Table of contents

- Understanding the digestion and distribution of protein

- Amino acid profiles

- What do we mean when we talk about protein quality?

- Does cooking denature proteins?

- Are there any cooking styles that harm amino acid bioavailability?

- Applying all of this to a daily diet for most people

- What about vegetarians and vegans?

- Practical application of tracking complementary proteins

In this article, we explore methods of rating protein quality and the effects of meal preparation methods on protein. For some populations, we also examine the need to closely monitor amino acid variety in their daily diet. Lastly, practical applications are provided for vegans to ensure they obtain adequate protein sources.

Let’s dig in!

Understanding the digestion and distribution of protein

To understand how to rate protein quality, you need a short primer on how you digest protein.

All proteins are constructed from individual building blocks called amino acids. When consumed, proteins are typically in a folded structure. As you digest protein in your stomach, gastric fluids start to help the structures unfold. Enzymes such as Pepsin continue to break these structures down into smaller peptides (shorter chains of amino acids). This dismantling process is completed in the small intestine, where enzymes like trypsin and chymotrypsin further break down the peptides into free amino acids.

These amino acids are eventually absorbed into the bloodstream and contribute to the body’s amino acid pools. Ultimately, the goal of digestion is to break down proteins into their individual components.

Amino acid pools are distributed throughout the body in various compartments such as blood plasma, intracellular fluid, and extracellular fluid. Cells draw from these pools for repair, growth, and other metabolic processes. Amino acids are available throughout the body and ready to respond to injury, increased demand, or building requirements. It’s all pretty spectacular.

I should note that this article focuses on protein and amino acids, but protein utilization takes place in the context of a mixed diet (including carbohydrates and fats). Protein synthesis for muscle building is influenced by carb intake, because insulin can play a role. For cell membrane construction, you also need fats. Thus, a mixed diet is essential and relevant. However, for this article, I am focusing on protein.

Amino acid profiles

The human body requires 20 amino acids to function. Each amino acid has its own role in biological functionality and all amino acids are categorized into three groups: essential, non-essential, and conditionally essential.

| Amino acid type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Essential amino acids | These amino acids, which the human body cannot synthesize, must be obtained through diet. | Histidine, Isoleucine, Leucine, Lysine, Methionine, Phenylalanine, Threonine, Tryptophan, Valine |

| Non-essential amino acids | Amino acids that the body can produce on its own and usually do not depend on dietary intake. | Alanine, Asparagine, Aspartic acid, Glutamic acid, Serine |

| Conditionally essential amino acids | Some health conditions and illnesses may require the dietary intake of these amino acids. The specific needs can vary depending on age, the nature of the illness, and other variables. | Arginine, Cysteine, Glutamine, Glycine, Proline, Tyrosine |

It’s also common in research to see essential amino acids referred to as “indispensable” and non-essential amino acids referred to as “dispensable.”

Essential amino acids have to be obtained from your diet. Conditionally essential amino acids are usually non-essential, but they can become essential under specific conditions, such as stress, illness, or rapid growth spurts. Non-essential amino acids are amino acids that your body can make on its own, meaning you don’t necessarily need to ingest them in your diet.

A quick point I feel compelled to highlight: While the body must obtain nine essential amino acids through the diet, it doesn’t mean diet isn’t important for the other eleven. Non-essential amino acids are considered non-essential because your body can synthesize them from the backbones of other amino acids, so your total intake of amino acids (i.e. your total protein intake) is still relevant. Yes, eating food that provides essential amino acids will usually ensure you’re getting the other eleven, but just because the body can synthesize non-essential amino acids, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t support it with adequate total protein intake. Only hitting the nine essential amino acids and no other protein would not provide the body with sufficient protein nutrition.

Essential amino acid daily requirements for a 70-kg adult

| Amino acid | RDA (mg/kg/day) | Daily requirement (mg) for 70-kg adult | Daily requirement (g) for 70-kg adult |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histidine | 14 | 980 | 0.98 |

| Isoleucine | 19 | 1,330 | 1.33 |

| Leucine | 42 | 2,940 | 2.94 |

| Lysine | 38 | 2,660 | 2.66 |

| Methionine | 19 | 1,330 | 1.33 |

| Phenylalanine | 33 | 2,310 | 2.31 |

| Threonine | 20 | 1,400 | 1.40 |

| Tryptophan | 5 | 350 | 0.35 |

| Valine | 24 | 1,680 | 1.68 |

From Trumbo et al (2002)

Hopefully, you understand you need to have a collection of all amino acids ready and available to service your body at all times. Now the question is, “How do we know if what we are eating is doing that job? How do we know the protein we are eating is quality protein?”

What do we mean when we talk about protein quality?

When discussing protein quality, let’s focus on two key questions:

- Can your body digest and absorb the protein?

- Can your body use the protein effectively once it’s absorbed?

Digestion and absorption

For a protein to be considered a high-quality protein, your body needs to be able to break it down, digest it, and absorb its amino acids. Your body’s enzymes and digestive proteins are really good at unraveling most protein structures and splitting up most amino acid sequences, but certain protein structures and amino acid sequences are a bit more of a challenge.

Furthermore, some cooking or processing techniques (discussed more below) can affect the structure of a protein, making it either a bit easier or a bit harder to digest. So, high-quality proteins are proteins that are easier for your body to digest, such that you’re able to break down and absorb the vast majority of the amino acids in the protein. This is mostly influenced by the protein’s structure but it can also be affected by how the protein is cooked or processed.

Effective utilization

Once a protein is digested and absorbed, your body needs to be able to use it. This mostly boils down to the amino acid composition of the protein: does it have sufficient amounts of the essential amino acids? For instance, if you can digest and absorb all of the amino acids in a protein, but the protein completely lacks lysine, your body won’t be able to use the rest of the amino acids as effectively. Most proteins in your body include at least a few lysine molecules, so the lack of lysine severely hampers your body’s ability to make use of the rest of the amino acids. If, on the other hand, the protein does have sufficient levels of all of the essential amino acids, there’s nothing limiting your body’s ability to make good use of all of the amino acids you absorbed.

So, for a protein to be considered a high-quality protein, it needs to be easy to digest and absorb, and it needs to have an amino acid composition that ensures your body will be able to fully utilize it. If a protein is easily digested but it lacks essential amino acids or has low levels of essential amino acid, it can’t be considered high-quality. Conversely, if a protein has an excellent amino acid profile but it is hard to digest, it’s also not high-quality.

Assessing protein quality via PDCAAS and DIAAS

There are two main scoring systems to assess protein quality:

- Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS):

- PDCAAS compares the amino acid profile of a protein to a reference profile and adjusts for digestibility using fecal analysis.

- The amount of undigested nitrogen and amino acids in fecal matter indicates what wasn’t utilized by the body.

- One limitation is that microbial fermentation in the large intestine can falsely elevate digestibility values. Additionally, PDCAAS caps at 1.0, meaning it can’t differentiate proteins that exceed essential amino acid requirements.

- Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS):

- DIAAS measures absorption at the end of the small intestine (ileum) before reaching the large intestine.

- This method can yield scores above 100%, allowing differentiation of superior proteins.

- DIAAS can be more costly and more invasive, often requiring studies on animals like pigs or rats. It’s noted that pigs are preferred for human comparison.

- DIAAS can also have limitations, but it is currently considered better than the previous scoring system.

Quality of protein by source and PDCAAS & DIAAS scores

| Food | PDCAAS | DIAAS |

|---|---|---|

| Whole milk | 1.00 | 1.43 |

| Chicken breast | 1.00 | 1.08 |

| Whey protein isolate | 1.00 | 1.09 |

| Milk protein concentrate | 1.00 | 1.18 |

| Egg | 1.00 | 1.13 |

| Beef | 1.00 | 1.116 |

| Potato | 1.00 | 0.85 |

| Soy protein isolate | 0.98 | 0.90 |

| Pea protein concentrate | 0.89 | 0.82 |

| Lentils | 0.80 | 0.75 |

| Tofu | 0.70 | 0.97 |

| Chickpeas | 0.52 | 0.67 |

Testing for utilization

Testing for amino acid utilization can be tricky and costly. Currently, stable isotope testing is becoming the popular method of testing. Researchers label amino acids with non-radioactive stable isotopes that act as tracers to see where amino acids go and how they are used in the body. However, there are limitations on how long these tracers can be followed, and it often requires invasive and repeated biopsies to get the whole picture.

The biggest takeaway from all of this is just that “protein quality” describes how effectively your body can digest and utilize a particular protein. You don’t need to be too concerned with the differences between the various scoring systems, because they tend to track with each other quite well, and they paint similar pictures overall. In both cases, a higher score is better. Scores closer to (or exceeding) 1 are indicative of very high-quality proteins. Scores above ~0.7 are indicative of pretty good-quality proteins. Scores below 0.5 are indicative of low-quality proteins.

Key additional points

- Almost all animal proteins (except collagen) are high-quality. This is particularly relevant for vegans who need to be more mindful of protein quality.

- PDCAAS and DIAAS are most critical in contexts addressing malnutrition or global nutritional needs but are less vital in a balanced diet with adequate-to-high protein intake.

- Ultimately, methods like DIAAS and PDCAAS assess protein digestibility, while newer techniques, such as dual stable isotope tracing, examine amino acid utilization. These methods aren’t perfect, so it’s important to consider total protein intake first. For those following a vegan diet, focus on the amino acid profiles to ensure adequate intake of all essential amino acids.

Does cooking denature proteins?

The inner workings of the digestive system are quite specific. Acid levels and enzyme activity are calibrated to help unfold proteins and bind substrates for utilization.

A question often raised is whether cooking denatures protein. In research, there can be overlap in the conversation and terminology about denaturing, deamination, and degradation (to name a few) which can lead to confusion about their impact on bioavailability.

Denaturing, which refers to changing the fold of a protein, doesn’t always harm bioavailability. In fact, it can sometimes enhance the absorption or cleaving of amino acids. However, in some cases, it can reduce the actual bioavailability of the amino acids. Ultimately, the impact depends on the context and the reference.

Are there any cooking styles that harm amino acid bioavailability?

A few things we do in the kitchen or how we combine food items can lead to a slight decrease in bioavailability. I’ll start by saying that most of these have minimal overall impact. However, you might want to reconsider your cooking style if you burn everything you eat or you have a penchant for chomping on raw legumes. Lastly, this section highlights some but not all factors that affect amino acid digestion or bioavailability.

Maillard reaction

You probably recognize the Maillard reaction in your kitchen from browned toast, grilled seared meat, or dark roasted coffee beans. These are all expressions of the Maillard reaction, often called the “browning” effect on food.

The Maillard reaction is a nonenzymatic browning reaction that involves altering a protein’s chain by attaching a sugar. This process changes the structure of the amino acids, which is different from just “unfolding it.” During digestion, when proteins are cleaved and broken down into smaller bits, some of these altered amino acids are no longer recognized by our digestive enzymes due to the binding during the Maillard reaction. This can affect their digestion during the enzymatic stage.

The fate of these undigested amino acids can be further complicated by gut fermentation, where gut bacteria can metabolize some into byproducts.

With all that said, if just the edge of your food is browned, it’s likely to have a negligible effect. Just avoid eating overly charred steak and blackened toast. The total browned surface area also matters. If you put a hard sear on a steak, most of the total mass of the steak hasn’t experienced the Maillard reaction. However, if you deeply browned an equivalent amount of hamburger meat, more total surface area will undergo Maillard browning, and more of the total protein will be negatively impacted.

Anti-nutrients

There is some concern that a percentage of amino acids can’t be absorbed in the presence of anti-nutritional factors. For instance, trypsin inhibitors can interfere with the activity of trypsin – an enzyme essential for protein digestion. If the enzyme can’t interact properly during various digestion stages, some peptides may not be fully broken down and digested.

Tannins create a similar concern by binding to proteins and amino acids, forming complexes that are difficult for digestive enzymes to break down. Lectins, phytic acid, and even fiber also pose issues since they can interfere with enzymes getting to the amino acids in the food, preventing enzymatic activity from properly breaking them down.

It is important to understand the degree and validity of each of these anti-nutrients, but the good news is that most common food prep methods can eliminate many of these issues and usually enhance the culinary experience.

What about boiling or raw?

Boiling your food or not cooking it at all can also affect it.

Ito et al found boiling reduced the free amino acid content in vegetables, though some vegetables like snap peas and spinach retained more amino acids than others like carrots and cabbage. On the positive side, the amino acids leach out into the liquid, so this is not much of an issue if you’re making a soup. Specifically, asparagine (Asn), glutamine (Gln), and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) were among the most affected amino acids and showed the largest reductions after boiling.

In a study by Fuchs et al, ingestion of boiled eggs led to a 20% higher peak in plasma essential amino acid (EAA) concentrations compared to raw eggs. Despite this, there was no significant difference in post-exercise muscle protein synthesis rates between raw and boiled eggs. This suggests that while cooked eggs are more digestible, both forms of eggs similarly support muscle protein synthesis after exercise.

Looking at the effects of cooking on meat and seafood, Bhat et al suggests that while moderate cooking temperatures (around 70°C) may enhance the digestibility of some meat proteins, higher temperatures (above 100°C) generally reduce protein digestibility due to structural modifications and oxidation.

Cooking take home?

Food preparation methods probably won’t have a huge impact on protein quality unless you’re participating in some pretty intensive charring, tossing your soup liquids, or eating all of your eggs raw. Additionally, how you prepare or cook your food overall could lead to gains that make up for the loss. With that said, it never hurts to follow general cooking safety guidelines.

General cooking guidelines

| Product | Minimum Internal Temperature & Rest Time |

|---|---|

| Beef, pork, veal & lamb steaks, chops, roasts | 145 °F (62.8 °C) and allow to rest for at least 3 minutes |

| Ground meats | 160 °F (71.1 °C) |

| Ground poultry | 165 °F |

| Ham, fresh or smoked (uncooked) | 145 °F (62.8 °C) and allow to rest for at least 3 minutes |

| Fully cooked ham (to reheat) | Reheat cooked hams packaged in USDA-inspected plants to 140 °F (60 °C) and all others to 165 °F (73.9 °C). |

| All poultry (breasts, whole bird, legs, thighs, wings, ground poultry, giblets, and stuffing) | 165 °F (73.9 °C) |

| Eggs | 160 °F (71.1 °C) |

| Fish & shellfish | 145 °F (62.8 °C) |

| Leftovers | 165 °F (73.9 °C) |

| Casseroles | 165 °F (73.9 °C) |

Source: USDA

Applying all of this to a daily diet for most people

With all this talk about digestibility, cooking your eggs, or the hopes of dual stable isotope research, I think the easiest way for the average person to navigate protein intake is to focus on their overall intake of amino acids. The FAO report states, “Use of estimates of the amounts of individual digestible amino acids in a protein is likely to be the most successful approach to determining the optimal protein, or combinations of proteins, to be used in any circumstance.”

Basically, are you meeting your total daily protein intake needs and taking a special interest in covering your essential amino acids?

If that seems overwhelming, it’s not. In fact, if you’re an omnivore, pescatarian, or a vegetarian who eats eggs, dairy products, and/or bivalve mollusks, you only need to focus on your overall protein intake. Even if you’re not concerned with how you cook your meats, or you decide to chug down a raw egg, you should be fine as long as you’re getting your total daily intake and including animal protein.

It may be worth noting that you don’t need to exclusively consume high-quality proteins, or only “count” high-quality proteins, since protein intake recommendations come from research where subjects would be consuming between 1/3 and 2/3rds of their total protein intake from lower-quality sources. For more detailed recommendations, this article discusses how much protein you can eat daily for different populations.

What about vegetarians and vegans?

Because there are different types and levels of vegetarians, let’s start off with common definitions.

Levels of vegan and vegetarians

| Type | Includes | Excludes |

|---|---|---|

| Vegan | Fruits, vegetables, grains, nuts, seeds, legumes | All animal products (meat, poultry, fish, dairy, eggs, honey) |

| Lacto-vegetarian | Dairy products (milk, cheese, yogurt), plant-based foods | Meat, poultry, fish, eggs |

| Ovo-vegetarian | Eggs, plant-based foods | Meat, poultry, fish, dairy products |

| Lacto-ovo-vegetarian | Dairy products, eggs, plant-based foods | Meat, poultry, fish |

| Pescatarian | Fish, seafood, plant-based foods | Meat, poultry |

| Flexitarian | Primarily plant-based foods, occasional meat and animal products | No strict exclusions, but minimal meat consumption |

For transparency, I’m currently a lacto-ovo-vegetarian who participates in alternating vegan days. I started being a vegetarian at 15 but had periods where I was not. I’ve been a lacto-ovo-vegetarian for well over 12 years and have been vegan for periods. I recognize the limitations and difficulties these diets present for training enthusiasts and those who choose a vegan diet for religious, ethical, or political reasons.

If you’re a meat eater or a vegetarian who includes any level of animal products, getting all 9 essential amino acids is not difficult. Milk or egg protein has complete amino acid profiles. So, even if you’re not eating meat, combining those proteins with vegetables, grains, and legumes is typically more than enough to meet amino acid needs. It is a little more complicated when you exclude all animal products because you may not get an adequate amount of all 9 essential amino acids.

Why is getting all 9 essential amino acids important?

An important aspect of protein’s mechanistic properties is that essential processes cease functioning if we don’t get what we need. For example, suppose you’re vegan and don’t get enough lysine. In that case, you’re missing a precursor for L-carnitine, crucial for transporting fatty acids into the mitochondria (the “powerhouse of the cell”). Without adequate lysine, you won’t produce enough L-carnitine, leading to low energy, fatigue, and poor recovery, among other issues. This is also discussed in the context of limiting proteins.

It’s important to note that synthesizing L-carnitine involves methionine and other vitamins. This isn’t a solo act; everything plays a role. The lack of certain nutrients can be more problematic than others due to our body’s ability to more easily synthesize some compounds over others, highlighting the essential versus non-essential nutrient distinction.

Do vegans need to worry about getting their 9 essential amino acids?

Maybe. It depends on the kind of vegan they are and the variety of amino acids they get. It’s why, if you’re taking part in a restrictive diet that excludes animal proteins, you should probably pay attention to your amino acids. When it comes to lifting and building muscle, a few recent studies here and here have shown that as long as protein intake is high enough, plant protein does the job regarding protein synthesis.

It’s worth noting that there are complete vegan proteins (most notably soy/tofu, but also quinoa, buckwheat, and many mushrooms), and many vegan athletes use supplements with complete proteins (either soy, or a pea/rice blend). So, if that applies, you probably don’t need to worry about most of this stuff. But, if you’re a vegan who doesn’t use supplements and eschews soy, you may need to pay more attention to complementary proteins.

A fair debate that’s often raised is whether the RDA recommendation for protein at 0.8g/kg of body weight for a mixed diet is valid for the general population, let alone for vegans. I think there’s an argument that the “general population” guidelines don’t entirely ensure adequate protein for vegans. This is based on the logic that whole food protein sources usually come with a carbohydrate or fat companion. Unless vegans get a bigger portion of protein from protein powders, aiming for a slightly higher overall daily protein intake (1.2-2.2g/kg body mass per day, approximately 0.55-1.0g/lb) seems to be the ideal safeguard.

How to set up and monitor complementary protein intake for vegans

Utilizing complementary protein sources is only necessary for vegans. There’s no need to make this kind of chart for animal-based protein sources. However, if you’re a vegan, this can be a way to ensure you’re covering your nutritional bases.

Below, I’ve listed the primary protein source. In the next column, the often missing or trace amount of amino acid that is missing is used to make that protein source full of all nine essential amino acids. The final right column provides examples of complementary sources you can use that are higher in that missing amino acid.

Complementary protein table

| Protein source | Low or missing amino acid(s) | Complement source(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Complete proteins | ||

| Soy | None | No complement needed |

| Quinoa | None | No complement needed |

| Buckwheat | None | No complement needed |

| Mushrooms (some) | None | No complement needed |

| Grains | ||

| Wheat | Lysine | Black beans, lentils |

| Rice | Lysine | Pea, lentils |

| Oats | Lysine | Soy, black beans |

| Legumes | ||

| Pea | Methionine, Cysteine | Rice, wheat |

| Lentils | Methionine, Cysteine | Rice, oats |

| Black Beans | Methionine, Cysteine | Quinoa, wheat |

| Nuts and seeds | ||

| Pumpkin Seeds | Methionine, Cysteine | Lentils, wheat |

| Almonds | Methionine, Lysine | Lentils, black beans |

| Sunflower Seeds | Methionine, Lysine | Quinoa, black beans |

| Leafy greens | ||

| Kale | Methionine, Lysine | Lentils, wheat |

| Spinach | Methionine, Lysine | Lentils, wheat |

From Wolff et al (2011)

Practical application of tracking complementary proteins

On days when I do not have any animal products, I use my tracking app to optimize my amino acid profile. For this example, I will use the MacroFactor app, but you can use whatever app you want.

To get the most accurate amino acid breakdowns, it’s recommended to log foods exclusively from the “common foods” section in your tracking app. This ensures you have access to the complete micronutrient and amino acid information. MacroFactor, for example, has a large, verified common food search database of 26,500 micronutrient-rich, research-grade food entries. You can find detailed instructions on how to log these foods here.

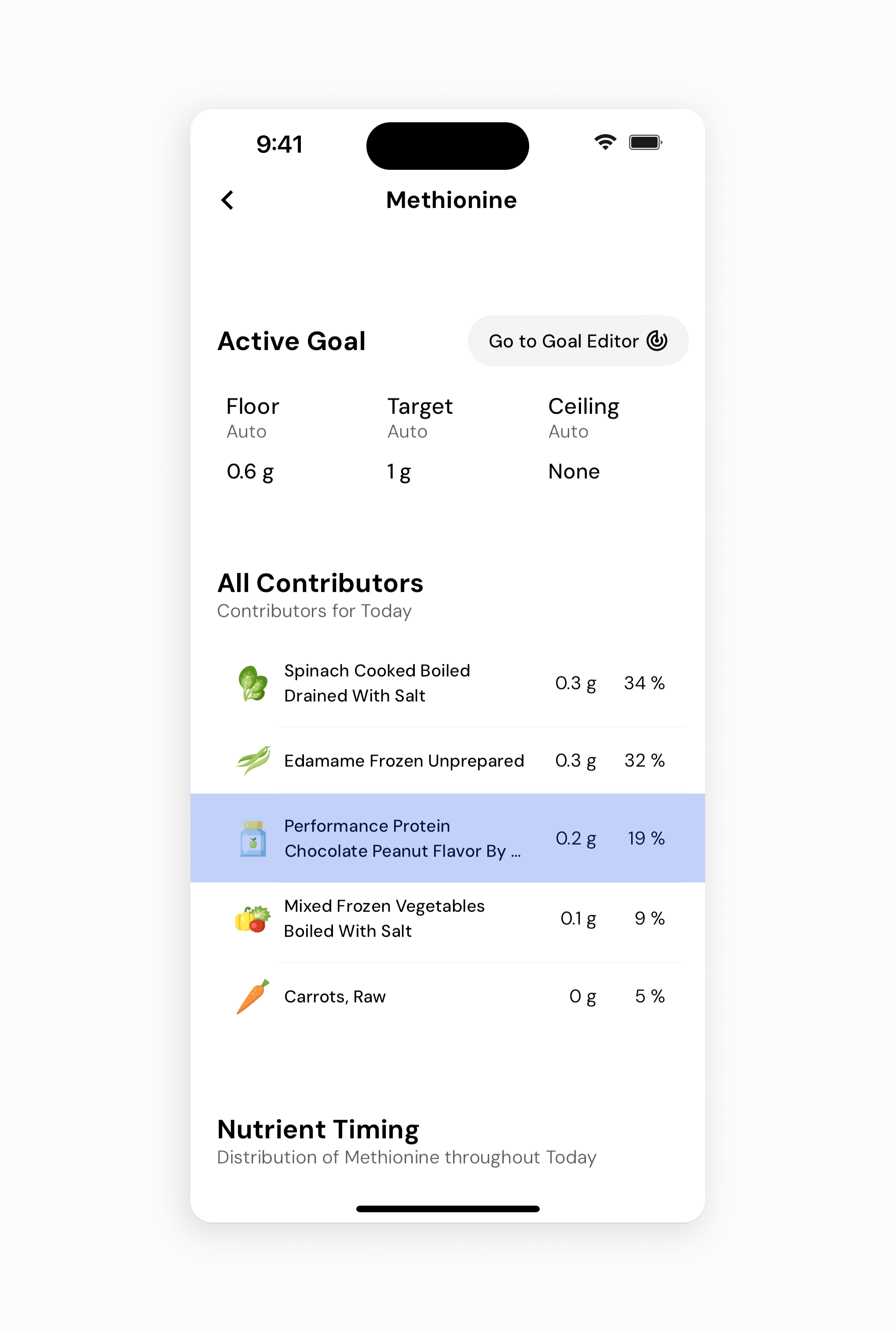

In this example, you can see that I’ve almost hit all my amino acids, but I’m still a little low on methionine.

For the record, methionine is a commonly low amino acid for vegans. I also want to point out that there may be sources not accounted for in my diet this day. However, if you want to be overly cautious and ensure 100% of all amino acids, you can look at the top contributors of your diet for methionine and see if you can increase your daily intake. I see I’m getting a decent amount via my protein powder of mixed protein sources. In this case, it’s easy enough to just double up my scoop amount.

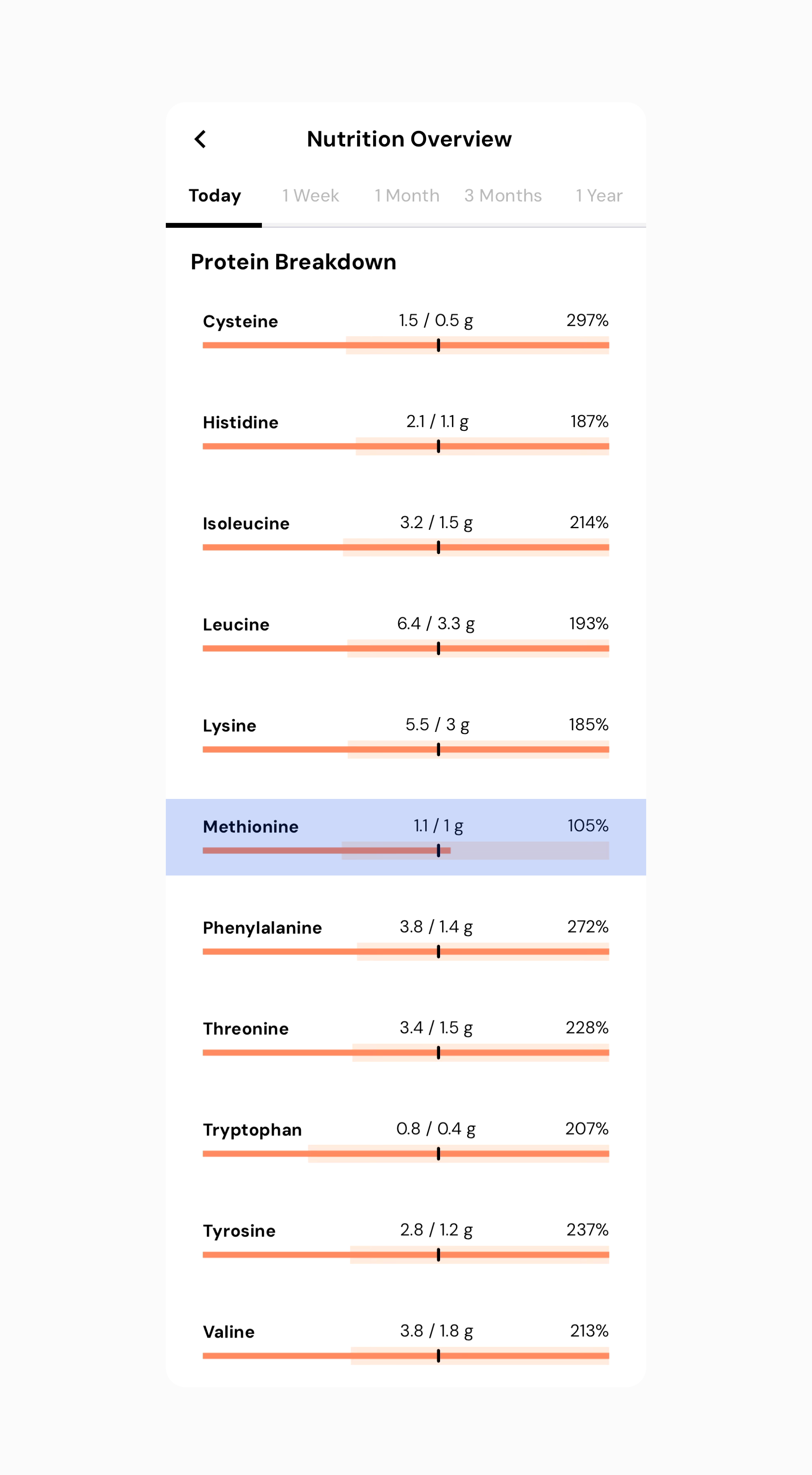

After increasing my serving size, I’m now hitting 100% or more of all my essential amino acids.

This example illustrates that if you’re a vegan and concerned about meeting your amino acid targets, you can organize your food intake to maximize nutrition. If combining different complementary foods is challenging with whole foods alone, many people use a vegan protein mix to cover their amino acid needs without analyzing it in such detail.

.