Yesterday I went to see Madame Tartuffe for the second time. It’s quite a play; I’ll get to that in a moment. But first: this morning I read, in The New York Times, an editorial by Angela Duckworth (an erstwhile champion of “grit”) about how “situational agency” is more effective than willpower in helping us achieve goals or change our habits. “Situational agency” comes down to setting up situations in your own favor: for instance, not owning a smartphone if you want to cut down on social media, or carrying water with you if you want to drink more of it. According to Duckworth, “research has shown” that such measures go farther in helping us achieve what we want.

Very well. But why does there have to be a single approach? Why does the article’s title (probably crafted by the editors) have to declare, “Willpower Doesn’t Work. This Does.”? And why does “research” speak with greater authority here than our own discernment?

First of all, it takes different sets of qualities, conditions, and actions to change habits and achieve things (although there’s overlap between the two). Both of them require a combination of actions and attitudes: yes, setting up the situation properly, but also making decisions, choices, and judgements in the moment, and using our experience and resources. Second, our goals change over time. Success does not always feel the way we expected it would. Something we strove for, as well as something we neglected, can change in meaning.

On Saturday I was debating whether to go hear the Bujdosó Quartet at the Három Holló in Budapest. This would have been in addition to a string of events over the coming days and would have required either returning home around 2:30 a.m. or paying for a hostel, staying overnight in Budapest, and spending the morning and early afternoon there before heading over to Madame Tartuffe and then a concert of Fiúk and 30Y at the Dürer Kert. Both of these options—returning home so late and staying overnight—felt excessive, so (with regrets) I ultimately decided not to go hear the Bujdosó Quartet this time. This required a certain amount of willpower (I was tempted to go and looked at various hostel options), along with a lot of reflection and a bit of what might be considered “situational agency” (sitting at my desk, where I have so many things to do). It may sound like a luxury decision anyway, except that it has to do with the larger endeavor of pacing myself, selecting events carefully, and keeping energy and time for my projects and life. In any case, it required a complex combination of thoughts and actions.

So does running (to a lesser extent). I have a basic routine, but in this very cold weather, and during the winter break, I have been starting out a little later than usual. Sometimes, in the early part of the run, I consider cutting it shorter than expected. Then I have to consider: is this my laziness speaking? Or is my body really tired? These days, 3.5 kilometers is my minimum, but various considerations go into the longer runs: a combination of pushing myself and trying not to overdo it. Even in the moment I have to decide what distance is appropriate for that day and then carry it out.

By heralding a single fix or approach, people can get book contracts, win followers, etc. But those single fixes tend to break down, even after helping up to a point.

Madame Tartuffe (a production of the Vígszínház, directed by Réka Kincses and performed at the Pesti Színház) is a comedy about a healing school based on a weird, vague single fix. Based loosely on Molière’s Tartuffe—the play emerged from the cast’s improvisations on this theme—it shows a young woman, Orgon (Andrea Petrik), and then her family, being drawn into the healing circle of the charismatic Barbara Tartuffe (played by the legendary Dorottya Udvaros), a graduate of a neuropathic school in Berlin, who cured herself of spinal problems and has now started her own therapeautic healing center (in the home of Orgon and her family). Central to the story is the internal agony of Orgon’s son, Damis (Ágoston Liber), who announces to his parents early on, at the dinner table, that he is a woman. Liber plays this with extraordinary reality, so that we believe the woman in him who finds herself in the group therapy sessions. One of the most poignant and disturbing moments is when Damis goes up to Tartuffe and gives her a grateful, appreciative hug. Another is the urine- and violence-spiked flirtation scene between Damis and Valér (Zsombor Kövesi), where Damis seems to be having pure, childlike fun.

What does Tartuffe’s group offer? Not some imported nonsense from the West; after the opening scene in Berlin, the play emphasizes its Hungarian setting. The group therapy seems to revolve around the premise (adorned with various slogans) that you can find yourself by physically releasing whatever is inside you. The primal scream is a must: even if you don’t think you have it in you, you can bring it out. The mind has little or nothing to do with it; you don’t really have to understand what’s going on with you, or what your responsibilities are. You just have to let it out. The proof is that you feel better afterward. (But are “feeling” better and “being” better the same?)

Tartuffe (who believes her own deceptions) cares little about those around her, despite the group hugs and tender words. She wants to radiate in her own and others’ eyes, to live forever. She sincerely, passionately believes in her own cures, because they have worked for her. Udvaros plays her with such energetic, magnetic comedy that you can fall for her manipulations along with each of the characters, including the hapless winemaker Pernelle (Ákos Kőszegi), whose transformation moves him so much that he proposes to help the group start a foundation. The whole plan unravels in unexpected ways, deceptions come undone, yet the therapy goes on. (Why? Because where there are lost people and people in pain, there will be cults and fads, including sincere ones.)

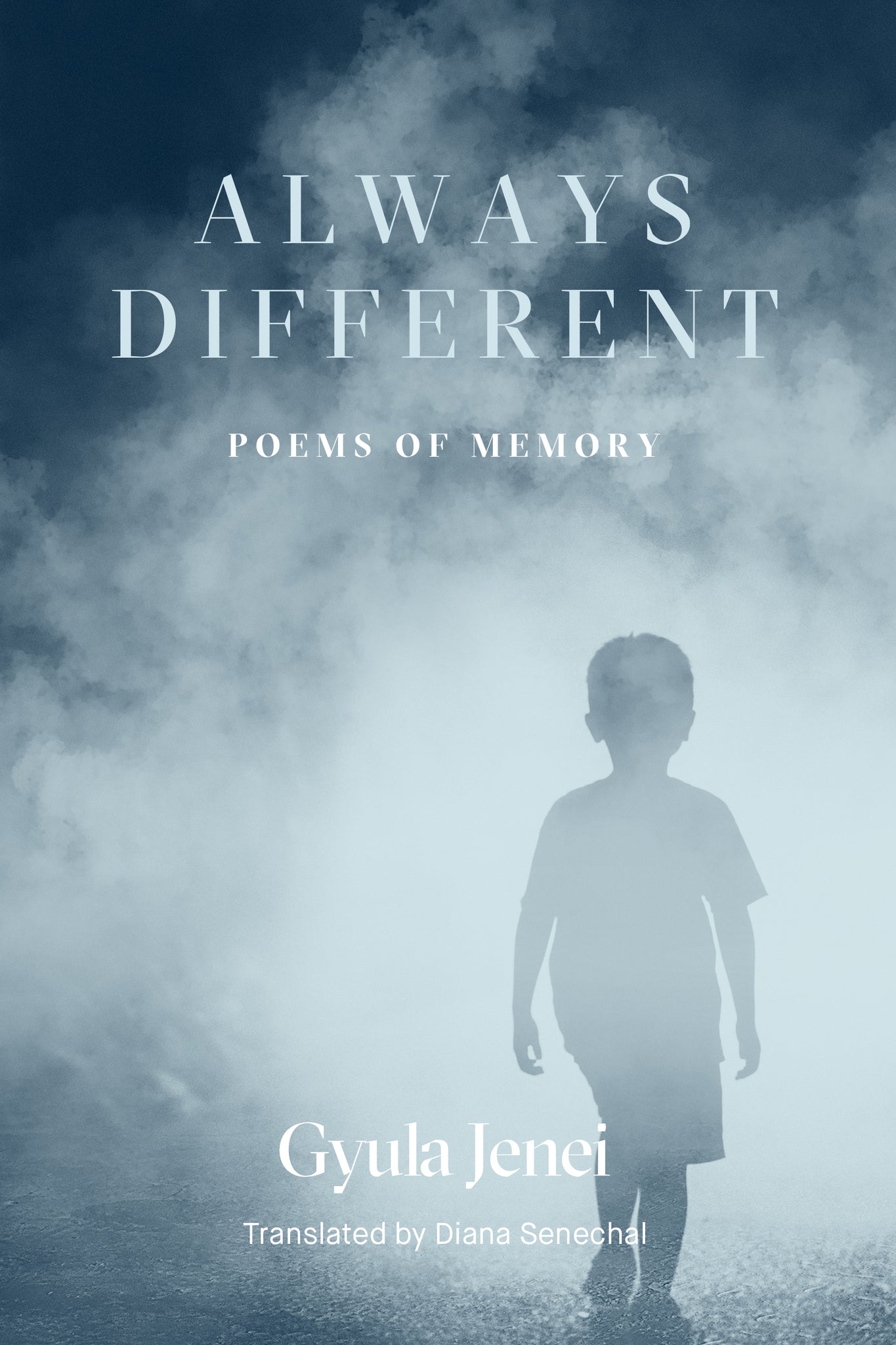

One scene in the play involves the audience; for this, people are encouraged to bring a stuffed animal. (Hence the photo at the top of this post.) Most people (of all ages) actually do; it’s quite a sight, all those stuffed animals of so many sizes, types, and colors. You might even feel slightly lonely without one. The first time I saw the play, I didn’t know to bring one; yesterday I forgot. I’d like to see it one more time (in a month or two); I’ll bring the pink stuffed octopus then. (I have only two stuffed animals: the octopus, given to me as a toy for my cats, and Suzy Bunny, a beloved family heirloom.)

Back to the question of single solutions: from what I have seen, most fads (political, therapeutic, educational, spiritual, financial, and otherwise) have to do with these. They propose One Thing that will make your life or the world better. That One Thing might even work in certain settings, for a little while. But precisely because we’re made of millions of elements (and exist in countless larger contexts), no fix in our lives is The Fix, no answer The Answer. I am glad.

I made a few edits to this piece after posting it.