Table of Contents

Quick Summary

- Rolling back a kernel means switching from your current Linux kernel to an older, previously installed version.

- If a new kernel update breaks your system, reboot and press Shift (or Esc on UEFI) to reveal the GRUB menu. Then choose "Advanced options" and select an older kernel.

- To make the change permanent in Debian or Ubuntu, edit

/etc/default/grub(settingGRUB_DEFAULTto the older kernel entry) and runsudo update-grub. On RHEL/Fedora, you can use thegrubbytool (for example,sudo grubby --set-default-index=1) to set an older kernel as default. - You can also use the package manager to remove or downgrade the newer kernel package (keeping at least one older version installed). For example, on Debian/Ubuntu use

sudo apt purge linux-image-<new-version>(replace with the actual version). Always confirm the older kernel is still available. - Warning: Kernel rollbacks are advanced operations. They can leave the system unbootable or create driver/module mismatches. Always have backups and a recovery plan before you proceed.

What "Rolling Back" the Linux Kernel Means

As you know already, the Kernel is the core part of Linux. When we talk about rolling back the kernel, we mean going back to an earlier version of the Linux kernel.

This is often done if the latest kernel causes problems (like crashes or missing drivers). It is not a normal update; it's more like a targeted downgrade of the operating system core.

Many Linux distributions keep older kernels installed by default. When you install a new kernel, the old one usually stays in /boot. This allows you to boot into an older kernel if needed.

For example, when a new kernel update makes your system non-bootable, you can always choose the older kernel to boot. Rolling back simply means taking advantage of that safety net by using the older kernel again.

A rollback can fix issues that appeared after a kernel upgrade (hardware no longer working, system instability, etc.). It gives you time to troubleshoot the problem.

Please note that, Linux Kernel rollback is a temporary workaround, not a permanent fix. It does not resolve the underlying bug or missing feature in the new kernel. It just lets you use a known good version for now.

When You might Need a Kernel Rollback

Kernel rollbacks are usually done in emergencies or troubleshooting scenarios. Common reasons include:

- New kernel breaks hardware or drivers: For example, if your network card or graphics stop working after the update.

- Stability issues: The system might crash, hang, or services may fail under the new kernel.

- Compatibility problems: Some applications or peripherals might not be compatible with the latest kernel.

A Linux Kernel rollback makes sense only if a new kernel causes serious failures. Please consider rolling back when the system becomes unstable after an upgrade, critical services fail, or hardware stops working.

Always test the older kernel first. For instance, try booting it once via the GRUB menu to confirm the issue goes away.

This is not a routine operation for minor glitches. If a small bug appears, it may be better to wait for a fix or try a different kernel line (like a Long-Term Support kernel).

Remember that rolling back also removes recent security fixes and updates, so use it sparingly and only as a stopgap.

Key Takeaway:

Rolling back the Linux kernel can save the day when a bad update breaks your system. It should be done carefully, with backups and verification. Use it to regain a stable state, then address the root cause or wait for a fix. When used wisely, it's a useful recovery step – but it is not a routine maintenance tool.

Boot into an Older Kernel using GRUB

Most distros allow you to choose an older kernel at boot time via the GRUB menu. By default, many systems hide the GRUB menu to speed up booting.

To see the GRUB menu hold the Shift key (on BIOS systems) or press Esc (on UEFI systems) right after powering on. This brings up the GRUB boot menu.

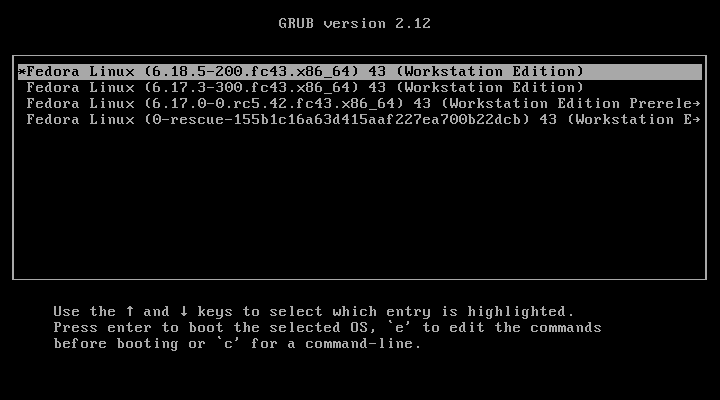

Here's an example screenshot of GRUB boot menu in Fedora:

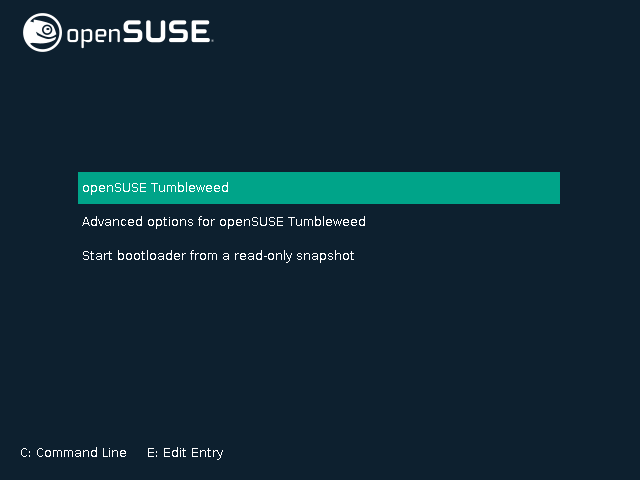

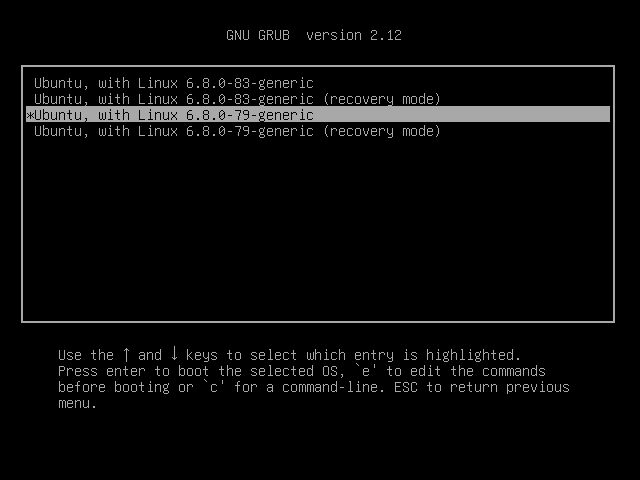

GRUB boot menu in openSUSE:

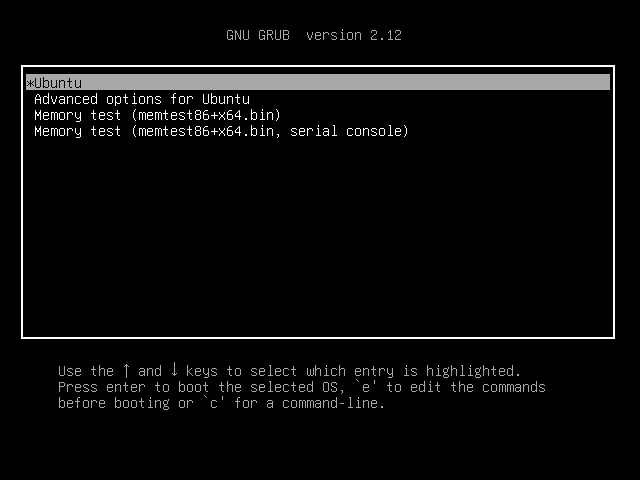

GRUB boot menu in Ubuntu:

Now, let us change to different Kernel.

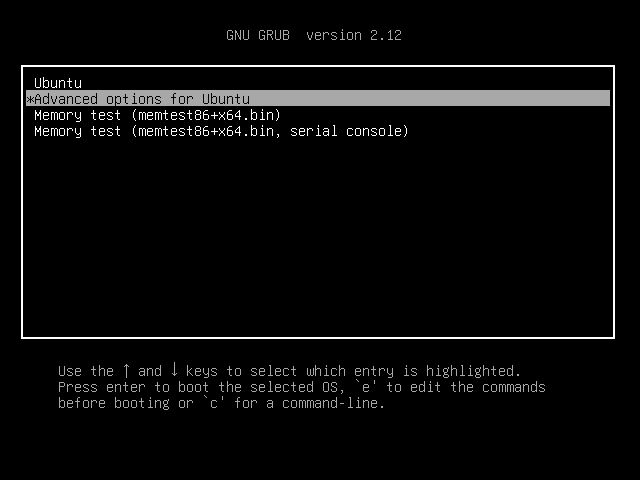

In the GRUB menu (Debian or Ubuntu), look for an entry like "Advanced options for Linux" or similar.

Under that submenu you will see a list of installed kernel versions. Select the previous (older) kernel from the list. The system will boot using that kernel version.

Please note that there is no sub-menu in Fedora. Simply choose the Kernel from Grub menu and hit ENTER to boot into the selected Kernel.

This method only changes the kernel for the current boot. It's useful for testing: if the older kernel boots successfully and your hardware/drivers work, you've identified that the new kernel was the problem.

You can then proceed to make this change permanent (as described in the next section) or try other fixes.

Making the Older Kernel the Default

If the older kernel works well and you want to keep using it, you can make it the default boot option.

Change the Default Kernel by Editing GRUB configuration in Debian, Ubuntu and Derivatives

Open /etc/default/grub in a text editor with sudo:

sudo nano /etc/default/grub

Find the line GRUB_DEFAULT=0. You can change it to the menu entry of the older kernel. For example, you might set GRUB_DEFAULT="1>2" to pick the 3rd kernel in the 2nd submenu. The format "X>Y" means GRUB's X-th menu, then Y-th item.

Confused? Well, allow me to explain with an example in the next section.

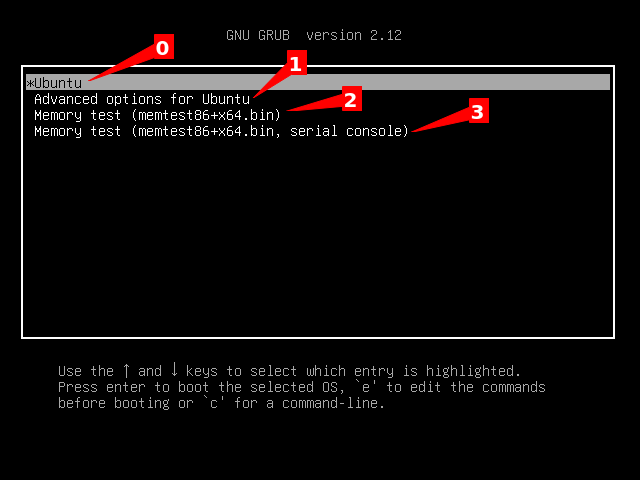

Understanding GRUB Menu Entries in Ubuntu (Important)

On Ubuntu systems, Kernel versions are not shown in the main GRUB menu. They are stored under Advanced options for Ubuntu.

This means GRUB_DEFAULT must use a submenu path, not a simple number.

In general, GRUB numbering starts at 0, not 1.

Here are the menu entries in the main GRUB menu in Ubuntu 24.04:

0 Ubuntu 1 Advanced options for Ubuntu 2 Memory Test (memtest86+64bin) 3 Memory Test (memtest86+64bin, serial console)

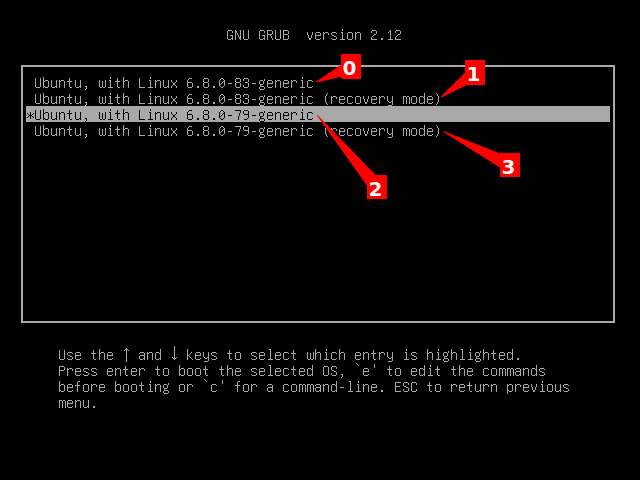

Inside Advanced options for Ubuntu:

0 Ubuntu, with Linux 6.8.0-83-generic 1 Ubuntu, with Linux 6.8.0-83-generic (recovery) 2 Ubuntu, with Linux 6.8.0-79-generic 3 Ubuntu, with Linux 6.8.0-79-generic (recovery)

To boot the older kernel (E.g. 6.8.0-79-generic) by default, you need to edit /etc/default/grub file.

Before making any changes, backup the grub file:

sudo cp /etc/default/grub /etc/default/grub.bak

And then edit it using your favourite text editor:

sudo nano /etc/default/grub

Find the following line:

GRUB_DEFAULT=0

This setting will boot the kernel appears directly on the first main GRUB screen.

To set 6.8.0-79-generic as your default Kernel, change:

GRUB_DEFAULT="1>2"

Important Note: If you use X>Y, it must be in quotes — or GRUB will ignore it.

This means:

- 1 → "Advanced options for Ubuntu"

- 2 → the older kernel inside that submenu

After saving /etc/default/grub, run the following command to regenerate the boot menu.

sudo update-grub

On next reboot, GRUB will load the chosen older kernel by default.

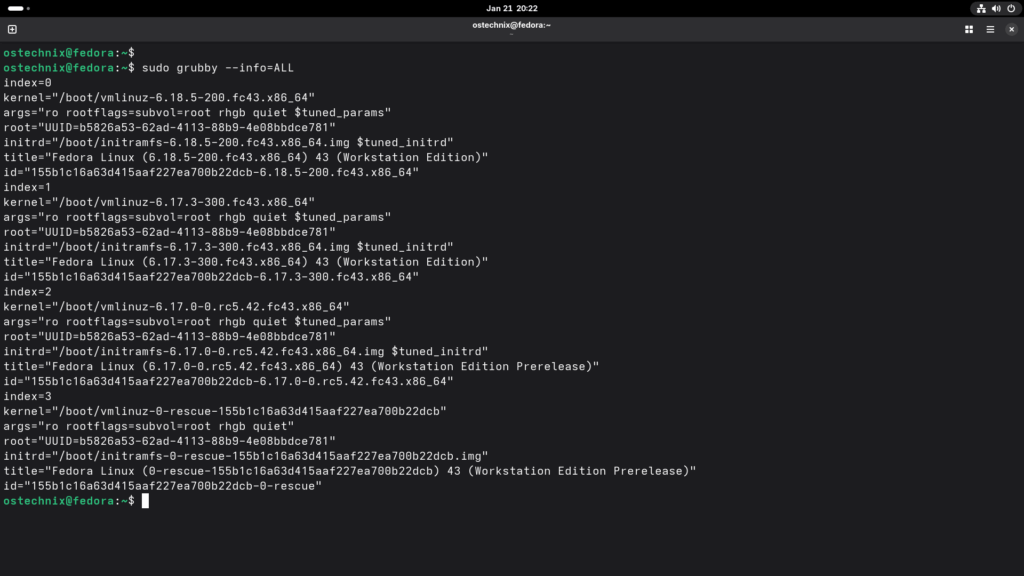

Change the Default Kernel using grubby on RHEL, Fedora

The latest Fedora and RHEL systems use the grubby tool to manage kernels.

First list installed kernels with command:

sudo grubby --info=ALL

This shows each kernel's index number. As I already mentioned earlier, the index numbers always start with 0, not 1.

Then set the default by index. For example:

sudo grubby --set-default-index=1

This will make the kernel with index 1 (the second listed) the default on boot. You can verify with command:

sudo grubby --default-title

Use dnf (or yum) on Fedora/RHEL

If the older kernel isn't installed, you can install it with command:

dnf install kernel-<version>

Once it's installed, you can use grubby as above, or manually edit GRUB config. After that, you may remove the faulty newer kernel with sudo dnf remove kernel-core-<bad-version>, making sure at least one older kernel remains.

Use Package Holds/Pinning

To prevent the newer kernel from coming back with updates, you can hold the kernel package.

For example on Debian/Ubuntu, use:

sudo apt-mark hold linux-image-<version>

For details about package pinning on Ubuntu, check the following guide:

On Fedora, you can use the dnf versionlock command to prevent Kernel from being updated.

Pick the kernel you trust. Example:

6.17.3-300.fc43.x86_64

To lock it, simply run:

sudo dnf versionlock add kernel-6.17.3-300.fc43.x86_64

Verify:

sudo dnf versionlock list

This ensures automatic updates won't replace your chosen kernel until you remove the hold.

Verification:

After making changes, reboot to confirm the system uses the older kernel by default.

Run uname -r to check the active kernel version.

Also test that all critical hardware and services are functioning under the rolled-back kernel.

It's highly recommended to keep at least one working kernel in reserve in case you need to switch back.

Using the Package Manager to Revert to Previous Kernel

If simply choosing the older kernel at boot isn't enough, you can also revert via your package manager:

Debian/Ubuntu

List available kernels with command:

dpkg -l 'linux-image-*'

Remove the problematic one with:

sudo apt purge linux-image-<new-version>

Replace <new-version> with the exact package name.

Do not delete files from /boot manually. If you use apt to remove the kernel packages, it will update the bootloader automatically or prompt you to run:

sudo update-grub

If you did not use the package manager (e.g. installed a custom kernel), you must run sudo update-grub after removal.

Always ensure that at least one older kernel image is left installed, or the system could become unbootable.

Fedora/CentOS/RHEL

To rollback to old Kernel, you can use either dnf or yum.

For example, to downgrade to kernel 6.12 you might run:

sudo dnf install kernel-6.12*

Or to remove a new one:

sudo dnf remove kernel-core-<new-version>

Please note that the running kernel cannot be removed while in use. If you attempt to remove the current kernel (without first booting into another), the system will warn you that it may become unbootable. Always reboot into the older kernel before uninstalling the newer one.

Arch Linux

Arch Linux typically only keeps one kernel installed by default. You can install the longterm (LTS) kernel package (linux-lts) alongside the main kernel.

After installation, update GRUB:

sudo grub-mkconfig -o /boot/grub/grub.cfg

and select the LTS kernel on boot.

For downgrading Arch's kernel, you might need to use the Arch Archive to get old packages or use an AUR package.

SUSE/openSUSE

If you are on a Btrfs setup, you might use Snapper to roll back a snapshot (which includes the kernel). Alternatively, openSUSE often keeps the last two kernels by default, and you can select the older one in the boot menu or set it via zypper.

Each distribution is slightly different, but the principle is the same: ensure the older kernel package is installed, remove or ignore the bad one, and update the bootloader. Afterward, check uname -r and lsblk or lsmod to ensure everything is consistent.

Other Rollback Options

System Snapshots

Tools like Timeshift (or Btrfs/Snapper snapshots) can roll back the entire system state, including the kernel. This is a broader approach. However, it reverts all system files, not just the kernel.

If you're not sure what is causing a problem, rolling back everything may mask the issue. It's often better to isolate the kernel by itself.

If you have problems even after rolling back the kernel with Timeshift, then the kernel wasn't the only issue.

Manual Kernel Install

As a last resort, you can download and compile an older kernel from kernel.org. This is advanced and not recommended for beginners.

If you do, install it carefully (using make install or custom .deb/.rpm) and ensure GRUB is updated. Again, use caution with manual kernels as they may not integrate cleanly with your distro's package system.

In general, the simplest and safest rollback methods use your distribution's tools (GRUB menus and package manager) rather than manual copying of files.

Alternatively, you can use Mainline, a graphical application specifically designed for installing Ubuntu Mainline Kernel builds on Debian-based distributions. For more details, check the following link:

⚠️ Warning: Modifying kernels is risky. Removing or misconfiguring kernels can make your system non-bootable. Do not delete kernel files manually from

/boot. Removing a running kernel image will delete/boot/vmlinuz-…and its modules, which can only be fixed by restoring those files. Always confirm the older kernel boots properly before deleting anything. Backup your data and configs first. Keep a live USB or rescue mode ready in case the system fails to start.

Verify Kernel Versions and Test Everything

After rolling back the kernel, always verify the outcome:

Check the kernel version:

Run uname -r to confirm you are on the expected older kernel.

Test hardware and services:

Make sure that the problem is fixed and that hardware (Wi-Fi, graphics, USB, etc.) and services (networking, storage drivers, etc.) are working correctly with the older kernel.

Review boot order:

Ensure GRUB's default now points to the older kernel. And then re-run the following command to regenerate the boot menu:

sudo update-grub

Or

grub2-mkconfig

To verify on RHEL systems, run:

grubby --default-kernel

Observe logs:

Look at dmesg or /var/log/syslog to see if any errors related to kernel modules appear.

Plan next steps:

If the older kernel is stable, you may hold its version and wait for a fix in the newer release. Make sure to document the change, so you remember which kernel version is known good.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

1. Forgetting to update GRUB:

If you edit /etc/default/grub, don't forget to run: sudo update-grub (Debian/Ubuntu) or sudo grub2-mkconfig -o /boot/grub2/grub.cfg (RHEL/CentOS). Without this, GRUB won't know about your changes.

2. Removing all kernels:

Never remove all kernel images. Always leave at least one working kernel. If you remove the current one, first reboot into a different kernel. The system may warn you if you try to remove the running kernel.

3. Manual file deletion:

Don't manually delete vmlinuz or initramfs files in /boot. Use the package manager to uninstall kernels. A direct file deletion can break the bootloader’s menu and make recovery difficult.

4. Wrong GRUB entry:

When setting GRUB_DEFAULT, make sure you use the correct menu entry. It's easy to miscount indexes. You can list entries with grep menuentry /boot/grub/grub.cfg. Using the "saved" feature (with GRUB_DEFAULT=saved and grub-set-default) is less error-prone than hardcoding indexes.

5. Hardware or module mismatches:

Remember that rolling back might expose other mismatches. If you installed new kernel modules (for example, via DKMS), the old kernel might not have the right module version. Watch for module load errors and reinstall or rebuild modules as needed.

Recommended Read:

When (and When Not) to Rollback Kernel

When to use rollback:

If you've booted the new kernel and encountered crashes, incompatibilities, or missing drivers that prevent normal operation. In those cases, boot into the older kernel to regain stability and continue working or booting.

When not to use rollback:

For minor annoyances or cosmetic bugs. Don't roll back for trivial issues that might be resolved by other means (e.g. reinstalling drivers, waiting for patches, or using kernel parameters).

Conclusion

Rolling back the Linux kernel should be your last-resort. Do it when a new kernel update causes serious system failures or hardware issues. It can restore a working state quickly.

However, it is not a substitute for proper updates and fixes: the underlying issue still needs resolution, and you'll miss out on any new fixes in the updated kernel.

Avoid rolling back on production systems without a plan for how to update safely later.

Always proceed with caution. Rolling back can leave the system unbootable or insecure if done incorrectly. Keep backups handy. Once you're back on a stable kernel, monitor updates.

When a new kernel fix is released (or once you diagnose the problem), you may switch back to a newer kernel in a controlled way.