Today marks thirty years since the publication of David Foster Wallace’s failed entertainment, Infinite Jest. Click away if you must–but I hope you will stay.

The anniversary snuck up on me. In my defense, I have also been consumed with the publication of my own personal big book (more about that in a minute), and managing both a few winter storms and the world’s first four-thousand day-long January. There’s been a lot going on.

But since the book had such an impact on my own personal life and work, I have got to have something to say about it. So, provoked by Hermione Hoby’s excellent reassessment this week at The New Yorker, I’ll try.

This book landed smack in my sweet spot: right at the end of that part of my life when my sweet spot was still accepting applications, wide-eyed and willing.

I have read it multiple times, alone and with others (especially with others). I have read it in hardback first edition, in trade paperback, upon a Kindle, once in its entirety upon the tiny screen of an iPhone (!). I have taught it to two Honors College seminars, and would do still if the English dept hadn’t gotten wind of my efforts and wondered mildly if I had the bona fides to do so (no, but try me).

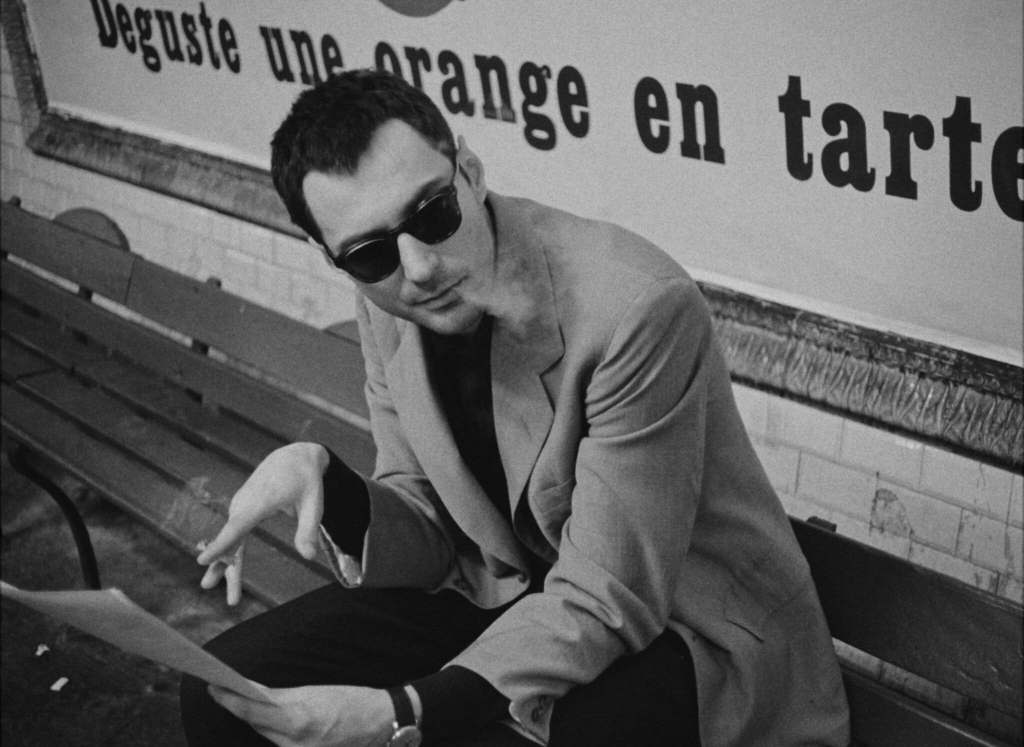

I own an autographed first edition, which he signed in the middle of the tour when I saw him read at Politics & Prose just a few days before he met David Lipsky. He read about Lyle, and the woman who said she’d come, I think.

I have even read much of the the terrific scholarship emerging around it, and made some small CV bones of it.

I have not pressed the book on many people. (Except my ninth grade English students in 1996, whom I subjected to period-long readings from the book that spring. Apologies?) Recommending a book is always a big risk, and even bigger when the book is massively long (it is) and infamously difficult (not really) and a bit of a cultural taser (ymmv).

But I have lived with it myself for thirty years, through many of my own changes and shifts. It was present at my creation as an adult as surely I was present at its. So it is my ur-text: the book against which I measure the ambition, the impact, and the faults of nearly anything else I read. Respect must be paid.

Hoby does the honors, so well. Born in 1985, she is sixteen years younger than me (and three years younger than those ninth graders). Her take is well-programmed. We suppose we can know what this book meant to folks like me who hoovered it up in our twenties, and what it means now in our fifties, if anyone cares. But what does it mean now, to the youngs?

Well, she writes directly to the heart of IJ’s maintenance in the cultural consciousness (mostly by those who have not read it) as a red flag for self-involvement, for “performative reading,” for male toxicity. And plaintively wonders:

The occasion is a moment to ask how a novel that mourns addiction and venerates humility and patience became a glib cultural punch line…At a thousand and seventy-nine pages, Infinite Jest has become a one-liner.

Amen, sister. It’s not right that a book that works so hard to make a case for simple connection between people, and depicts so vividly the horrorshows that nonetheless keep us apart, would be reduced thus.

Part of it is conflation of book and flawed author, who of course is not around to speak to our evolving takes on the work for good or ill–or evolve himself, like so many fathers, Shakespearean and other. He is gone and the book remains. If we still want to read it, we are on our own to explore why.

I bought my first edition of Infinite Jest at a chain book store in Dupont Circle, selecting my copy carefully from a teetering ziggurat of blue-sky-with-white-clouds covers that dominated the entrance. It was expensive–thirty bucks, on a beginning teacher’s salary!—but I dropped the coin.

I did so at the urging and in the company of my best friend at the time, a fellow teacher at my first school. He was nine years older than me (still is, strangely), and had already become a sort of pace horse for me in the three years I had known him.

He showed me a way of being an adult that I had never seen up close, and didn’t really know was possible. He was deadly serious about the things I was beginning to care about more than air and water: music, stories, teaching, beauty where you found it. He had taught at this place right out of college, like me, then left to go to a really good law school and become a big deal lawyer.

And then he had dramatically quit the law and come back to teaching—because he had come to realize that some ways of spending your life deadened your soul, and some ways expanded it. This made an abiding impression on me. When you figure out what matters, perhaps you should immediately begin devoting all your energy to it, hang the cost.

This relationship matters most here because it points to a type of experience that IJ catalyzed for me. It could have NOT been a big hard smartypants book that my friend and I had in common. It could have been working on our cars on the weekend, or playing in a band together (actually, we did that too), or playing D&D or rock climbing or building houses. Youngish people have lots of salubrious things they find to get into together.

But it wasn’t: it was reading a hard book that was heady and inane, hilarious and heartbreaking, in turns—sometimes on the same page. Reading alone to ourselves (like we all do, if elementary school works), and then talking about what we had read.

That spring, we mostly kept in step with each other, not spoiling events coming up if one of us pulled ahead by a few pages. We tried out theories about whether this character or plot point contributed to the whole huggermugger or would be a red herring; we reminded each other of what someone who sounded suspiciously like this character actually said in a group conversation a hundred pages back.

Put another way: we made an asynchronous individual experience into a time-wedded shared one. If the way to make friends is in fact going through stuff with people—well, we went through it together, for months. We remain close friends despite distance and decades, with the book remaining a touchstone of our shared formative time even as other experiences have followed for each of us.

(Do the youngs still have these experiences? Do the young men? That’s another post. The double bind especially young men find themselves in when they run the risk of being tarred “LitBros” for caring inordinately about something that speaks to them.)

I think that the best of these relationships happen around actual made-by-human texts, not engine blocks or soccer pitches. Texts that are too big to be held in your own head alone. Texts that insist on stopping time for you until you find someone else to help you make it real. Those texts can be films, too, I know–or videogames, I hear. (My son chats “on the phone” online with a friend while they build and explore Minecraft realms together. That sure sounds like kind of the same thing.)

But caveat: the shared text has to be too much to be managed alone.

And that is why it has to be human-made.

Because tech can give you too much, too–but why would you care to spend time with its excesses, when there is no too-much human behind the scenes to try to know?

My strongest memory of meeting Wallace in DC was looking at his head and wondering: this all came out of that? What structured it and contained it? What, even after 1079 pp, has not yet been said? How unfathomably broad the backfields inside each of our skulls* really are, bandanna-wrapped or not.

Making sense of that landscape is usually beyond us. As I read the early critical responses to IJ, I notice again and again how Wallace is taken to task for his “excess”. Again, Wikipedia:

Some early reviews, such as Michiko Kakutani‘s in The New York Times, were mixed, recognizing the inventiveness of the writing but criticizing the length and plot. She called the novel “a vast, encyclopedic compendium of whatever seems to have crossed Wallace’s mind.” In the London Review of Books, Dale Peck wrote of the novel, “… it is, in a word, terrible. Other words I might use include bloated, boring, gratuitous, and—perhaps especially—uncontrolled.”[ Harold Bloom, Sterling Professor of Humanities at Yale University, called it “just awful” and written with “no discernible talent” (in the novel, Bloom’s own work is called “turgid”). In a review of Wallace’s work up to the year 2000, A. O. Scott wrote of Infinite Jest, “[T]he novel’s Pynchonesque elements…feel rather willed and secondhand. They are impressive in the manner of a precocious child’s performance at a dinner party, and, in the same way, ultimately irritating: they seem motivated, mostly, by a desire to show off.”

A.O., my man! Simmer down!

Many of these opinions became revised with time. Criticism of course usually happens on deadline, when even an advance copy only comes a couple of weeks before an assessment is due. A big work, one that overflows convention and expectation, must be resented on some level–must be punished for overflowing, maybe. As Joe Jackson says, on a near-perfect and almost-entirely-forgotten album:

And when I die and go to pure pop heaven

The angels will gather around

And ask me for my whole life story

And for that fabulous sound

But I know they’re gonna stop me

As I start going through every line

And say please–not the whole damn album

Nobody has that much time.

Just the hit single.

I needed every month of the last thirty years to make sense of this book, deeply and gratefully. Its excess is its economy: messy, overbearing, too much. Human, at our very best.

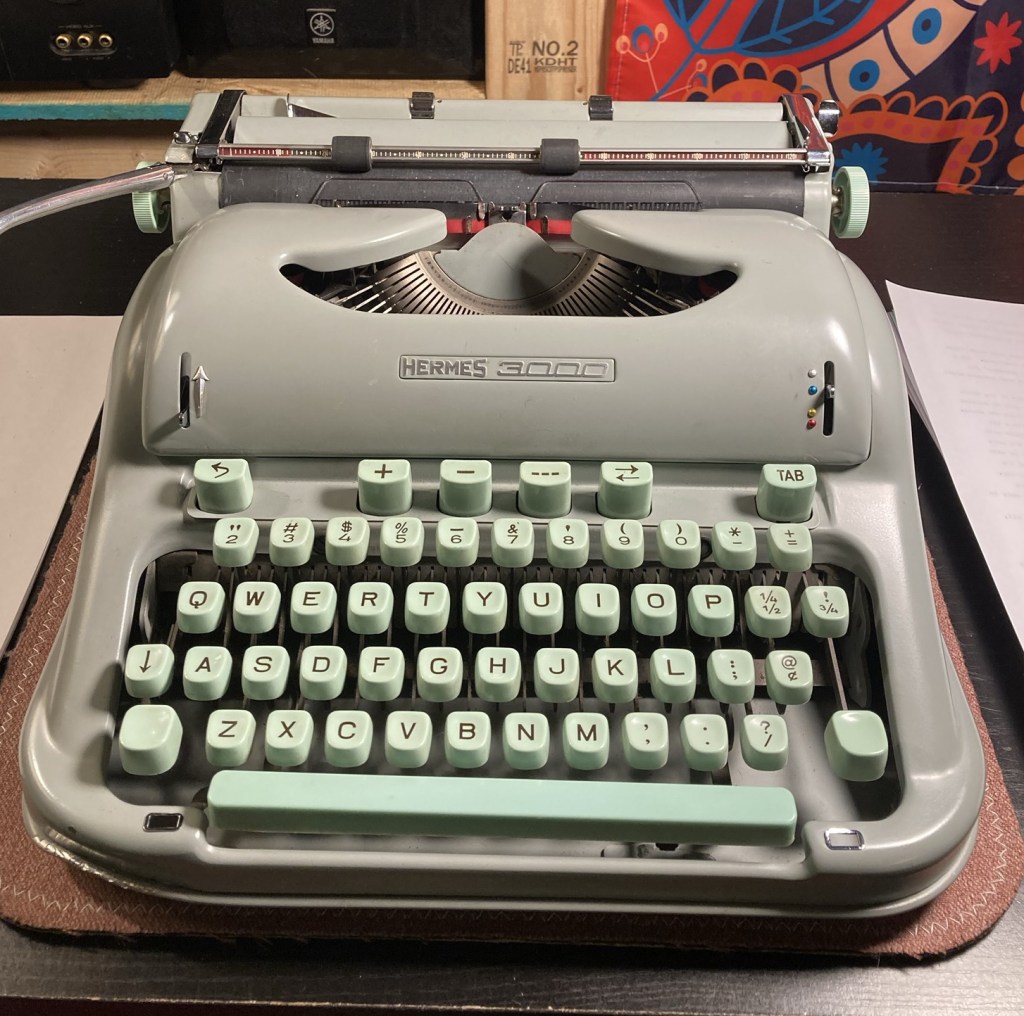

My own book could only happen once I gave myself two permissions:

To say exactly what I meant, for exactly the reader I wanted to hear it, however it came out on the page.

And to feel and speak the anger I felt–and still feel–toward every mechanistic, logical, algorithmic attempt to rationalize and make more manageable our real human experiences in the name of efficiency, economy, and “accountability” that rarely brings us any returns.

To be against such things is inevitably to be for excess, for mess, for reality exactly as it is.

And I can see that, at this point, IJ’s lasting legacy for me has been permission to do my own thing as fulsomely as Wallace did his.

I’m not Wallace, and neither are you…but my words can find the reader who needs them, too, as surely as his did. And as surely as yours can.

I don’t remember if I thanked him in the acknowledgments, but if not I thank him here.**

And I hope you find your own DFW too. Your own permission; your own cage that liberates and sustains both.

*Permit me but one footnote, ’tis but a wafer thin: skulls are structures that contain what is precious so that it can thrive. What happens to us without the right structures–and what can happen, if we find and commit to them– is one of my favorite concatenating themes in the Sierpiński Triangle of the book. Without skulls, without frameworks, without principles, without cages, we are lost, or at least seriously compromised. Do not draw to yourself weight that exceeds your own weight. Find your cage.

** Yeah, I did.

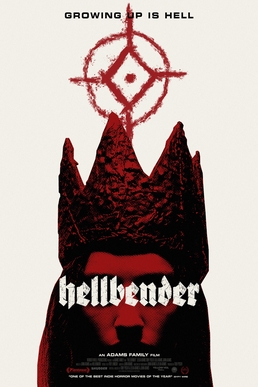

Image approximating cover of first printing borrowed from Mental Floss, with thanks.