Fiber gets talked about a lot in health and nutrition, and most people agree it’s “good.” But beyond that, the details are fuzzy. There’s still confusion about what fiber actually is, the different types, and how each one works in the body.

In this article, I’ll cover the types of fiber, how they interact in your body, and how to consider fiber intake based on your goals.

Let’s dig in.

What is fiber?

Dietary fiber is a bit tricky to define because even academic sources describe it differently. At its core, fiber refers to the indigestible parts of plant-based foods.

| A basic categorization of dietary fiber | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of fiber | Source | Water interaction | Common functionality |

| Soluble fiber | Mostly found in the inner flesh or pulp of fruits, vegetables, legumes, and some grains | Mostly absorbs water | Some types form gels that slow digestion and help regulate blood sugar and cholesterol. Others ferment in the gut and support beneficial bacteria. |

| Insoluble fiber | Mostly found in the outer husks, shells, and tough outer layers of plant foods | Mostly doesn’t absorb water | Adds bulk and helps food move through the digestive tract. Doesn’t ferment much, and is mostly involved in bowel regularity. |

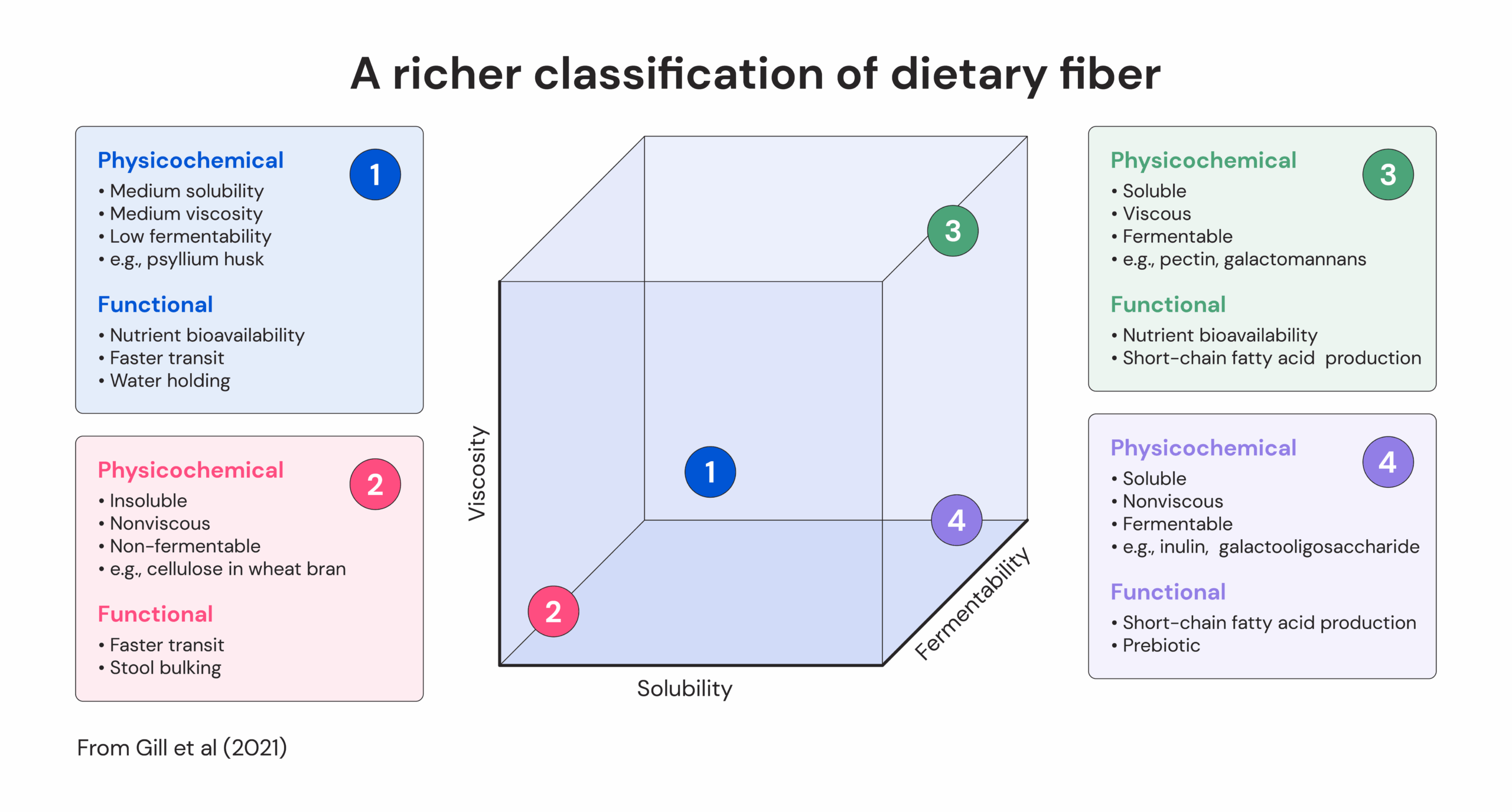

A recent 2025 review pointed out that the most common classifications (soluble versus insoluble) is overly simplistic and doesn’t capture how different fiber types function in the body. Nor do they address that the health effects of fiber depend on characteristics like how well it holds water, whether it ferments slowly or quickly, and how it behaves structurally in your gut. So, it’s fair to say that the research, classifications, and benefits are still evolving.

Gut health, bacteria, and fiber types

For the most part, the things I’m discussing in this article (appetite, glycemic control, cholesterol, regularity, etc.) start with how fiber interacts with your gut microbiota. More specifically, they depend on what type of fiber you’re eating and how it behaves once it reaches your large intestine.

Everyone has a unique gut microbiome, so how your body responds to different fibers will vary. That said, we have a good idea that different fiber types tend to support different microbes.

For example:

- Inulin and pectin can increase levels of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, which are linked to lower levels of gut inflammation.

- Resistant starch fuels Ruminococcus and Bacteroides, which are important for short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production.

- Fructooligosaccharide (FOS) helps boost Bifidobacteria, which is often a sign of healthy gut microbial balance.

In short, if we don’t eat a lot of fiber, we will have less microbial diversity. With decreased diversity, we usually see impaired digestion, inflammation, and a higher chance of metabolic or GI issues. Good bacterial diversity means providing more chances for factors that affect things like fermentation, gut barrier integrity, and other signaling processes.

Therefore, while I’ll get into different fiber specifics (like how viscous fibers slow digestion or how others stimulate the gut lining), the first big lesson to take home is that a diverse fiber intake helps build a more resilient and capable gut microbiota, which sets the stage for a wide range of downstream benefits. With that in mind, I’ll do my best to point out a few useful differences between fiber types without veering into “fiber hacking” territory.

Fiber regarding cardiovascular health and glucose control

When it comes to lowering cholesterol, evidence suggests that certain viscous, gel-forming fibers (like psyllium or oat β-glucan) might be the best fibers due to their effects on bile acid. For a brief background, our liver makes bile acids from cholesterol, and these bile acids make their way to our intestines to aid fat digestion. Most of the time, these bile acids are recycled, but if we ingest certain viscous fibers, they can get trapped in our stool. To compensate, the liver pulls more cholesterol and makes more bile, which can lead to lower circulating cholesterol over time.

Again, only certain types of fiber have this effect. A 2017 study reviewed many fibers that failed to exhibit lowering effects, such as inulin or fructooligosaccharide. However, it found psyllium and oat β-glucan to be the most reactive. An older meta-analysis found that pectin and guar gum (alongside psyllium and oat β-glucan) also had lowering effects.

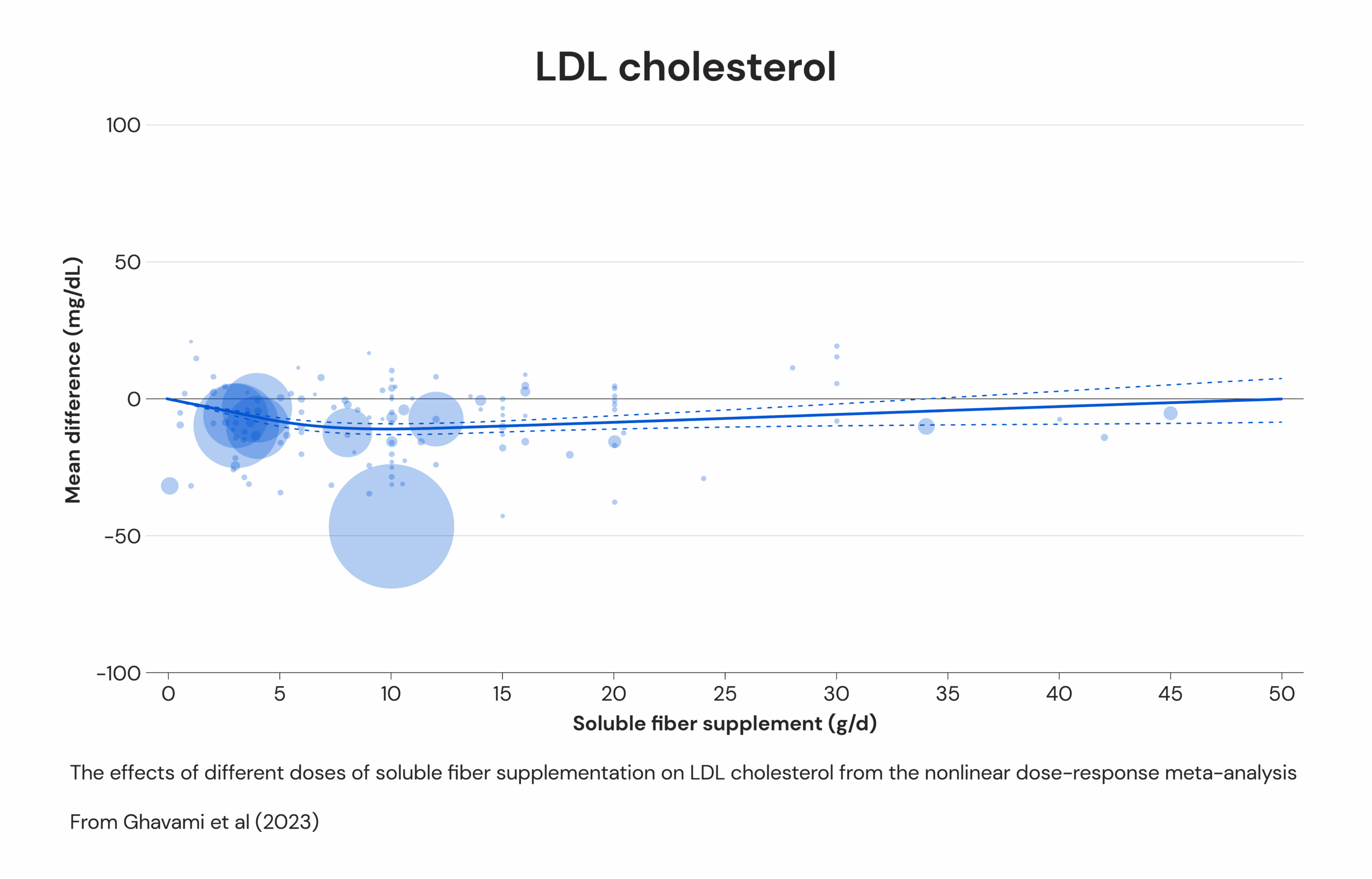

A systematic review and meta-analysis review from Ghavami et al looked at 181 randomized controlled trials with 14,505 participants and wanted to see how different soluble fiber supplementation affects lipid profile. It found that adding more soluble fiber lowered total cholesterol while also reducing other heart health markers. Additionally, it was a dose-response study and noted that not only the type of fiber matters but also that slightly increasing fiber doses improved results. It also noted that nonviscous fibers, like inulin and wheat dextrin, didn’t have much impact.

Moving from cholesterol, we can segue a bit into glycemic control because we are also looking at viscosity as a factor of ideal impact. Once hydrated, viscous fibers (like psyllium, barley, or oat β-glucan) form a gel-like substance that slows how quickly food moves through the digestive tract. This slows the breakdown and absorption of carbohydrates in the small intestine, which then lowers post-eating blood sugar spikes. That slower digestion can also allow more nutrients to reach the lower parts of the intestine, which can help with hormones that decrease appetite (which I’ll get into later).

As with cholesterol, nonviscous or lower viscous fibers seem more hit-and-miss (but not completely ineffective). So, overall it seems you will benefit more from higher viscosity fibers. That said, I want to state that for people with more normal/healthy glycemic control, these fibers won’t have as dramatic of an impact on blood sugar or this effect may be of less concern to you than its effect on appetite. The glycemic control effects will be more noticeable in people with pre-diabetes or type 2 diabetes where there is room for improvement.

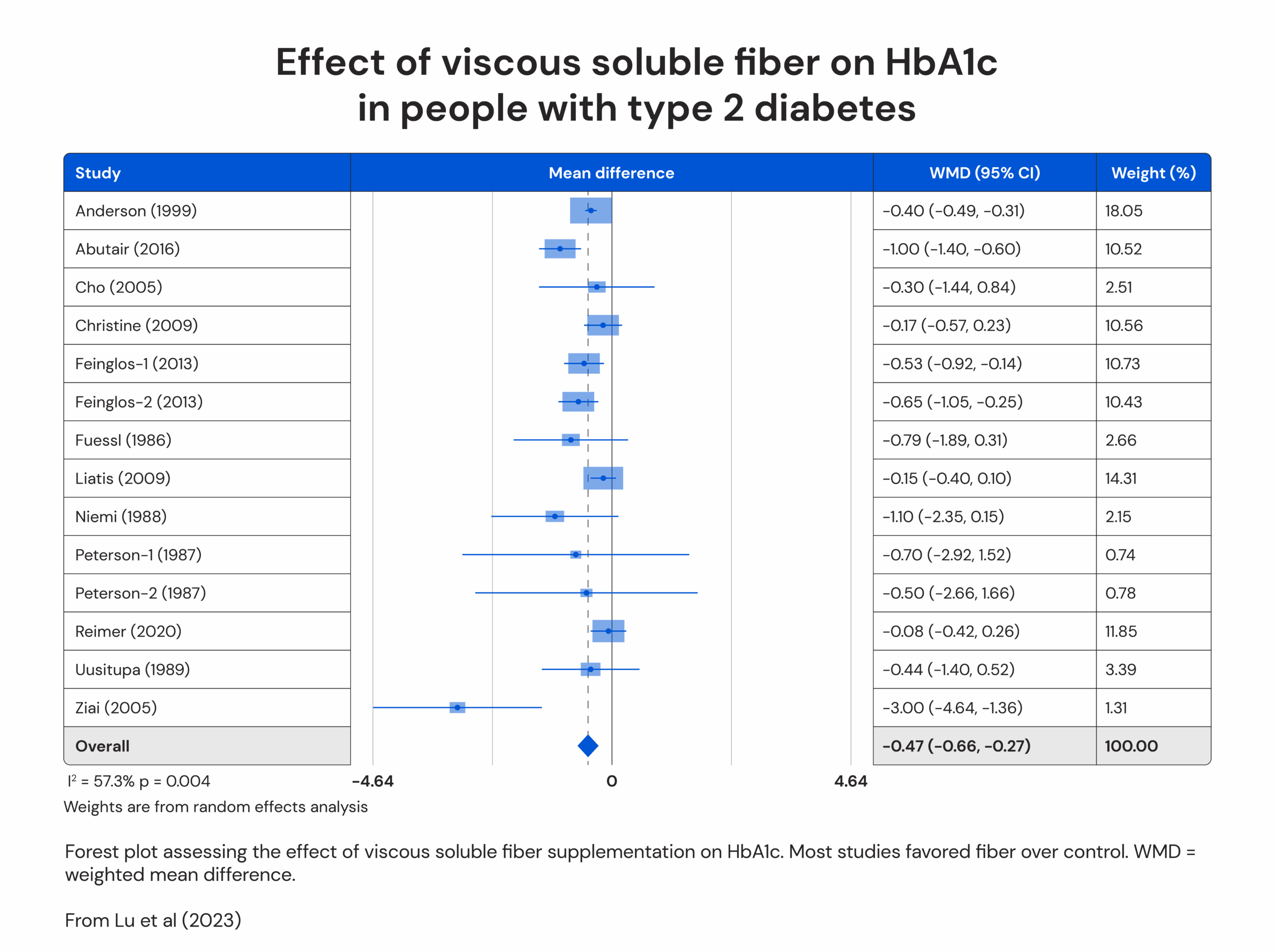

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Lu et al looked at how different viscous soluble fibers (psyllium, guar gum, β-glucan, etc.) affected glucose and lipids in people with type 2 diabetes. They found that adding viscous fibers led to reductions in fasting blood glucose and HbA1c. Interventions longer than six weeks were associated with better outcomes. And while there isn’t a strict threshold, the data suggest that longer durations may yield more benefits.

Short take-home message? If your cholesterol and blood sugar are already in a healthy range, you probably don’t need to stress too much about targeting specific viscous fibers. General satiety strategies will likely get you most of the way there. But if you’re trying to improve your metabolic health, it’s certainly something to talk with the doc about.

How fiber affects appetite and weight regulation

When it comes to weight management (especially if weight loss is the goal), the focus is usually on finding strategies that help increase satiety and reduce energy intake without us feeling constantly deprived. In that context, fiber might help, especially with appetite regulation.

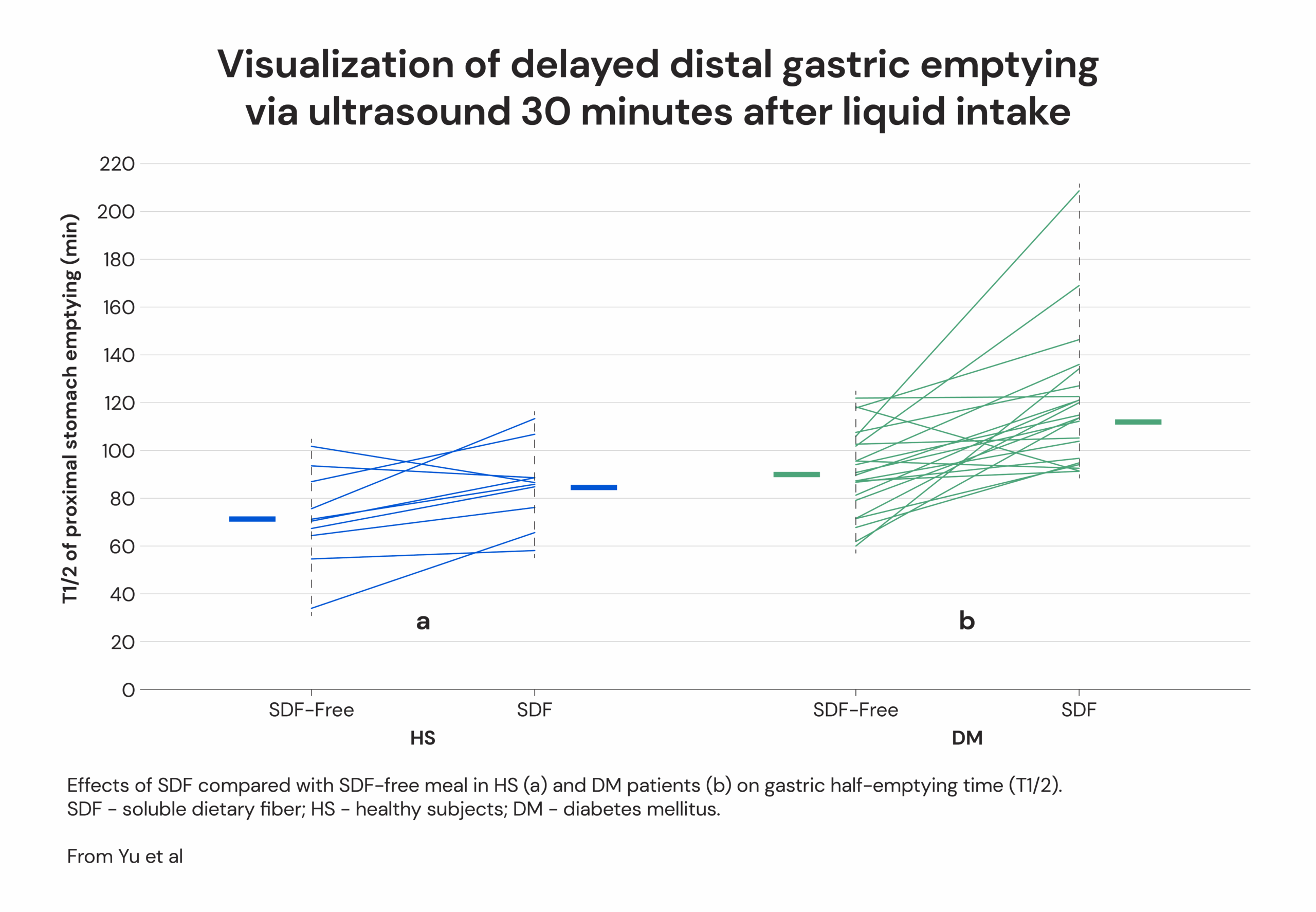

One way fiber could be useful is by slowing down gastric emptying, which is basically how fast food leaves your stomach and enters the small intestine. More viscous fibers hold water, form gels, and sometimes bind to other nutrients, which can slow that process down. Ultimately, that just means food sticks around in your stomach longer, which might help you feel fuller between meals.

A study by Yu et al found notable delays in gastric emptying both in people with type 2 diabetes and in healthy individuals after consuming a soluble fiber drink compared with a fiber-free control. Helping both populations is beneficial because it suggests that this effect isn’t just relevant for people with clinical conditions but that everyone might also see a satiety benefit. A review by Grundy et al also supports the overall benefit, though they note that not all fibers behave the same.

Another possible appetite-related mechanism is the stimulation of satiety hormones like GLP-1 and PYY. When food moves more slowly through the gut, it increases the opportunity for these hormones to be released, potentially enhancing the feeling of fullness after a meal. That said, an increase in satiety hormones doesn’t guarantee someone will actually feel more full. As covered in our satiety article, what fullness or satiety is to one person can be very different from another and, at times, tricky to study. Fiber type, dosage, whole meal compositions, and even how someone personally defines or reports “feeling full” can complicate things.

Still, there’s a decent body of evidence showing that fiber (especially viscous soluble fiber) can support appetite regulation. And this can all lead to better weight regulation, even if you’re not trying to actively lose weight. For instance, a systematic review and meta-analysis from Huwiler et al tested whether supplementing with isolated soluble fibers could affect body weight and other metabolic markers without a purposeful Calorie restriction. The results showed that even though participants weren’t actively trying to decrease Calories, they saw small reductions in body weight and BMI. This was also similar to a review by Jovanovski et al a few years before.

Short take-home? Unlike the previous section, where benefits were mostly limited to those with clinical markers to improve, fiber intake (especially soluble, viscous types) may help with appetite and weight management even in generally healthy individuals.

Fiber intake and regularity

This is probably the part you expected when you clicked on an article about fiber. Regularity mostly comes down to two things: how often you go and what the stool looks like when you do. Frequency matters, but most people are more concerned with consistency of the stool. Ideally, you want something well formed and easy to pass. If stools are too loose or fall apart, that’s leaning toward diarrhea. If they’re hard, dry, or come out in small pieces, that’s leaning toward constipation.

We haven’t talked much about insoluble fiber yet, but it tends to come up more in the context of regularity. Insoluble fibers mostly do two things: they add bulk to stool by increasing its physical mass, and they mechanically stimulate the gut lining, which can boost mucosa secretion and movement. What they don’t do is hold water. So, if the goal is softer, easier-to-pass stools, you also need soluble fibers (especially the gel-forming kind but not so much fermentation) that help retain water and hold everything together. The combination of bulk from insoluble fiber and water retention from soluble fiber can come together to make for softer (but solid) stools.

| Fiber type, fermentation, and effects on stool consistency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiber type | Main action in the large bowel | Holds water? | Resists fermentation? | Effectiveness for softer stools? |

| Coarse insoluble fiber | Mechanically irritates bowel lining and triggers secretion | No | Yes | Yes, if coarse (e.g., wheat bran) |

| Gel-forming soluble fiber | Retains water to resist dehydration of stool | Yes | Yes | Yes (e.g., psyllium) |

| Soluble fermentable fiber | Rapidly fermented, doesn’t usually reach distal bowel intact | No | No | No |

| Finely ground insoluble | Adds dry mass without holding water | No | Yes | May worsen constipation |

| Table inspired by McRorie and McKeown (2017) McRorie and McKeown | ||||

I should also note that water plays an important role here, and it’s often overlooked in fiber conversations. When the table above mentions whether a fiber “holds water,” that water has to come from either the fluid content of foods like fruits and vegetables or from what you drink. Without enough water, even the right fiber combination won’t work as well, and you might actually make things worse.

This is also setting aside more complicated digestive conditions, which I’m not covering here. For most healthy people, a little fiber variety goes a long way. You could make the case that regularity is possible without insoluble fiber, but much more difficult without the right kind of soluble fiber. Specifically, you’ll need mostly non-fermentable, gel-forming types if the goal is consistent, manageable stools (psyllium is the usual go-to for a reason). That said, the best long-term approach is still getting there through a varied whole-food diet, and let’s not forget all the yummy micronutrients that come along with it.

Short take home? For generally healthy individuals, regularity doesn’t require anything fancy, just a little extra focus on gel-forming soluble types (and plenty of water to help it all work).

Fiber intake and practical considerations

The WHO suggests that adults aim for 25-30 grams daily, while the USDA recommends 14 grams per 1,000 Calories. So if you’re eating 2,000 Calories daily, that would mean around 28 grams of fiber. More recent data shows that average fiber intake among Europeans falls short of recommendations and that the average fiber intake among American adults is just 16 g/day. So, in general there’s certainly an issue with getting more adequate fiber intake and a need to be mindful and proactive.

You’ve probably noticed that many of the more impressive results in fiber research come from studies using isolated viscous fiber supplements. That’s mostly a design issue because it’s much easier to study a specific dose of something like psyllium than to control for the variety and quantity of fiber in a mixed whole-food diet. Some studies have also pointed out that the effects seen with supplements don’t always translate to fiber from fruits or vegetables alone. So from a research standpoint, supplements make things clearer but from a real-world perspective, it can be a bit more complicated.

In the real world, while you can use supplement sources, more than likely (hopefully), you’ll get most of your fiber from fruits, vegetables, pulses, and seeds. Some research has shown improvements in gut microbiota even after just two weeks of increasing whole-food fiber intake. That said, the specific types and sources of fiber that work best can vary. For some people, a small amount of supplemental fiber makes a big difference; for others, it may not be necessary at all.

| Whole food sources of dietary fiber | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Food | Total fiber (g/100g) | Insoluble fiber (g/100g) | Soluble fiber (g/100g) |

| Barley | 17.3 | ‒ | ‒ |

| Corn | 13.4 | ‒ | ‒ |

| Oats | 10.3 | 6.5 | 3.8 |

| Wheat (whole grain) | 12.6 | 10.2 | 2.3 |

| Wheat germ | 14 | 12.9 | 1.1 |

| Kidney beans (canned) | 6.3 | 4.7 | 1.6 |

| Lentils (raw) | 11.4 | 10.3 | 1.1 |

| White beans (raw) | 17.7 | 13.4 | 4.3 |

| Beetroot | 7.8 | 5.4 | 2.4 |

| Spinach (raw) | 2.6 | 2.1 | 0.5 |

| Bananas | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.5 |

| Almonds | 11.2 | 10.1 | 1.1 |

| Flaxseed | 22.3 | 10.2 | 12.2 |

| Green beans | 1.9 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| Peas (green, frozen) | 3.5 | 3.2 | 0.3 |

| Lima beans (canned) | 4.2 | 3.8 | 0.4 |

| Eggplant | 6.6 | 5.3 | 1.3 |

| Carrot (raw) | 2.5 | 2.3 | 0.2 |

| Broccoli (raw) | 3.29 | 3 | 0.29 |

| Apple (unpeeled) | 2 | 1.8 | 0.2 |

| Kiwi | 3.39 | 2.61 | 0.8 |

| Strawberry | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| Pear | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Coconut (raw) | 9 | 8.5 | 0.5 |

| Peanut (dry roasted) | 8 | 7.5 | 0.5 |

| Cashew (oil roasted) | 6 | ‒ | ‒ |

| Sesame seed | 7.8 | 5.9 | 1.9 |

| Artichokes | 5.7 | ‒ | ‒ |

| Avocado | 6.7 | 1.7 | 3.9 |

| Blackberries | 5.3 | ‒ | 2.8 |

| Raspberries | 6.4 | ‒ | 3.0 |

| Table mostly comes from Dhingra et al (2011) | |||

| Common supplement sources of dietary fiber | |

|---|---|

| Supplement | Type |

| Psyllium husk | Soluble, gel-forming |

| Guar gum | Soluble, gel-forming |

| Inulin | Soluble, fermentable |

| Wheat dextrin | Soluble, nonviscous |

As with most things in nutrition, some self-experimentation is usually the best approach. Hopefully, by now, you have a clearer idea of what to look for and where fiber might help most in your situation.

One more consideration when it comes to fiber sources is processing methods and your intended use. For example, a study on cereal β-glucan found that different processing methods can affect its viscosity. That matters, since viscosity is a key factor in how well these fibers help lower cholesterol. Similar findings have been reported in baked goods, so depending on your goal, it’s worth paying attention to how a fiber-containing product was made.

And finally, a common issue with fiber is trying to add too much too quickly. If you’ve been eating a low-fiber diet, it might be better to increase gradually rather than making a big jump all at once. For many people, there’s an initial adjustment period, and easing into a higher-fiber intake can help minimize the digestive discomfort.

Short take home? On average, most people are probably not getting enough fiber. Ideally, try to get it from whole foods as much as possible but if you are going to use fiber supplements, it’s probably best to use fibers that you add to room temperature water versus higher quantities of fiber food “products” if looking for ideal and “bang-for buck” gut benefits.

Take home

Believe it or not, we didn’t dive into everything fiber intake can help with or affect positively (here, here, here, and here). I could have certainly made a fiber series, but hopefully I’ve made a good case for paying more attention to your fiber intake. To keep it simple, here are some basics:

- Fiber isn’t just one thing. Different types of fiber do different jobs.

- Not all fibers have the same benefits. That’s why it helps to eat a mix of fiber types.

- Viscous fibers — like psyllium or oat β-glucan — seem especially helpful for blood sugar, cholesterol, and weight management.

- Insoluble fiber helps with regularity but works best when paired with gel-forming soluble fiber.

- Getting fiber from whole foods like fruits, vegetables, pulses, and seeds is a great place to start. That said, if whole-food sources are limited, some people may benefit from supplements.

- If you’re increasing fiber, add it slowly and drink more water, this helps with possible negative side effects.

- You don’t need to overthink fiber. Just aim for variety and consistency. Most benefits come from regular intake over time.