Here's a couple of the things I will cast in the next month or so. Both are made of lost wax, which seemed to be the method used for surviving medieval examples

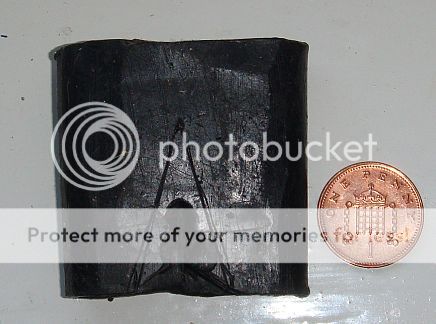

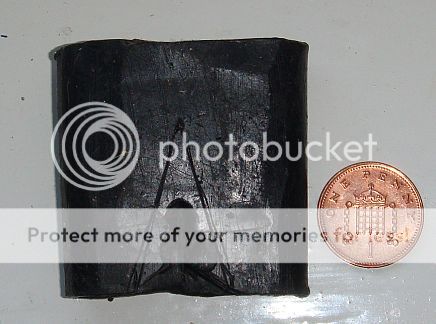

First, a dagger scabbard chape,

Wax original.( Read more...Collapse )

Wax original.( Read more...Collapse )

Then here it is covered in slip, i.e. clay in water, so as to make a nice smooth interior of the mould:

I see that some of the wax colouring is leaking out, presumably it is water soluble but it doesn't really matter.

Then there's this dagger locket, made to fit one of my dagger scabbards. (as an aside, most of our re-enactment daggers are far larger than medieval ones. I think this is partly beacuse we're on average taller, and also because people like bigger things, and the makers aren't paying so much attention to originals)

It is copied from an original, but much smaller one, found in or near Salisbury.

Here it is covered in slip:

The sticky outy bits are the loops for it to be suspended from a belt by. Note the lumps of wax at the top, they are acting as ingates and vents for the metal when it is poured in.

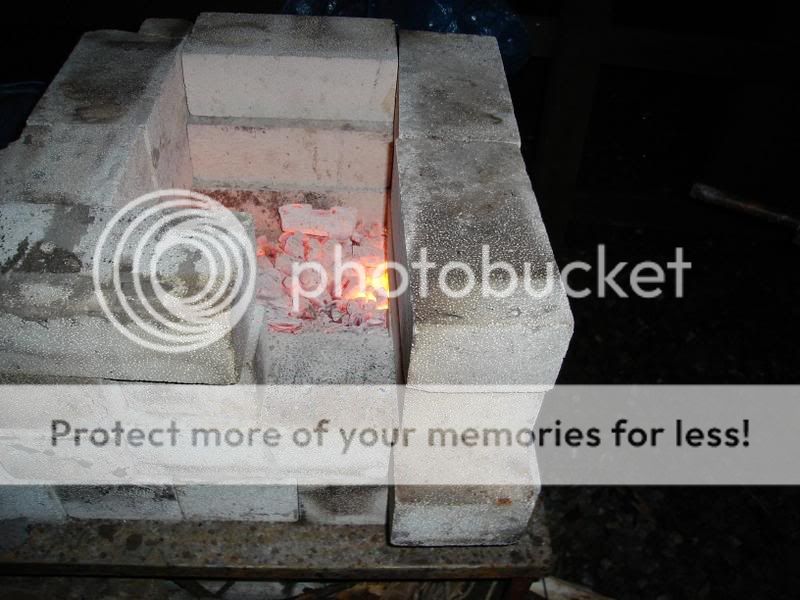

Both these moulds now need to be surrounded by the usual sand, clay and horse dung mix that I use, although I shouldn't make it too thick. Once that is done they will be dried, the wax melted out and then fired. Finally I'll pour metal into them. This is a long process, especially when you are trying to do it authentically.

First, a dagger scabbard chape,

Wax original.( Read more...Collapse )

Wax original.( Read more...Collapse )Then here it is covered in slip, i.e. clay in water, so as to make a nice smooth interior of the mould:

I see that some of the wax colouring is leaking out, presumably it is water soluble but it doesn't really matter.

Then there's this dagger locket, made to fit one of my dagger scabbards. (as an aside, most of our re-enactment daggers are far larger than medieval ones. I think this is partly beacuse we're on average taller, and also because people like bigger things, and the makers aren't paying so much attention to originals)

It is copied from an original, but much smaller one, found in or near Salisbury.

Here it is covered in slip:

The sticky outy bits are the loops for it to be suspended from a belt by. Note the lumps of wax at the top, they are acting as ingates and vents for the metal when it is poured in.

Both these moulds now need to be surrounded by the usual sand, clay and horse dung mix that I use, although I shouldn't make it too thick. Once that is done they will be dried, the wax melted out and then fired. Finally I'll pour metal into them. This is a long process, especially when you are trying to do it authentically.

Leave a comment