Out of Africa

For his latest album, Lionel Loueke takes on the subject of 21st-century migration and reckons with his own winding artistic path

By Ted Panken

“You don’t just choose to get on a boat because you want to live in Europe. It’s because you have nothing else to lose. Many people in the West don’t get that point.”

“If you don’t take risks, you don’t get anything back. If you don’t believe it, you can’t expect anyone else to believe it.”

In early October, just after concluding two concerts in Kuwait City with Herbie Hancock and two weeks before embarking on a month of European one-nighters with Dave Holland’s Aziza quartet, Lionel Loueke was on the phone from Switzerland. The subject was his 2018 release, The Journey (Aparté), which contains 15 of the guitarist/singer’s compositions. Some are instrumental, but on most Loueke applies his lilting tenor to lyrics in Fon, French, Mina, and Yoruba, all languages spoken in his homeland, Benin, on the Atlantic coast of equatorial Africa.

“I was thinking about this project for a long time,” said Loueke, who’d spent the day teaching at the Jazz Campus of Musik Akademie Basel. “I wanted to do an acoustic, melody-oriented project that mixed all my influences from the beginning to where I am today, combining classical musicians and instruments with traditional instruments from Africa and jazz musicians in the most organic possible way.”

The album’s title is as multi-layered as its contents. On one level, it’s about why so many Africans have decided to leave their homes and take the perilous journey to Europe—and the stark conditions they face upon arrival. Loueke frames this story of modern migration within a succession of lovely melodies, orchestrated by Robert Sadin, a favored collaborator of Herbie Hancock (Gershwin’s World) and Wayne Shorter (Alegría), and interpreted by a cohort of virtuosos from the U.S., Europe, Brazil, the Caribbean, and West Africa.

On another level, The Journey also traces Loueke’s path as an artist, which began in Cotonou, Benin’s capital, where he spent much of his teens as a dancer and percussionist, as referenced in the opening track, “Bouriyan.” (The song is named for an Afro-Brazilian carnival rhythm in Ouidah, the hometown of his mother, a schoolteacher and the descendant of emancipated slaves who settled there after leaving Brazil at the turn of the 19th century.) At 17, already familiar with traditional music through his grandfather, a village singer, Loueke began playing his older brother’s guitar, using bicycle cable for strings.

“I was thinking about how to get the sound of the kora or kalimba or djembe, which are not chromatic, on the guitar, but I also got involved in Occidental music playing rock and blues,” Loueke recalled. “At first, I thought everything was just part of the song, because in Africa you sing, then you play, and then you have the verse. When I discovered they were improvising, I became curious. The first time I heard B.B. King, the way he bent the notes reminded me of a three-string instrument in the north of Benin. I could hear where it came from.”

In 1990, Loueke—whose parents were advocating a career as a mathematician or doctor—left Cotonou to study harmony and ethnomusicology at the National Institute of Arts in Ivory Coast, where he first connected to Bach and Stravinsky. In 1994, he moved to Paris for four years of jazz studies; he then matriculated to Berklee on a scholarship, remaining in Boston for another three years. In 2001, a panel including Hancock, Shorter, Terence Blanchard, and Charlie Haden—each a future Loueke employer—admitted the guitarist to the Thelonious Monk Institute in Los Angeles. And in 2003, after more than a decade of formal education, Loueke finally felt prepared to enter the fray as a professional.

Fifteen years on, Loueke, now 45, is a singular figure in jazz and world music circles. Peers and elders deeply respect his individualism; his rhythmic capabilities and exhaustive harmonic knowledge; his ability to sing in one meter and play in another; the way he transforms the guitar into a virtual Afro-Western orchestra through techniques that evoke instruments like the kalimba (by muting his strings with crepe paper) and the talking drum (with help from his DigiTech Whammy pedal). He’s written several popular compositions, most famously “Benny’s Tune,” which Blanchard debuted in 2003. And his improvisations evoke a global array of associations: King Sunny Adé and Tabu Ley Rochereau, George Benson and Wes Montgomery, Derek Bailey and Bill Frisell.

You can get a sense of Loueke’s imagination at its most rampant on Close Your Eyes (Newville), last year’s freewheeling run through eight standards with bassist Reuben Rogers and drummer Eric Harland. It’s an apropos successor to his final two albums for Blue Note, which signed him in 2008: Heritage (2012), an Afrofolkloric hardcore/jazz hybrid featuring keyboardist/co-producer Robert Glasper, bassist Derrick Hodge, and drummer Mark Guiliana; and Gaia (2015), a rock-oriented recital with longstanding trio partners Massimo Biolcati on bass and Ferenc Nemeth on a uniquely configured drumkit made up of West African percussion instruments.

Even before those Blue Note dates, Loueke and Robert Sadin had been discussing a song-oriented project. They didn’t pull the trigger until 2015, when Loueke, in New York for a Carnegie Hall concert with Benin-born singer and frequent collaborator Angélique Kidjo, invited Sadin to hear some demos. The first song was “Bawo,” with a lyric in Yoruba that translates: “How have we come to this? / Modern-day slavery / And climate disruption push / Humanity to the roads of exile.” As recorded on The Journey, Loueke accompanies himself with keening blues lines, propelled by Beninese percussionist Christi Joza Orisha’s talking drums, Pino Palladino’s dancing bassline, and Sadin’s painterly keyboards.

“Robert loved ‘Bawo’ and asked me to send more, so I kept writing and composing,” Loueke said. “We had enough music for a double album, but we chose tunes that best fit the project. Then he came up with the greatest idea—I’d play by myself in the studio for three days. I’d never done anything like that. I had thoughts, but not a clear conception of what I wanted to do. He just let me record, and I came up with ideas that we developed.”

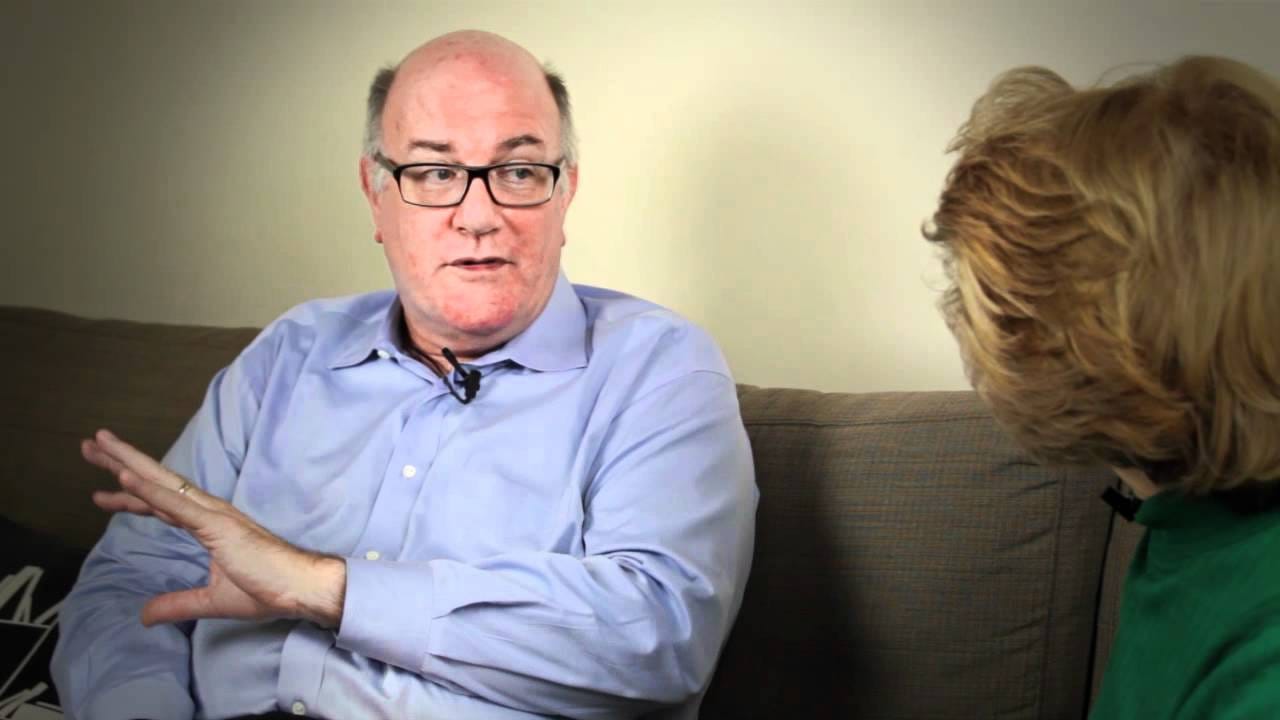

“The key was starting every single song with Lionel playing alone,” said Sadin, who previously produced Loueke’s 2008 album Virgin Forest. “Lionel is so sensitive to other musicians, the nuance in his timing is so great, that he will intuitively adjust himself to and harmonize with the sensibilities and timing of whoever he plays with. It’s like breathing for him. He can’t not do it. I wanted this to be pure, unadorned, with no thought except himself, and we would work everything else around it, including some overdubs from him.”

Loueke had the option to record a fifth album for Blue Note, but Sadin steered him to Aparté, a purist classical label whose roster includes clarinetist Patrick Messina, who’d first performed with Loueke in a Sadin-led septet at the Savannah Music Festival in 2011. That septet also featured percussionist Cyro Baptista, violinist Mark Feldman, and cellist Vincent Ségal, who all contribute to The Journey. According to Sadin, “Aparté wanted to start doing non-classical music that harmonized with their catalog, and they asked me for several names. I told them to start with Lionel. So did Patrick. I sent the owner a demo of ‘Vi Gnin,’ and he said, ‘Fine, that’s our guy—fantastic.’”

Asked why he advocated for Loueke, Sadin gathered his thoughts. “It was a subterranean, global response,” he said. “Leaving aside the giants of the older generation, Lionel is perhaps the single most compelling musician I know. He plays jazz—jazz is a large part of his life—but he’s not a jazz artist; he’s himself.”

Midway through the 2010s, in response to television news images from Africa, Europe, and the waters between—images of shattered vessels, drowned corpses, and squalid refugee camps—Loueke began writing songs like “Bawo” and “Vi Gnin” (“My child, do not cry / War has taken your mother away / Like the wind carries off the roses / Do not worry, she is watching over you”). “I wanted to present a strong musical statement,” he said, “something quieter and gentler than Gaia but delivering the same intense message about how we as humans are taking care of the planet. The idea is a wake-up call to anybody who listens.”

For Loueke, whose move to Europe 25 years ago transpired under very different circumstances, the subject of migration is personal. “I was lucky I didn’t have to take a ship to get to the West,” he said. “It takes courage to jump in a ship, knowing you might die in the ocean. To take such an action means you have no more hope where you’re living. Many people in the West don’t get that point. You don’t just choose to get on a boat because you want to live in Europe. It’s because there’s a war, or there is no more food, or there is modern slavery where you’re living—and you have to get out. You have nothing else to lose. You’d rather die in the ocean than be killed by somebody.”

In the face of such desperation, choosing optimism is difficult, but “Vi Gnin,” “Bawo,” “The Healing,” and—reimagined from Heritage—“Hope (Espoir)” are optimistic nonetheless. “If there’s no more hope, there’s no more life,” Loueke said. “So you keep going because you have a hope, and that’s how you can see a better living situation in the future.”

The guitarist was “in a classical state of mind” when conceiving The Journey’s rubato version of “Hope,” on which Messina’s clarinet and Ségal’s cello interact with his haunting vocal. Similarly, on “Vi Gnin” (where Baptista and Orisha gently complement his acoustic guitar) and “Reflections on Vi Gnin” (a pensive solo instrumental distinguished by spacious volume-pedal swells), he uses “just open triads that you hear a lot in classical music; I’m not playing jazz chords.” He also ascribes classical roots to “Gbêdetemin,” played with Baptista and Orisha, and the kinetic “Molika,” with John Ellis on soprano sax and Baptista on berimbau.

“For me, it’s a great idea to embrace classical music with what I do,” Loueke said. “It opens up my music, and gives classical listeners a different approach. I don’t want to be in a box. I never wanted to play the same thing twice or stay in the same zone.”

Massimo Biolcati and Ferenc Nemeth met Loueke soon after his arrival at Berklee. “Lionel already had something nobody had heard before,” Biolcati recalled. “He was mixing his traditional African guitar style with jazz, and his sense of rhythm was so far beyond anybody in his age group that people were always blown away. He could hear all the West African polyrhythms simultaneously—one day, he’d come in with a tune and count it off in three, the next day he’d do it in four or six.”

“I heard a lot of George Benson influence,” Nemeth said. “He’d learned all of Benson’s solos by heart, because nobody told him it was a solo. In Africa, it’s part of the culture to learn everything in the song. Of course, he already had the African thing, and I played him a lot of music from Hungary and Eastern Europe, things in seven, nine and 11, and classical music by Bartók and Kodály. One time in Hungary he played a concert with Herbie before thousands of people, and in the middle of a solo he played a folk song that my mom taught him before the concert. He’s like a sponge; he hears something, and he can pick it up and incorporate it into his playing.”

The three entered the Monk Institute together, and practiced incessantly. “That’s when he bloomed and created the whole entity of Lionel Loueke,” Nemeth said.

Initially at Berklee, Loueke remarked, “I was trying to learn the jazz tradition, and understand it—to sound like them. Then I started listening to myself, and it was my first hint that I had a different way of playing. We’re all influenced by somebody else, but at some point you have to be yourself.”

While in Los Angeles, Loueke accelerated the process by eschewing guitar picks for a four-finger approach. “I took classical guitar lessons for a year with a great teacher, just to get the right hand technique and sound, though I was playing a jazz guitar,” he said. “Then I bought a classical guitar and focused on that for a year. It was like relearning the instrument. With the pick I had technique, but now I had none. I did it because I saw what I would gain by playing with fingers and nails: being able to play rhythms and counterpoint, and not always playing one or two notes at a time.

“Of course, playing with Herbie for so many years helped me to visualize the instrument differently. He explores new territory every moment. This is the only person I know who plays soundcheck exactly like he’s at the gig, sometimes for several hours. I’ve learned not to be afraid to try new things.

“I’m a risk-taking person,” Loueke added. “A mistake is just for the moment—make it the best mistake it can be, and that’s it. Sometimes a mistake speaks to me strongly, so the first thing I do after the gig is pick up my guitar and revisit it, develop it, make it something I might use. If you don’t take risks, you don’t get anything back. If you don’t believe it, you can’t expect anyone else to believe it.”

Nemeth cosigned Loueke’s self-assessment. “Any time I play something different, he looks at me like, ‘Wow, that’s a new thing I didn’t hear—let’s go for it.’ He’s fearless. That’s what took him out of Benin. That’s what took him on this journey.”

****************

Lionel Loueke (Orvieto, Dec. 31, 2008):

TP: Three years ago, you said that if you could only take six months off…

LIONEL: [LAUGHS]

TP: …you could work on this thing you were hearing, and the next stage. I have a feeling that hasn’t happened.

LIONEL: It hasn’t happened, and I’m still looking for it. Now I’m not looking for six months. Now I’m looking for like a month to stop with.

TP: It seems to have been endless work, a lot of it with Herbie Hancock and developing this trio… Let me ask this. Is the trio you’re working with this week Gilfema, or is Gilfema a different entity than the Lionel Loueke Trio. Talk about how the two are different and similar.

LIONEL: We use Gilfema when we play music from everyone. We have a CD out under Gilfema. When we play the Lionel Loueke Trio, it’s only my music, or I just call it… Maybe I play their tunes, but I’m the one calling the tunes, pretty much. That’s the main difference. But otherwise, it’s the same guys.

TP: I know Gilfema has a new record. But has it been playing?

LIONEL: No, not really. We only did one gig in Paris at the end of my tour with Herbie, and then we have one gig in Boston. So we don’t play that much.

TP: Next year, you’re going to be doing more of your own projects, you were telling me.

LIONEL: Yes. Next year, I think Herbie is not keeping me busy, so I have more free time to do my own thing. So basically, from March to May, we’ll be touring—all of March in Europe, the Lionel Loueke Trio.

TP: Let’s talk about the new Blue Note record. Did it take you a long time to put together? It can’t pinpoint this assertion, but it seems more layered than your previous recording. Of course, having Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter on it doesn’t hurt, but it’s not just them.

LIONEL: I always like to take different directions. It all depends on the moment, what I’m working on or how I feel connected to the music. Karibu definitely is different than Virgin Forest. Virgin Forest was a more produced record. We did some overdubs…I recorded some tracks with musicians in Africa, and even overdubbed some of the stuff. But Karibu is all played in a live context. So the idea for me was, the way I play on stage is pretty much the way I wanted my CD to sound. Just the organic part of it. It’s not perfect. It’s just what it is.

TP: Did you write new compositions for it? There are two standards, of course.

LIONEL: Yes, because the Blue Note people asked me to do it. The title, “Karibu,” was new. “Xala” was new. I don’t remember what else was new… But also, I wanted to play standards, because I like standards. I did “Skylark” and “Naima” with Wayne.

TP: When did you go into the studio to record it?

LIONEL: Karibu I recorded in September. I remember that because my son was born the same week, the first week of September 2007, and it came out at the end of March.

TP: A lot of your work over the prior two years had been in the context of Herbie Hancock’s various bands. You met him in 2001, but you started playing with him in 2004?

LIONEL: Yes.

TP: And you’ve worked with him in what, five different contexts?

LIONEL: Oh, yes, always different. From the summer, we did a tour in the fall which was a completely different band. He always likes to change. And he’s Herbie Hancock! He can do whatever he wants or with whom he wants.

TP: Can you speak to how playing with him has affected your attitude, whether towards presentation, towards musical content. During the summer, I heard you doing your solo feature on “Seventeen” before 10,000 people, and you were playing before these large audiences constantly. I don’t think Terence Blanchard was playing in those kind of venues.

LIONEL: No.

TP: Talk about doing what you do in these less intimate contexts.

LIONEL: Basically, I’m still learning with Herbie, because obviously he knows how to manage those big rooms. For me it’s a big challenge. Every gig he always gives me space to play a solo piece. So to play a solo in front of 20,000 or 2,000 or 3,000 is a big difference, and especially when the audience is far back. I like to feel the vibe from the audience. I learned with Herbie that once you’re out there, you just have to focus and do the best you can, whether there’s two people or 15,000. Musically, I’m learning so much, and that’s the reason I don’t want to stop playing with Herbie, because not only is he giving me so much space, but also the way he carries the whole band and the way he plays differently night to night to me is a real lesson. Besides that, just who he is as a human being and what he’s been doing, all those things affect my playing and my writing as well.

TP: Give me an example.

LIONEL: My writing lately has been very different. Especially on the last tour, we played music by Wayne Shorter, and Herbie also did a new arrangement of “Speak Like A Child,” on which he did an introduction, and playing that every night opened my ears to different… For all of us. We all did writing on the road. Everybody, Terence, Kendrick, everybody was doing writing. It’s so inspiring to see how Herbie developed that introduction every single night. Basically, what I’m trying to do now is, what you compose is pretty much a delay of what you play on live. I’m really trying to get that same kind of vibe when I compose, and not think too much, but at the same time get that freshness.

TP: When you were a young guy, assimilating influences, were you listening to Herbie Hancock’s music, or did that not come until later?

LIONEL: The only thing… I heard something when I started music, but I had no idea it was Herbie Hancock. I was doing the break dance thing. But I didn’t even know it was him. So I was definitely not familiar with his music. I was playing “Cantaloupe Island” or “Watermelon Man,” but I had no clue who wrote them.

TP: Were you playing those songs with African bands.

LIONEL: Exactly. My older brother was playing. They had a band, and they were playing those songs. So when I started learning, they taught me those songs, so I was playing without knowing who wrote them.

TP: When did you start to get familiar with his…

LIONEL: When I moved to Paris, when I went to the American school, then I started to get familiar with him, Wayne, Miles, Coltrane, all those people.

TP: I didn’t see the fall tour, only heard it, but I heard the summer tour, which was almost like an arena show. You have a lot of different roles apart from solo feature. Can you speak about your interplay?

LIONEL: As I said, we’re always playing something different. The summer was more a tour for his record, The River, and pretty much what I did on the CD was more like color, just playing my way, not always playing, but always trying to find the right moment to interact. But the last tour was different, because we had no singer, so it was more playing-oriented, so my function was still doing the same thing, but more open compared to what I was doing in the summer. But playing with him is the greatest thing. When I finish playing with Herbie, either listening to a piano player or playing with a piano player is always hard, because I start hearing some stuff naturally, and then I realize it’s not him. Because with him, it’s always challenging. When I finish a tour with Herbie and start listening to other piano players, it’s always hard. I don’t know how to describe it. But there’s something… The only person for me that I listen to after Herbie that makes me feel the same is Brad Mehldau. I listen to Mehldau, he’s very strong, he has his own thing, but after Mehldau or McCoy or people like that, it’s very hard.

TP: You were playing solo concerts opening for Mehldau and for Roy Haynes a few years ago, in 2005, and you also played trio with Herbie and Wayne…

LIONEL: Yes, in Japan.

TP: Which must have factored into your concept for Karibu .

LIONEL: Yes, that helped me a lot. Because when he asked me for the record, I wasn’t nervous because of that trio thing that we did, so I had some ideas already of where this can go, and for my own thing, music I wrote… Like, “Lights Dark,” which features both of them. I wrote it definitely having both of them in mind. Very open.

TP: Did the title denote in any way your sense of the way they play, the contrasts…

LIONEL: Exactly. Wayne Shorter is one of my favorite composers of all time, and if you listen to Wayne’s melodies, you can sing them all day long. The harmony may be complex, but supporting the melody in the right way. For me, that’s exactly what I tried to get on that tune. The melody was very simple and the harmony can go anywhere.

TP: Last night it was my impression that you only prepared the strings once. You took out paper, covered it, and got a kalimba sort of sound. But other than that, all the sounds were extracted from the pedals and your hands. Are you preparing the guitar less now? Was that just last night?

LIONEL: I just feel like people start thinking about me in one context, but I don’t want to lock myself into one thing. Most people think about the way I play the African thing and the paper—which is great. That’s what I do. That’s who I am. But I don’t want to lock myself in just that one direction. I still want to play standards, still want to do everything, but still be me.

TP: But it seemed you were getting those sounds without preparing the guitar.

LIONEL: Oh, yes.

TP: Have you been working on that?

LIONEL: Yes, that’s something I’ve definitely been trying to do, without the paper. The paper thing gives me one sound. I want to be able to switch between the normal sound and the mute sound, so I started working on how to mute without the paper, where the sound won’t be the same, but it will be close.

TP: You were pointing to your palm. Apart from being interdependent with both hands, do you have interdependence between the muscles in each hand?

LIONEL: Exactly. That’s where I’m getting now. I can come from legato, I can go to staccato and mute, everything, without putting paper in. If I need the paper, like I did yesterday for one tune, I do it. But the rest, I can do it in a different way.

TP: When you say that you need time off to work on your concept, it would seem that when you’re on the road with Herbie, you do have a lot of time?

LIONEL: Oh, no! Because Herbie’s tour… Well, the fall tour, the last one was a little easier, but most of the tours we play five, six, sometimes nine gigs in a row in different cities, so there’s no break, meaning you have to wake up at 5. There’s no time to practice. But when I have a day off… We had a day in Turkey, in Istanbul, and some people went out. I preferred just to lock myself in and write music, because that’s the only time I have, really. But even if I go out, I always find time to write music.

TP: If you had that ever-elusive month off, how would you practice? How much is physical? How much is thinking?

LIONEL: I think definitely it would be more physical. I am thinking constantly anyway. The way I am hearing my playing, the way I want it to be is… I am getting close to the piano context, where my playing is getting harmonically supported by myself at the same time, and have the righ technique to play melody and harmony, and make them very clear sometimes, make them very confused sometimes. But that for me requires a lot of practicing. Because I have a different tuning, there’s a lot I have to learn for my own tuning, and I need time… I can hear those things in my head, but they’re not in my fingers. I need to put them in my fingers.

TP: What struck me the most when I talked to you three years ago is your patience, your ability not to do something before its time. You studied thirteen years before hitting the scene. The temptations must have been great. I’m sure there were times you were just eating noodles because you weren’t working.

LIONEL: Oh, yeah.

TP: It’s hard for people to talk about their character. But tell me a little bit. Have you always been this patient?

LIONEL: Yeah. There are two things. First, I always want to push my limit. I always want to get to something else. Even if I take a month off, even if I take six months off, I still want to find something else. The second thing is, I am always looking for new things for myself, because somehow on standards I get a little bored. I always try to find a new direction harmonically, melodically, technically, on the instrument. Now I’m less patient than I used to be. Before I knew that this is my goal, and I take whatever time it takes, I’m going to get it. Now I have more pressure, doing gigs on my own, I have two kids—so I have less time to accomplish those things. So I feel more like I don’t want to waste my time.

TP: You could eat noodles, but you can’t make them do that.

LIONEL: Exactly. But at the same time… For example, I’m here for a week. Normally I would come by myself, and that’s the perfect time for me to do something. But I haven’t seen my family for three months. So I am less patient than I used to be.

TP: But also, you’re playing with someone who is a great virtuoso, but seems not to unduly sweat over the things you worry about.

LIONEL: Yes, definitely.

TP: I wonder if that’s had an effect on you.

LIONEL: Definitely. I’ve asked him many times how he does it, and he always tells me he used to practice a lot. He told me, “I practiced for hours and hours. Of course, now I don’t practice, but I practice a lot in my head.” I practice in my head, too. But he is able to just put it out, because he has practiced for many hours and has it in his fingers. I don’t.

TP: Well, your concept is also about extended techniques. Trying to be interdependent with your thumb and fingers involves muscle memory. Herbie Hancock’s muscle memory has been there since 6. He’s not playing like Cecil Taylor.

LIONEL: Yes. He’s thinking more harmonically and melodically and different type of colors. I’m thinking of that less, but I’m thinking more about the technique, how I can divide the whole instrument like mutes, be able to make the bass strings, the four lower strings, and open the higher strings—or vice-versa—so that when you hear my playing you hear some very legato and mute at the same time. I know it’s possible. Even if I haven’t heard anybody do it, I know it is possible, because when I try, sometimes it comes out. But it doesn’t come out every time. [23 – 23:40]

TP: What music are you listening to lately?

LIONEL: Lately, mostly classical. If I go to jazz, I will listen to Wayne most of the time. But I’m listening a lot to classical lately—Ravel, Debussy, Stravinsky, all the contemporary composers. When I listen again to my heroes, Wayne and Herbie, I start hearing those elements, and lately, if I listen to Wayne, what he’s been doing to classical music and classical instruments, complete with the quartet, it’s very inspired.

TP: Do you ever go back and listen to African music, or is it something that’s just there because it was so much of your early…

LIONEL: I can’t say that I listen to it that much. But I do sometimes on my IPod… I know pretty much everything on my Ipod, but if somebody gives me some CDs or stuff, I’ll put them on. I have some tapes from back home that, when I feel like, I listen to, but it’s mostly pure traditional, just percussionists and voice or just percussion. I listen to those things. The last six months, I haven’t.

TP: You did the concert with Richard Bona, which was a very interesting concert.

LIONEL: The first time I played with him was with Jeff Tain Watts, trio, at the Jazz Gallery. Then he invited me to the Montreal Jazz Festival, where he was the guest for a week. From that, we said, “Well, maybe we should play a duo concert.”

TP: It was interesting, because your personalities are so different.

LIONEL: Oh yeah. We’re very different. But it works because the African element is very strong, we both know the rules… That concert for me, I had fun, because it was two different musicians with their own thing but at the same time have something in common. We didn’t have to explain. Usually, when you play that type of music, you have to explain to people, “This is one.” But with him… [LAUGHS] We have the same one! Usually when I play with people, they have their one, I have my one, and it doesn’t matter—it works. But with him, the one is the same, because we feel it the same way.

TP: One thing you were doing three years ago that you don’t do so much now, because of time constraints, was playing a lot more on the New York scene. You were playing with Avishai Cohen’s African project, Yosvany, so many people.

LIONEL: I miss that, I have to say. The main reason I moved to New York was to do that, and I knew that if I started getting busy it would be hard to do it, and plus, once you start playing the clubs, playing a gig at the Jazz Standard under your name, they don’t want you to go back and play at the Jazz Gallery under your name. Those little things. I didn’t really think about it before, but now everything is contract. You have to wait six weeks to play. So it makes it hard. That’s one thing. The second thing is I’m not there any more like I used to be. Between Herbie’s tour and this I was home for a week, and after here I go home for not even a week, and then I’m out again to play in Boston with the Gilfema project. Then I’m going home, taking ten days, to see my parents in Cotonou. But when I’m in New York, I would love to do it. But also, when I’m there for 3 or 4 days and I haven’t seen the family for three months, it is hard to tell your wife, “Ok, I am going into the city to play.”

TP: Then also, you miss so much with your kids.

LIONEL: Exactly. I miss that, definitely. So I try to stay home when I’m home.

TP: But in 2009, you won’t be out so much with Herbie. You’ll be touring Europe in March and April with the Lionel Loueke Trio.

LIONEL: Yes. In February we go to New Orleans for some dates for ten days or two weeks, and all of March we’ll be in Europe—Spain, Greece, U.K. Then back in the States touring in April as well. So we start getting busy. Miles Winston, my agent, is keeping me busy.

TP: Is Gilfema going to do things in 2009?

LIONEL: No. We started with Gilfema, and now Gilfema is kind of dying. The last CD is very much because we owed an optional CD to Obliq Sound. We had to do it. We don’t have any more projects.

TP: Is that because people are more interested in your name and less in your name, or because they’re doing other things?

LIONEL: Everybody is busy. When they are not working with me, Massimo is working with Ravi Coltrane or Paquito. So they’re all busy doing their thing, and they all have their own CDs, so that they have their own projects. In May we’re going on the road under Ferenc’s name with other people. So they have their own projects as well.

TP: You don’t need to be so collective because everybody…

LIONEL: Everybody is busy. And the thing is, if I cannot keep them busy, they have to work. One thing about those guys is we really love each other besides the music. Even if I’m on the road, we call each other. It’s a real family.

TP: I can see that at the dinner table. Your daughter was hanging onto Ferenc with spaghetti sauce on her.

LIONEL: Exactly! We hang a lot together. That’s the thing, and I always see it on stage. That comes out in the music every time we play.

TP: You’re someone who thinks in the long term. Probably ten years ago, you half-envisioned what you’re doing now, maybe not that you’d be on the road with Herbie Hancock…

LIONEL: Hoping.

TP: Where do you see yourself five years from now, when you’re in your forties?

LIONEL: There are a lot of different projects I would love to do. I don’t want to lock myself in one…

TP: You had a string project a few years ago. I haven’t seen that yet.

LIONEL: That’s coming, and it will definitely be the result of all of the classical things I’m listening to now. Something I want to write for string quartet, plus the trio. That project definitely will come out.

TP: On the model of Wayne and Imani Winds.

LIONEL: Yes. I want to find guys who can at the same time improvise in a way that there’s a real interaction between the trio, or duo, or whatever it is going to be, with the quartet. Because what I hear most of the time when people do that project, they write something specially for the quartet, and then hear the quartet comping. I don’t want that. I want it to be no one is comping for anyone.

I’m also thinking to do another African project, but with the same context. It won’t be classical instruments, but it would be African instruments.

TP: You’d orchestrate the African instruments.

LIONEL: Yeah. It would be kora, kalimba, djembe… I want to do that project just with the acoustic guitar.

TP: You’ve become very accustomed to chromatic playing, and African instruments aren’t chromatic, so the orchestration would be the challenge.

LIONEL: Exactly. My job will be to find a way. Because one thing I don’t want to do when I use those instruments (that’s why I don’t use them that much) is to have just one scale and one sound that everybody recognizes. That’s one thing. But I’ve started hearing some young African musicians, especially in Paris, who start having like a chromatic kora. That’s something I’ve been looking for a long time, somebody trying to play those instruments in a different way… A friend of mine now is playing chromatic balafon.

TP: So it’s a new instrument.

LIONEL: It’s a new instrument, because it’s against the tradition, basically. He cannot play that in the village! But that’s the way I’m seeing African instruments anyway. One thing is to keep what’s already done, what’s there. But now I think it’s time for the young musicians to take it to a different level.

TP: You’ve led me to the last question I want to ask, which is a complex question, because it has to do with the way you construct your identity as a musician. Which is to say: you were born in Benin, you have ancestors in the village, and your parents are urban intellectuals from the post-colonial period.

LIONEL: Yes.

TP: One thing I want to know is the response that your music receives in Africa, if people in Benin are hearing Karibu or your other records, what they think of it, and so on. Then also, how you address the different attitudes or mentalities that are expressed in African cultures and Western cultures, which operate on very different suppositions, have different core aesthetics behind them.

LIONEL: People in Africa start hearing my music. Every time I go to Benin, I always play a concert, so they start getting familiar with it. But there is always a new element for them. I did a tour last year, I think, in 15 countries in Eastern Africa, just solo guitar. I went to Kenya, Tanzania, and down. But the reaction of people, they see the African element in my playing, but then they see the element they are not familiar with. So just like when I play in Europe or in the United States, you hear something that’s familiar, it’s the same thing going on in Africa when they listen to it. They are not that familiar with it, but they can find their way to what I’m doing with some of their limits—it’s new for them. I like it that way, because my interest is to bring something different as well. I don’t want to do something that is already done for both worlds.

The second element: The way we play in Africa, I never lost that. How the music is related to everyday life and the context, and what you play is definitely to your heart, first of all. When I studied, I almost… In my life, when I was a student… I mean, I’m still a student. But when I was in music school, at one point I almost lost that, started becoming very intellectual in everything I’m playing, because I didn’t understand them, I wanted to understand them, and my heart was not speaking like it should be. But the good thing is, I found the right moment to say, “Wait a minute, I don’t want to lose this natural thing I have from the beginning without understanding anything about harmony.” So I found my way to go back and.. Anyway, I’m never going to be able at this point to be the musician I was before, even if I was the most organic musician ever at that time. But now I can’t be that organic even, because I have some new elements.

TP: You opened the box.

LIONEL: Exactly. I just don’t want to lose that. Anything I’m doing has to come from inside, deeply inside.

TP: As a young person, what were the first things you learned in the intellectual history of Western culture. Your father is a mathematician, your mother is a schoolteacher, they grew up under colonialism. What are some of the core principles that were fundamental to you.

LIONEL: For me, it definitely was Communism. I grew up seeing my mom making…I don’t know how they call it in English… They call it defilés, when you see the military walking, like a march, and you see all the teachers, every… I was a kid, I was doing that, too. If I go to the movie theater, I have to stand up and sing the revolutionary…

TP: The Internationale.

LIONEL: Exactly. The funny thing, sometimes Ferenc and I make a joke and we sing. He sings it in Hungarian and I sing it in French. The same melodies. We both grew up under Communism. So those were my first…

TP: I didn’t know Benin had a Communist government.

LIONEL: Oh yeah. So those are the first things I learned about Western culture.

TP: Interesting. You seem more like a son of the Enlightenment than…

LIONEL: I found my way out quick. I think Communism definitely has a good point, but there’s a lot of things that didn’t work with my…

TP: Well, you have to conform to the program, among other things.

LIONEL: Yes. It wasn’t easy. That’s actually how I started music. When I was in high school, we had a band, and at the same time we had two hours per week, every Friday to play music, or, if you choose, to do painting—different activities. But they all related to Communism. Before you studied, you had to sing and do the military march and everything. Every day. So if I go to the classroom, before I get in the classroom, you have to be in line, sing, do the military march, take your seat…

TP: Were they Maoist?

LIONEL: Yeah, it was Maoist.

TP: So when you got to Paris and saw the French intellectuals who’d been Maoist in the ‘60s, you might have had some thoughts about that.

LIONEL: Yes, exactly. I don’t want to get into that. But once I got to Paris, Communism was already… It was a different story. I went to Paris in ‘94. So it was gone!

TP: Was the regime interested in retaining traditional culture or were they trying to eliminate traditional culture?

LIONEL: Well, they were confused. For the traditional singers and musicians, the government was asking them to compose using those lyrics. So all they were singing was revolutionary words…

TP: But with the same rhythms and melodies.

LIONEL: Yeah, it still was traditional. But then we had the other side where we start learning all the revolutionary songs from Eastern Europe, and I know many of those and play them. I could do a record! I still remember. It’s amazing. [LAUGHS]

TP: Do you have a contract for more recordings with Blue Note?

LIONEL: Yes. I think I have four.

TP: So one hopefully will be the string project you described.

LIONEL: Yes. One hopefully will be a string project. One will be the same project with African instruments. I’d also love to do a record just playing standards, the way I hear them, but swinging. Even if it’s swinging in 7 or 9 or whatever, it will be swinging.

[END OF CONVERSATION]

************

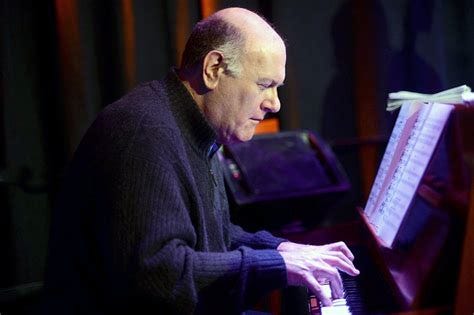

Chick Corea-Lionel Loueke, Blue Note (Sept. 26, 2017) – (Third Edit):

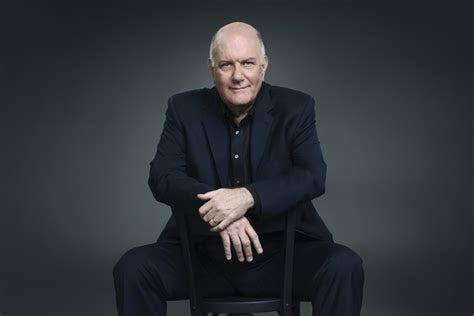

It may well be that no jazz musician has ever conceived, composed music for, led, and performed with more top-notch bands than Chick Corea. Corea’s latest, a co-led septet with drummer Steve Gadd that is presented on Chinese Butterfly (Stretch/Concord), lives up to his high standard. Last February, before the group had ever played before an audience, he convened the personnel—Lionel Loueke, guitar and vocals; Steve Wilson, alto and soprano saxophones and flute; Carlitos Del Puerto, acoustic and upright bass; and Luisito Quintero on an array of percussion instruments—to record the album. They reassembled in late August for a brief tour of Japan, then entered Manhattan’s Blue Note on September 19th for a two-week residence before embarking on a two-month sojourn that traversed the U.S., South America and Europe.

For the first set on September 20th, patrons packed the Blue Note’s 200 seats at $85 a pop. Many looked old enough to have tracked Corea, 76, and Gadd, 71, since the early 1970s, when Gadd propelled the first electric edition of Return To Forever, then such signpost Corea albums as My Spanish Heart, The Leprechaun, The Mad Hatter, Friends, and Three Quartets. They remained fully engaged through a 90-minute performance in which the members—inspired by, as Wilson enthused, Corea’s “bottomless well of imagination” and timbrally expansive, ever-morphing percussion discussion between Gadd and Quintero—fulfilled their collective and soloistic functions with panache, cogency and imagination.

“Chick’s music sort of plays you,” Gadd said the following day. “His stuff brings lots of musical ideas to mind. We didn’t sit down and write the things together, but we’re always trying to come to an agreement musically, and when we do, it feels my input is making sense. It’s amazing to listen to him every night. He’s constantly trying to raise the bar. I’m still as excited to play with him now as I was when we did it years ago. It’s Chick Corea!”

Not least among the evening’s pleasures was the opportunity to witness Loueke interact with Corea in real time, and to springboard off his melodies. “Lionel has that African triplet feel, which I call the ‘source triplet’,” Wilson said. “It’s very different than what we deal with here, and Chick plays off it a lot. It brings a whole other layer of rhythm to Steve’s groove and pocket.”

On September 26th, before the first show, Corea and Loueke joined Downbeat in the Blue Note’s top-floor offices to discuss their evolving relationship.

* * *

DB: Lionel is the newest member of your musical family.

Corea: We are newly acquainted in the past year. I’d heard Lionel with Herbie, then started listening to his solo records. I was attracted to his wide range, so he immediately came to mind when I was thinking about this band,. Then I thought we should make sure we groove together. I have an interesting relationship with guitar players. Both keyboard and guitar are chordal and comping instruments. I lead the band around with my comping, so the guitarist and I have to coordinate. And this is a bit of a commitment—we’re going to make a record, we’re touring. Lionel came to my place—one day we jammed together; the second day we did my online music workshop. That’s when I wrote the basic tune to “Serenity”—we played those changes and did it that first time, just reading the chart. After that duet, I thought, “This is going to work great.” And it has. The parts seem to fall into place naturally.

I am going to assume, Lionel, that you’ve listened to a lot of Chick Corea during your lifetime.

Loueke: Yes. [LAUGHS]

Describe your experience at that initial meeting.

.

Loueke: I was nervous. At the same time, I told myself this is about having fun—be myself, don’t get stressed. And once I got to the maestro’s place, he made me feel so comfortable. When it’s like that, I can deliver and we can have fun. As he said, there’s a natural chemistry. He listens so well, and makes whatever I’m doing sound better, which is the quality of any great musician.

Chick, Isn’t “Wake-Up Call” your arrangement of an improvisation of Lionel’s at the workshop?

Corea: I think I started an improvisation, so then we did one, and then I said, “Why don’t you start something?” So Lionel began this line, and we improvised with that idea. It stuck in my mind. I asked Bernie Kirsch, my sound engineer, to give me a copy of what we’d just recorded, and it seemed like a great tune. So I put a little structure on it. I didn’t do much to it…

Loueke: You did magic to it.

Corea: When we recorded it in the studio, we went over the two or three little sections I wrote, and then we threw it down once. We didn’t get to the end. Then we regrouped and threw it down a second time, and improvised without instructions for 18 minutes. It came out really nice.

Lionel, you’ve been expanding out from your trio with different bands. Apart from your work with Herbie Hancock, there’s a new duo recording with Kevin Hays on piano; another new recording with an Australian band, The Vampires; and another new recording with the Blue Note All Stars. How do these experiences filter into what you do in this band?

Loueke: Every time I play with different musicians, I try to keep it fresh and learn something. As I move from project to project, from concert to concert, there’s no boundaries, no preconception about what I’m going to play. Then the magic happens—or not. When I’m playing, I’m super happy. By the time I put down my guitar, either I’m happy or not, but at least I gave myself that freedom of trying to discover new things every time.

Corea: I have a question for Lionel. You’ve developed a guitar technique, make a bunch of different sounds on the guitar, and you’ve developed a rig. What’s your history with the instrument? How did you come to that sound?

Loueke: Actually, from 9 to 17, when I lived in Benin, I played stick percussion and hand percussion. I was a dancer. I played a lot of traditional music. When I started playing guitar, I put all that African heritage on the side because I was so interested to learn jazz. I’d listen to you guys and think, “What are they doing? What is this?” But even so, when I went to Berklee, my peers, my teachers were telling me I already had my thing, but I wasn’t hearing it because I was trying to play like them. At some point, I decided to listen, and I realized I’d learned something from all those years playing percussion—that it comes out on the guitar. I’m like a frustrated percussion player.

Corea: So am I. I’m a frustrated drummer.

Loueke: I used to play the talking drum. I was looking for a way to make the guitar sound like a talking drum. I found a whammy pedal that would let me play one note and use to my foot to bend it, to change the pitch. Back then, I was playing with a pick, and I thought playing with fingers would give me more polyrhythm.

Corea: How many fingers do you use to pick?

Loueke: I use four.

Corea: So you have four picks instead of one. The range of stuff that Lionel gets is one of the amazing things about his performance.

This is a drum-oriented band, incorporating Brazilian, Afro-Cuban, West African and Spanish elements. Chick has a long history playing in Afro-diasporic contexts, going back to your time with Mongo Santamaria in 1960. Lionel is from West Africa, and, as he said, he was “trying to play like them.” It’s as if you’re arriving at a similar spot from opposite directions.

Corea: Absolutely. The Cubans around Mongo in ’60 or ’61 kept their African heritage very deeply. I felt Cuban. I was learning about Mongo’s religion, about his way in the music. But we were all in New York. I lived here from 1959 to 1976. I connected musically and spiritually with all the different musicians. Every time I come back I’m amazed by the city as a microcosm of the Planet Earth. All the cultures come here and mix. The city sort of represents what we like to do in the band, which is draw from all these different cultures and influences.

In my mind, jazz is a spirit of creativity. As communication has gotten quicker and tighter with the internet and airplane travel, it doesn’t take a century to learn about Bach’s music, or whoever’s music. It’s all available right there. [points to his iPhone.] Creative music happens in every culture. What happened in this phenomenon called America is that Africans and Cubans and Europeans came, it got mixed up, and people like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington come around, and then it coalesced into something we call “jazz.”

Lionel, you spent something like 11 years of formal study before entering the fray as a well-prepared professional musician. How did arriving in New York affect you?

Loueke: Well, I thought I was prepared. In New York, the range is huge. There’s so much to learn, new ideas, new talent, so much going on that people don’t even point their eyes or ears into. Sometimes I’m like, “Man, is nobody hearing what I’m hearing? Come on. This is so fresh.”

Corea: I think it’s about a 10- or 20-year lag in understanding. Something new comes out, and then the public starts to hear it. At first they think it’s weird. The critics pan it. Then the artist keeps going, and after a while nobody goes, “That’s weird.” Stravinsky’s music, Stockhausen’s music, Monk’s music, Cecil Taylor’s music, Trane’s music—they’re all classic now.

Loueke: Everything is here. For music, there’s no place like New York. It’s so cosmopolitan. There’s a healthy process of learning from each other that you don’t get elsewhere. My first weekend in New York, I met Tain. I met Roy Hargrove. There’s only one place that can happen.

Corea: I think you ought to name the issue, “New York is the world.” I started listening to my dad’s 78 recordings of Miles Davis playing with Bird in 1947, when I was 6. My dad played trumpet, and he tried to play like Miles. Then, in 1951, me and my one jazz friend bought Dig, Miles’ album with Jackie McLean. Following Miles’ records after ’51, with Horace Silver, or with Monk and Milt Jackson, I saw that he was sort of the New York of musicians. If New York collects all the musicians of the world, Miles collected all these special musicians. So from early in high school, I had my sights set on New York. In my senior year, I went to one-third of the classes. My parents had bought their first car, a used red Mercury Cougar convertible, and on weekends I’d drive it to New York and go to clubs.

Lionel, did you listen to a lot of records as a young guy in Benin?

Loueke: Few records, because it was hard to get them. But I was really into guitar players. Somebody would make a cassette, and I’d transcribe by ear whatever I was hearing. You’ve got to put it into context. I had no connection about harmony. I couldn’t explain to you what II-V-I is. I could hear it, but I couldn’t name it.

Corea: Who were you listening to?

Loueke: Wes [Montgomery]. Tal Farlow. Kenny Burrell. Barney Kessel, Johnny Smith. I found out about most of those guys after I moved to Paris. I’d get the notes, but I had no idea who was playing or what the tunes were. The first concert I played was just my cassette player, and I played exactly the transcriptions.

Corea: I did the same thing. I had a trio in Boston with this drummer, Joe Locatelli, and a bass player. I’d transcribed a bunch of Horace Silver tunes—not only the tunes, but some of Blue Mitchell’s trumpet solos and all of Horace’s piano solos. I got gigs, and I would play those solos on the piano—and then play my own stuff.

Loueke: I couldn’t do my own stuff, because I had no clue. I just played back.

Your 2017 CD, The Musician, documents a 2011 residence at the Blue Note when you played with 10 different bands. In 2016, you did 8 weeks there with 15 different bands, including one called Experiments in Electronica, in which you improvised tabula rasa with Marcus Gilmore, Taylor McFerrin and Yosvany Terry.

Corea: I like that way of making music, having no theme, no preset plan—just go up and see what happens. It’s an adventure. The more people involved, the trickier it gets. You can do it with a duet not so bad. Well, that’s what Lionel and I did. We were just fooling around. I have in mind to do more improvisation like that.

Loueke: The true magic happens in the unknown. Maestro Chick has written things that will stay with people forever. While we’ve been talking, a saxophonist on the street, downstairs, has been playing “Spain.” We sometimes play “Spain” as an encore, and as soon as we start the melody the whole crowd goes, “Whoo!” That’s what it’s about—composition, and then the development of the composition, which is the unknown. Every day is different.

Corea: Unless you’re copying something, the unknown is where the composition comes from. What is the imagination? It’s the unknown. You remember a certain line, or a certain sound or melody, or whatever gets said—so now that’s your song. That came from a free improvisation. Fortunately or unfortunately, when an audience hears a group freely improvise without set melodies, they have to be savvy to the interaction of the musicians, because they don’t hear anything familiar. We try to balance our improvisation with the songs, because we don’t like to leave the audience wondering what we’re doing.

The Experiments in Electronica group also addressed the intersection of technology and music, just as Lionel has done in emulating the sound of a talking drum with a whammy pedal.

Corea: A lot of musicians use MIDI protocol where, with a drumstick or a key or a guitar pluck, you can trigger a sound and its volume and duration to a synthesizer or another instrument. That’s part of what we call technology. But to me, a wider definition is the instrumental technique used to produce the effect. There’s a way you bend notes, a way you move your hands, there’s posture, the kind of instrument you choose—all kinds of technology and “science” goes into that. You train yourself to press a button here, a pedal there, your hand goes like this, and this sound comes out.

Loueke: Music is sound. Sounds develop through the years. But the key is: How do you choose this one at this moment? If you have only one sound, no problem. That’s what you get. But when you have many sounds, yeah, you can use them, but you’ve got to find them. Which is very hard. When you hear them, it’s now. Then it’s gone.

Corea: It’s a lot of triggers. Do you know the old joke about Johann Sebastian Bach?

Loueke: No.

Corea: Someone asked him, “How do you do it?” He said, “I press the right key at the right time.”

You’ve mentioned that every interviewer asks you about Miles Davis, and that perhaps your most consequential lesson from that experience was his insistence to “play yourself.” It’s no cliche to say that you apply that principle to the max with this band.

Corea: I try to apply that in life. I see that great art is made when the artist is free to try whatever techniques he wants, and combine things any way he wants. That makes life interesting and a joy. I try to live that way as best I can. I don’t always succeed. I would like others to acknowledge my freedom to be myself and try new things any time I want to, and I try to treat other people that way. Then there’s fairness and balance in life.

Loueke: The way you live comes out through the music somehow. It took me a while personally to learn that and say: Maybe I should look into MY life. That represents who I am, and music is just part of who I am. That’s what I try to do. Like the Maestro said, if I can live better, I’m sure whatever I do will be better. It could be music. It could be anything.

***********************

Lionel Loueke Blindfold Test – 2009:

- Mike Moreno, “I Have A Dream” (from THIRD WISH, Criss-Cross, 2008) (Moreno, electric guitar; Kevin Hays, piano; Doug Weiss, bass; Kendrick Scott, drums; Herbie Hancock, composer)

I think somebody definitely from my generation, and has his sound. I can hear, of course, a little Kurt Rosenwinkel influence. But if I’m right, I think it’s Mike Moreno. He has his sound; it’s a really lyrical, warm sound. I love it. Actuallym, the drummer was the first one who caught my attention, not only in the feel, but the way he tunes his drum set is very unique. But the sound of each tone and the feel was so familiar—and now I can see it’s Kendrick. That’s my boy! I love his sound. I love the tune, too, but I don’t know it. I don’t think it’s his original. Mike is definitely one of the great players of this generation. He’s been working with different musicians, especially here in New York. There are only a few guitar players who I heard a lot about, and he’s definitely one of them. 4 stars.

- Russell Malone, “Little Darlin’” (from Ray Brown, SOME OF MY BEST FRIENDS ARE…GUITARISTS, Telarc, 2002) (Malone, acoustic guitar; Brown, bass; Geoff Keezer, piano; Kareem Riggins, drums)

I can hear a huge influence of Russell Malone in this player, because of the vibrato at the end of each note. But I don’t think it’s Russell, because I don’t hear the depth, the personality, unless it’s Russell when he was younger. The vibrato of each note, especially at the end of the phrase, makes me feel that there’s also a huge influence from Django The sound reminds me a lot of Jim Hall—he’s placed the mike in front of the guitar. Jim Hall is the master of that. The bass sounds great. That’s a hard tempo to play on! Those medium tempos are the hardest. Also the space between the phrasing is great. 3 stars.

- Pat Metheny, “Let’s Move” (from DAY TRIP, Nonesuch, 2007) (Metheny, electric guitar; Christian McBride, bass; Antonio Sanchez, drums)

I can tell right away that this is Pat Metheny. He has definitely his own sound. Whoo! That’s a hard tune—just the head is hard to play! I know Pat not only has a great sense of melody, but also has great chops, but I didn’t know his chops were this huge! That exceeds even his standards. That bass player has crazy technique that I don’t hear that often, especially from acoustic bassists. I think it’s someone I recorded with not too long ago with Angelique Kidjo, Christian McBride, just from that ability to play so fast and so precisely. I could also recognize Antonio Sanchez from his sound; the sound of his drumset is unique, and his playing is clear and precise. 5 stars.

- Romero Lubambo, “Loro” (from Trio de Paz, SOMEWHERE, Blue Toucan, 2005) (Romero Lubambo, acoustic guitar; Nilson Matta, bass; Duduka DaFonseca, drums)

I think that’s Romero Lubambo. No, it’s not him. Romero doesn’t play with that kind of aggressive attack. Well, he’s playing on a steel string, so maybe that’s why he’s playing so aggressive. It doesn’t sound like someone who’s used to playing on that instrument. The personality isn’t strong, like someone I’d recognize by one phrase or two phrases. 3 stars.

- Mark Ribot, “Fiesta en El Solar” (from Y LOS CUBANOS POSTIZOS, Atlantic, 1998) (Ribot, guitar; Anthony Coleman, keyboards; Brad Jones, bass; Roberto Rodriguez, drums; E.J. Rodriguez, percussion; Arsenio Rodriguez, composer)

That sounds like an African guitar player, like from Congo or Zaire. Oh, the way the rhythm section is playing, those are not Africans. Is it Santana? No, it’s not Santana’s sound. It’s not Ali Farka Toure. No. What makes me think it’s African is the sound of the guitar. But it doesn’t make sense that an African would play with that rhythm section, and then, it’s a tres. I don’t know any Africans who play tres. The guitar player is probably Cuban. In Africa there’s a few old guitar players who have that tres sound with 12-string guitar or another guitar with different effects. Nothing sticks to me, telling me a strong personality is playing. A lot of different cats from Cuba could play that. 3 stars.

- Julian Lage, “Clarity” (from SOUNDING POINT, EmArcy, 2009) (Lage, acoustic guitar; Ben Roseth, saxophone; Aristedes Rivas, cello; Jorge Roeder, bass; Tupac Mantilla, percussion)

This piece is beautiful. It sounds like something I’ve heard before; I’m not sure if it’s an original composition. But the arrangement is outstanding. The guitar player has a big influence from Pat Metheny, but not a cliched influence, not doing Pat Metheny’s licks. I hear some influences, but he’s being himself. He’s not trying to play like somebody. I can hear the sense of melody. He also gets close to that Jim Hall sound with the mike in front of the hollow-body guitar. The only person I can think of is the young guitar player who played with Gary Burton. I don’t remember his name… Julian Lage. 5 stars just for the arrangement; 4 stars for the whole thing.

- John Abercrombie, “How’s Never” (from Gateway Trio, HOMECOMING, ECM, 1994) (Abercrombie, guitar, composer; Dave Holland, bass; Jack DeJohnette, drums)

That’s Dave Holland playing that bassline; not many other bass players can do that kind of odd-metered bassline. That’s John Abercrombie. He’s easily recognizable because of how much he uses the chorus pedal—I can recognize him from that sound. Because he uses the chorus and the way he phrases, he has a long sustain sound. He plays very legato, but at the same time, every time he picks a note, it’s very percussive. Of course, Jack DeJohnette is the drummer. 5 stars. I love the tune.

- Lage Lund, “Quiet Now” (from EARLY SONGS, Criss Cross, 2008) (Lund, guitar; Danny Grissett, piano; Orlando LeFleming, bass; Kendrick Scott, drums; Denny Zeitlin, composer)

I have a few names in mind. First, I like the tone of the instrument. The tone of the guitar really touched me. I love the sound of it. It reminds me a little bit of Bireli Lagrene, but at the same time I have some doubts. The other person it reminds me of is Adam Rogers, who plays with Chris Potter and used to play with Michael Brecker. It’s neither of them? I like the tune, and I love the player. There’s a lot of medium range in the sound, and I like it, and I can hear… At the beginning of the tune, I could hear…I still don’t know… it feels like he was playing with fingers, so I heard those notes very close to the piano. Later on, I hear, of course, he was playing the pick. Great technique. Great sound. Great feel. But it’s not Bireli Lagrene, it’s not George Benson either—I don’t know. 4 stars. [AFTER] Actually, I did think about Lage for a second, but then I said no.

- Bela Fleck-Djelmady Tounkara, “Mariam,” (from THROW DOWN YOUR HEART: TALES FROM THE ACOUSTIC PLANET, VOL. 3, AFRICA SESSIONS, Rounder, 2009) (Fleck, banjo; Tounkara, guitar; Alou Coulibazy, calabash)

That sounds African for sure. I can’t even tell…that’s from… Are most of the musicians from Mali? I hear the calabash sound. The guitar player, I don’t know if he’s African. Could it be Leni Stern? Not Leni? I don’t know. It’s a beautiful piece. That’s definitely Mali for me. That style of guitar playing…almost everyone plays like that in Mali for me. The other string instrument reminds me of…if I’m thinking of an African instrument, I think of n’goni. But even though it reminds of n’goni, it sounds more like a banjo. 3 stars.

- Bireli Lagrene, “Sur La Croisette” (from SOLO: TO BI OR NOT TO BI, Dreyfuss, 2006) (Lagrene, acoustic guitar, composer)

Whoa! Whoo! Man. Again, somebody with a big influence of Django Reinhardt. At the beginning, I was thinking of one of the Latinos, that guy from Venezuela, but the chops… I’m probably wrong, but the person I know who plays with that energy and freedom is Bireli Lagrene. Bireli is one of the cats who has not only the great technique, but the ideas. It definitely reminds me of him. The flowing of the ideas. There’s always something coming. Especially for what I just heard, what I like is the spontaneity. I don’t hear the phrase coming, if it’s going to be short or long. And I like the sound from the fingers on the strings. It’s very, very intense. 5 stars. [AFTER] Whoo! Bireli… Everything I said makes sense, especially the Django influence. People don’t know too much about Bireli, especially when he goes out of the Django playing. The Django influence obviously is there, but this is one of the guitar players that can carry so much different territory, and just go, like I said, from one place to the other. I don’t hear any… There’s no barrier. He can just go from scratch to anywhere he wants, without having something holding up technically or harmonically. He’s a real genius.

- Nguyen Lê-Paolo Fresu, “Stranieri” (from HOMESCAPE, ACT, 2006) (Lê, electric guitar; Fresu, trumpet)

That’s a hard one for me. It sounds like a band from Europe—the trumpet, the effects on it and the groove reminds me a little bit of Erik Truffaz. The guitar playing at the beginning…I can hear a little bit of some Indian sound, or, so I was thinking about John McLaughlin. But then I said, “no, it can’t be John.” It sounded like three musicians. I like it. I like the groove and I like the ambiance. The guitarist reminds me of a cat in Paris named Louis Winsberg, but I don’t think it’s him. 3 stars. [AFTER] Yeah, it had something European. The effects on the trumpet and the groove. I don’t hear that a lot here in the United States. You may hear some groove, but then when you hear the trumpet, maybe they put some effects, but not that much. The guitar, I thought this guy is Indian or some… That’s what brought me to Louis Winsberg, who is in Paris. Nguyen Lê is in Paris, too. They have a similar sound, but not the phrasing.

- Pat Martino, “Full House” (from REMEMBER, Blue Note, 2006) (Martino, electric guitar; David Kikoski, piano; John Patitucci, bass; Scott Allan Robinson, drums; Daniel Sadownick, percussion; Wes Montgomery, composer)

I’m 90% sure that that’s Pat Martino, just by the phrasing, the articulation, and the sound. At the beginning, anyway, that was a Wes Montgomery song, “Full House.” I was thinking, man, this could be one…from the groove, it sounded like it was going to a funk kind of thing. So I started thinking about people like Ronny Jordan, but then I realized it’s not going there. It’s not the same technique either. So yeah, it’s Pat Martino. 5 stars. Pat Martino is one of the greatest guitar players I have ever heard in my life. Most of us learned from him at some point. I remember transcribing his solos. When most people think about Pat Martino, they think about a lot of notes. But when I hear him, I don’t hear just notes. I think he has a unique approach to combine the notes and the technique—the technique is always amazing.

************

Lionel Loueke (DB Article):

“I wish I could find time to go away for six months and work,” says Lionel Loueke. “Things weren’t clear before, but now I know exactly what I want to work on. I just need the time.”

Time was in short supply for Loueke in 2005. The Benin–born, Brooklyn-based guitarist, 32, toured with Terence Blanchard and Herbie Hancock, opened for Brad Mehldau and Roy Haynes in Europe with solo recitals, and sidemanned at workshop-oriented New York venues like the Jazz Gallery, 55 Bar, and Fat Cat with emerging artists like Gretchen Parlato, Yosvany Terry, Jeff Ballard, Jason Lindner, Robert Glasper, and Avishai (trumpeter) Cohen, and established stars like Jeff Watts and Richard Bona. He also worked increasingly with a collective trio, which recorded the eponymous Gilfema (Obliqsound).

This disk and the more abstract solo recording In A Trance might cause an outsider to wonder exactly what Loueke finds lacking, for each document reveals his singular ability to transform his nylon-string, hollow-bodied, electrified acoustic guitar into a sort of virtual, real-time Afro-Western orchestra. He writes songs in Fon and Mina dialects, sings them with a resonant tenor voice, and improvises on the melodies, scales and rhythms with cat-like, off-the-grid phrasing and up-to-the-second harmonic progressions. He articulates his lines with self-invented fingering techniques, preparing the strings to elicit the timbres of such indigenous homeland instruments as the kalimba, kora, and djembe, and conjures phantasmagoric orchestrations with real-time looping, executing it all with enough virtuoso authority to bliss out the most demanding guitar-head. King Sunny Ade meets Pat Metheny meets Derek Bailey might be the Hollywood pitch.

The son of a mathematics professor and a schoolteacher, Loueke learned traditional rhythmic patterns orally in the village of his grandfather, a singer. As a teenager in Cotonou, Benin’s port and largest city, he emulated his guitarist older brother. “We were repeating phrases by people like Sunny Ade and Fela,” he recalls. “But at the same time I was thinking about how to get the sound of the kora or kalimba, which are not chromatic, on the guitar. I got involved in Occidental music playing Rock and Blues. At first, I thought everything was just part of the song, because in Africa you sing, then you play, and then you have the verse. When I discovered they were improvising, I became curious. The first time I heard B.B. King, the way he bent the notes reminded me of a three-string instrument in the north of Benin. I could hear where it came from.”

Eager to expand his horizons, Loueke matriculated at the National Institute of Arts in Ivory Coast, where he studied classical guitar and ethnomusicology. “I wanted to write music and I wanted to study jazz,” he says of his systematic path. “I didn’t want to go from Ivory Coast to the States because I had the language barrier.” There followed four years of jazz studies in Paris, another three at Berklee, and two years at the Thelonious Monk Institute. In 2003, after 13 years of formal education, Loueke felt sufficiently prepared to enter the fray.

“All those young, well-known guys have their own way to play and don’t sound like anybody else,” Loueke says of his New York cohort. “That’s probably what Herbie and Terence and Wayne like about my playing. It doesn’t sound like Wes Montgomery or Pat Metheny or John Scofield. You may like it or not, but it’s different. They’re looking for people who are not afraid to try different things and be themselves.”

Though he continues to find stimulation in New York’s multicultural, group-hopping scene, Loueke intends to focus on Gilfema, comprised of Swedish-Italian bassist Massimo Biolcata and Hungarian drummer Ferenc Nemeth, his classmates at Berklee and the Monk Institute. “I’m at a point where I can call any well-known musician for a gig,” he says. “But there aren’t that many band sounds in New York, and I’m hoping to play more with the same guys. I believe you create a concept by playing with people every day, and not always different musicians.”

To make it happen, he’s prepared to take his time. “I’m pulling together my harmony and the rhythms I want to develop,” Loueke says. “I’m doing it naturally, but it’s slow. If I can have a break, I’ll work on organizing the concept.”