such an unaccountable system, the structural ways that power is insulated from consequence—not inadvertently but as a matter of policy.

As Matt observes, the director’s latest is “an epic nightmare of verisimilitude, of cooler heads being systematically—perhaps even by sheer dint of definition—disallowed from prevailing.” Jacob, meanwhile, calls it “Bigelow’s Fail Safe, only it’s a tragedy of errors, in which escalation seems to be the only end game,” adding that “no one can find such great depth of meaning in procedural detail quite like Bigelow.”

As a filmmaker, Bigelow’s taut and tough-minded sensibility has also consistently won her praise from industry peers. No less than Michael Mann named The Hurt Locker as one of his fourteen favorite films “for its brilliantly directed performances, as penetrating into the psyches of combatants moving progressively, inexorably closer and closer to annihilation.” (Of Bigelow, he told Letterboxd, “I thought her work was so incisive and quite brilliant. She’s really a formidable director.”) Pop star Charli XCX put it even more simply on her Letterboxd account: “Thank God for Kathryn Bigelow <3”

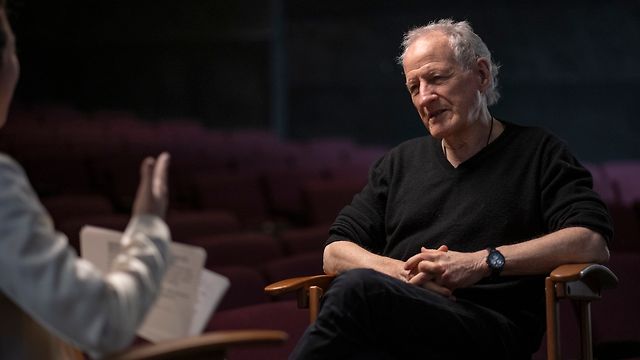

With A House of Dynamite streaming now on Netflix, Bigelow spoke via Zoom about her continued fascination with the US military-industrial complex, the disturbing dormancy of the nuclear-war thriller and her cinematic lodestars.