Featured Research

Macroeconomic Insights: South Africa CPI – When Currency Strength Meets Energy Vulnerability

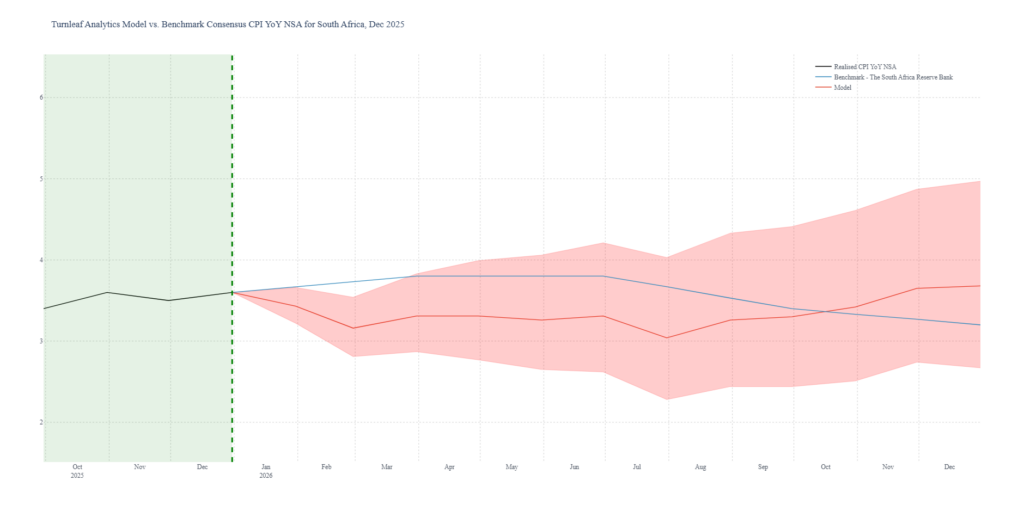

After trending downward through most of 2025 alongside rand appreciation and falling oil prices, Turnleaf’s 12 month inflation forecast for South Africa is now pointing at rising inflation pressure in 2026 (Figure 1). Rebounding oil prices are overwhelming the...

Macroeconomic Insights: South Africa CPI – When Currency Strength Meets Energy Vulnerability

After trending downward through most of 2025 alongside rand appreciation and falling oil prices, Turnleaf’s 12 month inflation forecast for South Africa is now pointing at rising inflation pressure in 2026 (Figure 1). Rebounding oil prices are overwhelming the disinflationary benefits of a stronger currency, exposing South Africa’s structural vulnerability in energy markets.

Figure 1 – (to see Turnleaf’s 12-month forecast for South Africa, visit our latest Substack post, here)

While currency appreciation against the dollar provides relief on import costs, the country’s near-total dependence on imported oil creates a direct transmission channel from global energy markets into domestic prices—one that operates faster and more forcefully than the gradual benefits of rand strength. When oil prices turn upward, as they have since late 2025, South Africa’s energy sector becomes the dominant inflation driver, regardless of what’s happening with the exchange rate.

The Currency Cushion: Real But Limited

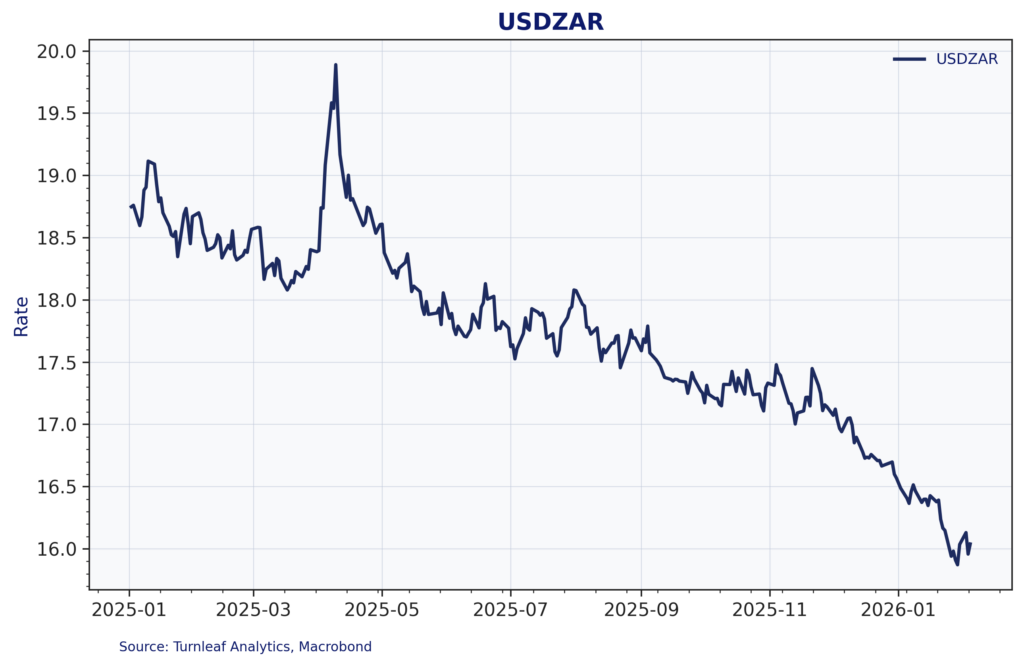

The rand’s performance through 2025 was remarkable. Figure 2 shows the USDZAR exchange rate declining from around 19 rand per dollar in early 2025 to approximately 16 rand per dollar by early 2026—a substantial appreciation of roughly 16%. This strengthening reflects both broad USD weakness amid geopolitical uncertainty and South Africa-specific factors, particularly the country’s position as a major gold producer during a period of surging gold prices.

Figure 2: USDZAR Exchange Rate

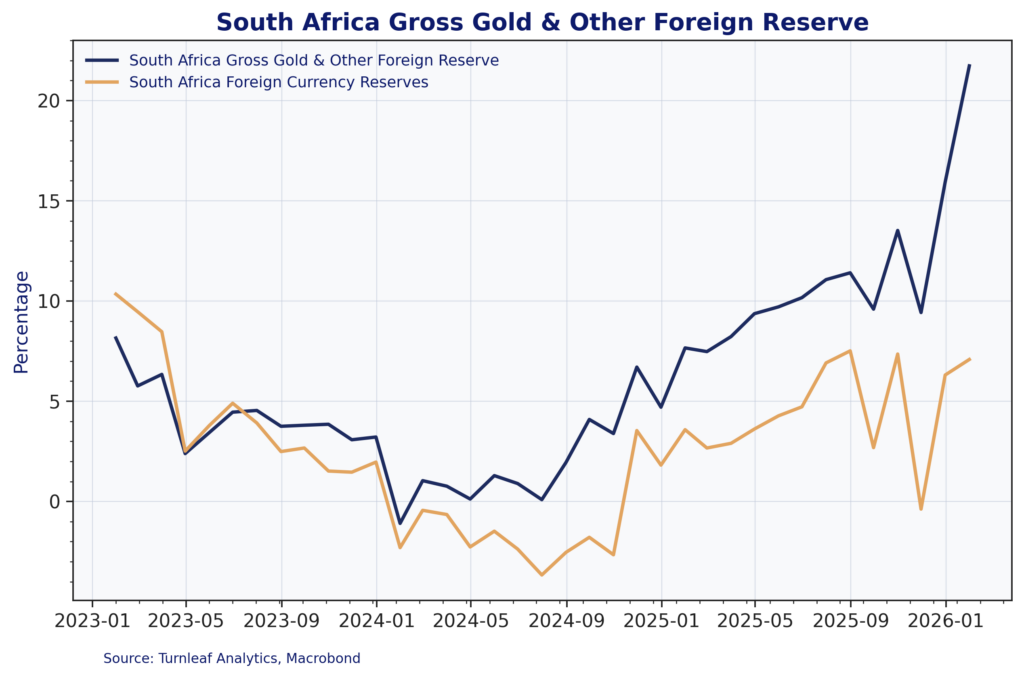

Gold’s role here deserves attention. Figure 3 shows gold prices surging from around $2,000 per ounce in early 2024 to a peak above $5,400 in late 2025, driven by the metal’s emerging role as an alternative reserve asset in global financial transactions. While gold has since pulled back to around $4,800 per ounce in early February 2026, the sustained elevation in prices has delivered a substantial windfall to South Africa’s mining sector and export revenues.

Figure 3: Gold Prices (USD/oz)

This gold windfall strengthened South Africa’s external position in measurable ways. Figure 4 shows gold and other reserves increasing sharply as a share of total reserves, rising from around 10% to over 21% by early 2026, while traditional foreign currency reserves remained relatively stable. This reserve accumulation has provided the South African Reserve Bank with greater policy flexibility and reduced the near-term pressure for currency intervention.

Figure 4: South Africa Reserve Composition

The combination of USD weakness, gold export revenues, and reserve accumulation has given South Africa breathing room on the currency front. Rand appreciation naturally reduces import costs and provides disinflationary support. But this cushion proves insufficient when set against the country’s structural energy vulnerabilities.

The Energy Transmission: Fast and Forceful

South Africa’s inflation vulnerability centers on oil, not because of any particular policy failure but because of unavoidable geography and infrastructure constraints. The country imports approximately 95% of its petroleum consumption, with international crude prices—denominated in USD—accounting for roughly 50% of domestic fuel costs. This creates a direct, rapid transmission from global oil markets to South African consumer prices through the monthly fuel price adjustment mechanism.

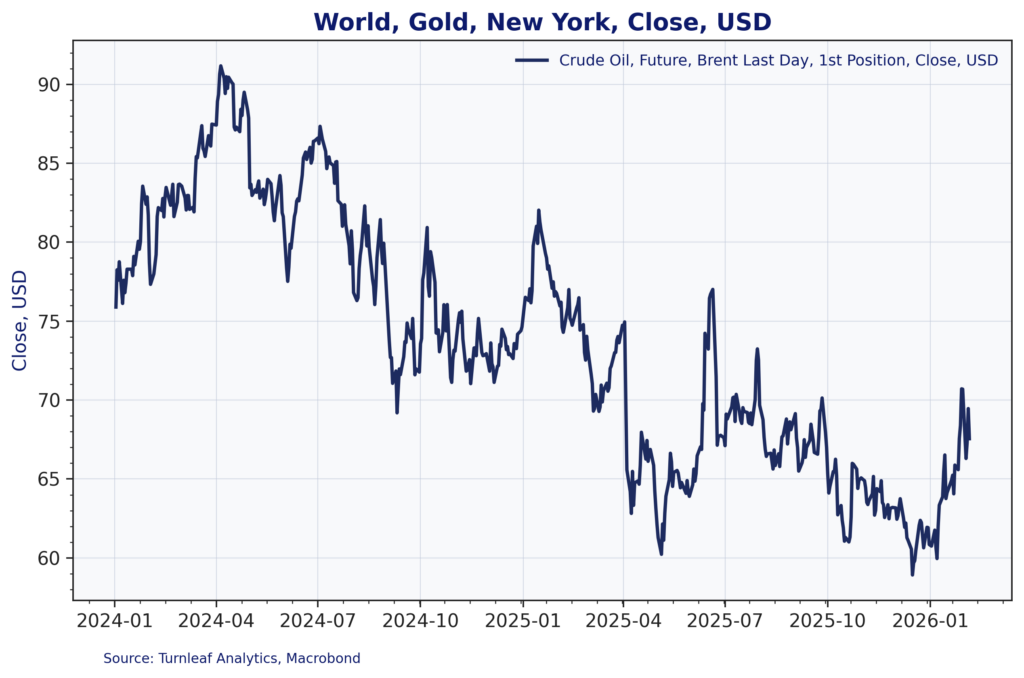

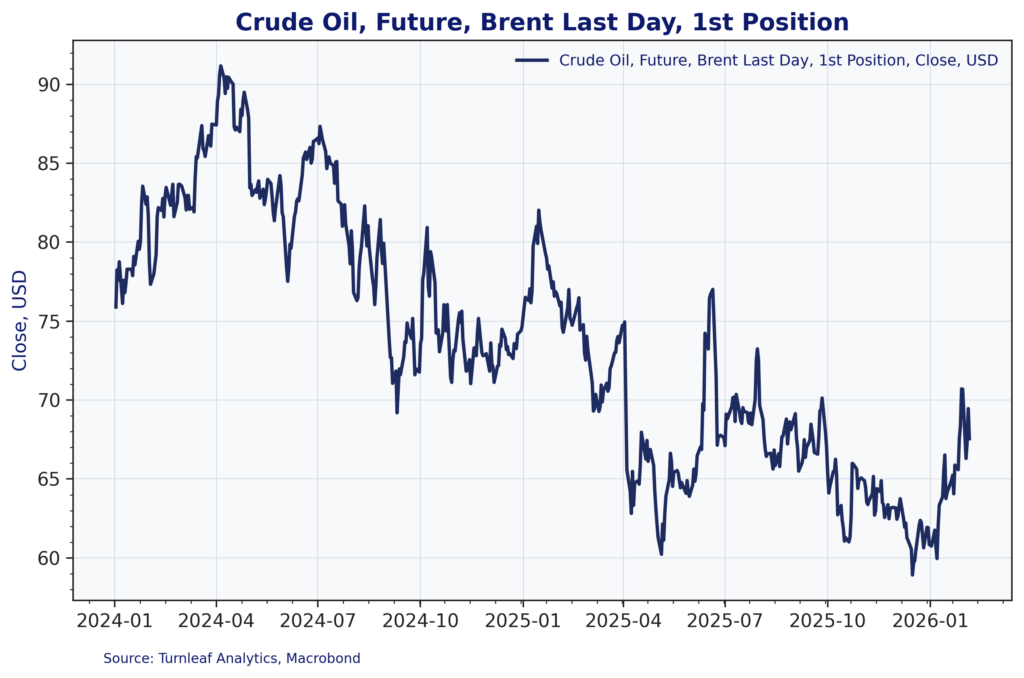

International oil prices have moved dramatically over the past two years. Figure 5 shows Brent crude peaking near $90 per barrel in mid-2024, then declining substantially through 2025 to reach lows near $60 per barrel in late 2025. This extended decline provided significant disinflationary relief and contributed to the downward trend in our inflation forecasts through most of 2025.

Figure 5: Brent Crude Oil Prices (USD/bbl)

But the oil story has reversed. Brent crude has rebounded from its late-2025 lows and is now trading back toward $70 per barrel in early 2026. This $10 increase, while modest in absolute terms, matters enormously for South African inflation because it operates through a direct, mechanical transmission channel with minimal lags.

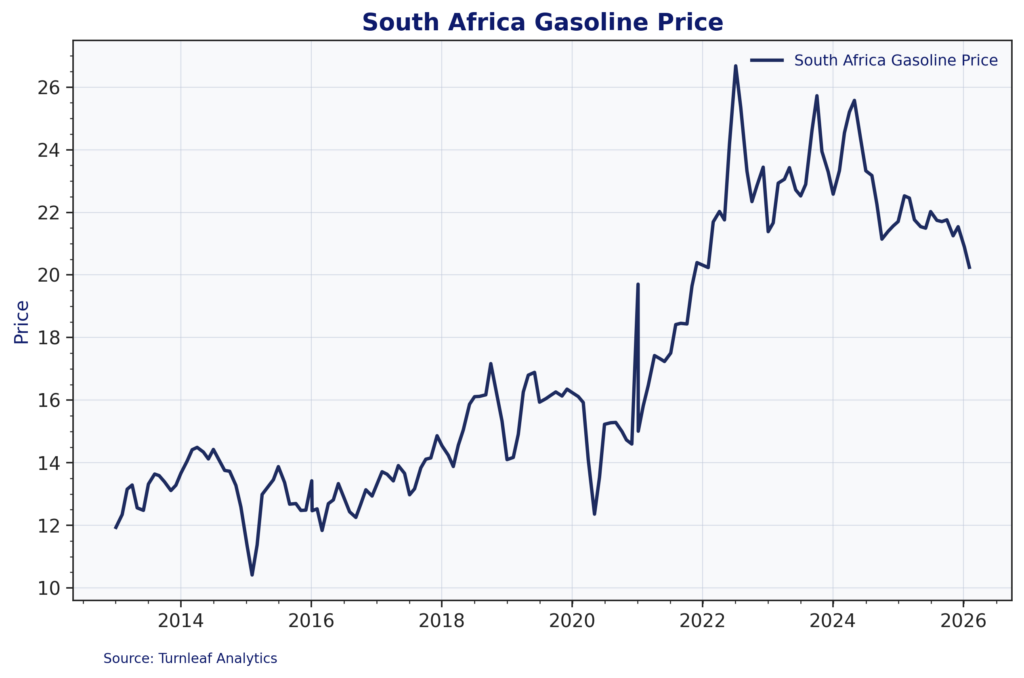

Figure 6 illustrates the domestic impact. South African gasoline prices rose from around 14-15 rand per liter in 2020-2021 to peaks above 26 rand per liter in 2023, before moderating to around 20-21 rand per liter in early 2026.

Figure 6: South Africa Gasoline Prices (ZAR/liter)

The monthly adjustment mechanism means any movement in international oil prices or the USDZAR exchange rate translates quickly into pump prices. Even as rand strength provides some offset, rising crude prices feed through rapidly.

The oil transmission extends beyond direct fuel costs into the electricity sector, amplifying the inflationary impact. Eskom, South Africa’s state-owned utility, relies on coal for 80-90% of generation but must turn to diesel-powered backup generation during peak demand periods or when coal units fail. This diesel dependency creates a direct link between global oil markets and electricity costs, adding a second transmission channel for oil price movements.

Recent improvements in Eskom’s operational performance—including better coal unit reliability and reduced diesel consumption—have moderated this channel somewhat. Reports from early 2026 indicate meaningful progress in energy capacity performance. However, these operational improvements, while welcome, do not eliminate South Africa’s fundamental energy vulnerability. The direct fuel price channel remains dominant, and any significant oil price increase will flow through to inflation regardless of marginal improvements in Eskom’s diesel consumption.

Please see our Substack for the rest.

Research Archive

Macroeconomic Insights: South Africa CPI – When Currency Strength Meets Energy Vulnerability

After trending downward through most of 2025 alongside rand appreciation and falling oil prices, Turnleaf’s 12 month inflation forecast for South Africa is now pointing at rising...

Macroeconomic Insights: Colombia CPI: The Minimum Wage Shock

Colombia’s 12-month inflation outlook for 2026 has been revised higher. We now expect inflation to hit up to 6.7%YoY by the end of the year (Figure 1). This is a clear break from...

Macroeconomic Insights: Expect the Unexpected

Mark Carney at Davos, January 20, 2026 "For decades, countries like Canada prospered under what we called the rules-based international order. We joined its institutions, we...

Macroeconomic Insights: Eurozone CPI — “Sweater Weather” Is Repricing Energy Risk

Energy markets have moved back to the foreground as a near-term driver of Eurozone headline inflation. Colder January temperatures lifted heating and power demand into a winter...

AI coding is like making a burger with sugar

Have you ever had a burger, and then noticed something is kind of off. You’re hunting for the reason. Then it’s immediately obvious: they put sugar instead of salt. Ok, this has...

Macroeconomic Insights: Turkey CPI – Inflation Pinned in Gold

Gold jewelry remains a common wedding gift in Turkey, reflecting a cultural practice where households preserve wealth through physical gold rather than financial assets. This...

Macroeconomic Insights: US CPI – November’s Weakness is Not All December’s Gain

The October–November 2025 CPI sequence contained meaningful measurement distortions linked to the federal government shutdown. BLS has since confirmed that most CPI operations...

Macroeconomic Insights: Colombia CPI – Minimum Wage Shock Meets Fiscal Emergency

Turnleaf expects Colombia CPI to accelerate towards 6% YoY starting January 2026 following a 23.7% minimum wage increase that took effect on January 1—a significant upward...

Inflation Outlook 2026: New Year, New Inflation Regime?

Over the past year, global disinflation efforts have been complicated by escalating trade tensions that slowed global growth, geopolitical conflicts in the Middle East and...

Hundreds of quant papers from #QuantLinkADay in 2025

I tweet a lot (from @saeedamenfx and at BlueSky at @saeedamenfx.bsky.social)! In amongst the tweets about burgers, I tweet out a quant paper or link every day under the hashtag...

Macroeconomic Insights: U.S. CPI – Now What?

The October and November 2025 CPI prints were materially affected by technical distortions related to the federal government shutdown. These distortions are likely to produce a...

Macroeconomic Insights: What Drove US CPI Lower?

US CPI YoY NSA came in at 2.7%, significantly below consensus expectations (3.1%) and our own model forecast (3.0%). Core CPI YoY NSA also printed weaker at 2.6% versus market...

Macroeconomic Insights: Chile CPI – It’s Not All That Bad

Turnleaf expects Chilean inflation to ease below the central bank's 3% target in early 2025, driven by peso appreciation compressing import prices and subdued energy costs...

Macroeconomic Insights: US CPI – Natural Gas Price Dynamics and Inflation Pass-Through

The recent spike in natural gas futures reflects market expectations of future supply constraints. Unlike past volatility driven by weather alone, this increase stems from...

Macroeconomic Insights: Switzerland CPI – Inflation Not Hot Not Cold

Last month Turnleaf argued that Switzerland was escaping deflation but still stuck near 0% inflation over the next year, with any firming coming mainly from tax changes and...