In the world of experimentation, if you find a ‘winning variation’, you iterate (and improve). This is why Conductrics is heading back to Superweek for the 12th time in 2026. We began in 2015 as attendees and became a proud sponsor along the way. We return for more than the content; we return because it offers a rare environment where we can pause, put down our defenses, and truly listen to one another. It’s a space that prioritizes connection over transactions – where titles drop away, and honest debate happens as often by the bonfire as it does on stage.

What we’ve presented during our years at the conference has also evolved. In this post, we’re going on a small journey back in time to see how the conversation in the data industry shifted over the last decade. Join us – we’ll get you immersed in the Superweek atmosphere and industry secrets in no time!

The evolution of the conversation

If you look back at the agendas over the last decade, you can see the entire history of our industry written in the talk titles. Conductrics was there every step of the way, often providing scientific guardrails for emerging trends.

Building the foundation (2015-2017)

This was the time for mastering the how – discussing the tools, the possibilities for collecting data, and defining the strategy. Simo Ahava empowered analysts to take control of their data pipelines, encouraging them to think outside the box when using GA and GTM to collect it. Avinash Kaushik provided them with the strategic framework (like See-Think-Do-Care) to give that data purpose.

With that strong foundation already in place, Conductrics’ role was to help make the right decisions. Once you have a way to collect information and a clear objective in mind, how do you ensure you choose the best path to do it?

In our first session, we discussed how machine learning can help automate decision-making at scale. By 2017, we were introducing Reinforcement Learning to solve multi-touch problems. AI was just beginning to enter mainstream conversation at the time, primarily through news about DeepMind’s AlphaGo beating the world’s top Go players. Superweek has always been the place to discover and discuss the future of analytics.

Navigating complexity (2018-2020)

These next few years included discussions on how to be more intentional in applying analytic theory. Charles Farina’s “Let’s actually use analytics to do something” and Mariia Bocheva’s “Website analytics: the missing manual” were just a few examples of experts encouraging people not to be afraid and take action on their data.

Machine learning became more mainstream as well – in 2018 alone, seven different presentations touched on this subject. Jim Sterne was instrumental in helping marketers understand that AI wasn’t sci-fi, but an important part of their future toolkit.

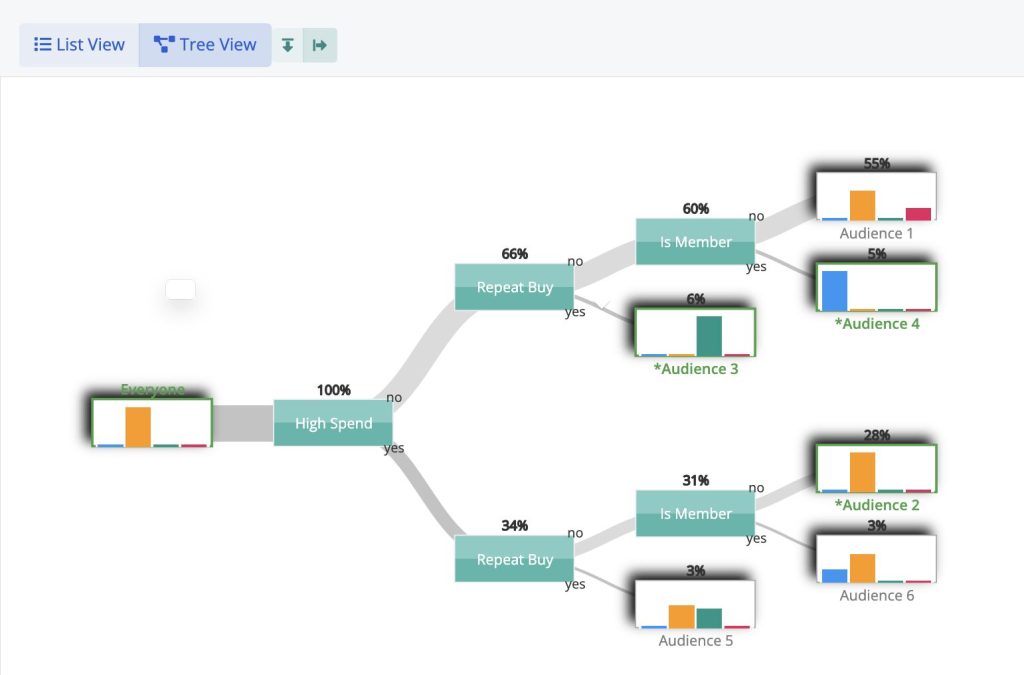

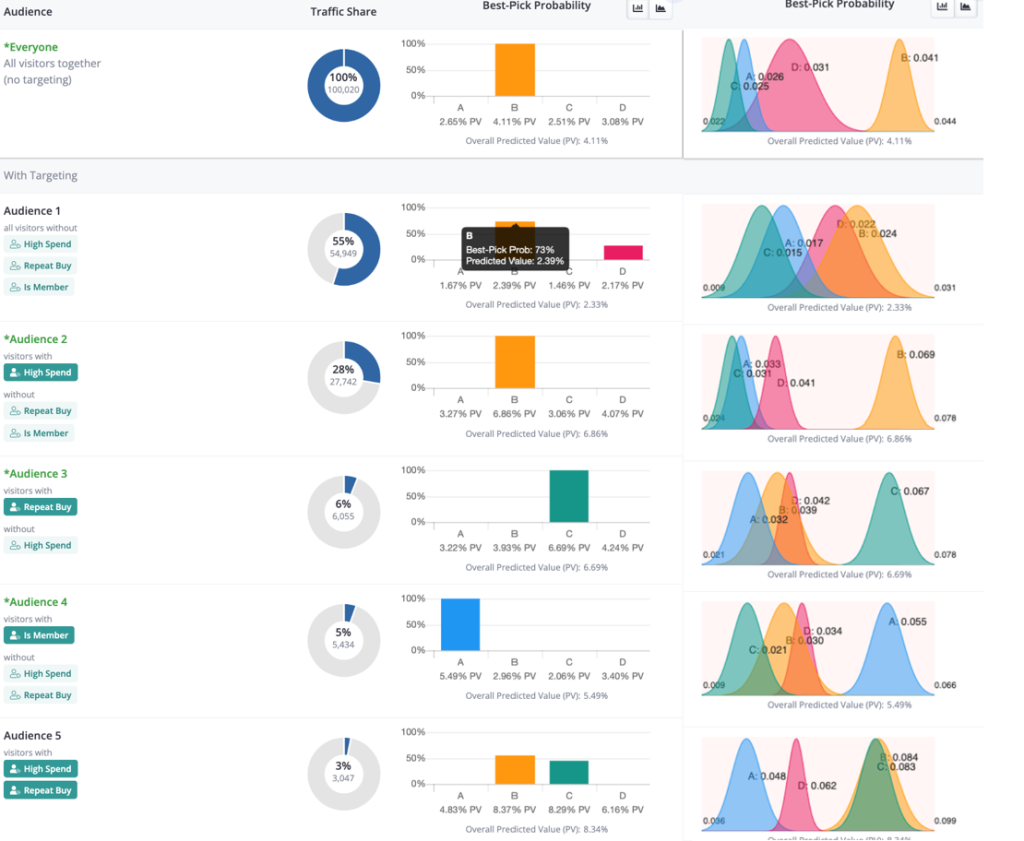

Conductrics’ own Matt Gershoff knew that for this future to work, businesses would need to trust ML before incorporating it into decision-making. Because trust requires understanding, and interpretability is the key to it, it became the theme of his presentation. In addition, interpretability was pivotal in ensuring compliance with the GDPR as it entered into force. You could feel the industry was still debating how to adopt these complex tools, which were not fully transparent nor easy to understand, while complying with the new privacy laws.

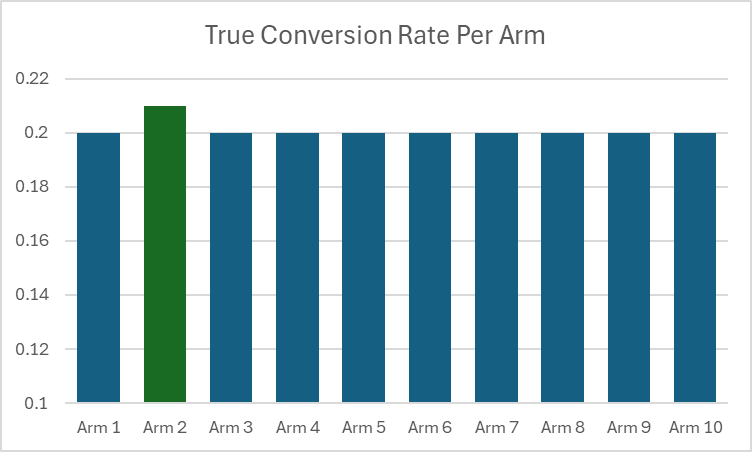

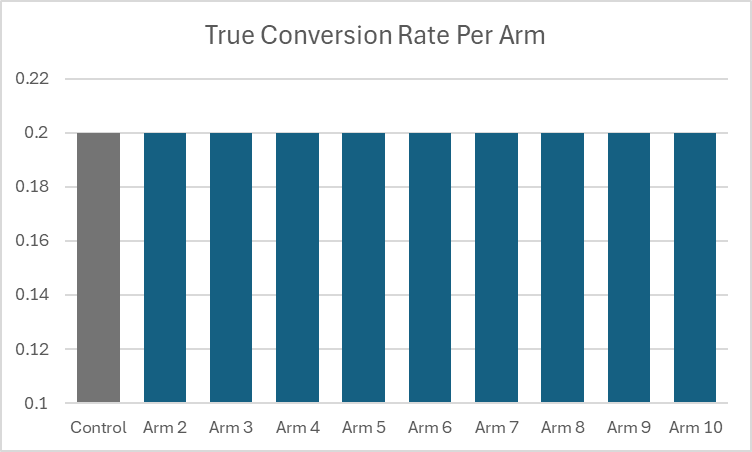

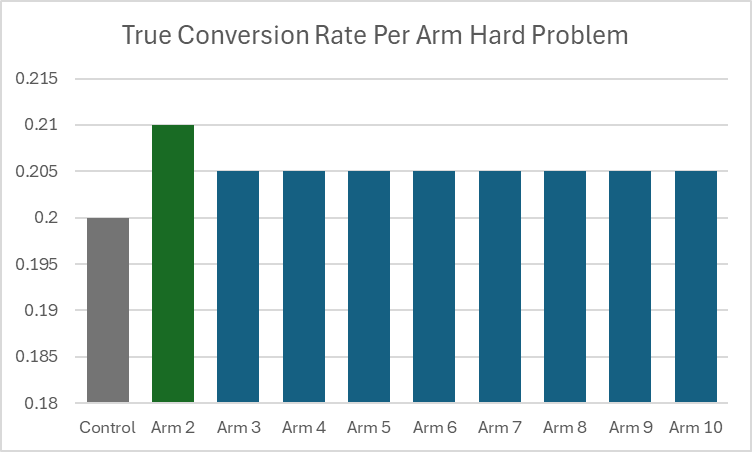

We continued to demystify this complexity in 2019 with a talk on Entropy and its use in analytics and data science. We capped off this era in 2020 with “Multi–armed bandits: Going beyond A/B testing”, demonstrating that sophisticated methods can be practical, accessible tools for optimization.

2021 – what a year!

A lot could be said about the 2021 Superweek edition, but there is one thing that’s more important than anything – Fred Pike’s banana bread. Fred, if you’re reading this, we need that recipe.

Engineering for integrity (2022 – 2025)

The Superweeks of the first half of the 2020s focused on balancing the benefits of collecting data and information about customers and their behavior with the need for responsible, privacy-compliant practices. Experts like Aurélie Pols (who spent years warning us about privacy risks and the importance of data ethics) and Karolina Wrzask (who advocated for data minimization in her ‘We don’t need all your data. Neither do you.’ talk) were at the forefront of this change.

And once again, Conductrics was right there to lead and support, providing engineering answers to these ethical questions.

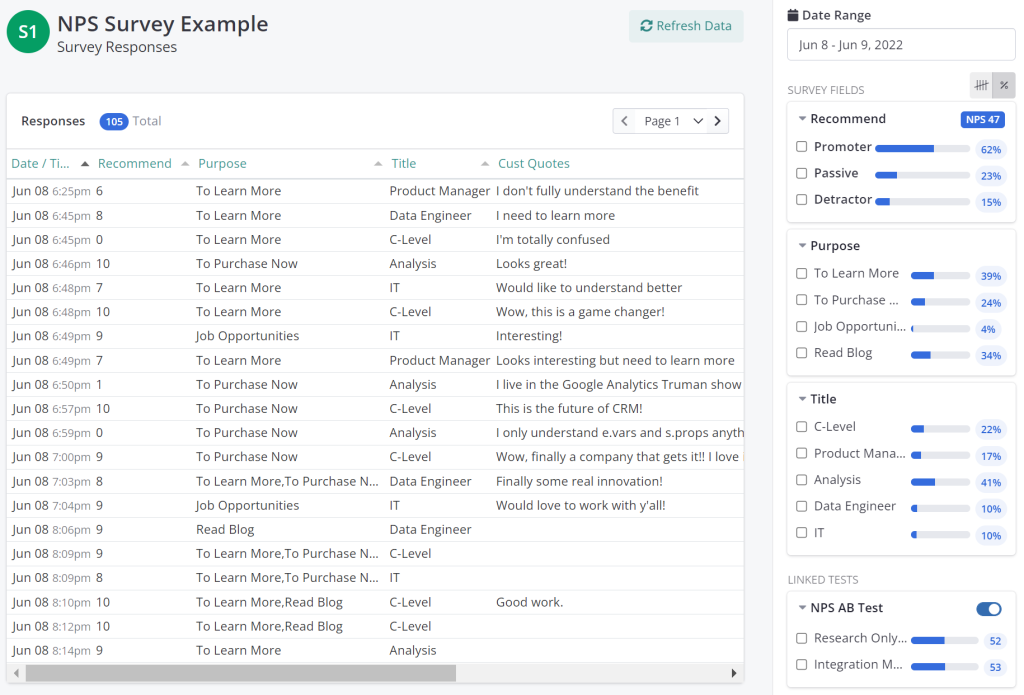

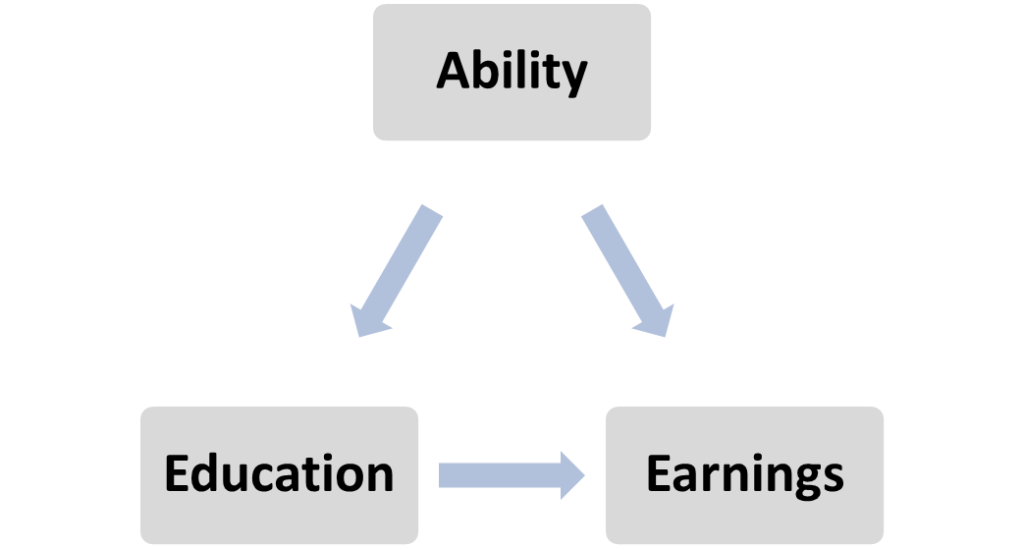

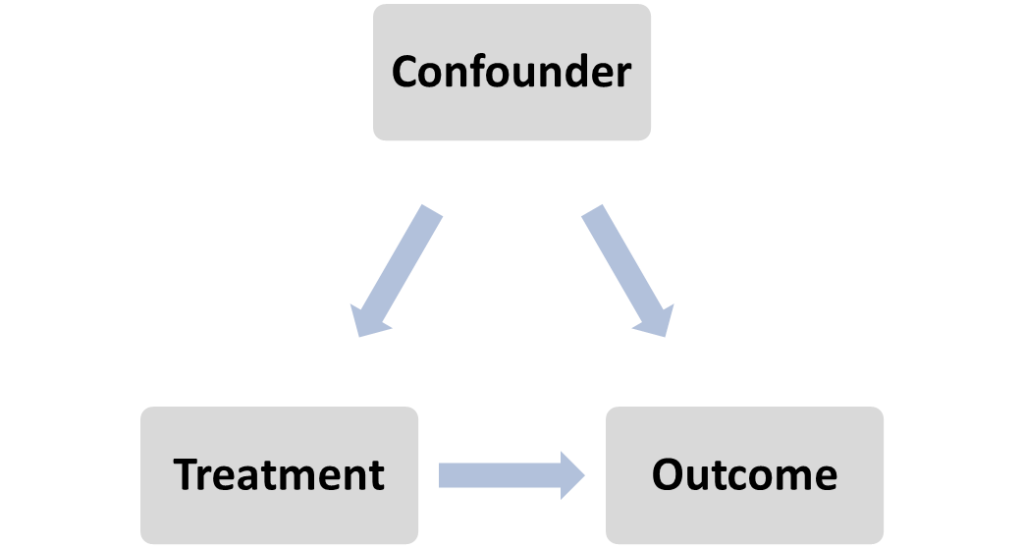

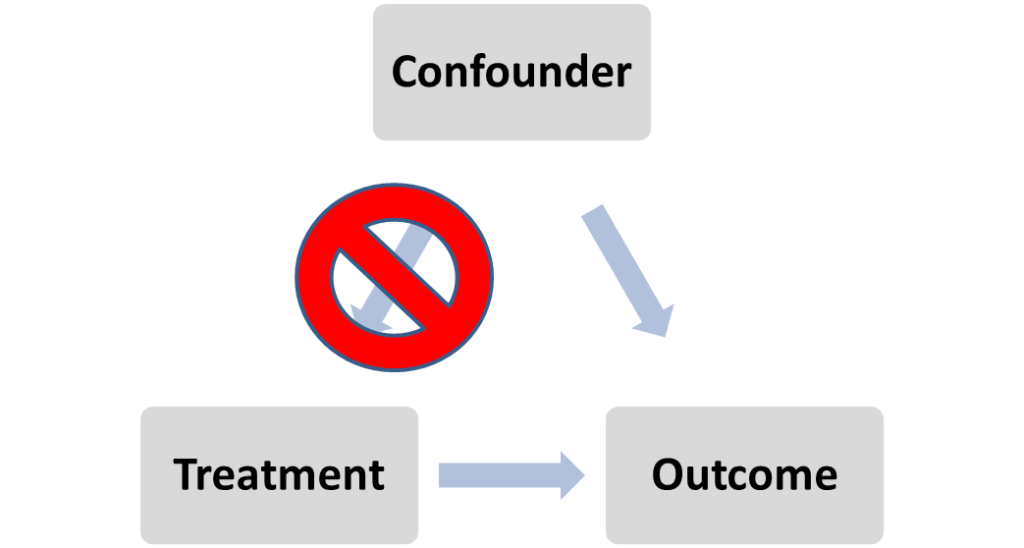

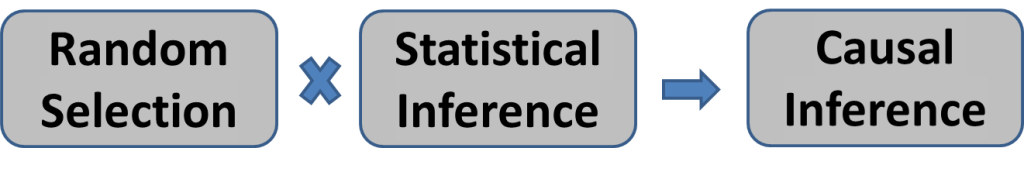

In 2022, we tackled ‘A/B testing: Cause, effect and uncertainty’. We reminded the room that seeing a pattern is not the same as proving a result. We focused on how to move beyond simple correlation to identify underlying cause-and-effect relationships, ensuring that, even as data becomes scarcer, our conclusions remain scientifically valid.

In our 2023 talk, we went a step further – not only providing the technical solutions, but also showing the values behind Conductrics. Building on the concept of Enlightened Hospitality by Danny Meyer, Matt discussed that the real goals of optimization are not to improve conversions, but to better serve the customer and, even in small ways, enrich their lives.

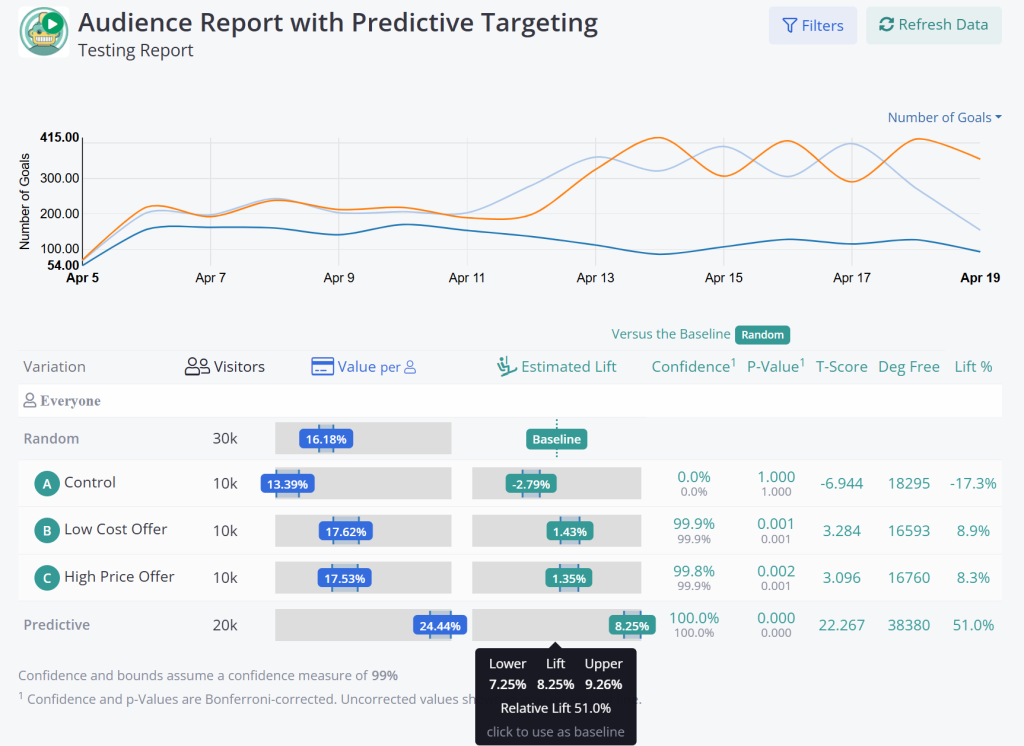

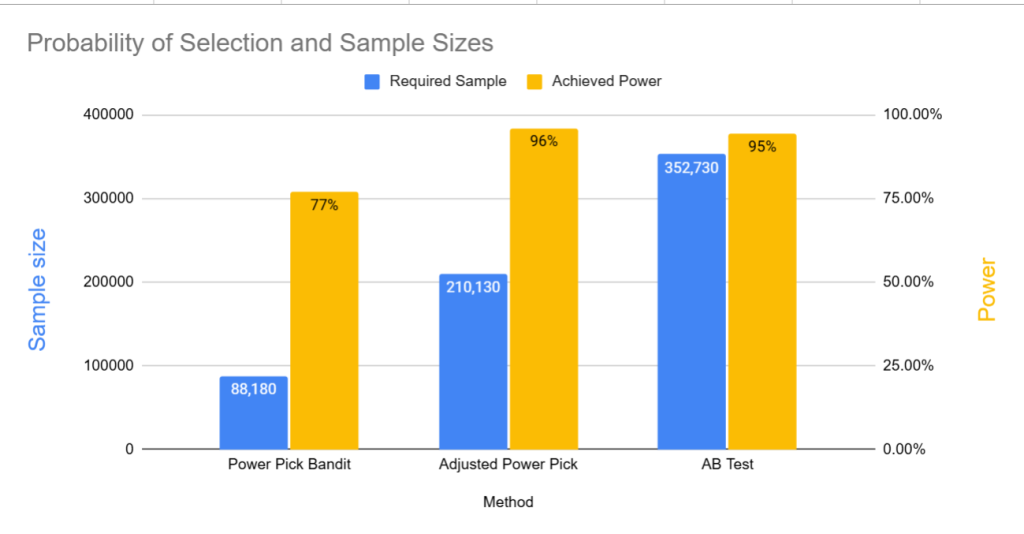

By 2024, as the cookie crumbled, we brought “Privacy engineering in analytics and A/B testing” to the Superweek stage. Even though the GDPR has been in force for years and the concept of data minimization has been discussed, the industry remained uncertain about how to work with less data, often viewing it as a disadvantage. We were there again, arming attendees with new options to make informed decisions. Finally, in 2025, Ezequiel Boehler, Solutions Architect at Conductrics, joined Matt on stage for “Bandits Bounce Back”, bringing a fresh perspective to the stage as we revisited one of our favorite topics.

More than just talks: Community over commerce

If the presentations are the brain of Superweek, the time spent between them is the heart.

Sponsoring Superweek for Conductrics is not about the logo on a lanyard. We sponsor it because it’s one of the few places that prioritizes community over commerce. It’s a “safe space” for data people – a snowy retreat where you can argue about attribution models at 2 AM by a fireplace, and where titles matter less than ideas.

“In a world filled with cynicism, Superweek Analytics Summit is about nothing if not about having total integrity. By being neither vendor nor agency Zoltán Bánóczy and Bernadett Király are able to put on one of, if not the only, conference in the world that is strictly for the attendees… No demos, no pitches… just providing a space for building relationships with other humans.”

— Matt Gershoff, Conductrics CEO, in his 2025 after-Superweek post

We try to contribute to that environment the best way we know how: by creating space for those relationships to form.

By now, the Conductrics Fireside Pub Quiz has become a tradition – we love being the catalyst that gets people talking. It serves as an ultimate icebreaker, lowering professional guards and turning a room full of attendees into a genuine community.

What we’re bringing to the bonfire in 2026

So, what does year 12 look like? We’re continuing to refine that essential mix of community and rigor. We are thrilled to confirm that the Fireside Pub Quiz is back on the agenda for Monday evening. And on the stage, we’re splitting our brain between the human and the machine.

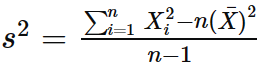

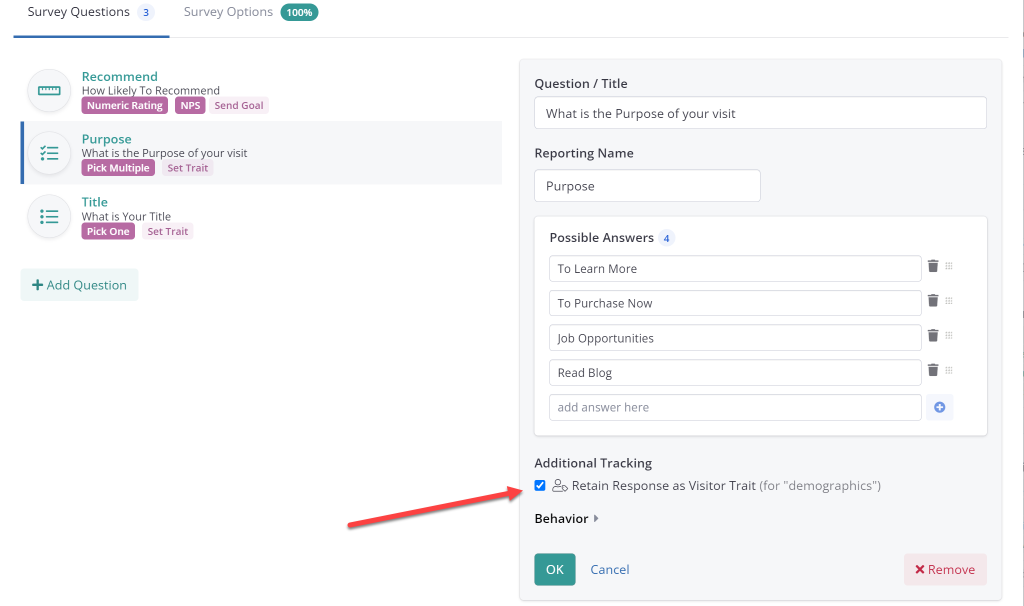

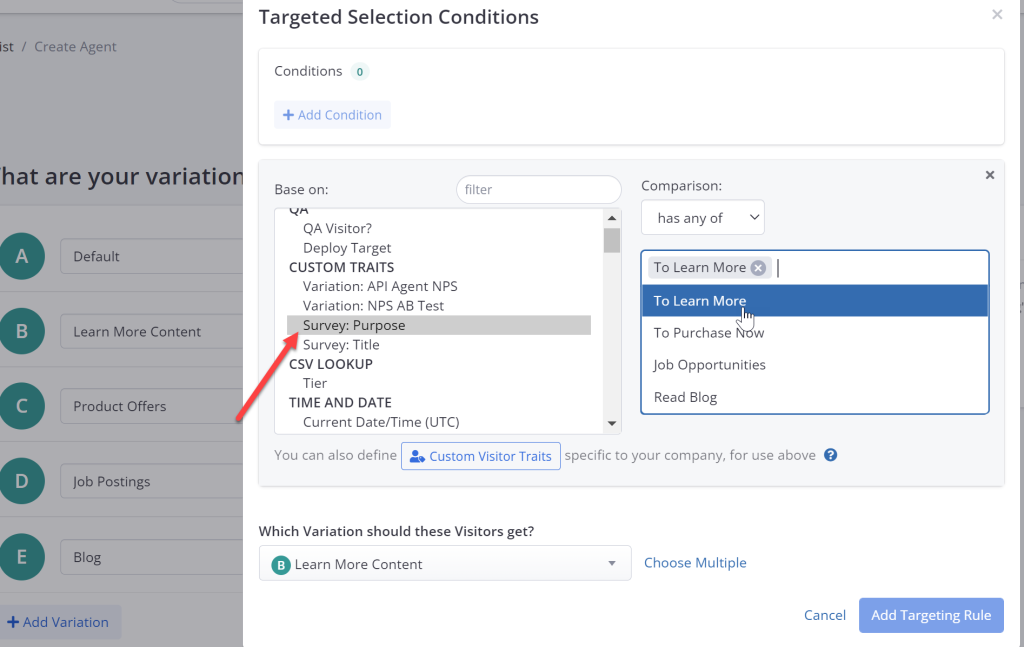

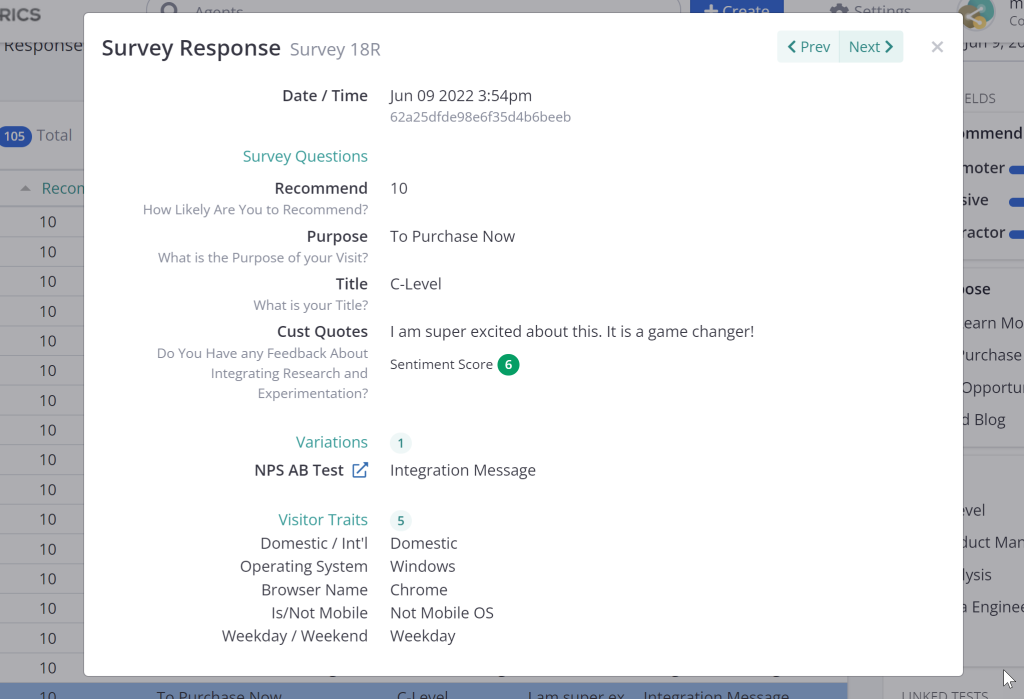

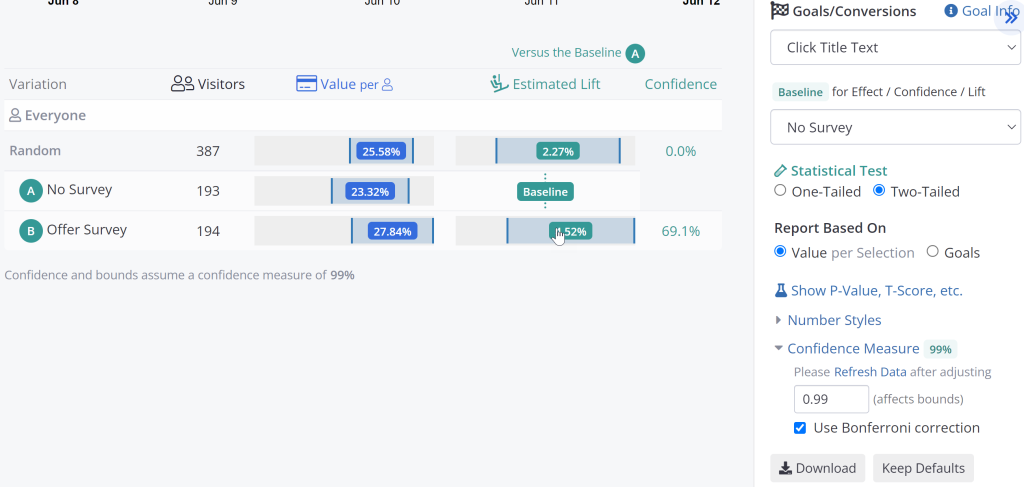

Ezequiel Boehler will tackle the human side in “Integrating Customer Feedback into the Optimization Flywheel.” We often get stuck thinking we need more sophisticated machine learning to solve our problems, when we would sometimes make more progress by asking our customers directly. Ezequiel will review how to blend customer feedback with A/B testing to get to the ‘Why” faster.

Meanwhile, Matt Gershoff is heading back to the statistical chalkboard with “Interactions: When 1 + 1 ~= 2.” If you’ve ever worried that your concurrent A/B tests are interfering with each other, or if the data actually supports targeting different experiences to different customer groups, this session is for you. It’s a straightforward look at how to model and answer the question: “Are there interactions?”

See you on the mountain

For us, Superweek is that rare ‘winning variation’ that just keeps getting better. It’s a unique environment where we can jump from the math of interaction effects to the warmth of human connection, all while sharing a s’more by the bonfire with the smartest people in the industry.

We’re proud to support it, excited to return, and we hope to see you there.