by Sara Weingartner

Before we dive into creative inspiration, I want to take a moment to check in with you all. How are you, emotionally? I’m in Minneapolis. The weight of the world is overwhelming—with fear, anger and sadness for what is happening to Minnesotans, my neighbors, the businesses, our schools, our whole community.

If even a little bit of this resonates with you, take a moment. And breathe. In times like this, the act of writing and art making can be our place for peace or meditation. What we create can also become a moment of calm, or hope, or joy for anyone who sees it.

(Thanks for letting me be real for a moment. Now onto the inspiration part…)

As an artist, I’ve always loved brainstorming and creating characters and imaginary worlds. So, when I discovered Storystorm back in 2013 (when it was PiBoIdMo) even though I hadn’t declared myself a writer yet, my journey as a PB writer began.

For me, PB ideas often begin with a character that I’ve drawn or one that is stuck in my head, pleading to come out on paper. As I play around with animal vs. human, body shape, clothes and accessories, it slowly reveals its personality.

It’s wonderful to be able to draw out my first impressions of a character. But I often don’t have a clear picture or direction of whom this character is, its hobbies, friends or setting.

That’s when “branching” ideas can be super helpful.

Here’s how it works:

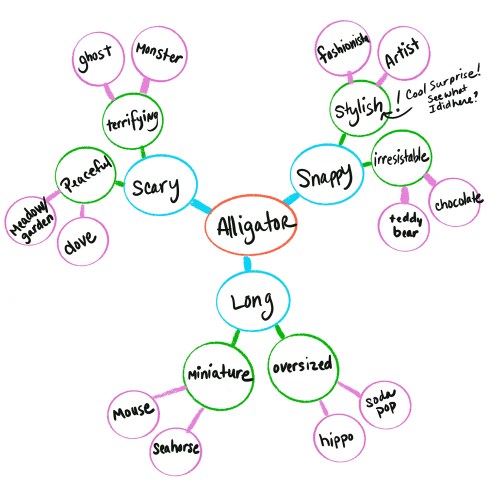

- (RED) Draw a circle in the middle of your paper and choose a character you’re interested in (animal, person, object, place),

- (BLUE) Branch out and draw three (or more) circles. Think up characteristics or qualities (realistic or imaginary) about this character.

- (GREEN) From those three words, branch out again, but this time, with two circles each. Fill with 1) the opposite, and 2) the extreme versions of each quality/characteristic.

- (PURPLE) Last branching, add two more circles each, and fill with nouns that also possess this quality or characteristic.

I hope I didn’t lose you. (Download Sara’s Branching Template here.)

Here’s my quick branching example of an alligator for clarity:

Now comes the fun, brainstorming part! Combine these words to create new character(s), a possible setting, even a friend. So, instead of my initial idea of a (boring) long, snappy, scary alligator, I’ve just imagined a mini alligator fashionista who goes everywhere with her teddy bear, who might be best friends with a confident mouse artist, and maybe this story takes place in a peaceful meadow.

You’re welcome! Now you give it a try!

But first, a few tips:

- TIP 1: Set a timer. Maybe 5-10 mins. Because with a tick-tocking clock, we tend to think quicker and avoid self-editing.

- TIP 2: Use a thesaurus! Choosing words from a list, speeds up your process, and offers multiple meanings of a word. (Note my “stylish” word choice above.)

- TIP 3: I’ve attached a blank branching template PDF if you think it’s more fun to fill in circles.

After you come up with a potential character with weight, dive deeper:

- WHO are they?

- WHAT do they really want?

- HOW are they going to get it?

- WHAT is at stake if they don’t?

- WHERE does this story take place?

- and ask WHAT IF? (if you get stuck along the way).

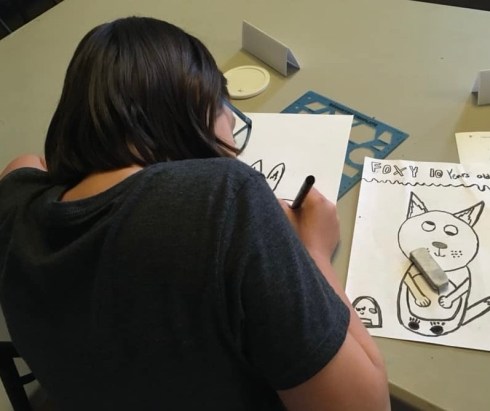

As an added BONUS, challenge yourself to draw your character! And I already don’t believe you if you say, “But I can’t even draw a stick figure.” YES YOU CAN! Just try.

But most of all, enjoy the creative flow because this is what we are made to do! Thank you, Tara, for this opportunity to share, and for all of you for choosing to be on this journey, too.

Sara Weingartner has illustrated nine books (PBs and an early chapter) and is currently submitting her author-illustrator dummies to agents. She works in mixed media (traditional and digital) and is a graphic designer who has designed tons of PBs for a local publisher. Sara is happiest when she’s creating things, being active, and filling her world with color. She also loves throwing pottery (on a wheel!), pickleball, baking and running. She dreams of an inclusive world, believes in magic, and wishes animals could talk. Living in Minnesota, Sara and her husband have two kids (an adult art teacher and teen) and a very spoiled pooch.

Sara Weingartner has illustrated nine books (PBs and an early chapter) and is currently submitting her author-illustrator dummies to agents. She works in mixed media (traditional and digital) and is a graphic designer who has designed tons of PBs for a local publisher. Sara is happiest when she’s creating things, being active, and filling her world with color. She also loves throwing pottery (on a wheel!), pickleball, baking and running. She dreams of an inclusive world, believes in magic, and wishes animals could talk. Living in Minnesota, Sara and her husband have two kids (an adult art teacher and teen) and a very spoiled pooch.

Visit her at SaraWeingartner.com or on Instagram @sarajweingartner and Bluesky @saraweingartner.

Ann Diament Koffsky is the award-winning author and illustrator of more than 50 books for children.

Ann Diament Koffsky is the award-winning author and illustrator of more than 50 books for children.

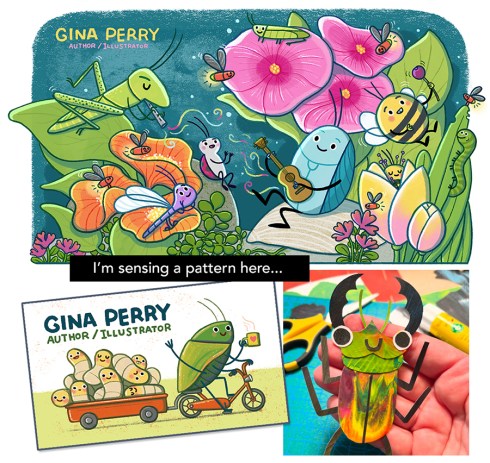

Gina Perry is an author and illustrator from New England. Her latest picture book, THE KING OF BOOKS, is out now from Feiwel & Friends. She is also the creator of the monthly illustrator event #KidLitArtPostcard. You can find Gina on Instagram

Gina Perry is an author and illustrator from New England. Her latest picture book, THE KING OF BOOKS, is out now from Feiwel & Friends. She is also the creator of the monthly illustrator event #KidLitArtPostcard. You can find Gina on Instagram

Marcie Colleen is the author of numerous acclaimed books for young readers. Her writing spans picture books, chapter books, and comics. No matter the format, her stories reflect a deep love of community, creativity, and joyful connection. For more information about Marcie’s projects, visit ThisisMarcieColleen.com. You can also find her on Instagram

Marcie Colleen is the author of numerous acclaimed books for young readers. Her writing spans picture books, chapter books, and comics. No matter the format, her stories reflect a deep love of community, creativity, and joyful connection. For more information about Marcie’s projects, visit ThisisMarcieColleen.com. You can also find her on Instagram  Michael Leali is the award-winning author of The Civil War of Amos Abernathy, which won SCBWI’s Golden Kite Award. His work has also been twice nominated for Lambda Literary Awards among many other honors. His other middle grade novels include Matteo and The Truth About Triangles. He is a veteran high school English teacher, a seasoned writing coach, and he now teaches creative writing at the University of San Francisco. He holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Follow Michael on Instagram

Michael Leali is the award-winning author of The Civil War of Amos Abernathy, which won SCBWI’s Golden Kite Award. His work has also been twice nominated for Lambda Literary Awards among many other honors. His other middle grade novels include Matteo and The Truth About Triangles. He is a veteran high school English teacher, a seasoned writing coach, and he now teaches creative writing at the University of San Francisco. He holds an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Follow Michael on Instagram  The first time I remember seeing a piece of work character was in that most iconic of children’s books, Maurice Sendak’s WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE. Many people understandably comment on the Caldecott-winning art and the indelible images of the wild things as reasons for why the book has endured for each new generation of readers. But I think what children most respond to is the subtle message that Max, who acts badly and never actually apologizes, is not seen as a ‘bad child’ but as a child who is still learning about lashing out and seemingly unfair consequences and above all, is a child who is still deserving of love (and what is love but a parent who leaves their child a hot supper after a tantrum).

The first time I remember seeing a piece of work character was in that most iconic of children’s books, Maurice Sendak’s WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE. Many people understandably comment on the Caldecott-winning art and the indelible images of the wild things as reasons for why the book has endured for each new generation of readers. But I think what children most respond to is the subtle message that Max, who acts badly and never actually apologizes, is not seen as a ‘bad child’ but as a child who is still learning about lashing out and seemingly unfair consequences and above all, is a child who is still deserving of love (and what is love but a parent who leaves their child a hot supper after a tantrum). In my new early reader, OLIVE & OSCAR: THE FAVORITE HAT, illustrated by Marc Rosenthal, I knew Olive would be the “piece of work” character. Her first act is actually kind as she gifts her friend Oscar the aforementioned hat. But as the day goes on and the friends find themselves in need of objects (something to dig sand with, something to hold groceries when a bag breaks, etc.), Olive volunteers Oscar’s new hat without hesitation and without much thought as to whether it’s an appropriate use of Oscar’s hat or if Oscar himself wants to use his new hat for such purposes. Some people (adults) would recognize this behavior as less than ideal as Olive is being rather presumptuous. But at a kid level through a kid lens, it makes sense. If you don’t have a shovel for sand, why not use a hat? It’s there. Why should a kid be expected to think first of the consequences of a sand filled hat? Just because Olive is making a bad decision doesn’t mean she’s a bad kid. She’s just a kid. A work-in-progress kid. Who also happens to be a “piece of work.”

In my new early reader, OLIVE & OSCAR: THE FAVORITE HAT, illustrated by Marc Rosenthal, I knew Olive would be the “piece of work” character. Her first act is actually kind as she gifts her friend Oscar the aforementioned hat. But as the day goes on and the friends find themselves in need of objects (something to dig sand with, something to hold groceries when a bag breaks, etc.), Olive volunteers Oscar’s new hat without hesitation and without much thought as to whether it’s an appropriate use of Oscar’s hat or if Oscar himself wants to use his new hat for such purposes. Some people (adults) would recognize this behavior as less than ideal as Olive is being rather presumptuous. But at a kid level through a kid lens, it makes sense. If you don’t have a shovel for sand, why not use a hat? It’s there. Why should a kid be expected to think first of the consequences of a sand filled hat? Just because Olive is making a bad decision doesn’t mean she’s a bad kid. She’s just a kid. A work-in-progress kid. Who also happens to be a “piece of work.”

I would add my picture book MABEL WANTS A FRIEND, also illustrated by Marc Rosenthal. It was suggested that I remove the scene where Mabel stole a child’s toy in case it made Mabel too unlikeable. I decided to keep the scene because I felt the reader needed to see who Mabel truly was, warts and all, before a friendship helped changed her desires and priorities. Mabel did a particularly bad thing, and while she deserved her friend Chester’s condemnation, she also deserved a chance to learn and grow from her mistake.

I would add my picture book MABEL WANTS A FRIEND, also illustrated by Marc Rosenthal. It was suggested that I remove the scene where Mabel stole a child’s toy in case it made Mabel too unlikeable. I decided to keep the scene because I felt the reader needed to see who Mabel truly was, warts and all, before a friendship helped changed her desires and priorities. Mabel did a particularly bad thing, and while she deserved her friend Chester’s condemnation, she also deserved a chance to learn and grow from her mistake. Ariel Bernstein is an author of picture books including WE LOVE FISHING! (starred review Publisher’s Weekly), YOU GO FIRST (starred review Kirkus Reviews), and MABEL WANTS A FRIEND (starred reviews Kirkus Reviews and Publisher’s Weekly), all illustrated by Marc Rosenthal. She also wrote the WARREN & DRAGON chapter book series, illustrated by Mike Malbrough. Honors include a Publisher’s Weekly Best Book of 2024, Charlotte Zolotow Highly Commended Title, Junior Library Guild Gold Selections, CCBC Choices, and Bank Street College Best Book of the Year. Ariel lives in New Jersey with her family and you can find her online at

Ariel Bernstein is an author of picture books including WE LOVE FISHING! (starred review Publisher’s Weekly), YOU GO FIRST (starred review Kirkus Reviews), and MABEL WANTS A FRIEND (starred reviews Kirkus Reviews and Publisher’s Weekly), all illustrated by Marc Rosenthal. She also wrote the WARREN & DRAGON chapter book series, illustrated by Mike Malbrough. Honors include a Publisher’s Weekly Best Book of 2024, Charlotte Zolotow Highly Commended Title, Junior Library Guild Gold Selections, CCBC Choices, and Bank Street College Best Book of the Year. Ariel lives in New Jersey with her family and you can find her online at

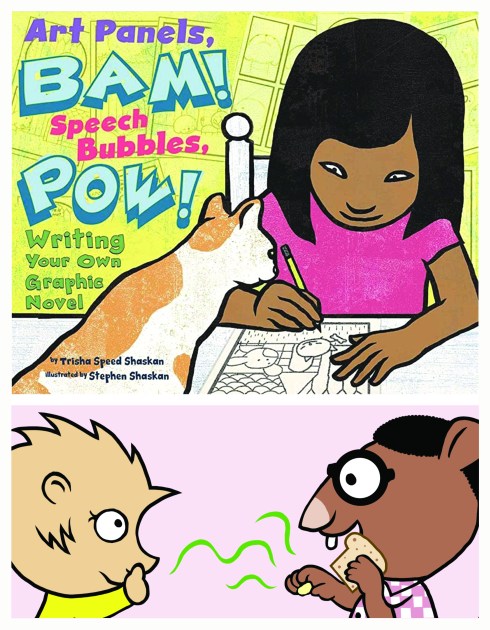

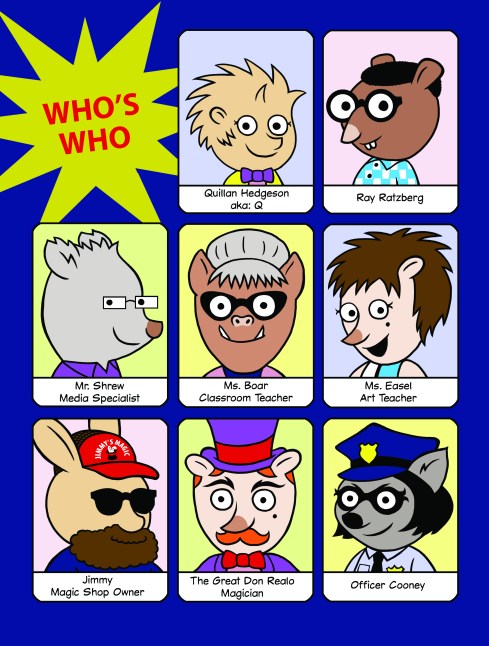

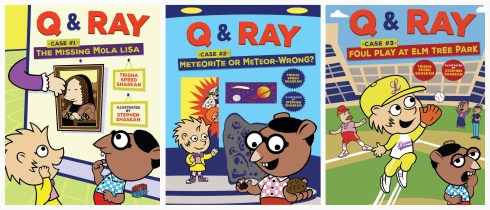

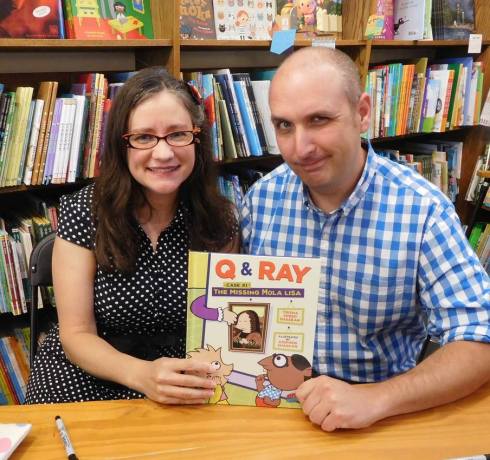

Trisha Speed Shaskan has written fifty books for children, including her latest picture book The Itty-Bitty Witch illustrated by Xindi Yan. Trisha and her husband/author/illustrator Stephen Shaskan have created the picture book Punk Skunks and Q & Ray graphic novel series. They love to visit elementary schools and libraries where they share their passion for creating books for children. Trisha has taught creative writing to students at every level from kindergarten to graduate-school. She has an MFA in creative writing from Minnesota State University. Trisha and Stephen live in Minneapolis, MN with their beloved dogs, Beatrix and Murray. Visit Trisha at

Trisha Speed Shaskan has written fifty books for children, including her latest picture book The Itty-Bitty Witch illustrated by Xindi Yan. Trisha and her husband/author/illustrator Stephen Shaskan have created the picture book Punk Skunks and Q & Ray graphic novel series. They love to visit elementary schools and libraries where they share their passion for creating books for children. Trisha has taught creative writing to students at every level from kindergarten to graduate-school. She has an MFA in creative writing from Minnesota State University. Trisha and Stephen live in Minneapolis, MN with their beloved dogs, Beatrix and Murray. Visit Trisha at

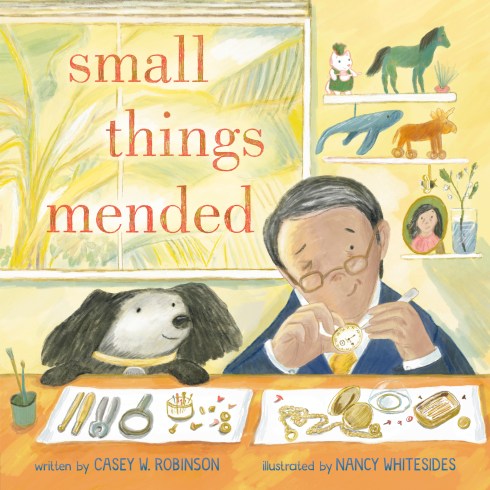

Casey W. Robinson’s latest picture book, SMALL THINGS MENDED, illustrated by Nancy Whitesides, was a New England Book Award winner, a Christopher Award winner, a Crystal Kite Award winner, and received a 2025 Massachusetts Book Award Honor. Casey’s debut picture book, IVER AND ELLSWORTH, illustrated by Melissa Larson, was a finalist for the Crystal Kite Award and Pennsylvania Young Reader’s Choice Award. Her next book, THE SHARING HOUSE, illustrated by Mary Lundquist (Rocky Pond Books/Penguin), will be out in May 2027.

Casey W. Robinson’s latest picture book, SMALL THINGS MENDED, illustrated by Nancy Whitesides, was a New England Book Award winner, a Christopher Award winner, a Crystal Kite Award winner, and received a 2025 Massachusetts Book Award Honor. Casey’s debut picture book, IVER AND ELLSWORTH, illustrated by Melissa Larson, was a finalist for the Crystal Kite Award and Pennsylvania Young Reader’s Choice Award. Her next book, THE SHARING HOUSE, illustrated by Mary Lundquist (Rocky Pond Books/Penguin), will be out in May 2027.

Courtney Pippin-Mathur is the author and or illustrator of several picture books including Dinosaur Days (author), Maya was Grumpy, and Dragons Rule, Princesses Drool. She makes lots of other types of art including paper machè, clay and acrylic painting. She teaches online (and occasionally in person) at The Highlights Foundation and through personal mentorships.

Courtney Pippin-Mathur is the author and or illustrator of several picture books including Dinosaur Days (author), Maya was Grumpy, and Dragons Rule, Princesses Drool. She makes lots of other types of art including paper machè, clay and acrylic painting. She teaches online (and occasionally in person) at The Highlights Foundation and through personal mentorships.