Federal immigration agents detained three people and deployed chemical agents at multiple locations around E. 34th Street and Park Avenue in Minneapolis’ Powderhorn neighborhood Tuesday morning. At least two were observers and not the target of immigration enforcement operations.

Around 9:40 a.m., community response networks began sending alerts about Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) door-knocking at E. 34th Street and Park Avenue. By 10 a.m., a crowd of over 100 observers had gathered, confronting agents at multiple intersections.

Among the detainees was a woman who was forcibly removed from her vehicle after agents smashed her passenger-side window.

In a video taken by Sahan Journal, the woman can be seen arguing with agents prior to being grabbed by multiple agents and carried to agents’ vehicle. The woman can be heard shouting that she is disabled and on her way to a doctor’s appointment that ICE was obstructing. Prior to the detention agents had instructed her to drive away.

Shortly after, another observer on site was tackled and forcibly put in agents’ vehicle as well. According to state Rep. Aisha Gomez, DFL-Minneapolis, who was present at the scene, agents pushed the man’s head into the concrete prior to carrying him away. Gomez also said that agents were physical with her as well.

“These officers have obviously not had the basic law enforcement training,” Gomez said. “I was shoved with no verbal communication whatsoever.”

Andy Larson, a south Minneapolis resident who was out observing ICE activity Tuesday, told Sahan Journal that one protester kicked out the taillight of an ICE vehicle and was tackled to the ground up the road on Park Avenue and E. 36th Street.

“It was a really good kick,” Larson said.

The protester managed to escape ICE agents, Larson said. ICE deployed chemical irritants and shot pepper balls into the crowd and fled the scene.

According to Sahan Journal photojournalist Chris Juhn, a Hispanic man was also visible in the back of one vehicle. It is unclear whether the man was an observer or target of federal operations. ICE did not respond to Sahan’s request for comment on the operations.

At multiple points during the operation, agents deployed chemical agents at observers. Agents fired pepper balls at observers’ feet and threw canisters of tear gas at the corner of 34th Street and both Park and Oakland avenues prior to leaving the scene. Eyewitness Moses Wolf said there was no singular precipitating event that led to tear gas being deployed on Park Avenue.

“There was a crowd confronting each other telling ICE to get out,” Wolf said. “I didn’t really see any physical altercation happening.” He said it appeared to be a tactic by ICE agents to exit the scene.

Wolf said the confrontation prior to the deployment of tear gas had not escalated beyond what had already been happening.

“It wasn’t anything crazy,” Wolf said. “I turned around for one second and there was this whole entire cloud of it, and pepper spray came with that.”

Eyewitness Neph Sudduth said at Oakland Avenue agents used tear gas as they were leaving.

“They were finally leaving, it was the last car of the convoy,” Sudduth said. “They just threw two or three canisters out at us as they left.”

Both Sudduth and Wolf said they witnessed agents using pepper spray out of the windows of their vehicles as they drove off.

“They just wanted to hurt us cause we told them how we felt, and they didn’t like it,” Sudduth said.

The operation in Powderhorn is part of a flood of federal immigration activity in Minnesota. As many as 2,000 federal agents are present in the state according to reporting from the New York Times, with an additional 1,000 set to be deployed.

For Gomez, the clash with ICE is the new reality of life in the Twin Cities with federal agents present.

“This is what our streets are like,” Gomez said. “We have these masked, unaccountable unknown to us federal agents, and it’s like they’re the secret police.”

Despite the difficulties, Gomez believes observers should and will continue to show up to meet federal agents in the streets.

“Our community is undeterred,” she said. “We’re not going to just lay down. You can gas us and mace us all you want, we’re not going to just lay down.”

Sahan Journal reporter Andrew Hazzard contributed to this story.

1. Numbers

During the 2024 campaign, Donald Trump promised to deport every illegal immigrant who was a rapist, murderer, or thief. He also promised to deport 20 million immigrants. Some voters believed the first promise; other voters believed the second.

Because people are stupid, that first group of voters believed that there were 20 million undocumented immigrants who have committed felonies. This is not possible. The total number of people in jail in America today—this includes federal, state, local, and tribal land prisons—is just under 2 million. The number of undocumented immigrants who have committed serious crimes cannot be 10x the entire prison population of the United States. If it were, then daily life in America would look like Escape from New York.

So some Trump voters were duped owing to their general ignorance and/or innumeracy.

But others were not. Others signed up for Trump because of his second promise (the 20 million deportations) and viewed the first promise (about deporting only criminals) as the pap necessary to get the suckers onboard.

There are two crucial questions about these two groups. The first is:

What is their relative size? What percentage of Republican voters were tricked into voting for Trump’s immigration policies versus what percentage are getting exactly what they wanted?

Would you like to guess? Go ahead. I promise that whatever you’re thinking, it isn’t dark enough.

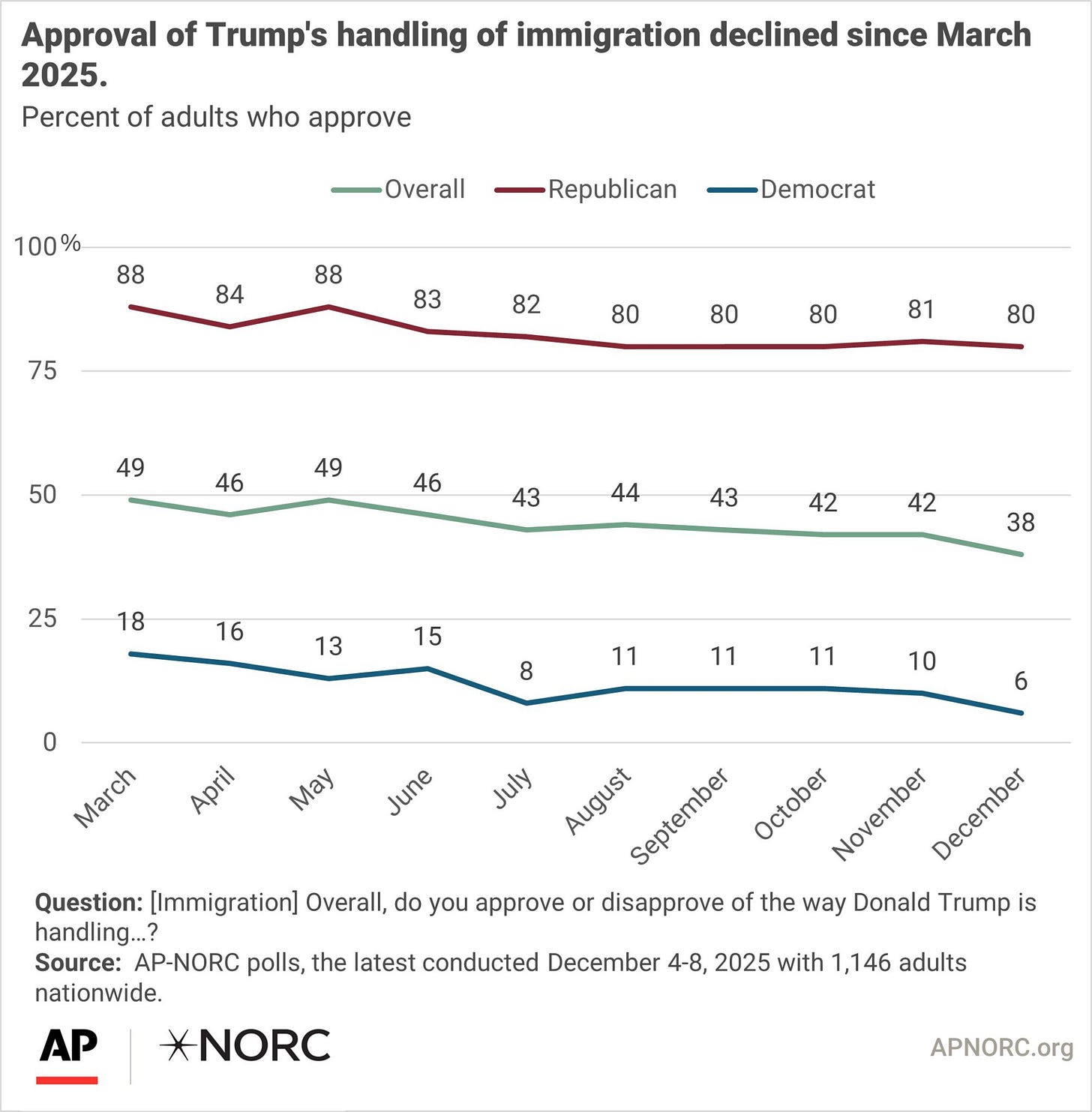

Here’s a survey tracking Republican approval of Trump’s immigration policies (the top line, in red) over most of 2025:

That’s a consistent level of support around 80 percent. Now here is the first poll conducted after the killing of Renee Good:

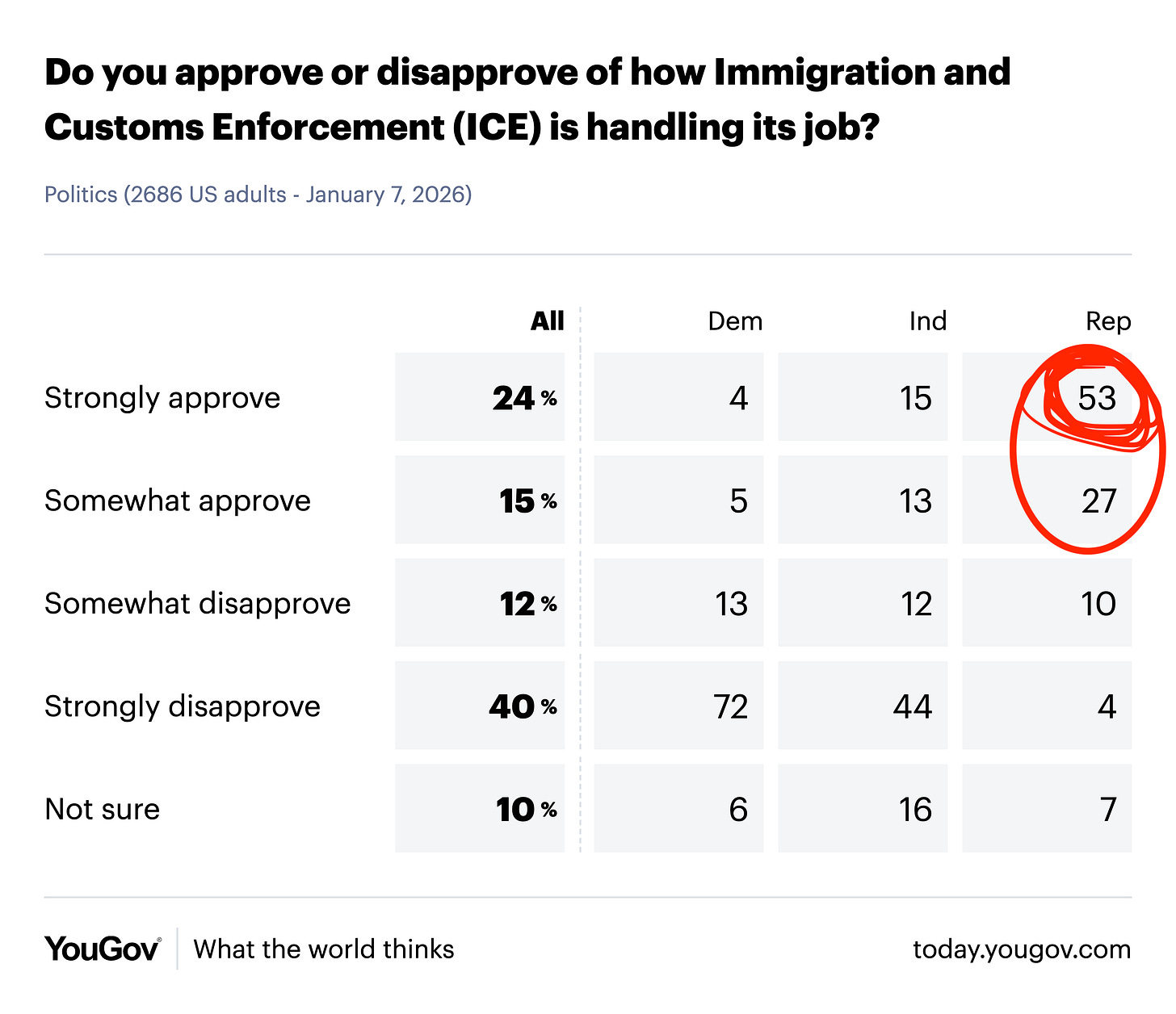

Even after the killing of an unarmed American citizen, a total of 80 percent of Republicans approve of what ICE is doing and 53 percent of Republicans strongly approve.

It seems pretty clear that, at best, one in five Trump voters were duped. The majority of them are getting exactly what they wanted.

Now if Trump were to lose the support of 20 percent of Republicans voters—or even 14 percent—it would be meaningful for Republican electoral prospects. Which is nice.

The problem is that having 80 percent of Republican voters actively supporting a fascist race war is meaningful for our societal prospects.

Which brings us to the second question: How are these groups distributed through the elite positions of power in government? And here it seems that many of the Republicans most invested in a race war have a great deal of power. Like, for instance, Vice President JD Vance, Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller, and Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem.

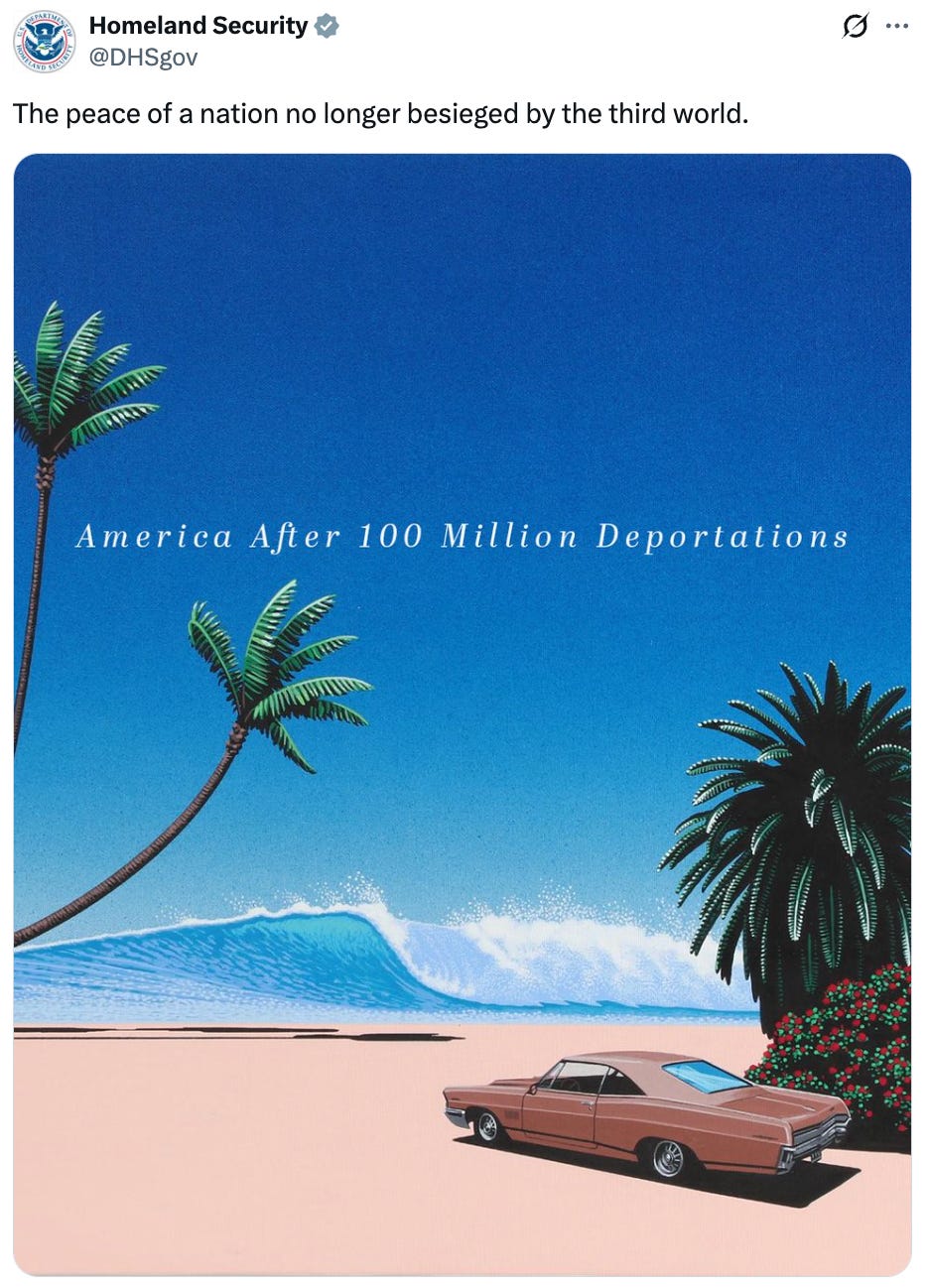

At the elite levels, even the idea of 20 million deportations is too little. Here’s a tweet from the Department of Homeland Security on New Year’s Eve:

100 million deportations?

There are 43 million foreign-born Americans. Most of them are legal immigrants. In order to perform 100 million deportations, DHS would have to round up every immigrant of any status—even naturalized citizens—and then also snatch 57 million American who are citizens by birth and deport them, too.

Want to guess who those other 57 million Americans might be?

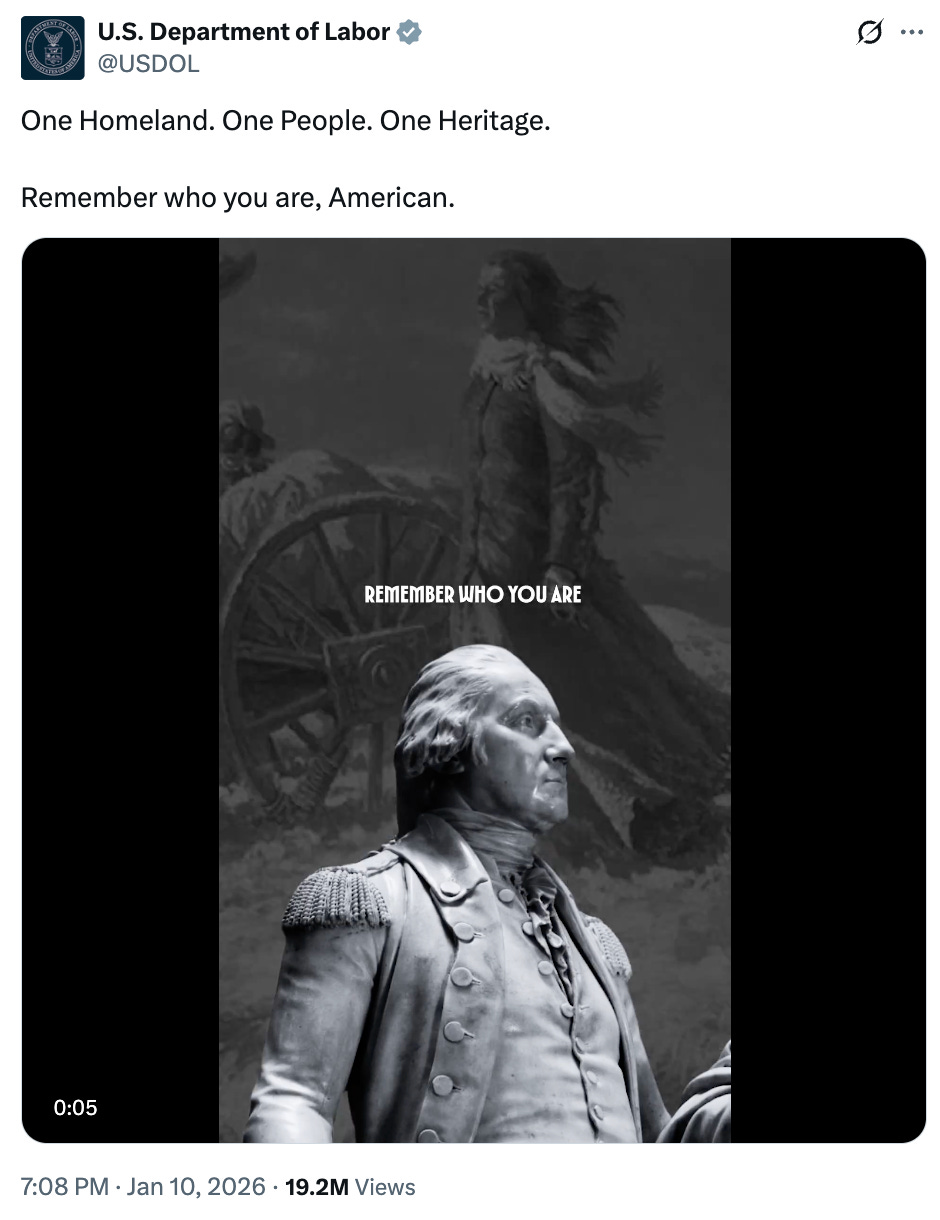

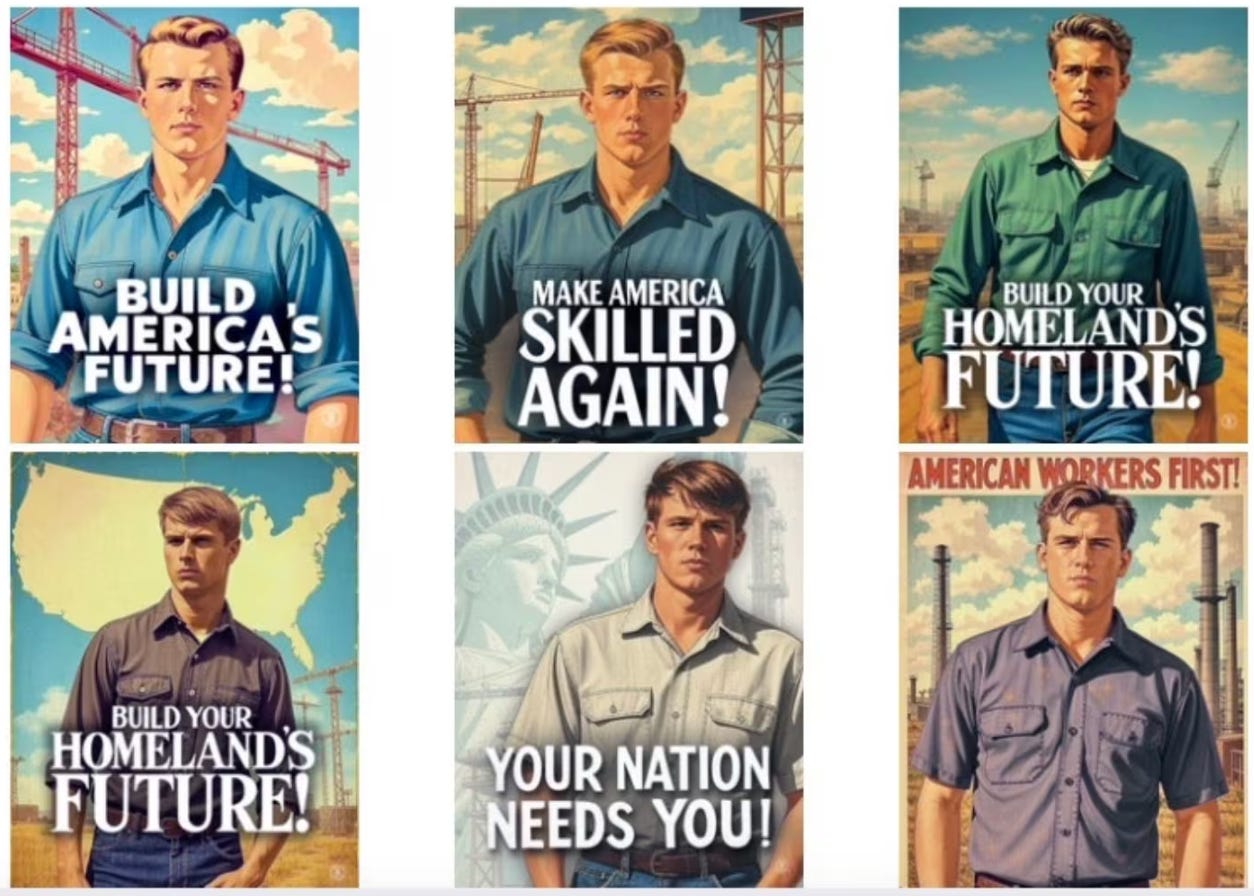

This week the Department of Labor published this:

Of course, the slogan sounds better in the original German.

Oh, and don’t forget the Department of Labor’s heroic propaganda posters depicting the American worker in a very specific way.

On the one hand, it feels weird to say that the U.S. government is attempting some low-key ethnic cleansing.

On the other hand, the reality is that we have a masked secret police force going door-to-door attempting to kidnap brown people; one government agency publicly daydreaming about deporting 100 million people; and another government agency saying that the ideal worker is a 20-year-old white guy.

2. Demographics

Another tell: This administration is obsessed with America’s falling fertility rate. From the NYT:

Vice President JD Vance last week called falling marriage rates “a big problem.” The deputy secretary of Health and Human Services in December urged his agency to “make America fertile again.” And at a recent conference for young conservatives, Sean Duffy, the transportation secretary, doubled down on the importance of marriage and children, holding out his nine kids as a model for others to follow.

Full disclosure: I am also obsessed with America’s falling fertility rate. Enough that I wrote a book about it.

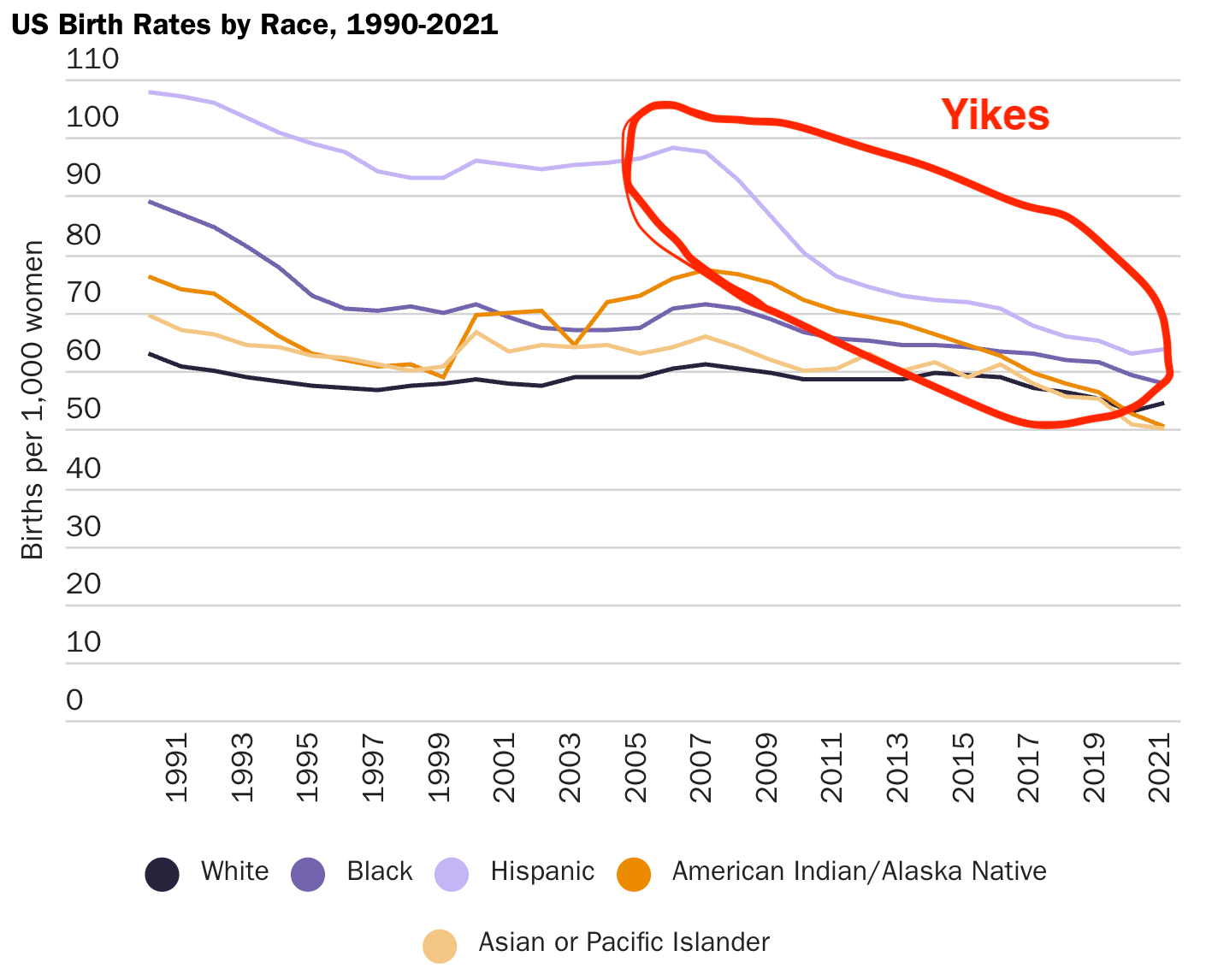

The problem here is that nearly all of the declines in total fertility rate (TFR) over the last decade have been the result of declining Hispanic fertility.

Here’s the deal: The TFR—the total number of kids the average woman has over the course of her life—has been below the replacement level, but relatively stable, among white and black Americans for the last generation or so. But America’s TFR kept declining anyway. Why?

Because Hispanic Americans—many of whom were recent immigrants—had TFR’s higher than the U.S. average. And their baby-making propped up the nationwide number. The problem is that, as recent immigrants spent time in America, their reproductive behavior began regressing to the mean. The shift has been dramatic:

If you were concerned about the fertility rate in America, would you be trying to (a) halt all immigration—since immigrants usually bring with them fertility rates higher than native-born Americans—and (b) deport 100 million people from the ethnic group that has the highest fertility rate?

No.

The only reasonable conclusion is that the concern of people in the Trump administration isn’t about the total fertility rate. It’s about the white fertility rate.

I don’t know how much clearer the regime could be.

So tell me: What does the pie chart look like on Republican voters and race war? What is the percentage of Trump voters in each of these categories:

- Group A: Sees and understands the administration’s intent and supports it.

- Group B: Sees and understands, but oppose it.

- Group C: Do not understand that the regime views its program as part of a race war and thinks it’s all business as usual?

And follow-up question: How big can Group A be for us to retain a functional, liberal society?

I look forward to your discussion.

Source: Jonathan V. Last, “The Nazi Slogans Are Not an Accident,” The Bulwark, 13 January 2026. I subscribe to the Bulwark, and so I have shared this article here as a service to my own readers. ||||| TRR

[. . .]

“Mr. Speaker, I rise today to announce I will be impeaching Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem,” announced Rep. Robin Kelly of Illinois.

“Secretary Noem has violated the Constitution and she needs to be held accountable for terrorizing our communities. Operation Midway Blitz has torn apart the Chicagoland area. President Trump declared war on Chicago and then he brought violence and destruction to our city and our suburbs in the form of immigration enforcement.”

Rep. Kelly then broke down some of the outrageous violence that ICE has visited upon her district.

“In my district, federal agents repelled down from Black Hawk helicopters and burst into an apartment building in the South Shore area. They dragged US citizens and non-citizens alike out of their beds in the middle of the night. They claimed the apartment was infiltrated by members of a Venezuelan gang. I don’t understand this president’s obsession with Venezuela, but they did not arrest a single member from that gang.”

“I visited that apartment building and saw firsthand the destruction those agents left. Doors to people’s homes or apartments were kicked down. Belongings, including little kids’ toys, were strewn about in the hallway. That raid and so many others shook our community, not just immigrants, but everyone. Now, Secretary Noem has brought her reign of terror to Minneapolis after she left Charlotte and Raleigh. We have all seen what happened.”

“ICE officers shot and killed Renee Nicole Good in cold blood. Without knowing any of the facts or an investigation, Secretary Noem lied about what happened. She called [a] beloved 37-year-old mom a domestic terrorist. Secretary Noem and her rogue agents are the ones terrorizing our communities, and she is breaking the law to do so. I will hold her accountable.”

“I’m filing three articles of impeachment against Secretary Noem. Number one, obstruction of Congress. Secretary Noem has denied me and other members of Congress oversight of ICE detention facilities. It is our constitutional duty to find out what’s happening in these centers where people are reportedly being treated like less than animals. Two, violation of public trust.”

“Secretary Noem directed ICE agents to arrest people without warrants, use tear gas against citizens, and ignore due process. She claims she’s taken murderers and rapists off our streets, but none of the 614 people arrested during Operation Midway Blitz has been charged or convicted of murder or rape.”

“Three, self-dealing. Secretary Noem has abused her power for personal benefit. She steered a federal contract to a new firm run by a friend, her friend. Her propaganda campaign to recruit ICE agents cost taxpayers $200 million. She made a video that turned the South Shore raid into something that looked more like a movie trailer. But make no mistake, this is not a movie. This is real life and real people are being hurt and killed. I really have to wonder who are the people behind the mask. These DHS agents have no identifying factor.”

“From all their botched raids and officer-involved shootings, I have to ask, what is their training like? What is the vetting? Is Secretary Noem recruiting January 6th insurrectionists? I was one of the last members of Congress to escape the House Gallery on January 6th. I remember hiding on my hands and knees and running through the hallways to a safe room. Insurrectionists are not fit to serve as law enforcement. I realize that impeachment of Secretary Noem does not bring Renee back.”

“True justice would be Renee alive today at home with her family. Impeachment doesn’t bring back the four other people killed by immigration officers this year, including a man in Chicago. We could not bring them back to their loved ones. What we can do, though, is impeach Secretary Noem. Hold her accountable. Let her know the public is watching. In this country, we do not kill people in cold blood without consequences. These are not policy disagreements.”

“These are violations of her oath of office and she must answer for her impeachable actions.”

[. . .]

Source: Occupy Democrats (Facebook), 13 January 2026

Audience members at the all-ages Minneapolis rock venue Pilllar Forum tussled with ICE agents on the street outside the club on Sunday — prompting that night’s show to be canceled.

The owner of Pilllar Forum, Corey Bracken, said several of his customers and musicians were pepper-sprayed by ICE agents and at least two were hit with batons on the street outside the venue, at 2300 Central Av. NE., where other ICE detainments and community protests have happened in recent days.

“My staff doesn’t feel safe after this, and our artists and customers don’t feel safe,” said Bracken, a dad who expanded his skateboarding store into a music venue and coffee shop in 2023 to bring more live music and art to underage fans.

He is leaving it up to his staff and the bands themselves to decide whether to proceed with upcoming concerts, including several more scheduled this week.

The ruckus started shortly after the 6:30 p.m. showtime for a four-band bill headlined by Pilllar Forum regular Anita Velveeta, a popular trans/queer punk act. Audience members saw ICE agents pull up and detain two individuals outside the neighboring Supermercado Latino market, prompting the club’s young music fans to quickly exit onto the street and protest the agents’ actions.

The Department of Homeland Security didn’t respond to a Star Tribune request for comment. An employee at Supermercado Latino also declined to comment on the incident.

Antonio Carvale, singer/guitarist in one of Sunday’s opening bands, BlueDriver, said he was one of five people at the venue who had to be treated with water and saline solution after being hit with pepper spray. He said agents fired the spray after they pushed a protester who pushed back.

“Honestly, the pain felt brutal, but fortunately the community was prepared and helped treat our eyes,” Carvale said, but he commiserated with a bandmate who was also struck by a baton and “banged up pretty bad.”

The band was disappointed Sunday’s gig then was canceled, but he added, “It would’ve been hard to play when I couldn’t even see the frets.”

One of the audience members who was pepper-sprayed, Jess Roberts of Minneapolis, said she had to go to an urgent care clinic because she was sprayed in the ear, which led to an infection.

The run-in with ICE followed a viral Instagram post by Pilllar Forum that went up Friday and landed 25,000 likes. It showed a peaceful but loud crowd of protesters shouting down ICE agents on Central Avenue, with the message, “And that is how you get it done.”

Minneapolis City Council President Elliott Payne and the new Minnesota state senator representing northeast Minneapolis, Doron Clark, joined Bracken in another social media video posted late Sunday denouncing the incident. Clark called Pilllar Forum “an institution here on Central.”

Payne urged residents, “Stay safe and stay vigilant.”

Twin Cities musicians and music fans offered online support for Pilllar Forum after Sunday’s mayhem.

“Thank you for supporting the community!” veteran rocker Tim Ritter of the band Muun Bato wrote on the venue’s Facebook page.

Bracken did offer refunds to paid attendees of Sunday’s canceled show, proceeds of which were to be donated to families affected by ICE detainments, per headliner Anita Velveeta’s request.

“So far, I haven’t heard from anyone who wants their money back,” Bracken said.

Source: Chris Riemenschneider, “Music fans scuffle with ICE outside all-ages Minneapolis rock venue,” Minnesota Star Tribune, 12 January 2026. I subscribe to the online edition of this newspaper (which I grew up reading as a kid), and so I am just as happy to share its contents here when appropriate. ||||| TRR