Bystander Effect

Explore the bystander effect, a psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to help in an emergency when others are present.

Explore the bystander effect, a psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to help in an emergency when others are present.

The bystander effect, a term deeply embedded in social psychology, encapsulates the perplexing human tendency to become an unresponsive bystander during emergencies when others are present.

| Increases Intervention | Example | Decreases Intervention | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small group size | One or two witnesses present | Large group size | Many people observing the incident |

| Clear emergency | Obvious signs of distress or danger | Ambiguous situation | Unclear if help is needed |

| Personal responsibility | Being the only witness or directly addressed | Diffusion of responsibility | Assuming someone else will help |

| Competence/training | First aid training or relevant expertise | Lack of skills | Unsure how to help effectively |

| Personal connection | Knowing the victim or shared identity | Anonymity | Being a stranger in a crowd |

This phenomenon, often attributed to a diffusion of responsibility, leads to a decreased likelihood of intervention, as individuals unconsciously assume that someone else will take action.

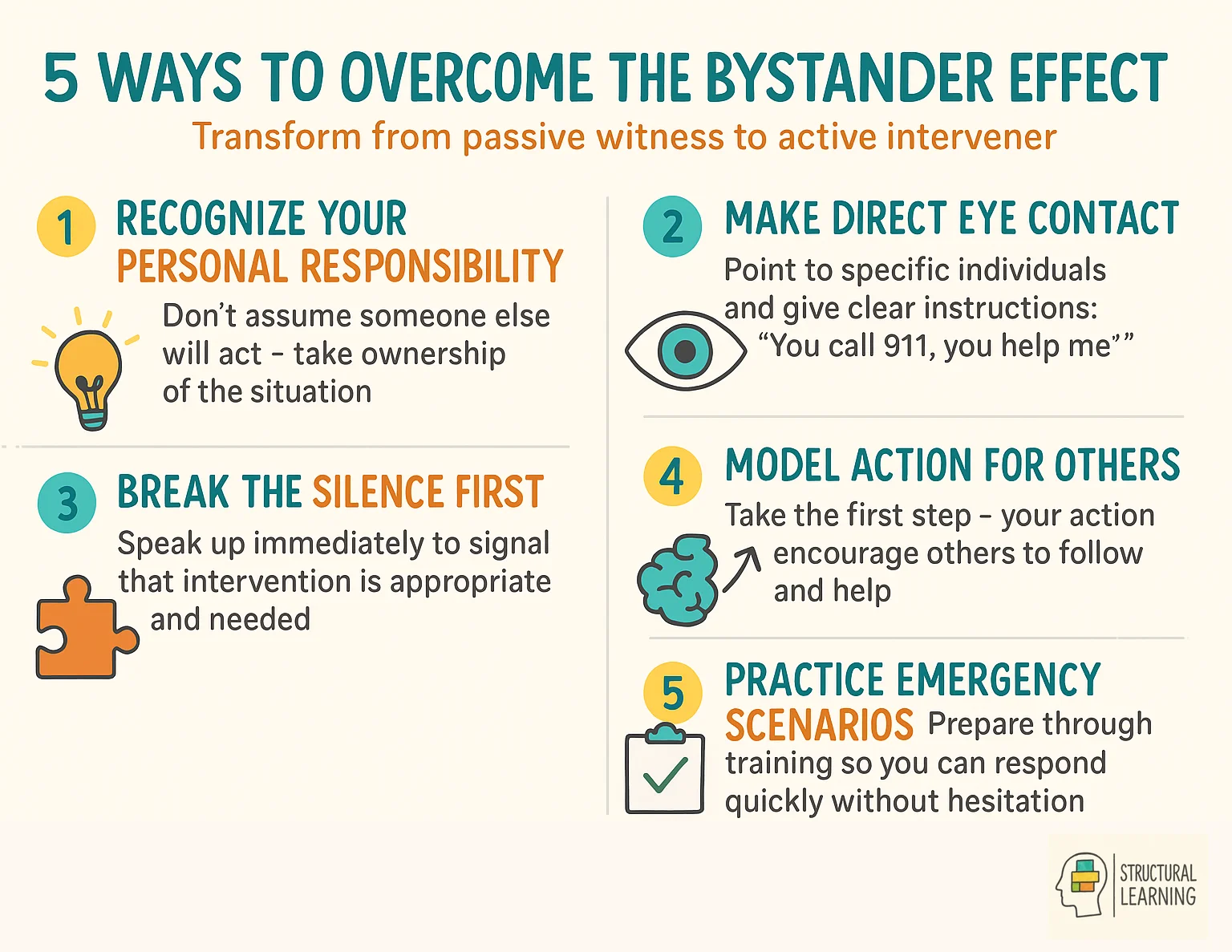

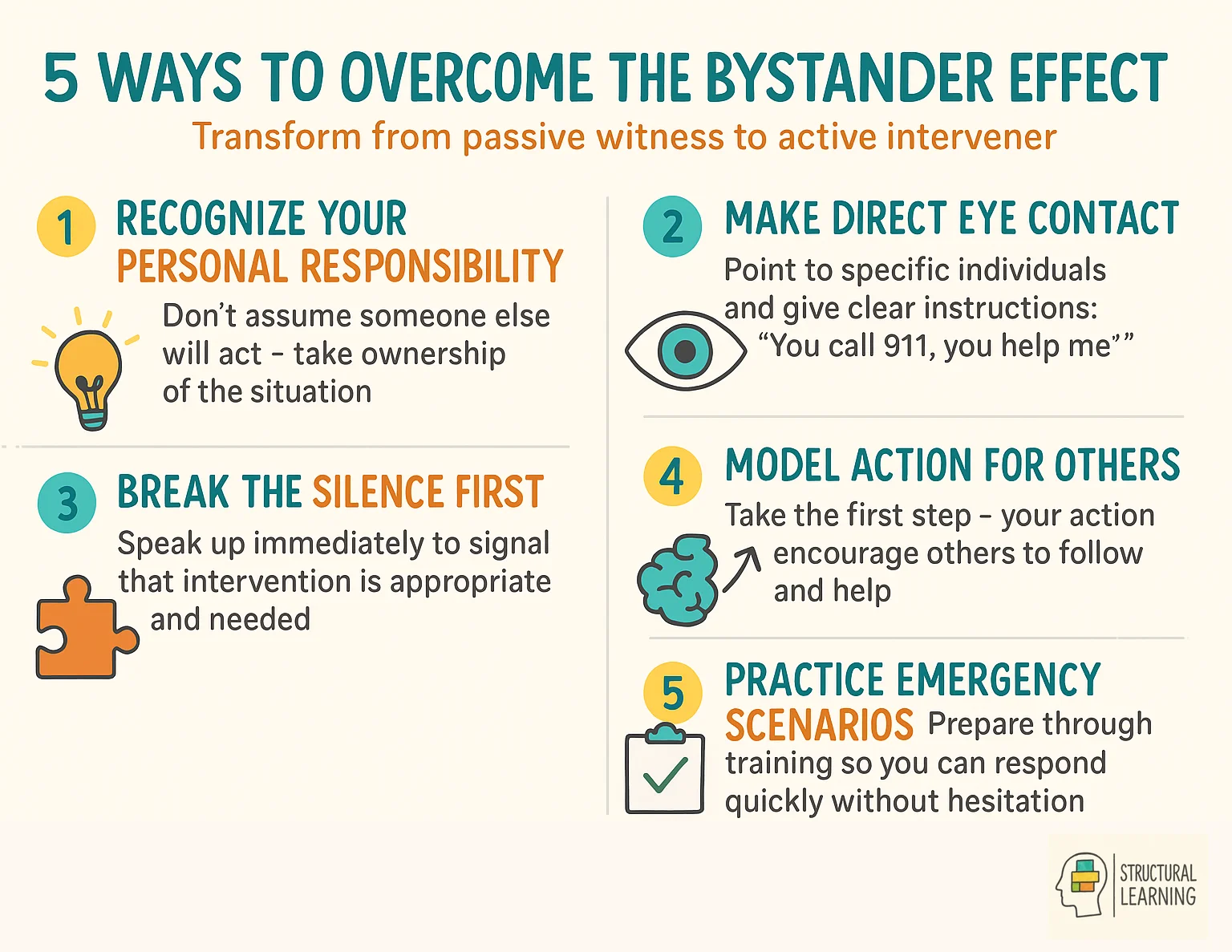

practical strategies to overcome bystander effect and become an active intervener in emergencies" loading="lazy">

practical strategies to overcome bystander effect and become an active intervener in emergencies" loading="lazy">For instance, in a crowded school hallway where bullying is occurring, bystanders may overlook the situation, believing that another person will step in, thereby contributing to a collective inaction. This highlights the importance of implementing targeted classroom management strategies that enable pupils to become active participants rather than passive observers.

This effect was tragically illustrated in the case of Kitty Genovese in 1964, where her brutal attack was witnessed by several individuals who failed to intervene or call for help. This incident not only shocked the public but also ignited a spark in the field of social psychology, leading to extensive research, including studies published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

One relevant statistic that underscores the gravity of this issue is that in situations with more th an five bystanders, the likelihood of intervention drops by over 50%. The bystander effect is not merely a curiosity; it's a profound insight into human behaviour that has real emergency implications in our crowded minds.

Understanding bystander behaviour is crucial in today's interconnected world. It's not just about public self-awareness but about encouraging a sense of res ponsibility on bystander intervention.

Through targeted modelling strategies and targeted education and bystander training, we can challenge the implicit bystander theory that often governs our reactions, enabling individuals to transcend passivity and actively assist those in distress.

Key Insights and Important Facts:

Social influences create the bystander effect through diffusion of responsibility, where individuals assume others will take action, and pluralistic ignorance, where people misinterpret others' inaction as appropriate behaviour. The presence of more people actually reduces individual responsibility and increases conformity to perceived group norms. These psychological mechanisms explain why crowded environments often see less intervention during emergencies or incidents.

The bystander effect, a phenomenon in which individuals are less likely to intervene in emergency situations when other people are present, can be attributed in part to social influences. One key factor contributing to the bystander effect is the diffusion of responsibility.

When faced with an emergency situation, individuals may feel less personally responsible to take action because they assume that someone else will step in and help. This diffusion of responsibility can lead to inaction and a lack of intervention, which is similar to patterns observed in the Dunning-Kruger Effect where cognitive biases affect decision-making.

Social influence also plays a role in the bystander effect. According to social comparison theory, individuals tend to look to others for cues on how to behave in ambiguous situations.

In emergency situations, if bystanders observe others not taking action, they may interpret this as a signal that help is not needed or that it is not their responsibility to intervene. This phenomenon, known as pluralistic ignorance, further inhibits bystander intervention and is particularly relevant when considering social-emotional learning in educational contexts.

These social influences contribute to the bystander effect by creating a sense of shared responsibility that paradoxically reduces individual action. Understanding these mechanisms can help educators develop strategies that promote student wellbeing and encourage intervention when peers need support. This understanding also relates to how attention is directed and how motivation to help others can be enhanced through proper training and awareness. Additionally, providing appropriate scaffolding can help students develop the confidence to act when they witness concerning situations, while feedback mechanisms can reinforce positive intervention behaviours.

To counteract these psychological barriers, educators can implement specific strategies that prepare students to overcome bystander inaction. Pre-commitment techniques involve helping students mentally rehearse scenarios and decide in advance how they would respond, reducing the cognitive load during actual incidents. Role-playing exercises allow students to practice intervention skills in safe environments, building confidence and familiarity with appropriate responses.

Pluralistic ignorance training teaches students to recognise when their interpretation of others' calm behaviour may be incorrect. Educators can demonstrate how people often mask their concern or uncertainty, helping students understand that apparent indifference doesn't necessarily indicate that intervention is unnecessary. Additionally, teaching students about graduated response options - from seeking adult help to direct intervention - provides them with a toolkit of actions that vary in personal risk and commitment.

Creating classroom discussions around these psychological mechanisms helps normalise the experience of feeling uncertain or hesitant in challenging situations. When students understand that bystander behaviour stems from predictable psychological processes rather than moral failings, they become more equipped to recognise these patterns in themselves and develop strategies to overcome them in educational settings and beyond.

The bystander effect gained widespread attention following the 1964 murder of Kitty Genovese in New York City, where numerous witnesses allegedly failed to intervene or call for help. While later investigations revealed inaccuracies in initial reports, this case prompted psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latané to conduct groundbreaking experiments in the late 1960s. Their research demonstrated that individuals are less likely to help when other bystanders are present, revealing key factors such as diffusion of responsibility and pluralistic ignorance that inhibit prosocial behaviour.

Darley and Latané's seminal studies included staged emergencies where participants believed they were either alone or with others when witnessing someone in distress. Results consistently showed that help-seeking behaviour decreased as the number of perceived bystanders increased. Their work established that bystander intervention follows a cognitive process involving noticing the event, interpreting it as an emergency, accepting responsibility, and possessing the skills to help.

For educators, these findings highlight the importance of explicitly teaching intervention strategies and creating classroom cultures where individual responsibility is emphasised. When addressing bullying or peer conflicts, teachers can reference specific students by name rather than making general appeals to the class, thereby reducing diffusion of responsibility and encouraging active bystander behaviour in educational settings.

Research by social psychologists Darley and Latané reveals that the bystander effect can be significantly reduced through targeted educational interventions. Direct instruction about the phenomenon itself proves particularly effective, as awareness o f diffusion of responsibility helps individuals recognise when they might be falling into passive bystander behaviour. Students who understand the psychological mechanisms behind inaction are more likely to take appropriate action when witnessing concerning situations.

Practical strategies for overcoming the bystander effect centre on specific action planning and role clarification. Teaching students to mentally rehearse intervention scenarios, identify clear steps for seeking help, and understand their personal responsibility creates cognitive pathways that bypass the paralysis often associated with emergency situations. Bandura's social learning theory supports the use of modelled behaviour and peer observation to normalise helpful intervention.

In educational settings, establishing clear reporting procedures and creating a culture of shared responsibility proves essential. Students benefit from understanding exactly whom to approach, when to intervene directly, and how to access appropriate support systems. Regular discussion of scenarios relevant to school environments, combined with explicit teaching about upstander behaviour, transforms theoretical knowledge into practical action. This approach effectively counters the diffusion of responsibility that characterises bystander behaviour in group settings.

The bystander effect manifests prominently in educational settings, where students frequently witness incidents requiring intervention but fail to act due to diffusion of responsibility amongst peers. Research by Latané and Darley demonstrates that this psychological phenomenon occurs when individuals assume others will take action, particularly in situations involving bullying, academic dishonesty, or students experiencing distress. In classroom environments, this behaviour pattern can perpetuate harmful dynamics and undermine the supportive learning community educators strive to create.

Educational settings present unique challenges for addressing bystander behaviour, as students often fear social repercussions, lack confidence in their ability to help effectively, or misinterpret situations as less serious than they actually are. When witnessing cyberbullying, cheating, or peer exclusion, students may rationalise their inaction by believing teachers should handle such matters or that their intervention might worsen the situation.

Educators can combat the bystander effect by implementing explicit instruction about prosocial behaviour and creating clear protocols for reporting concerns. Establishing classroom norms that emphasise collective responsibility for maintaining a positive learning environment helps students to act. Role-playing exercises and discussing real scenarios help students recognise situations requiring intervention whilst building their confidence to respond appropriately, whether through direct action or seeking adult assistance.

The digital age has fundamentally transformed how bystander behaviour manifests in educational environments, extending the psychological phenomenon beyond physical spaces into online platforms where students spend increasing amounts of time. Research by Kowalski and Limber demonstrates that cyberbullying incidents often involve numerous silent observers who witness harmful content but fail to intervene, mirroring the diffusion of responsibility seen in traditional bystander situations. However, digital contexts present unique challenges: the perceived anonymity of online spaces, the asynchronous nature of digital communication, and the broader potential audience all amplify both the harm and the bystander effect.

Social psychology research indicates that online bystanders face additional barriers to intervention, including technological distance from the victim and uncertainty about appropriate digital responses. The permanence of digital content means that harmful material can circulate indefinitely, yet this same permanence creates opportunities for positive bystander intervention through reporting mechanisms and supportive comments.

Educators must therefore expand traditional bystander intervention training to include digital literacy and online citizenship skills. Practical approaches include teaching students to recognise cyberbullying, demonstrating how to safely report incidents through platform-specific tools, and encouraging supportive private messaging to victims. Creating classroom discussions about digital bystander scenarios helps students develop confidence in online intervention strategies.

The bystander effect, a term deeply embedded in social psychology, encapsulates the perplexing human tendency to become an unresponsive bystander during emergencies when others are present.

| Increases Intervention | Example | Decreases Intervention | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small group size | One or two witnesses present | Large group size | Many people observing the incident |

| Clear emergency | Obvious signs of distress or danger | Ambiguous situation | Unclear if help is needed |

| Personal responsibility | Being the only witness or directly addressed | Diffusion of responsibility | Assuming someone else will help |

| Competence/training | First aid training or relevant expertise | Lack of skills | Unsure how to help effectively |

| Personal connection | Knowing the victim or shared identity | Anonymity | Being a stranger in a crowd |

This phenomenon, often attributed to a diffusion of responsibility, leads to a decreased likelihood of intervention, as individuals unconsciously assume that someone else will take action.

practical strategies to overcome bystander effect and become an active intervener in emergencies" loading="lazy">

practical strategies to overcome bystander effect and become an active intervener in emergencies" loading="lazy">For instance, in a crowded school hallway where bullying is occurring, bystanders may overlook the situation, believing that another person will step in, thereby contributing to a collective inaction. This highlights the importance of implementing targeted classroom management strategies that enable pupils to become active participants rather than passive observers.

This effect was tragically illustrated in the case of Kitty Genovese in 1964, where her brutal attack was witnessed by several individuals who failed to intervene or call for help. This incident not only shocked the public but also ignited a spark in the field of social psychology, leading to extensive research, including studies published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

One relevant statistic that underscores the gravity of this issue is that in situations with more th an five bystanders, the likelihood of intervention drops by over 50%. The bystander effect is not merely a curiosity; it's a profound insight into human behaviour that has real emergency implications in our crowded minds.

Understanding bystander behaviour is crucial in today's interconnected world. It's not just about public self-awareness but about encouraging a sense of res ponsibility on bystander intervention.

Through targeted modelling strategies and targeted education and bystander training, we can challenge the implicit bystander theory that often governs our reactions, enabling individuals to transcend passivity and actively assist those in distress.

Key Insights and Important Facts:

Social influences create the bystander effect through diffusion of responsibility, where individuals assume others will take action, and pluralistic ignorance, where people misinterpret others' inaction as appropriate behaviour. The presence of more people actually reduces individual responsibility and increases conformity to perceived group norms. These psychological mechanisms explain why crowded environments often see less intervention during emergencies or incidents.

The bystander effect, a phenomenon in which individuals are less likely to intervene in emergency situations when other people are present, can be attributed in part to social influences. One key factor contributing to the bystander effect is the diffusion of responsibility.

When faced with an emergency situation, individuals may feel less personally responsible to take action because they assume that someone else will step in and help. This diffusion of responsibility can lead to inaction and a lack of intervention, which is similar to patterns observed in the Dunning-Kruger Effect where cognitive biases affect decision-making.

Social influence also plays a role in the bystander effect. According to social comparison theory, individuals tend to look to others for cues on how to behave in ambiguous situations.

In emergency situations, if bystanders observe others not taking action, they may interpret this as a signal that help is not needed or that it is not their responsibility to intervene. This phenomenon, known as pluralistic ignorance, further inhibits bystander intervention and is particularly relevant when considering social-emotional learning in educational contexts.

These social influences contribute to the bystander effect by creating a sense of shared responsibility that paradoxically reduces individual action. Understanding these mechanisms can help educators develop strategies that promote student wellbeing and encourage intervention when peers need support. This understanding also relates to how attention is directed and how motivation to help others can be enhanced through proper training and awareness. Additionally, providing appropriate scaffolding can help students develop the confidence to act when they witness concerning situations, while feedback mechanisms can reinforce positive intervention behaviours.

To counteract these psychological barriers, educators can implement specific strategies that prepare students to overcome bystander inaction. Pre-commitment techniques involve helping students mentally rehearse scenarios and decide in advance how they would respond, reducing the cognitive load during actual incidents. Role-playing exercises allow students to practice intervention skills in safe environments, building confidence and familiarity with appropriate responses.

Pluralistic ignorance training teaches students to recognise when their interpretation of others' calm behaviour may be incorrect. Educators can demonstrate how people often mask their concern or uncertainty, helping students understand that apparent indifference doesn't necessarily indicate that intervention is unnecessary. Additionally, teaching students about graduated response options - from seeking adult help to direct intervention - provides them with a toolkit of actions that vary in personal risk and commitment.

Creating classroom discussions around these psychological mechanisms helps normalise the experience of feeling uncertain or hesitant in challenging situations. When students understand that bystander behaviour stems from predictable psychological processes rather than moral failings, they become more equipped to recognise these patterns in themselves and develop strategies to overcome them in educational settings and beyond.

The bystander effect gained widespread attention following the 1964 murder of Kitty Genovese in New York City, where numerous witnesses allegedly failed to intervene or call for help. While later investigations revealed inaccuracies in initial reports, this case prompted psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latané to conduct groundbreaking experiments in the late 1960s. Their research demonstrated that individuals are less likely to help when other bystanders are present, revealing key factors such as diffusion of responsibility and pluralistic ignorance that inhibit prosocial behaviour.

Darley and Latané's seminal studies included staged emergencies where participants believed they were either alone or with others when witnessing someone in distress. Results consistently showed that help-seeking behaviour decreased as the number of perceived bystanders increased. Their work established that bystander intervention follows a cognitive process involving noticing the event, interpreting it as an emergency, accepting responsibility, and possessing the skills to help.

For educators, these findings highlight the importance of explicitly teaching intervention strategies and creating classroom cultures where individual responsibility is emphasised. When addressing bullying or peer conflicts, teachers can reference specific students by name rather than making general appeals to the class, thereby reducing diffusion of responsibility and encouraging active bystander behaviour in educational settings.

Research by social psychologists Darley and Latané reveals that the bystander effect can be significantly reduced through targeted educational interventions. Direct instruction about the phenomenon itself proves particularly effective, as awareness o f diffusion of responsibility helps individuals recognise when they might be falling into passive bystander behaviour. Students who understand the psychological mechanisms behind inaction are more likely to take appropriate action when witnessing concerning situations.

Practical strategies for overcoming the bystander effect centre on specific action planning and role clarification. Teaching students to mentally rehearse intervention scenarios, identify clear steps for seeking help, and understand their personal responsibility creates cognitive pathways that bypass the paralysis often associated with emergency situations. Bandura's social learning theory supports the use of modelled behaviour and peer observation to normalise helpful intervention.

In educational settings, establishing clear reporting procedures and creating a culture of shared responsibility proves essential. Students benefit from understanding exactly whom to approach, when to intervene directly, and how to access appropriate support systems. Regular discussion of scenarios relevant to school environments, combined with explicit teaching about upstander behaviour, transforms theoretical knowledge into practical action. This approach effectively counters the diffusion of responsibility that characterises bystander behaviour in group settings.

The bystander effect manifests prominently in educational settings, where students frequently witness incidents requiring intervention but fail to act due to diffusion of responsibility amongst peers. Research by Latané and Darley demonstrates that this psychological phenomenon occurs when individuals assume others will take action, particularly in situations involving bullying, academic dishonesty, or students experiencing distress. In classroom environments, this behaviour pattern can perpetuate harmful dynamics and undermine the supportive learning community educators strive to create.

Educational settings present unique challenges for addressing bystander behaviour, as students often fear social repercussions, lack confidence in their ability to help effectively, or misinterpret situations as less serious than they actually are. When witnessing cyberbullying, cheating, or peer exclusion, students may rationalise their inaction by believing teachers should handle such matters or that their intervention might worsen the situation.

Educators can combat the bystander effect by implementing explicit instruction about prosocial behaviour and creating clear protocols for reporting concerns. Establishing classroom norms that emphasise collective responsibility for maintaining a positive learning environment helps students to act. Role-playing exercises and discussing real scenarios help students recognise situations requiring intervention whilst building their confidence to respond appropriately, whether through direct action or seeking adult assistance.

The digital age has fundamentally transformed how bystander behaviour manifests in educational environments, extending the psychological phenomenon beyond physical spaces into online platforms where students spend increasing amounts of time. Research by Kowalski and Limber demonstrates that cyberbullying incidents often involve numerous silent observers who witness harmful content but fail to intervene, mirroring the diffusion of responsibility seen in traditional bystander situations. However, digital contexts present unique challenges: the perceived anonymity of online spaces, the asynchronous nature of digital communication, and the broader potential audience all amplify both the harm and the bystander effect.

Social psychology research indicates that online bystanders face additional barriers to intervention, including technological distance from the victim and uncertainty about appropriate digital responses. The permanence of digital content means that harmful material can circulate indefinitely, yet this same permanence creates opportunities for positive bystander intervention through reporting mechanisms and supportive comments.

Educators must therefore expand traditional bystander intervention training to include digital literacy and online citizenship skills. Practical approaches include teaching students to recognise cyberbullying, demonstrating how to safely report incidents through platform-specific tools, and encouraging supportive private messaging to victims. Creating classroom discussions about digital bystander scenarios helps students develop confidence in online intervention strategies.

{"@context":"https://schema.org","@graph":[{"@type":"Article","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/bystander-effect#article","headline":"Bystander Effect","description":"Explore the bystander effect, a psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to help in an emergency when others are present.","datePublished":"2023-08-01T11:15:03.859Z","dateModified":"2026-01-26T10:09:32.212Z","author":{"@type":"Person","name":"Paul Main","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com/team/paulmain","jobTitle":"Founder & Educational Consultant"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Structural Learning","url":"https://www.structural-learning.com","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409e5d5e055c6/6040bf0426cb415ba2fc7882_newlogoblue.svg"}},"mainEntityOfPage":{"@type":"WebPage","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/bystander-effect"},"image":"https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/5b69a01ba2e409501de055d1/69523c5000ac2e1d5eb40bdb_69523c4e5f6e68c050310d5f_bystander-effect-infographic.webp","wordCount":5794},{"@type":"BreadcrumbList","@id":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/bystander-effect#breadcrumb","itemListElement":[{"@type":"ListItem","position":1,"name":"Home","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":2,"name":"Blog","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/blog"},{"@type":"ListItem","position":3,"name":"Bystander Effect","item":"https://www.structural-learning.com/post/bystander-effect"}]}]}