A long long time ago there was an RPG called “The End” which was set in a post-apocalyptic world. It’s hook was that the Rapture had happened, and all the truly good people were taken to heaven and all the truly bad people were taken to Hell, and the meek – the wishy-washy, uncommitted, cowards – inherited the earth. Since a lot of RPG nerds grow up immersed in American bible culture, some of them CREAMED THEIR JEANS over this “inversion” of the familiar Beatitude. But as I pointed out at the time, it didn’t mean anything. The setting was just another fight-for-scrap post-apoc setting. You didn’t even make up meek characters. The setting didn’t DO anything. It didn’t effect anything.

There’s an old Knights of the Dinner Table comic where the titular RPG crew have switched from fantasy to sci-fi, with the joke being that nothing has actually changed: the Hackmaster +12 sword is now just a Hackmaster lasersword, and fireballs are now flamethrowers. Very very slowly a variety of interesting, less mainstream titles (I won’t use the word indie, all RPGs are indie really) have nibbled around adding different structures but most of the time, if we’re in an avatar space we’re always going to end up having the same kind of stories. We have to! If you’ve got a band of uniquely talented individuals who need to constantly fall into plots that can be solved at least somewhat by violence, you end up telling the same kinds of stories, every single time. Huge seismic changes in the RPG hobby came from things like Call of Cthulhu, because there you had to investigate and go mad and die, and Vampire, because you actually had to talk to people in a society. Steve’s Second Law of RPGs goes that no matter how inventive your setting, I am probably going to be hired to protect a caravan or solve a mystery in my first scenario. The widow with goblins in her basement, the thieves robbing caravans, the low-level superheroes robbing the bank, these things always end up in most every RPG, which means setting means almost nothing.

You CAN do quite a bit, though, if you push on things well. You can make a standard fantasy setting and a group of PCs interesting, but to do it you have to make sure your setting elements have impact, at every level. World building isn’t just a bunch of ideas: it has to drive every single thing the players think about and do. The Shadow of the Demon Lord RPG by the great Rob Schwalb gets this. Although I want the forces to be stronger, the setting assumes you pick one of several apocalyptic scenarios that are rocking and wrecking the world the moment that play begins. The standard example is the orc rebellion. In the setting, the human empire conquered the half-giant vikings to the south, blasted them with dark magic and created a race of near immortal mindless killing machines called orcs. Except yesterday, all the magic wore off and every orc stopped being mindless. One of the orc generals stormed into the Emperor’s throne room, killed the Emperor, and took the throne. That’s a good example of a Big Thing that Effects Everything Else. Until yesterday, the empire was protected by orcs, now the orcs are in rebellion. Nobody can ignore that. You can run around the edges of it, but only for so long.

There’s an old rule of narrative building that a good way to start is with your villain. The thinking goes that in a lot of stories, the villain is the one with the chief amount of agency, so you need to figure out what things they want to exploit to achieve their evil plan, and what their weaknesses are, so you can then create a plausible way that a hero with everything against them can foil it. Building the villain first gives you the mold for the hero, so they perfectly fit. I think worldbuilding for games is best done the other way: you have to know what kind of heroes (or protagonists) you want, and what you want them to do, and then build the world to suit. It’s too easy to get it wrong the other way. Either your world won’t support heroes at all, so they become so aberrant it becomes weird (like trying to fit murderhobos into cosycore), or it will have things that are in the setting that don’t mean anything because they don’t connect to what the heroes are doing. The setting will be “Oh there are sixteen planes of genies who wished the world into existence and magic is a kind of fish…but you’re going to be defending a caravan, and/or solving a mystery, and most of you are detective ninjas”.

Superheroes tends to work well here because the comics have already been built around the idea of patrolling and dumb-ass villains doing stupid things that heroes can just stumble across. The setting was built around the needs of weekly comic book action. Fantasy less so, which is why it gets weird trying to map SEAL Team Six onto Lord of the Rings (which is why it was such a great moment when John Tynes said “just run it like SEAL Team Six, it works better that way”). Warhammer also has murderhoboing built into the setting: there are a class of mercenaries who wander around protecting caravans and fighting monsters, and that ecosystem is built into the setting. They have a place. The terrible option too many RPGs opt for is “the system is designed for you to be combat machines, but there’s a big sentence here that says you’re supposed to tell stories.” I flinch when I see “story first”. Fuck off with that. If you have to tell me to put story first, YOU HAVEN’T DESIGNED A GOOD ENOUGH GAME. The same goes for “don’t metagame”.

(Even worse, sometimes you’ll have games or game advice suggest that you punish players who make up murderhobos with dead relatives, as if they’ve been Naughty and have to be Shown How To Do It Right. Or they’ll suggest that only bad GMs create these kinds of players, and they are the Naughty ones.)

You do have to be a little careful though with how you build your world around your heroes or the action of the story. If it fits them too well and too snugly, it can make everything that isn’t connected to them seem less real (which means they might start killing the NPCs etc). It can also stretch believability and make things feel staged, or require players to suspend their disbelief a LOT. (“Yes there’s always a gang of the Joker’s thugs on a street corner in Gotham, waiting for him to always escape from Arkham, because that’s the rules of the story”.) Or the shape you create will be limited to only certain kinds of plots. It might do those well but it might work against you trying to do a slice of life drama or romance story in between. Players can also be pulled out of suspension of disbelief if they see too many of signs of the authorial stance (at which point they will probably conclude they want to just be authors). There’s only so many times you can Acquire Plot Points until you Trigger Act Three before setting also fades away – narrative structure was the caravan all along.

Of course, RPGs have it hard, being both a simulation of a believable, sandboxy world, where you can go anywhere and do anything, but also provide rich narrative. It’s no wonder then that we shrink the types of narratives down to suit simulations. There’s an old saying that RPGs tend to be wide, and provide tons and tons of options, so you can play them forever, or narrow, and thus really good for a brief encounter. With this rule there is often the suggestion that the former can tell any kind of story, and with the latter only one kind of story, but that’s not true, because the sandbox stories are all the same story. There’s just more stuffing around in the simulation parts. The narrative works the same way. So there are good reasons why we end up guarding caravans. The point is to be aware of this, not necessarily throw it away.

I’ve just written a book about worldbuilding and next week we launch a brand new world-creating game – The World Well – and both of them are about exploring the WHY of worldbuilding. They both start with the question: what is the world FOR? That’s what you need to know. Outside of the weird hobby where SF nerds build fake biospheres, worlds must have a purpose, and you should know what that purpose is, and you should make sure they achieve that purpose (and maybe even tell the players or at least the GM why the world is like that). It’s okay to say “there’s a bunch of clans in this setting because that makes for a good game, even though it’s not entirely realistic that this clan structure would exist in this context”. Like I said last week you should tell us why.

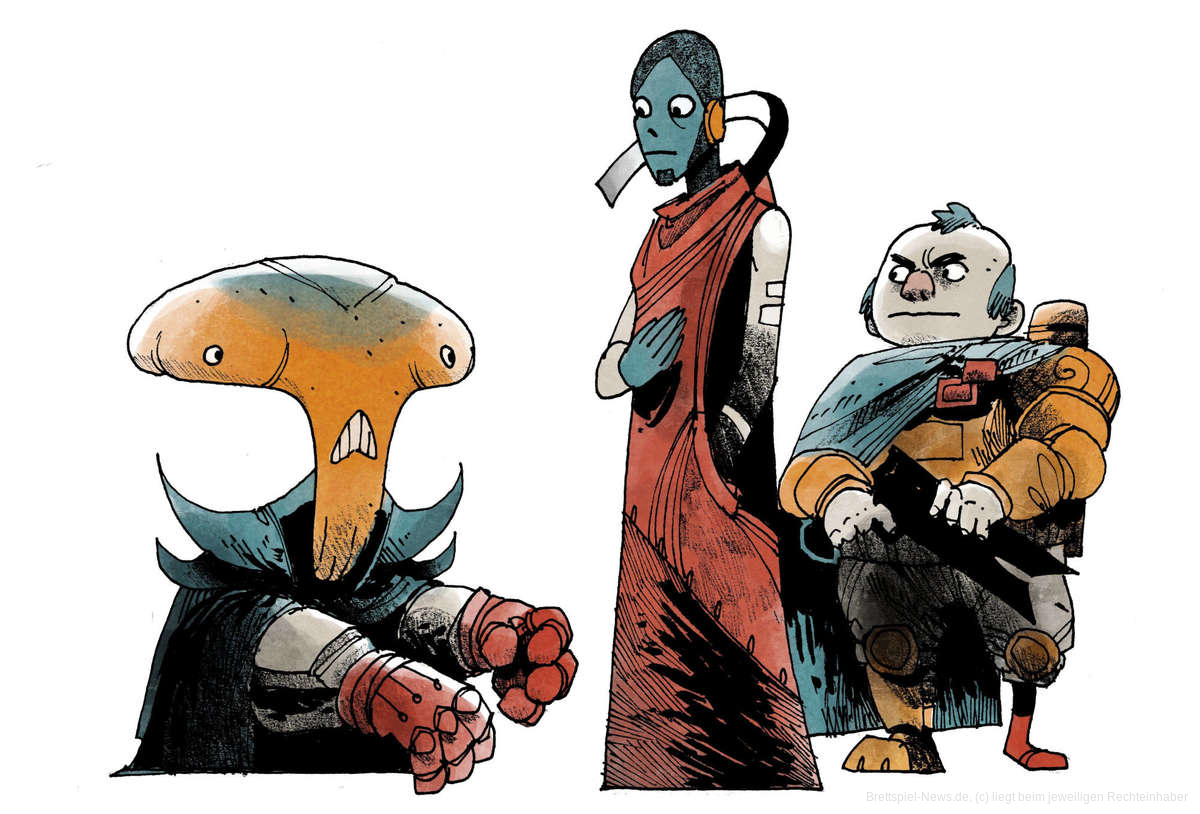

The World Well is built from the ground up to make a world riven with fractures, with contested factions fighting desperately over coveted power, exactly the things an RPG setting needs to give big exciting events and different points of view of the world. You may still, however, be protecting caravans. I can only do so much with groups of powered individuals fighting trouble. But at least the worlds you build will tremble as you do so. If that interests you, please go back it (and pre-order my book, too).