Photo by Alicia Steels on Unsplash

What are the benefits and risks of participating in public media spaces?

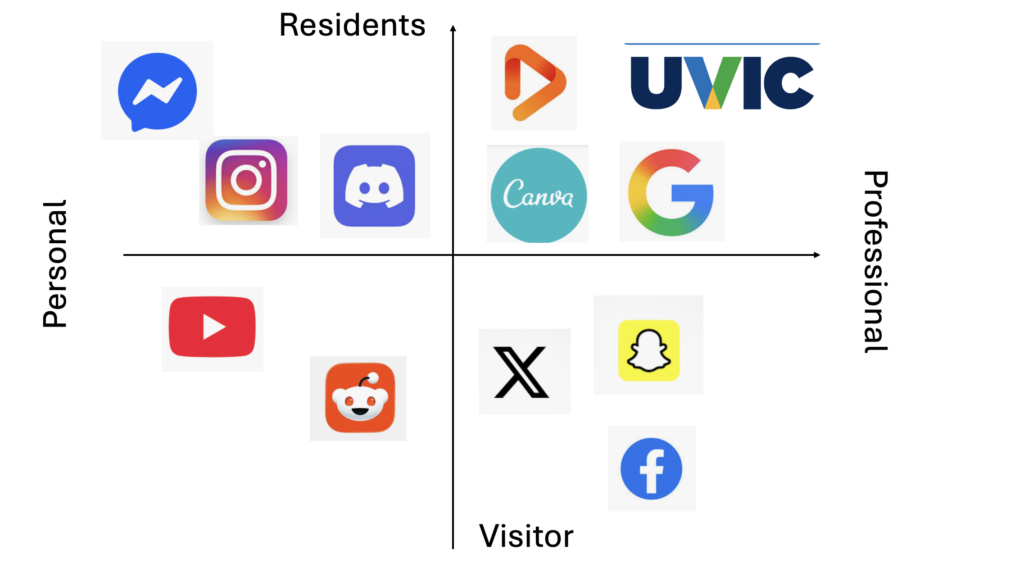

When I use my social media as a public professional learning network (PLN), I see it as both an opportunity and a risk. Public expression allows me to build a professional image, engage with diverse perspectives, and connect with various fields. I used to think digital literacy was just about knowing how to use technology. But after reading Trilling and Fadel (2009), I realized it also includes how we communicate online and judge information critically.

Furthermore, engaging in public media spaces enables continuous learning while also making me acutely aware that content spreads rapidly on social media. On social media, even one sentence can spread very fast. People might screenshot it or misunderstand what you meant. As Hirst (2018) notes, the social news environment is influenced by algorithms and business models, often amplifying emotional content.

For instance, many Chinese bloggers repost social news, such as videos of the Shanghai conflict incident. Initially, everyone was emotionally charged, but days later, when the police released their official statement, it became clear that the bloggers’ information was incomplete and even partially misleading. While those who reposted earlier may not have acted maliciously, they contributed to the spread of emotion—a scenario not uncommon on Weibo.

Conflict and Responses in Public Discourse and the Challenges of Media Literacy

On public platforms, facing criticism is actually quite normal, especially when discussions involve social issues or factual judgments, which are more likely to spark debate. I believe media literacy leads to conflict because it doesn’t just involve debating the truthfulness of information; it also touches on personal stances and beliefs.

When we question the source of a piece of information, the other party may feel their viewpoint is being dismissed. Social media algorithms also make this worse. They show us content we already agree with, so over time different groups see very different versions of reality.

Hirst (2018), in discussing fake news, noted that the spread of misinformation relates to media structures and commercial mechanisms. I’ve observed that some conflicts aren’t merely personal disagreements but outcomes shaped by broader environmental influences.

Against this backdrop, I believe responding to negative comments requires even greater rationality. Instead of emotional counterattacks, we should choose to provide evidence, explain our positions, or opt not to reply when necessary. Trilling and Fadel (2009) highlight critical thinking and responsible communication as components of digital literacy, describing how we evaluate information and navigate disagreements.

For instance, many public figures on China’s Weibo have faced intense criticism over a single statement, only to later clarify that their words were taken out of context or maliciously interpreted. Comment sections often become spaces where certain groups form fixed opinions, with few willing to revisit the original context. This “emotion-first” environment inherently makes rational discussion difficult.

This feels even more important for people who have a professional identity, because others might see their words as representing an organization, not just themselves. For me, maintaining composure during conflicts is more important than “winning the argument.” It’s crucial to express oneself rationally in public spaces and respect differing opinions.

Reference:

Trilling, B., & Fadel, C. (2009). 21st century skills: Learning for life in our times. Jossey-Bass.

Hirst, M. (2018). Navigating social journalism: A handbook for media literacy and citizen journalism. Routledge.