Tidöregeringen sminkar friskolegrisen

19 Jan, 2026 at 16:30 | Posted in Education & School | Leave a comment Tidöregeringen har i dagarna enats om att — i enlighet med den gängse offentlighetsprincipen — lägga fram ett lagförslag om full insyn i fristående skolor.

Tidöregeringen har i dagarna enats om att — i enlighet med den gängse offentlighetsprincipen — lägga fram ett lagförslag om full insyn i fristående skolor.

Som om detta skulle lösa det grundläggande problemet med friskolorna!

Ingalunda.

Ett flertal undersökningar har på senare år visat att det system vi har i Sverige med vinstdrivande skolor leder till att våra skolor blir allt mindre likvärdiga — och att detta i sin tur bidrar till allt sämre resultat. Ska vi råda bot på detta måste vi ha ett skolsystem som inte bygger på ett marknadsmässigt konkurrenstänk där skolor istället för att utbilda främst ägnar sig åt att ragga elever och skolpeng, utan drivs som icke-vinstdrivna verksamheter med kvalitet och ett klart och tydligt samhällsuppdrag och elevernas bästa för ögonen.

Vi vet idag att friskolor driver på olika former av etnisk och social segregation, påfallande ofta har låg lärartäthet och i grund och botten sviker resurssvaga elever. Att dessa verksamheter ska premieras med att få plocka ut vinster på våra skattepengar är djupt stötande.

I ett samhälle präglat av jämlikhet, solidaritet och demokrati borde det vara självklart att skattefinansierade skolor inte ska få drivas med vinst, segregation eller religiös indoktrinering som främsta affärsidé!

Till skillnad från i alla andra länder i världen har den politiska ledningen i vårt land gjort det möjligt för privata företag att göra vinst på offentligt finansierad undervisning. Och detta trots att det hela tiden funnits ett starkt folkligt motstånd mot att släppa in vinstsyftande privata företag i välfärdssektorn.

Att införa friskolor var ett av de största fel som någonsin begåtts i svensk skolhistoria.

Och det rättar vi inte till med att sminka grisen med en tamlös insynsåtgård!

Swedish Institutionalism

18 Jan, 2026 at 20:16 | Posted in Economics | 1 CommentIn recent times, there has been a growing interest in institutionalist trends and research within economics. Traditional explanations and analyses have seemed to have little or no value. Abstract and unrealistic theories have increasingly been replaced by historically grounded ones. Institutional and structural elements in the economy are highlighted, replacing overly short-term and model-based variables. It is, therefore, not surprising that economists have become interested in theories with a strong economic-historical perspective, where the starting points for understanding the dynamic development, transformation, and inertia of the economy differ from those in traditional neoclassical economic theory.

Johan Åkerman (1896-1982), who worked in Lund, Sweden, developed one such theory. Far from the centres of power and economic policy engineering, he devoted himself to the long-term and underlying aspects of economic development.

Johan Åkerman (1896-1982), who worked in Lund, Sweden, developed one such theory. Far from the centres of power and economic policy engineering, he devoted himself to the long-term and underlying aspects of economic development.

Like his American counterparts, Åkerman aimed to build a new economic theory with evolutionary and institutional features. His main interest until the beginning of the 1930s was empirical business cycle research. After that, his work expanded to include methodological and epistemological studies where he sought to surpass the narrow confines set by the neoclassical tradition in economics, as he perceived them. During the post-war period, he actively participated in debates on education and research policies and wrote articles on topics like international politics.

In his dissertation — Om det ekonomiska livets rytmik (1928) — Åkerman sets out to synthesize theoretical and statistical analyses of the problems of business cycle fluctuations. His primary focus is on understanding the relationships between different variations — seasonal, cyclical, and secular. What sets Åkerman apart is primarily the proposition that seasonal variations form the basis for the formation of business cycle fluctuations.

Åkerman also attempts to describe the difference between what he calls equilibrium economics and time economics. While equilibrium economics tries to avoid the problem of causation by ignoring time, time economics seeks to start from reality and the causal relationships that apply there, even if this means that the laws formulated cannot be as general as those of equilibrium economics; they become time-specific and only apply to a certain economic period. Time represents a distinct dimension, whose inclusion in the analysis must modify the entire established theoretical system. Åkerman believed that the conventional theory’s incorporation of the risk aspect to accommodate variability and dynamism in equilibrium economic analysis is reminiscent of “the baker’s apprentice who forgot to add yeast to the dough and, therefore, threw it into the oven afterwards.”

For Åkerman, attempts to bridge the gap between neoclassical analysis and a truly evolutionary and change-oriented time-economic analysis are epistemologically impossible. A completely new approach to economic analysis is necessary. In a dynamic analysis, one must grasp the process as having evolutionary elements. To interpret evolutionary phenomena, the questions must be grouped in a way that the driving forces clearly emerge. To achieve this, Åkerman divides societies into X and Y types.

The X-society corresponds to the orthodox economists’ free-market society. The direct opposite of the X-society is the Y-society, the fully implemented planned economy. The real society is always an XY-society, with elements from both model societies.

Åkerman argues that it is important to distinguish between what he calls causal analysis and calculation analysis. Causal analysis is “an objective and, if possible, quantitative reconstruction of the actual events,” while calculation analysis is “logical rationalizations of the calculating actions of individuals.” Every economic theory contains elements of both. The problem often lies in their confusion.

When Åkerman examines the existing economic schools, he can conclude that their differences can be attributed to their treatment of the reality- and summation problem. The former concerns the relationship between reality and the concepts with which we try to analyze and understand it. The summation problem concerns the relationship between the micro and macro levels of analysis. Normally in neoclassical economic theory, it is assumed that the whole (macro) is a simple sum of its parts (micro), which Åkerman views as a “victory of form over content.” Identity statements take precedence over causal analysis, and the relationship between different groups’ activities and the macroeconomy is “magically eliminated” with summation symbols.

The core of causal analysis lies in the study of structural transformation, in which Åkerman hopes to trace the most crucial elements of cumulative causality through systematic shifts in activity periods and demonstrate the power shifts that are decisive for the institutional transformation that necessitates the continuous change of economic theory.

In his magnum opus, Ekonomisk teori (Part I 1939, Part II 1942), Åkerman builds a synthesis of his early presentations and applies his theories to a large empirical material. In the concluding part of the first book, he discusses the central concept of structure. All the economic principles addressed in economics are actually conditioned by structure and strictly applicable only as long as this structure exists. The concept of economic structure is relativistic in nature. By designating a particular structure’s position relative to preceding and subsequent structures, the concept becomes primarily a tool for seeking the forces that govern structural changes.

Johan Åkerman was a highly original and distinctive economist. His methodological and theoretical works displayed rare sharpness and depth. In the early stages of his career, he primarily focused on empirical business cycle research. However, his own contributions in this area were characterized by a desire to broaden the boundaries of economic theory. Like Wicksell, he was interested in understanding business cycles as cumulative non-equilibrium processes, and similar to Schumpeter and the institutionalists (Veblen, Commons, Mitchell), he emphasized evolution and transformation, rather than equilibrium and static states.

Alongside John Hobson, Johan Åkerman is one of the most significant European institutionalists before World War II. His holistic approach permeated much of his work, as did his emphasis on imbalances, non-equilibrium, and conflicts between different groups in society. He attached great importance to the use of inductive methods. Like Mitchell, Åkerman eventually expanded his business cycle theories to encompass broader socio-economic analyses. His treatment of the reality and summation problem also demonstrates how critical he was of the neoclassical economists’ deductive constructions built around the concept of the ‘economic man.’

Åkerman shares many of the institutionalists’ views, but his concept of institutions is somewhat narrower than that of his American counterparts. Often, he equates institutions with power. In general, Åkerman tends to reduce the institutional analysis to a question of power among different groups in society, which is quite different from the broader analysis conducted by the American institutionalists.

Åkerman wanted to replace what he perceived as poorly substantiated calculation analyses prevalent in the existing theory with a causal analysis centred around a real understanding of reconstructed actual historical processes. Instead of analyses based on aggregate concepts, he advocated for an analysis of transformation processes built on disaggregated units such as groups and driving forces. According to Åkerman, achieving this required a broad social science synthesis that adequately incorporates changing structures and institutions in the analysis. This is what he sought to accomplish with his institutionalism.

Problemen med centralbankers ‘oberoende’

17 Jan, 2026 at 10:38 | Posted in Economics | 6 Comments

När riksdagen 1998 beslutade om ändringar i regeringsformen och riksbankslagen gjorde man Riksbanken formellt och konstitutionellt oberoende från regering och riksdag i penningpolitiska beslut.

Tanken var att man beslutsmässigt skulle ha mer eller mindre vattentäta skott mellan finans-och penningpolitik. Detta har också inneburit att Riksbanken har en nästintill oinskränkt makt över en politik som i hög grad styr inflation, sysselsättning och ekonomisk stabilitet. Denna makt bör vara föremål för större demokratisk övervakning för att säkerställa att den överensstämmer med vad vi som samhällsmedborgare har för intressen.

När man diskuterat Riksbankens oberoende har man oftast definierat detta i förhållande till regeringar och intressegrupper. Men hur är det med finansmarknaderna? Hur oberoende är centralbankerna från påtryckningar från finansmarknadernas aktörer? Utifrån vad vi sett hur Riksbanken agerat de senaste decennierna kan man bara konstatera att oberoendet mest kommit att gälla gentemot finanspolitiken och att de åtgärder Riksbanken vidtagit mest har tillgodosett finansmarknadernas intressen.

Riksbanken har över tid utvecklat en slags ‘policybias’ där inflationskontroll prioriteras över arbetslöshet och välfärd, vilket för breda samhällsgrupper framstår som djupt stötande.

Om vi i ett grundlagsenligt och demokratiskt fattat beslutat kommer fram till att vi i stället för ett givet inflationsmål vill prioritera rättvisa, välfärd och jobb, är det svårt att se varför vi ska var bundna av en institution som påtvingar oss ett mer utrerat ‘ekonomistiskt’ val via ett regelverk som är konstruerat med just det syftet. Vi får inte glömma att ekonomi INTE alltid är ett trumfkort i policyfrågor. Detta borde egentligen vara självklart, men inte minst ekonomer har lätt för att glömma det. Utifrån ett ‘ekonomistiskt’ perspektiv kan man säkert t. ex. hävda att det samhällsekonomiskt är mer lönsamt att återinföra ättestupan än att bygga ut en dyr äldrevård. Men vem skulle på fullt allvar förespråka eller acceptera något sådant? Andra aspekter väger ibland tyngre än rent ekonomiska.

Utöver problemen med ‘demokratiaspekter’ på Riksbankens självständighet finns det nog också — speciellt utifrån de senaste två decenniernas uppseendeväckande misslyckanden att uppnå inflationsmålen — goda skäl att ifrågasätta Riksbankens kompetens. Internationell forskning har också övertygande visat att den empiriska evidensen för argumentet att självständiga centralbanker skulle vara av godo för ekonomin, är nästintill obefintlig.

För alla som är naiva nog att tro att centralbankschefers arbete bygger på gediget evidensbaserad vetenskap — glöm det. Som dokumentären Skuldfeber dokumenterar på ett övertygande sätt, är centralbankschefers arbete inte mycket mer än subtilt sagoberättande bondfångeri — vilket de själva medger!

Mathematics and Enlightenment

16 Jan, 2026 at 19:51 | Posted in Theory of Science & Methodology | 2 Comments

When in mathematics the unknown becomes the unknown quantity in an equation, it is made into something long familiar before any value has been assigned. Nature, before and after quantum theory, is what can be registered mathematically; even what cannot be assimilated, the insoluble and irrational, is fenced in by mathematical theorems. In the preemptive identification of the thoroughly mathematized world with truth, enlightenment believes itself safe from the return of the mythical. It equates thought with mathematics. The latter is thereby cut loose, as it were, turned into an absolute authority …

The reduction of thought to a mathematical apparatus condemns the world to be its own measure. What appears as the triumph of subjectivity, the subjection of all existing things to logical formalism, is bought with the obedient subordination of reason to what is immediately at hand. To grasp existing things as such, not merely to note their abstract spatial-temporal relationships, by which they can then be seized, but, on the contrary, to think of them as surface, as mediated conceptual moments which are only fulfilled by revealing their social, historical, and human meaning—this whole aspiration of knowledge is abandoned. Knowledge does not consist in mere perception, classification, and calculation but precisely in the determining negation of whatever is directly at hand. Instead of such negation, mathematical formalism, whose medium, number, is the most abstract form of the immediate, arrests thought at mere immediacy. The actual is validated, knowledge confines itself to repeating it, thought makes itself mere tautology. The more completely the machinery of thought subjugates existence, the more blindly it is satisfied with reproducing it. Enlightenment thereby regresses to the mythology it has never been able to escape …

The subsumption of the actual, whether under mythical prehistory or under mathematical formalism, the symbolic relating of the present to the mythical event in the rite or to the abstract category in science, makes the new appear as something predetermined which therefore is really the old. It is not existence that is without hope, but knowledge which appropriates and perpetuates existence as a schema in the pictorial or mathematical symbol.

The most-read blog post in 2025

14 Jan, 2026 at 18:04 | Posted in Economics | Leave a commentMy blog post, Sweden’s unequal wealth distribution, was the most-read post on Real-World Economics Review (RWER) in 2025.

I am, of course, truly awed, honoured, and delighted!

For the benefit of those who haven’t read it, I am reposting it here:

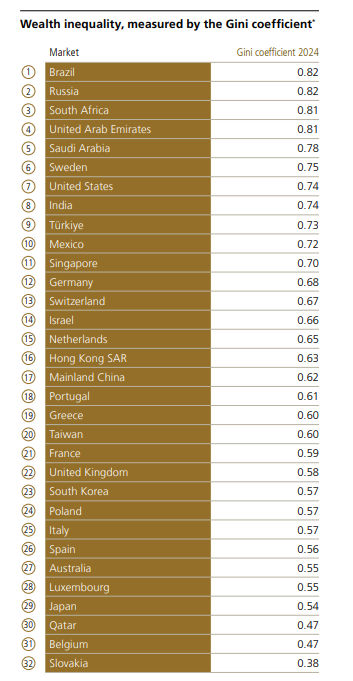

UBS Global Wealth Report 2025 reveals that Sweden — once a global beacon of equality — has now fallen to the far less enviable position of sixth place among the world’s most unequal countries in terms of wealth.

UBS Global Wealth Report 2025 reveals that Sweden — once a global beacon of equality — has now fallen to the far less enviable position of sixth place among the world’s most unequal countries in terms of wealth.

How could things have gone so wrong for a country that, not so long ago, was seen as a model of equality?

Almost a decade ago, Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century hit the shelves. In many ways, it marked a turning point in the global conversation about economic inequality. But last year, Swedish economics professor Daniel Waldenström, of the Research Institute of Industrial Economics (which is controlled by the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise, an employers’ organisation and an interest group for Swedish business), published the book Superrika och jämlika: Hur kapital och ägande lyfter alla (Super-Rich and Equal: How Capital and Ownership Lift Everyone), arguing that Piketty is fundamentally wrong about the trajectory of wealth inequality.

Waldenström’s case hinges on shifting the time frame. Instead of focusing mainly on the past 40 years — as Piketty does — he stretches the analysis over 130 years. The result, he claims, is a far more optimistic story: although the number of super-rich Swedes has risen, inequality has not. In fact, he insists that wealth has never been more evenly distributed. Why? Because (1) Swedes today are, on average, 30 times richer than in the late 19th century, (2) much of that wealth now comes from housing and pension savings, and (3) this has broadly levelled out wealth distribution, even though the richest 1% have pulled ahead in recent decades.

Piketty attributed the long decline in wealth inequality during the 20th century largely to the upheavals of the two world wars and the rise in capital taxation. Waldenström disagrees. He points instead to institutional changes — universal suffrage and expanded education — as the key drivers, since these raised wages and made widespread saving in housing and pensions possible.

But Waldenström doesn’t stop at describing what he sees as the historical trend. His book also dishes out advice — to policymakers and individuals — on how to tackle inequality. Unsurprisingly, that advice is steeped in a distinctly conservative worldview.

Take housing. Many of us have long thought Sweden’s housing policy has tilted far too much toward promoting private ownership at the expense of affordable rental housing. The politically driven conversion of rental units into condominiums has left vulnerable groups struggling to find reasonable housing. Waldenström, however, says we should double down — pushing even harder for condominiums and owner-occupied flats. In his view, only when households own their homes will buildings be properly maintained. Rising house prices and the growing number of outright homeowners? Purely positive, in his book. That this has also made Swedes one of the most indebted peoples in the world, he waves away, insisting we should measure debt not against disposable income but against asset values. Mirabile dictu!

It’s striking how unequivocally Waldenström treats pension funds and privately owned homes as clear markers of wealth equality. Ask today’s young people—forced to borrow millions just to get on the housing ladder — whether they feel like winners in this supposed game of equality. The same goes for pensioners. Locked-away pension assets don’t feel like the same kind of wealth as stocks or other liquid holdings.

On taxes, Waldenström wants income taxes cut—hardly a novel proposal from the political right, and one that could in theory appeal more broadly if it meant targeted relief for the lowest earners alongside higher taxes on top incomes and capital. But that’s not on his radar. The real problem, in his view, isn’t that capital is undertaxed—it’s that higher taxes might dampen the “incentives” of the country’s “successful owner families and entrepreneurs” to innovate and create jobs.

When it comes to whether extreme wealth concentration poses a threat to democracy, Waldenström again sees no real issue. Many — after watching the antics of Elon Musk, for example — would beg to differ. For him, the solution is not to “curb wealth” but to “strengthen the integrity of the political system.” A more naïve reading of the link between money and power would be hard to imagine.

Much of Waldenström’s argument — that inequality has declined — rests on comparing today’s Sweden to the late 19th century. And sure — no one disputes that Sweden is more equal and wealthier now than when a single person could hold a majority of votes in a local parish. But that’s not the point. Critics of Sweden’s neoliberal turn since the 1980s have focused on the rise in inequality within our lifetimes. And here the facts are clear: for the past 40 years, it’s been getting worse. Telling people that “things were even worse 130 years ago” is like telling the unemployed today not to complain because joblessness was higher in the 1930s. Few will be persuaded.

The LO’s (Swedish Trade Union Confederation) latest report, The Power Elite: Rocketing Away from Reality, shows that corporate executive pay continues to skyrocket, reaching historic highs. In 2023, the CEOs of Sweden’s 50 largest firms earned, on average, more than 70 times what an industrial worker makes. For Waldenström, this is not a problem. On Swedish television’s news program Rapport, he commented that “as long as one simply discusses and lands [sic!] at both the CEO level and other employees’ level, it becomes the wage that is reasonable to bear.”

What can one say about this belt-and-suspenders defence of inequality? Backed by business-sector funding, Waldenström is trying to whitewash the vast disparities in Sweden today. But it doesn’t work.

The top 10% of earners now control the same share of disposable income as roughly the bottom 50% combined. Sweden has the second-highest wealth concentration in the EU. The idea that this is not a democratic problem is one that very few serious social scientists would endorse.

Waldenström’s book reveals a once-serious researcher who has chosen to become one of the loudest market-apologetic megaphones for Swedish big business — offering analyses that are little more than ideologically tinted whitewashing of serious social problems.

Mainstream economists over and over again tell us that inequality isn’t really a problem at all, because the gap between top and bottom will always be greater in a successful economy. This line of reasoning is a familiar refrain among market fundamentalists. It’s the old “trickle down theory”: feed the horse more oats, and eventually enough will pass through to feed the birds.

The problem is that the empirical evidence for this “trickle down” is precisely zero.

Several concurrent reports from autumn 2025 indicate that 700,000 Swedes are living in poverty. This represents a doubling since 2021, bringing the figure to nearly 7% of the population. The issue encompasses both social and material deprivation, with many unable to cover even the most basic expenses.

All economics is politics. All economics is power. Sweden has the second-highest concentration of wealth in the EU. The claim that this does not constitute a democratic problem is one shared by very few serious social scientists.

Postmodernism — a severe case of anti-intellectual mumbojumbo

14 Jan, 2026 at 14:42 | Posted in Politics & Society | 1 Comment

That postmodern phrases bounce around the academic world like passwords at seminars and such does not, in itself, matter much — beyond the irritation they cause. The real damage begins when those phrases start to erode the seriousness and rigour of scholarly historical work …

If researchers within the scientific community themselves dissolve the boundary between individual and world, between observer and the observed, between fiction and knowledge, they not only make their own internal discourse less meaningful — if not meaningless — but also risk eroding the support they have so far been able to count on from citizens in the surrounding society. For why should these citizens contribute tax money to an enterprise whose representatives openly declare that they themselves do not believe in the possibilities of science? Why indeed?

While the most immediate threats to science today stem from short-sighted politicians slashing research budgets, we must not overlook the corrosive influence of postmodernist academia. Postmodernist thought that trades in radical posturing while peddling glib, unserious analysis diverts attention from the urgent task of building a rigorous, evidence-based social critique. The Enlightenment project — with its commitment to empirical truth, reasoned debate, and the relentless testing of ideas against reality — remains indispensable. Without these foundations, progressive criticism collapses into demagoguery or empty intellectual trends.

Postmodernism’s allure lies in its veneer of subversiveness, but its actual effect is to paralyse critical thought. By recasting objectivity as an illusion and truth as a mere social construct, it leads well-intentioned scholars into dead ends: relativistic word games, and fashions that prioritise ‘cleverness’ over clarity. Worse, it actively undermines the possibility of a coherent progressive politics. How can we challenge power structures if we dismiss the very tools needed to analyse them — facts, logic, and evidence?

Many scholars who embrace postmodernism, social constructivism, and poststructuralist relativism consider themselves part of the political left. There is no inherent flaw in research guided by political commitments. Yet no matter our personal political sympathies — as scientists, academics, or engaged citizens — we must resist letting ideology distort intellectual rigour. Simply adopting the language of radical critique does not equate to meaningful political engagement.

The allure of ‘deconstructing’ truth, dismissing objectivity, and reducing knowledge to power struggles may seem subversive, but in practice, it often leads to intellectual dead ends. Slogans dressed up as theory, fashionable jargon masquerading as insight, and a reflexive scepticism toward evidence do nothing to advance concrete social change. Worse, they divert energy from the hard work of building a substantive progressive politics — one grounded in empirical reality, logical coherence, and actionable analysis.

Genuine radicalism requires more than contrarian posturing. If the left is to offer a compelling alternative to entrenched power structures, it cannot rely on obscurantist thinking or relativistic platitudes. Social progress depends on our ability to distinguish fact from fiction, to marshal evidence in the pursuit of justice, and to articulate a vision of a better society that is both critical and coherent. Postmodern nonsense — however fashionable — does little to advance that endeavour.

A left that abandons reason and objectivity is a left that disarms itself in the face of oppression. The stakes are too high for lazy thinking.

The stakes extend beyond academia. A world without shared standards of truth is one where propaganda thrives and solidarity fractures. To defend reason, intellectual rigour, and objectivity is not reactionary; it is a radical act. These are the values that allow us to distinguish critique from conspiracy, justice from jargon, and liberation from self-indulgent cynicism.

När ska vi sluta använda de arbetslösa som inflationssköld?

14 Jan, 2026 at 12:03 | Posted in Economics | 7 Comments

Regeringen genomför nu en historisk omläggning av arbetsmarknadspolitiken. A-kassan trappas ned, bidragen stramas åt och hårda aktivitetskrav införs. Budskapet är tydligt: det ska löna sig bättre att arbeta, och kosta mer att vara arbetslös.

Många på vänsterkanten avfärdar detta som ren elakhet mot de utsatta. Men det är ett misstag att förenkla regeringens strategi till att bara handla om moral. Deras linje är inte bara ideologisk, den är logisk – givet den ekonomiska modell som styrt Sverige i decennier.

Både regeringen och myndigheterna utgår från en modell där det finns en nivå av arbetslöshet som inte får underskridas om vi ska hålla inflationen i schack, den så kallade jämviktsarbetslösheten eller NAIRU (på engelska: Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment). I praktiken innebär det att hundratusentals människor används som en inflationssköld – en arbetslöshetsbuffert. De måste enligt modellen stå utanför arbetsmarknaden för att dämpa löneökningar och hindra priserna från att stiga.

Regeringens analys är krass men konsekvent: NAIRU är hög för att arbetslösa är för “dyra” och trygga. Deras strategi är därför att driva fram en sänkning av lönegolvet. Genom att göra alternativet till arbete – bidrag och a-kassa – så magert och osäkert som möjligt, tvingar man människor att söka jobb till lägre löner och sämre villkor.

Dras denna strategi till sin spets kan den mycket väl minska NAIRU. I teorin kan nämligen en arbetsmarknad alltid “cleara” om priset på arbete blir tillräckligt lågt. Men till vilket pris? Är en framväxt av “working poor” och social misär en framgång, bara för att statistiken snyggas till?

I den grundläggande modell som används av dagens mainstream makroekonomer är arbetsmarknaden alltid i jämvikt — den representativa agenten maximerar sin nyttofunktion genom att anpassa sitt arbetsutbud, penninghållning och konsumtion över tid som svar på förändringar i räntan, förväntad livstidsinkomst eller reallön. Viktigast av allt — om reallönen av någon anledning avviker från sitt ‘jämviktsvärde’, justerar agenten sitt arbetsutbud så att när reallönen är högre än jämviktsvärdet ökar arbetsutbudet, och när reallönen är under jämviktsvärdet minskar arbetsutbudet.

I denna modellvärld är arbetslöshet alltid ett optimalt val som svar på förändrade förhållanden på arbetsmarknaden. Därmed är arbetslöshet helt frivillig. Att vara arbetslös är något man optimalt väljer — en slags förlängd semester.

Även om denna bild av arbetslöshet som en slags självvald optimalitet för de flesta framstår som fullständigt absurd, verkar Tidöpartierna ha fullt ut anammat denna Walt Disney världsbild av varför vi har den tredje högsta arbetslösheten i EU.

Istället för att verkligen göra rejäla arbetsmarknadssatsningar för att få ned den rekordhöga arbetslösheten väljer regeringen att minska på bidrag till redan utsatta familjer. Folk — framför allt de med invandrarbakgrund — sägs frivilligt avstå från att etablera sig på arbetsmarknaden och istället leva på de bidrag man får om man skaffar flera barn. Sänker man bidragen kommer de här flerbarnsföräldrarna att få det sämre och därför helt rationellt välja att göra rätt för sig och etablera sig på arbetsmarkanden.

Ja vad ska man säga om denna verklighetsuppfattning? Man tager sig för pannan!

Ja vad ska man säga om denna verklighetsuppfattning? Man tager sig för pannan!

När det gäller det av Arnell och Hansen kritiserade begreppet NAIRU kan man väl bara tillägga att detta, som så mycket annat i mainstreamekonomernas verktygslåda, är ett rent påhitt!

Många politiker och ekonomer ansluter sig till NAIRU-berättelsen och dess politiska implikation att försök att främja full sysselsättning är dömda att misslyckas, eftersom regeringar och centralbanker inte kan pressa ned arbetslösheten under den kritiska NAIRU-tröskeln utan att orsaka skadlig galopperande inflation.

Även om detta kan låta övertygande är det helt felaktigt!

Ett av huvudproblemen med NAIRU är att det i grunden är en tidlös jämviktsattraktor på lång sikt, till vilken den faktiska arbetslösheten (påstås) måste anpassa sig. Men om denna jämvikt själv förändras — och på sätt som beror av processen att nå jämvikten — ja, då kan vi inte vara säkra på vad den jämvikten kommer att vara utan att kontextualisera arbetslösheten i verklig historisk tid. Och när vi gör det kommer vi att se hur allvarligt fel vi går om vi utelämnar efterfrågan från analysen. Efterfrågepolitik har långsiktiga effekter och påverkar även den strukturella arbetslösheten — och regeringar och centralbanker kan inte bara se åt ett annat håll och legitimera sin passivitet när det gäller arbetslösheten genom att hänvisa till NAIRU.

Förekomsten av långsiktig jämvikt är ett mycket praktiskt modellantagande att använda. Men det gör det inte lättapplicerbart på verkliga ekonomier. Varför? För att det i grunden är ett tidlöst koncept fullständigt oförenligt med verkliga historiska händelser. I den verkliga världen är det termodynamikens andra huvudsats och historisk — inte logisk — tid som råder.

Detta betyder i viktiga avseenden att långsiktig jämvikt är ett oerhört dåligt riktmärke för makroekonomisk politik. I en värld full av genuin osäkerhet, multipla jämvikter, asymmetrisk information och marknadsmisslyckanden är den långsiktiga jämvikten helt enkelt en icke-existerande enhörning.

NAIRU håller inte streck helt enkelt för att det inte existerar — och att basera ekonomisk politik på en så svag teoretisk och empirisk konstruktion är inget mindre än att skriva ut ett recept för självförvållad ekonomisk förödelse.

NAIRU är ett värdelöst koncept, och ju förr vi begraver det, desto bättre.

The ‘bad luck’ theory of unemployment

13 Jan, 2026 at 16:06 | Posted in Economics | 1 Comment As is well-known, New Classical economists have never accepted Keynes’s distinction between voluntary and involuntary unemployment. According to New Classical über-economist Robert Lucas, an unemployed worker can always instantaneously find some job. No matter how miserable the work options are, “one can always choose to accept them,” in Lucas’s view.

As is well-known, New Classical economists have never accepted Keynes’s distinction between voluntary and involuntary unemployment. According to New Classical über-economist Robert Lucas, an unemployed worker can always instantaneously find some job. No matter how miserable the work options are, “one can always choose to accept them,” in Lucas’s view.

This is, of course, only what one would expect of New Classical economists.

But, sadly enough, this extraterrestrial view of unemployment is actually shared by ‘New Keynesians,’ whose microfounded DSGE models cannot even incorporate such a basic fact of reality as involuntary unemployment!

Of course, working with micro-founded representative agent models, this should come as no surprise. If one representative agent is employed, all representative agents are. The kind of unemployment that occurs is voluntary, since it is only adjustments to working hours that these optimising agents make to maximise their utility.

In the basic DSGE models used by most ‘New Keynesians’, the labour market is always cleared — responding to a changing interest rate, expected lifetime incomes, or real wages, the representative agent maximises the utility function by varying her labour supply, money holdings, and consumption over time. Most importantly — if the real wage somehow deviates from its “equilibrium value,” the representative agent adjusts her labour supply, so that when the real wage is higher than its “equilibrium value,” labour supply is increased, and when the real wage is below its “equilibrium value,” labour supply is decreased.

In this model world, unemployment is always an optimal choice in response to changes in labour market conditions. Hence, unemployment is entirely voluntary. To be unemployed is something one optimally chooses to be.

If substantive questions about the real world are being posed, it is the formalistic-mathematical representations utilised to analyse them that must match reality, not the other way around.

To Keynes, this was self-evident. But to New Classical and ‘New Keynesian’ economists, it obviously is not.

Cookbook econometrics

12 Jan, 2026 at 18:51 | Posted in Economics | Leave a comment

Alongside the mounting pile of elaborate theoretical models we see a fast-growing stock of equally intricate statistical tools …

[M]ost modeltesting kits described in professional journals are internally consistent. However, like the economic models they are supposed to implement, the validity of these statistical tools depends itself on the acceptance of certain convenient assumptions pertaining to stochastic properties of the phenomena which the particular models are intended to explain; assumptions that can be seldom verified.

In no other field of empirical inquiry has so massive and sophisticated a statistical machinery been used with such indifferent results.

Mark Ruffalo rightfully slams Trump!

12 Jan, 2026 at 18:21 | Posted in Politics & Society | Leave a comment.

Misinterpretation of p-values and statistical uncertainty

11 Jan, 2026 at 22:39 | Posted in Statistics & Econometrics | Leave a commentIt is well known that even experienced scientists routinely misinterpret p-values in all sorts of ways, including confusion of statistical and practical significance, treating non-rejection as acceptance of the null hypothesis, and interpreting the p-value as some sort of replication probability or as the posterior probability that the null hypothesis is true …

It is shocking that these errors seem so hard-wired into statisticians’ thinking, and this suggests that our profession really needs to look at how it teaches the interpretation of statistical inferences. The problem does not seem just to be technical misunderstandings; rather, statistical analysis is being asked to do something that it simply can’t do, to bring out a signal from any data, no matter how noisy. We suspect that, to make progress in pedagogy, statisticians will have to give up some of the claims we have implicitly been making about the effectiveness of our methods …

It would be nice if the statistics profession was offering a good solution to the significance testing problem and we just needed to convey it more clearly. But, no, … many statisticians misunderstand the core ideas too. It might be a good idea for other reasons to recommend that students take more statistics classes—but this won’t solve the problems if textbooks point in the wrong direction and instructors don’t understand what they are teaching. To put it another way, it’s not that we’re teaching the right thing poorly; unfortunately, we’ve been teaching the wrong thing all too well.

Teaching both statistics and economics, yours truly cannot help but notice that the statement “it is not that we’re teaching the right thing poorly; unfortunately, we have been teaching the wrong thing all too well” obviously applies not only to statistics …

And the solution? Certainly not — as Gelman and Carlin also emphasise — to reform p-values. Instead, we have to accept that we live in a world permeated by genuine uncertainty and that it takes a great deal of variation to make good inductive inferences.

Sounds familiar? It definitely should!

The standard view in statistics — and the axiomatic probability theory underlying it — is to a large extent based on the rather simplistic idea that ‘more is better.’ But as Keynes argues in his seminal A Treatise on Probability (1921), ‘more of the same’ is not what is important when making inductive inferences. It is a question of ‘more but different’ — that is, variation.

Variation, not replication, is at the core of induction. Finding that p(x|y) = p(x|y & w) does not make w ‘irrelevant.’ Knowing that the probability is unchanged when w is present gives p(x|y & w) another evidential weight (‘weight of argument’). Running 10 replicative experiments does not make you as ‘sure’ of your inductions as when running 10,000 varied experiments — even if the probability values are the same.

According to Keynes, we live in a world permeated by unmeasurable uncertainty — not quantifiable stochastic risk — which often forces us to make decisions based on anything but ‘rational expectations.’ Keynes rather thinks that we base our expectations on the confidence or ‘weight’ we place on different events and alternatives. To Keynes, expectations are a question of weighing probabilities by ‘degrees of belief,’ beliefs that often have precious little to do with the kind of stochastic probabilistic calculations made by the rational agents modelled by ‘modern’ social sciences. And often we ‘simply do not know.’

Blog at WordPress.com.

Entries and Comments feeds.