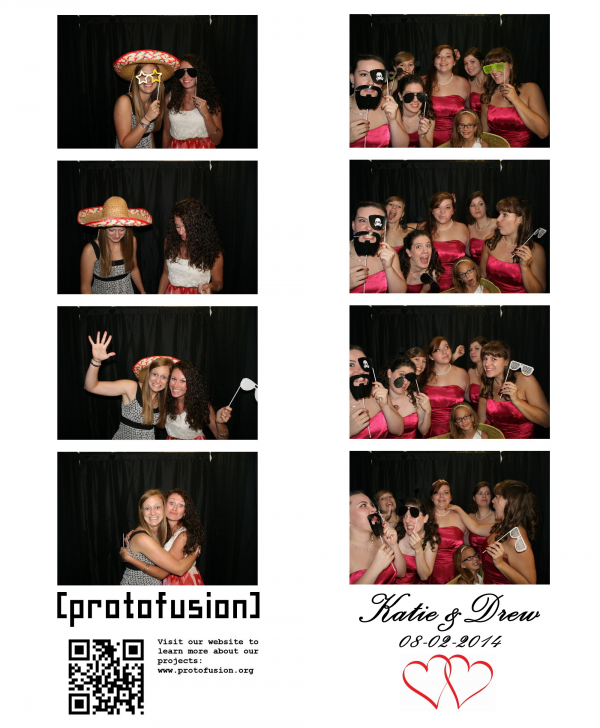

Sample photobooth photostrips

Photobooths are popular at many types of social events, including weddings, birthday parties, and school dances. However, renting one can easily cost upwards of $1000, making them impractical for many events. So when a friend mentioned wanting one for her wedding, I jumped at the opportunity to build a low-cost DIY photobooth.

To make my photobooth cost-efficient, I decided to use a thermal receipt printer to print out black and white photo strips, which eliminates the need for an expensive photo printer and photo paper/ink. I also added Twitter integration so the photobooth can tweet out every photo strip it takes, and a QR code generator that prints a link to the corresponding Twitter post on each photo strip.

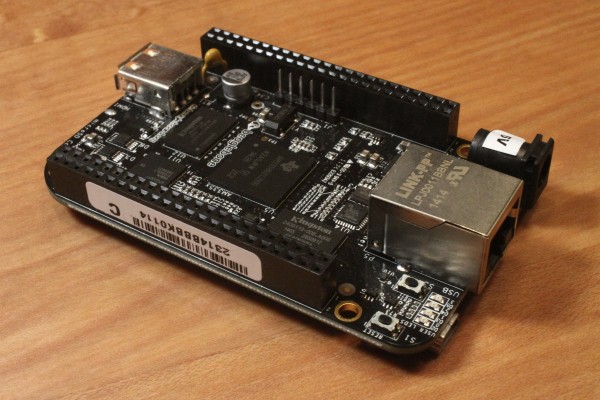

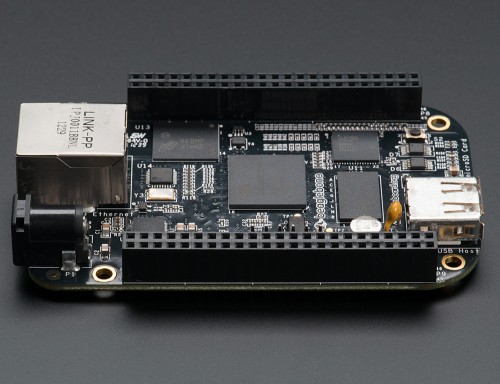

The BeagleBone Black single-board computer seemed like a perfect match to power this project, and I decided to script everything in Python to keep it simple. Gphoto2 provides the camera interface, CUPS handles the printing, and Python libraries take care of everything else.

Lets get into the details of how this thing works.

Electronics

The BeagleBone Black will boot up into a usable state without any setup required. However, I found that some gPhoto2 functions did not work with the Debian install that came preloaded on my BBB. To solve this issue, I switched to Arch Linux ARM. Instructions on installing Arch on the BeagleBone can be found here.

The basic features I wanted the photobooth to have are user input to start a photo sequence, camera control to take pictures, Twitter communication to tweet photos, and support for printing the final product. Thankfully each of these features is relatively easy to implement with Python.

I used Python 3 to allow support for some newer Python libraries. Unfortunately, this eliminated the possibility of using Adafruit’s Python GPIO library, which is only compatible with Python 2. Instead, I used the manual approach of exporting the GPIO pins to files in the /sys/class/gpio/ directory and reading the pin status values from the files. In Python, it looks a little something like this:

import io

# export pin 7

f = open('/sys/class/gpio/export', 'w')

f.write('7')

f.close()

# define pin 7 direction as input

f = open('/sys/class/gpio/gpio7/direction', 'w')

f.write('in')

f.close()

# read pin 7 status

f = open('/sys/class/gpio/gpio7/value', 'r')

status = f.read()

if("1" in status):

# do something

elif("0" in status):

# do something else

f.close()

# unexport pin 7

f = open('/sys/class/gpio/unexport', 'w')

f.write('7')

f.close()

The GPIO pins can be used to capture button presses and trigger the photo sequence.

The primary function of a photobooth is to take pictures, so if nothing else we’re going to have a camera in the setup. The Gphoto2 library takes care of camera integration and simplifies it down to just a few commands. The library supports thousands of camera models, so chances are your camera will work. A list of supported cameras can be found here. Since I wanted to take 4 pictures in a row with even spacing and immediately download the pictures, I used the following command and arguments:

gphoto2 --capture-image-and-download --interval=3 --frames=4 --filename /tmp/portrait%n.jpg --force-overwrite

The arguments can be modified to fit various needs—for example, saving the photos on the camera’s internal memory after they have been downloaded.

I wanted to display live view from the camera on a monitor that would allow users to see themselves as they pose for pictures, but I wasn’t able to get this working. Gphoto2 seems to turn off live view on my camera after the first picture is taken, and it won’t come back on until the camera is power-cycled. I will be working to find a solution for this issue in the future, possibly by streaming the live view video to the BBB and displaying it from there, or by replacing the camera with a high-def web cam, but until then I will live without it.

To give the user feedback when each picture is taken (in the absence of live view), I decided to turn on the camera flash, even though using the built in flash is less than optimal. Without this feedback, it is difficult to tell when each picture is being taken and when the set is finished. To minimize the blinding effect a bright flash tends to have, I turned down the flash brightness to around a 16th of its usual strength.

Because a photobooth tends to be fairly dark, and since I wasn’t relying on the flash for full lighting, I added some extra lighting to the setup. I decided to use Protofusion’s Luma lighting system to give me flexible control over the lighting through the BeagleBone Black. This allowed me to easily set the lighting levels and give some additional feedback regarding program state or errors by flashing the lights different colors. Using the Luma LED Strip Driver and an LED strip, I was able to string lighting around the top of the booth and light it with a soft, distributed light. In the absence of such a high tech lighting system, any standard light source could be used. If the light source tends to be direct and harsh, I would recommend some type of diffuser to distribute and soften it out a bit.

I picked the Dymo 400 Labelwriter to print the photo strips because I could find it on eBay for pretty cheap, and it seemed widely used and supported. To use it with the BBB, I installed the CUPS printing system and found the Dymo driver in the Arch User Repository (I recommend Packer for installing packages from the AUR). Here is a good tutorial on installing and configuring CUPS.

To make the Dymo 400 print the way I wanted, I had to make a few tweaks. When I chose the “Continuous Feed” paper option in CUPS, it would print a large margin at the top of strip, so I tried setting a custom paper size. No matter what custom paper size I set, the printer would always print out the strip, and then print out an equal amount of blank paper. There may be a solution to this, but I was unable to find it. So the work around I used was to manually change the default printing settings for the printer, by going through the printer configuration file and changing the printable area for the “Continuous Feed” paper option. The modified file can be found below.

To format the individual photos into one photo strip, along with some text and a QR code at the bottom, I chose the ImageMagick command line image editing tool. I used the convert -append command to assemble all the photos into one image. The one problem I found here was that the large photos taken by the camera were too large for the program to combine into one with the limited RAM on the BeagleBone. Instead, I resized each of the photos and then assembled the smaller images. Since the Dymo 400 printer has a printable width of 672 pixels, I converted all the images down to that size. Here is the sequence of commands I used to assemble a photo strip:

# resize each of the pictures and add a border to make them go together nicely

convert /tmp/portrait1.jpg -sample 26% -bordercolor '#FFFFFF' -border 2x20 /tmp/portrait1.jpg

convert /tmp/portrait2.jpg -sample 26% -bordercolor '#FFFFFF' -border 2x20 /tmp/portrait2.jpg

convert /tmp/portrait3.jpg -sample 26% -bordercolor '#FFFFFF' -border 2x20 /tmp/portrait3.jpg

convert /tmp/portrait4.jpg -sample 26% -bordercolor '#FFFFFF' -border 2x20 /tmp/portrait4.jpg

# put the pictures all together and add the protofusion logo

# this is the version I tweeted

convert -append /tmp/portrait1.jpg /tmp/portrait2.jpg /tmp/portrait3.jpg /tmp/portrait4.jpg /root/protofusion.jpg /tmp/twitter.jpg

# resize the QR code

convert /tmp/qrcode.jpg -sample x245 /tmp/qrcode.jpg

# add the QR code and some text together horizontally

convert +append /tmp/qrcode.jpg /root/photoboothtext.jpg /tmp/qrblock.jpg

# add the QR code and text to the photo strip

# this is the version I printed

convert -append /tmp/twitter.jpg /tmp/qrblock.jpg /tmp/print.jpg

In order to Tweet photos, the photobooth needs to be connected to the internet. I used a TP-LINK TL-WN722N wifi dongle I had laying around, but any of the adapters on this list as well as many others should work well. The Arch Wiki details the steps for connecting to a wifi network in Arch Linux.

Twitter integration adds a fun twist to the traditional photobooth. I used the twython Python Twitter API wrapper, which simplified many of the steps. The only tricky part is authenticating through Twitter’s three step authentication process. I haven’t yet added authentication support to my script, so I just manually hard-coded in the generated keys needed. I hope to add Twitter authentication to the next iteration, and will write about that when I finish it.

To give users an easy way to find their tweeted photos, I used a Python QR code generator called qrcode that generates a QR code with a link to the posted image. The generator takes the link returned by the Twitter API and spits out a QR code which is saved and appended to the photo strip. I also added some custom text next to the QR code to explain what the QR code links to.

You can find my Python code here: photobooth.zip

You can find the cups printer config file I used here: printer_config.zip

Here is a list of the tasks (detailed above) that need to be completed to set up the full system:

- Install Arch Linux

- Install Packer

- Install Python

- Install Python libraries:

- twython

- oauthlib

- qrcode

- pyserial

- Install and configure Cups

- Install and configure printer drivers

- Setup wifi connection

- Install Gphoto2

- Install ImageMagick

Physical

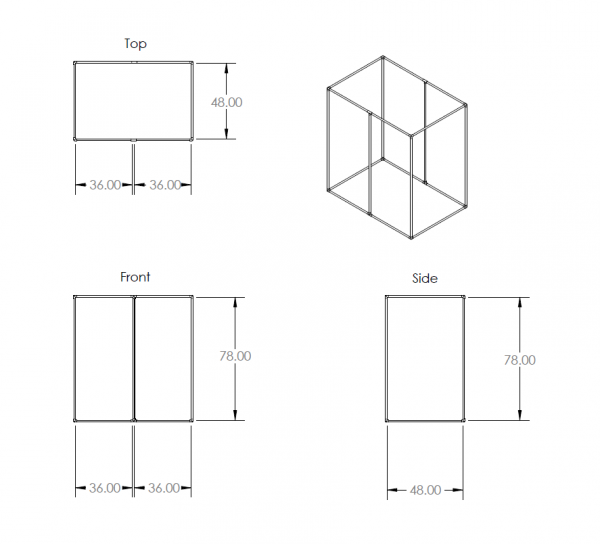

The physical aspect of the photobooth was the easiest part to build, although my simple design has the potential to be greatly improved. To create the enclosure, I opted for a simple PVC pipe frame that could be quickly disassembled and easily transported. I made the enclosure 6 feet long, 4 feet wide, and 6.5 feet tall. These dimensions can be adjusted based on application, but I wanted plenty of space in mine for several people to stand and pose. So far, up to seven people at a time have successfully fit in it. The length really depends on the type of camera and focal length being used, but 6 feet seems like a good starting place. The height is also highly variable, especially if people will be sitting. But since I designed with standing in mind, I wanted to accommodate some of the taller potential users.

I chose ¾” PVC as a good compromise between cost and strength, and was able to find the elbow pieces I needed to assemble a cube. Here is the design I used for the frame:

Once the frame was built, I chose curtains to cover it. Curtains are a slightly more expensive choice than some of the other options (bedsheets, etc.), but they come pre-made in various lengths, with loops in the top that make them perfect for hanging on PVC. I chose black to create a more private feel in the booth, but in hindsight, something lighter may have allowed better contrast in the photographs and prints.

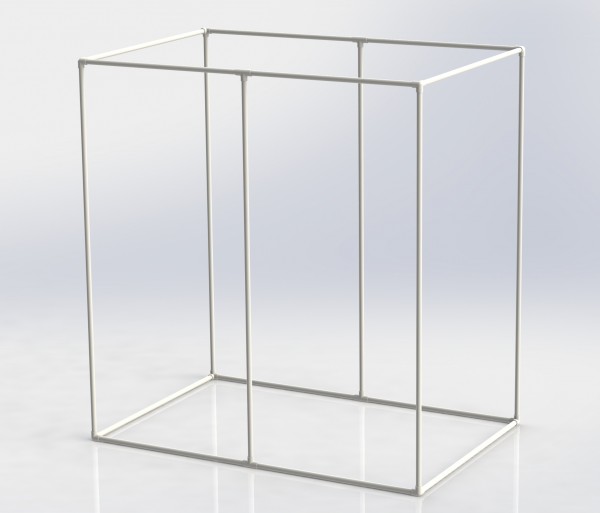

When I was looking to find some sort of button to use to trigger the photo sequence, I came across a round foot pedal from a tattoo machine. This worked especially well because the booth is designed to be used standing up. However, any type of input could be used to trigger the sequence.

The photobooth setup also needs a tripod, or something to hold the camera. I used this tripod and was really happy with it. Lighting is also important in a photobooth, so some sort of fill lighting would be desirable. As mentioned above, I found a fancy solution to this, but any light source should work. I also found that some people tend to be confused no matter how straightforward the interface is. Although it may seem tacky, an instruction sheet can really clear up confusion, and when creatively designed, can blend in seamlessly with the look of the booth.

A photobooth can help create spontaneous and memorable moments at any party or get-together. I hope the details here will inspire someone to build their own, because sometimes it’s more fun to do it yourself!

Materials

Here’s a list of the materials I used to make the photobooth, along with an idea of what they all cost.

- Beaglebone Black x 1 = $65

- USB hub x 1 = $15

- Wifi adapter x 1 = $18

- Thermal printer x 1 = $30

- Receipt paper x 4 = $24

- Foot pedal x 1 = $12

- Tripod x 1 = $20

- PVC pipes x 10 = $25

- PVC connectors x 12 = $12

- Curtains x 6 = $60

Total = $281

Already had:

- Camera

- Lighting

Tools:

- Hack saw

- Screw drivers

- Wire cutters

- Computer

The BeagleBone Black is an ARM-based device and doesn’t have ACPI support like most x86 systems. ACPI generally handles triggering shutdown and other power management events on x86 systems, so this functionality is missing on the BeagleBone. We can easily work around this problem with acpid, which provides an event handling script that is triggered when the power button is pressed. This is a simple way to add power button triggered shutdown without actually having ACPI support in the hardware.

First, install acpid from your distribution’s package manager. For Arch Linux ARM:

sudo pacman -S acpid

Next, open /etc/acpi/handler.sh in a text editor. Look for the snippet containing “PowerButton pressed” near the beginning of the script. After this line, add a new line with “poweroff” on it. You may also add any other commands you wish to run when the power button is pressed.

case "$2" in

PBTN|PWRF)

logger 'PowerButton pressed'

poweroff

;;

*)

logger "ACPI action undefined: $2"

;;

esac

;;

Now enable and start the acpid daemon. On systemd-based distros, use the method below.

systemctl enable acpid.service systemctl start acpid.service

Now that acpid is running, power button events will be handled by the events script. Note that the acpid service will generate errors in its log because it is unable to communicate with the kernel, but the poweroff will execute as expected.

Finally, press the power button on your BeagleBone and it should begin shutting down. If you encounter any issues, check the logs of the acpid service to make sure it launched properly. Also double-check your syntax in the event handler script.

]]>

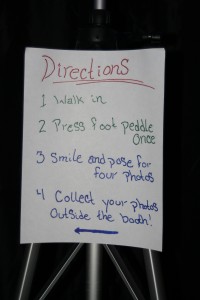

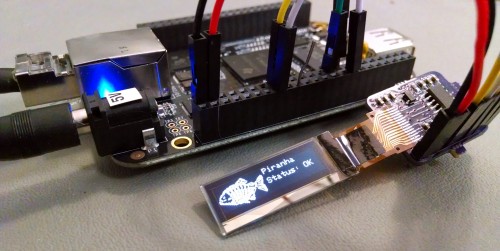

The SSD1306 is an OLED display made with SPI and I2C interfaces. With a simple Python library I adapted (a modified version of py-gaugette), it is easy to render text, images (from bitmaps of pretty much any format), progress bars, etc. This guide is a bit on the long side, but should walk you through the whole process.

Unloading the capes

To use the SPI port, you first need to unload the HDMI virtual capes. Just echo a dash and the number of the virtual cape you want to remove to the slots file, as shown below:

# cat /sys/devices/bone_capemgr.9/slots 0: 54:PF--- 1: 55:PF--- 2: 56:PF--- 3: 57:PF--- 4: ff:P-O-L Bone-LT-eMMC-2G,00A0,Texas Instrument,BB-BONE-EMMC-2G 5: ff:P-O-- Bone-Black-HDMI,00A0,Texas Instrument,BB-BONELT-HDMI 6: ff:P-O-- Bone-Black-HDMIN,00A0,Texas Instrument,BB-BONELT-HDMIN 7: ff:P-O-L Override Board Name,00A0,Override Manuf,BB-UART5 8: ff:P-O-L Override Board Name,00A0,Override Manuf,BB-UART2 # echo -5> /sys/devices/bone_capemgr.9/slots # echo -6> /sys/devices/bone_capemgr.9/slots # cat /sys/devices/bone_capemgr.9/slots 0: 54:PF--- 1: 55:PF--- 2: 56:PF--- 3: 57:PF--- 4: ff:P-O-L Bone-LT-eMMC-2G,00A0,Texas Instrument,BB-BONE-EMMC-2G 7: ff:P-O-L Override Board Name,00A0,Override Manuf,BB-UART5 8: ff:P-O-L Override Board Name,00A0,Override Manuf,BB-UART2

Load SPI overlay

Download spimux.dts and generate a dto file to load into the kernel overlay:

- Generate the code

dtc -O dtb -o BB-SPI1-01-00A0.dtbo -b 0 -@ spimux.dts

- Copy to firmware dir

cp BB-SPI1-01-00A0.dtbo /lib/firmware

- Load on demand

echo BB-SPI1-01 > /sys/devices/bone_capemgr.*/slots

Check results

You should now see the SPI cape loaded in the slots file and device nodes should be present at /dev/spidev*

# cat /sys/devices/bone_capemgr.9/slots 0: 54:PF--- 1: 55:PF--- 2: 56:PF--- 3: 57:PF--- 4: ff:P-O-L Bone-LT-eMMC-2G,00A0,Texas Instrument,BB-BONE-EMMC-2G 7: ff:P-O-L Override Board Name,00A0,Override Manuf,BB-UART5 8: ff:P-O-L Override Board Name,00A0,Override Manuf,BB-UART2 9: ff:P-O-L Override Board Name,00A0,Override Manuf,BB-SPI1-01

If you don’t see anything here, check the output of dmesg for any errors.

Wire stuff up

You can connect a SSD1306 to the BeagleBone Black with one of Adafruit’s breakout board, or with your own PCB design (you can use the footprint from Adafruit’s open-hardware design files).

- P9_1 – GND

- P9_3 – Vcc

- P9_13 – Data/CMD

- P9_15 – Reset

- P9_17 – Chip select

- P9_18 – Master out / slave in

- P9_22 – Clock

Install Python Libraries

You’ll need a few supporting libraries to make everything work:

- py-spidev

- adafruit-beaglebone-io-python

- python2-ssd1306-bb (the actual OLED display library)

If you’re running Arch Linux, just install python2-ssd-bb from the AUR with your favorite AUR helper like packer, and all dependencies will be pulled in automatically.

packer -S python2-ssd1306-bb

On an Angstrom-based system, you can use opkg to install the dependencies:

opkg update opkg install python-pip python-setuptools python-smbus pip install Adafruit_BBIO pip install spidev

Run the Test Script

In the python2-ssd1306-bb/samples folder, run ssd1306.py. This file will show some test patterns on the screen. If you installed from the AUR and don’t have the test script, you can download it here.

If you do not see the test patterns on your display, double-check all of your connections (make sure you don’t mix up power and ground!). Otherwise, you can move on to using the library from your own code!

Using the Library

Want a progress bar?

Just call the draw_progress function with position, width, height, and the desired percent. Call the function again with a different percent value. to update the progress bar. Percent values are numbers 0-100. This function isn’t very well-tested yet, please comment if you encounter problems!

draw_progress(self, percent, x, y, width=128, height=5): led.display()

Want to render an image?

Make sure you scale your image and convert to black/white first! All standard image formats are supported.

led.clear_display()

led.draw_image("/home/jsmith/logo.png", x, y)

Want to render some text?

led.draw_text2(x, y, 'Hello World', size)

Refer to the readme on BitBucket for an up-to-date overview of the library, or take a look at the test script code. If all goes well, you should be able to get results like this:

The person who wrote py-gaugette also ported his library to BeagleBone Black, although it uses a different approach for SPI communication and doesn’t have progress bars / image rendering (yet!).

]]>

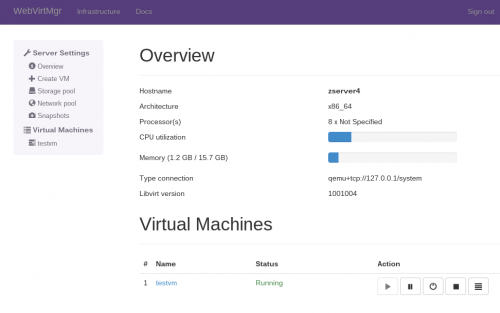

WebVirtMgr is an awesome simple web interface for managing virtual machines on Linux. Unfortunately the installation process is not simple at all, and the documentation is a bit lacking. There are also a few issues which are documented only in the bugtracker and not the documentation, as well as some Arch-specific issues. I’ve compiled all of the fixes I’ve discovered below, so hopefully your install process won’t be as painful as mine.

Updated 2/19/14 to reflect bugfixes and updates

Updated 3/11/14 for code and package updates

Prereqs

First, make sure you have novnc installed, which is currently available from the AUR. Install it manually or use your favorite AUR helper.

packer -S novnc gunicorn

The backend of this web interface runs on libvirtd, which must be installed, along with some optional dependencies:

pacman -S libvirt urlgrabber qemu dnsmasq bridge-utils ebtables dmidecode python2-django

Next, edit the configuration file /etc/conf.d/libvirt and add –listen to the args:

LIBVIRTD_ARGS="-p /var/run/libvirt.pid --listen"

Now edit /etc/libvirt/libvirtd.conf. Disable tls, enable tcp, set auth to sasl. Everything else should be commented out for simple configurations.

auth_tcp = "sasl" listen_tls = 0 listen_tcp = 1

Edit /etc/libvirt/qemu.conf and make sure that vnc_listen is set to listen on all addresses.

vnc_listen = 0.0.0.0

You may want to enable additional VNC options which may solve VNC encryption problems I discuss below. Let me know if this works for you!

Now start the libvirtd service:

systemctl enable libvirtd systemctl start libvirtd

Installation

Clone the git repository to /var/www/webvirtmgr and then change the owner to http

git clone git://github.com/retspen/webvirtmgr.git

chown -R http:http /var/www/webvirtmgr

Next, edit manage.py and change “python” in the first line to “python2”. Alternatively, use one of the other official methods of dealing with multiple versions of python on Arch Linux.

Run manage.py to generate the database and create credentials.

./manage.py syncdb

Apache Config

This section is incomplete, Apache now just needs to proxypass the gunicorn server from localhost:8000

Put configuration for proxypass here

Make sure you include this conf file in your main apache config by adding this line to /etc/httpd/conf/httpd.conf

Include conf/extra/webvirtmgr.conf

Finally, restart apache so your changes take effect

systemctl restart httpd.service

Gunicorn Server

WebVirtMgr is now served with gunicorn. The developer launches this service with supervisor to overcome limitations of initscript-based systems, but systemd fills this need nicely> I wrote a simple service file to handle webvirtmgr:

[Unit] Description=WebVirtMgr Gunicorn Server [Service] User=http Group=http ExecStart=/usr/bin/env python2 /srv/webvirtmgr/manage.py run_gunicorn -c /var/www/webvirtmgr/conf/gunicorn.conf.py Type=simple Restart=on-failure [Install] WantedBy=multi-user.target

Copy this file to /usr/lib/systemd/system/webvirtmgr.service and start the service!

systemctl enable webvirtmgr.service systemctl start webvirtmgr.service

Add Users

Adding users is currently done on the command line. Use this command to add the user “joe”:

saslpasswd2 -a libvirt joe

NoVNC Configuration

For easy remote control of your virtual machines, you probably want to use the novnc feature of WebVirtMgr.

First, edit /var/www/webvirtmgr/console/webvirtmgr-novnc and replace “python” on the first line with “python2” or use the alternative method(s) as mentioned above.

Copy the service from conf/initd/webvirtmgr-novnc-arch to /usr/lib/systemd/system/webvirtmgr-novnc.service (make sure to include the .service extension which is omitted in the repository).

Next, create a systemd service file in /etc/systemd/system/webvirtmgr-novnc.service

Now enable and start the service you just created.

systemctl enable webvirtmgr-novnc.service

systemctl start webvirtmgr-novnc.service

NoVNC Encryption Fix

This issue is now resolved, see the github issue for details.

NoVNC doesn’t work with SSL because encryption is automatically enabled, which fails for some reason. To disable encryption, edit templates/console.html and force set encrypt to false.

rfb = new RFB({'target': $D('noVNC_canvas'),

'encrypt': false,

'repeaterID': WebUtil.getQueryVar('repeaterID', ''),

Use the Interface

Navigate to the virtual host you configured and you should be greeted with a web interface! If you have any issues, feel free to leave a comment below.

Other Items

There were a few things I didn’t cover which are covered by WebVirtMgr’s actual documentation, such as configuring your firewall and verifying that libvirt is working properly. I strongly recommend you take a look at their documentation (especially the last two sections).

]]>

Arch Linux ARM currently includes an unpatched version of dtc (device tree compiler) which lacks the “@” option. If you want to enable additional UARTs, SPI, I2C, or just use GPIO without recompiling the bootloader, you need a patched version of dtc. You can download the source code and manually patch/compile, but to make this process easier I created a PKGBUILD which builds a patched version of dtc from git. Grab the raw PKGBUILD after the break, or just run packer to install from the AUR:

packer -S dtc-git-patched

Make sure you don’t have the vanilla version of dtc installed, pacman will throw “file exists on filesystem” errors if it’s already installed from the standard repository.

After installing dtc you can easily mux pins with the flattened device tree. For more information on muxing pins and enabling UARTs, check out the hipstercircuits guide.

# Maintainer: Ethan Zonca <[email protected]>

pkgname=dtc-git-patched

pkgver=20130410

pkgrel=1

pkgdesc="Device Tree Compiler with Dynamic Symbols and Fixup Support Patch"

url="http://jdl.com/software/"

arch=('i686' 'x86_64' 'armv7h')

license=('GPL2')

makedepends=('git')

_gitroot='http://jdl.com/software/dtc.git/'

_gitname='dtc.git'

build() {

msg 'Downloading dynamic symbols fixup patch...'

wget https://patchwork.kernel.org/patch/1934471/raw/ -O dynamic-symbols.patch

msg 'Connecting to GIT server...'

if [[ -d ${_gitname} ]]

then

cd ${_gitname}

git reset --hard HEAD

git pull -f

git clean -f

else

git clone ${_gitroot} ${_gitname}

fi

msg 'GIT checkout done or server timeout'

}

package() {

cd ${_gitname}

# Revert to version that patch applies to

git reset --hard f8cb5dd94903a5cfa1609695328b8f1d5557367f

# Apply patch

git apply ../dynamic-symbols.patch

# patch -Np1 -i ../dynamic-symbols.patch

make || return 1

make INSTALL=$(which install) DESTDIR=${pkgdir} PREFIX=/usr install || return 1

}

Image credit: Adafruit

Background

If you have a working BOPM installation, you are trying to prevent abuses of your IRC network effected through anonymity services such as proxies. BOPM has built-in support for scanning for open proxies. It also has support for looking up clients in DNSBLs, which are used to publish lists of misbehaving or malign hosts. One such DNSBL, called TorDNSEL, provides a way to check users connecting through the Tor anonymity service.

As discussed at TorDNSEL’s information page, the purpose of this service is to provide finely-grained information about whether a client’s connection could be through a Tor exit node. Tor exit nodes can be configured with advanced exit policies which specify the sorts of direct outbound connections a Tor exit node is willing to make on behalf of its anonymous client. For example, a Tor exit node administrator could disallow his node to make connections to government sites and disable outgoing connections on common IRC ports. If a Tor exit node is run by an administrator who is interested in also connecting to an IRC network, that administrator would disallow outgoing IRC connections. Thus, any IRC connection made (on a common IRC port) through that node would be a legitimate connection made by a user on that host and not a connection from an anonymous client. The TorDNSEL DNSBL lets—and requires—networks which use it to take this into account.

Prerequisites

This short guide assumes that you have successfully configured BOPM to connect to your IRCd, parse oper notices informing it of client connections, and issue a G/Z:line or SHUN for some other event which identifies a client as using a particular anonymity service.

Configuring BOPM

As TorDNSEL’s information page documents, performing a TorDNSEL lookup requires the IRC client’s IP A.B.C.D, the port of the service being accessed P, and the public IP of the IRCd E.F.G.H. With these parameters, a query would be an A record lookup of the domain name D.C.B.A.P.H.G.F.E.ip-port.exitlist.torproject.org. If the response was NXDOMAIN, then either there is no Tor exit node at A.B.C.D or, if that IP identifies an exit node, that node is unwilling to connect to E.F.G.H on port P because its exit policy forbids such a connection. If the response is 127.0.0.2, then there is a Tor exit node at A.B.C.D which would willying connect to E.F.G.H on port P. From this information, we can produce a BOPM blacklist block:

OPM {

# …

blacklist {

name = "P.H.G.F.E.ip-port.exitlist.torproject.org";

type = "A record reply";

reply {

2 = "Tor exit server";

};

ban_unknown = yes;

# GZLINE issuing a 7-day network-wide zline with UnrealIRCd-compatible syntax

kline = "GZLINE *@%i 7d :You are connecting from a Tor exit node willing to connect to E.F.G.H:P";

};

# …

};The above blacklist should be copy-pastable into your bopm.conf‘s OPM section. But, remember to replace E, F, G, and H with the respective components of your IRCd’s IP address. In the name line, it is intended that the components of the IP are in reverse order. This is because the right end of a domain is more general and the left end is more specific whereas in the first component of an IP address is most general and the rightmost component is more specific.

Also, note that you shouldn’t copy the … into your bopm.conf; each of these is just a placeholder indicating that you probably already have other blacklist blocks which should be preserved defined inside the OPM block.

One last note about this blacklist entry. If your IRC network, like many networks, allows connections to multiple ports, you must specify a blacklist entry for each port. For example, 6667 is the port an IRC client will try, by default, to use when connecting to an IRCd. But if a client wants to use SSL (without STARTTLS), you might have instructed your IRCd to listen for SSL connections on port 6697. A side effect of TorDNSEL’s specific entries is that a tor exit node may be instructed to deny outbound connections on port 6667 yet allow them on 6697. Since BOPM cannot (AFAIK) be configured to automatically choose a value for P, you must create a blacklist block for each IRCd public IP and port combination.

Breakdown

OPM {

# …

blacklist {

name = "P.H.G.F.E.ip-port.exitlist.torproject.org";Here you specify your server’s public IP, E.F.G.H, in reverse as H.G.F.E as well as the port your IRCd is listening on, P. BOPM will prepend the IP of the IRC client which connects, A.B.C.D, in reverse order as D.C.B.A when it checks if the client is in this TorDNSEL.

type = "A record reply";This specifies that BOMP should take the IP address the DNSBL returns and interpret that as a response. DNSBLs generally use IPs in the reserved localhost range, 127.0.0.0/8, to avoid pointing to IPs owned by third parties.

reply {

2 = "Tor exit server";

};This is the list of potential DNSBL responses which you anticipate from TorDNSEL. If the DNSBL returns NXDOMAIN (which means, “I don’t know about this doain”), BOPM will ignore the answer and assume the client is not in the DNSBL. However, if the server responds with an IP such as 127.0.0.2, BOPM will subtract 127.0.0.0 from the IP and then look for the result 2 in this reply list. If it finds an entry, it performs the action in kline discussed below.

TorDNSEL currently only defines two possible responses. NXDOMAIN indicates that the node would not connect to E.F.G.H:P on behalf of a Tor client. 127.0.0.2 or, as BOPM interprets it, 2 indicates that there is a Tor exit node at A.B.C.D which is willing to connect to your IRCd.

ban_unknown = yes;This line states that, if the DNSBL responds with an IP other than those handled in the reply block, it should assume that the client still should be banned. The TorDNSEL guide states Other A records inside net 127/8, except 127.0.0.1, are reserved for future use and should be interpreted by clients as indicating an exit node.

This means that the TorDNSEL project reserves the right to add a new response, such as 127.0.0.3, which would indicate a subtly different sort of tor exit node. Until this new response is defined, all we know is that the IRC client probably should be banned by BOPM.

# GZLINE issuing a 7-day network-wide zline with UnrealIRCd-compatible syntax

kline = "GZLINE *@%i 7d :You are connecting from a Tor exit node willing to connect to E.F.G.H:P";This is the IRC command which BOPM will issue when a client is listed in TorDNSEL. The above command will set a network-wide ban on the user’s IP which will last for 7 days using UnrealIRCd‘s syntax. A Global Z:Line is an efficient ban as the client’s connection can be closed by the IRCd before the IRCd looks up the client’s hostname. The reason listed with the GZ:Line is formulated so that the IRC user will understand exactly why he was banned.

};

# …

}; Be careful when editing your bopm.conf. Don’t forget any semicolons; even the ones after closing curly braces (}) are ncessary. If you’re reading this guide, you hopefully don’t need this advice ;-).

Testing

Once you have added the necessary configuration directives to your bopm.conf, you should test and check that BOPM catches the Tor exit nodes which are willing to connect to your IRCd. If BOPM was already running, do not forget to rehash it (BOPM’s readme suggests that /KILL BOPM (rehashing) is a convenient way to force BOPM to reread its configuration and reconnect). The following uses BOPM’s in-channel command interface to ask BOPM to scan an IP and check if it would be banned if a client connected from that IP. This requires that you have properly configured BOPM to join a channel with an IRC::channel block. An alternative test would be to just connect to your network through Tor, but that is probably more involved.

To check if your BOPM would detect a Tor IP, first find a Tor exit node (if using list list, ensure to choose an IP for which the “Exit Node?” column has “YES”). Then join the channel where BOPM is and issue the command BOPM check IP, where you replace BOPM with the nickname your BOPM bot is using and replace IP with the Tor exit node IP you looked up. A successful detection will look something like the following:

-!- BOPM2 [~bopm@Clk-NNNNNNNN] has joined #opers <&binki> BOPM2 check A.B.C.D < BOPM2> CHECK -> Checking 'A.B.C.D' for open proxies on all scanners < BOPM2> CHECK -> DNSBL -> A.B.C.D appears in BL zone 6667.H.G.F.E.ip-port.exitlist.torproject.org (Tor exit server) < BOPM2> CHECK -> DNSBL -> A.B.C.D appears in BL zone 6697.H.G.F.E.ip-port.exitlist.torproject.org (Tor exit server) < BOPM2> CHECK -> DNSBL -> A.B.C.D does not appear in BL zone 6900.H.G.F.E.ip-port.exitlist.torproject.org < BOPM2> CHECK -> DNSBL -> A.B.C.D appears in BL zone 7000.H.G.F.E.ip-port.exitlist.torproject.org (Tor exit server) < BOPM2> CHECK -> All tests on A.B.C.D completed.

In this scenario, the port 6900 was inside of a reject range policy on the Tor exit node I selected. For some odd reason, it seems that this port is part of a range which is commonly disabled in Tor exit nodes. Yet, the Tor exit node I chose admits that it is willing to connect to my IRCd still and will be banned because of one of the other OPM::blacklist blocks I have defined, such as the one for port 6667.

In your own tests, you might encounter Tor exit nodes which BOPM does not flag as needing to be banned. There are multiple reasons for this. First of all, you may have selected a Tor exit node with policies which disallow Tor clients to access IRC through it. Thus, you must try with multiple exit nodes randomly selected from some listing of Tor exit nodes before despairing. If you have checked multiple hosts and your BOPM refuses to recognize them, you may have misconfigured your BOPM’s blacklist entry. Double-check that you have put your correct server’s public IP in reverse order properly along with the correct port in the blacklist::name entry. Test that BOPM’s DNS is working by looking up D.C.B.A.P.H.G.F.E.ip-port.exitlist.torproject.org, perhaps using the getent hosts or dig tools. Remember to rehash BOPM (by /killing it with your /oper powers perhaps) after editing bopm.conf.

I was introduced to the bash builtin /dev/tcp by warg the other day on x-tab#chat. He explained a basic use of this device by demonstrating how to download wget’s compressed tarball. The download process itself can be done with pure bash, but some post-processing of the downloaded file must be done to remove HTTP headers. I document warg’s application of /dev/tcp here because I found the idea fascinating and want this documentation for myself ;-).

Connecting and Downloading

To read about the /dev/tcp builtin for yourself, check out the following:

$ info '(bash) Redirections'

With the exec line we initiate the connection, allocating a file descriptor and storing the numeic file descriptor into the HTTP_FD variable. Then, with the echo line, we send an HTTP request through the descriptor to the server. After sending the request, we process the server’s response with the sed line which skips over the HTTP headers sent by the server and stows the results into wget-latest.tar.gz. Note that this last command will sit around for a while. It is with this command that the builk of the data transfer is performed. And, since you’re using shell redirections to download the file, you cannot see the download progress. Instead, wait for the command to complete. This also involves waiting for the server to time out your connection since it supports pipelining. After this process is completed, the wget-latest.tar.gz file is as your disposal.

$ WGET_HOSTNAME='ftp.gnu.org'

$ exec {HTTP_FD}<>/dev/tcp/${WGET_HOSTNAME}/80

$ echo -ne 'GET /gnu/wget/wget-latest.tar.gz HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: '\

${WGET_HOSTNAME}'\r\nUser-Agent: '\

'bash/'${BASH_VERSION}'\r\n\r\n' >&${HTTP_FD}

$ sed -e '1,/^.$/d' <&${HTTP_FD} >wget-latest.tar.gz

Now you have a wget source tarball on your machine. As long as you have tar and a compiler on the machine, you are well on your way to downloading stuff using a self-compiled wget. In the commands above, you may replace “gz” with “bz2” or “lzma” for smaller downloads if the machine you’re using has bzip2 or xz-utils installed. And, of course, it should not be too hard to repurpose the above code to download a particular version of wget or even a completely unrelated software package.

Please feel free to point out problems with this approach or give pointers on porting this to other environments :-).

]]>

There are numerous guides about setting up Google Voice and an incoming sip number for free outgoing calling. Sadly, all of the guides I found were written for FreePBX or some other Asterisk bundle, and also used a shell script to do much of the work (scary!). I have compiled the minimal amount that you need to put in your asterisk conf files to make things work, GUI-free and variant-independent.

Prerequisites

First off, you need a sip number. I recommend sipgate or ipkall (I use sipgate, it’s much more user-friendly). If you google around, you’ll find out how to set up your sipgate/ipkall number as an incoming number in asterisk, I won’t waste time covering it here.

Secondly, you need a google voice number. Once you get said number, turn off call presentation. Also, assign the account a password that you don’t mind having plaintext in a conf file. In addition, you must add your incoming sip number as a phone in google voice. I’d recommend connecting a softphone to your sip number to set this up with google’s verification call, or redirect all incoming calls in Asterisk to your extension.

Thirdly, you need pygooglevoice. Download and install it, or use python’s easy_install command.

The outgoing rule

Now for the actual configuration. First you need to set up an outgoing call rule, so all calls to the outside world (in this case, 10-digit numbers preceded with a “9”) are directed though google voice.

[CallingRule_LocalCalls]

exten = _9XXXXXXXXXX,1,Goto(custom-gv,${EXTEN:-10},1)

Explanation: Any outgoing 10-digit number prefixed with a 9 will match this rule and go to the custom-gv section which we will set up later. The number that was dialed is passed (the “-10” excludes the 9 prefix from this) at the first dialplan rule.

The GV dialer

Now we need to set up the custom-gv section:

[custom-gv]

exten => _X.,1,Verbose(0, Custom-GV Preparing to call and park call at number ${EXTEN})

exten => _X.,n,Wait(1)

exten => _X.,n,Playback(pls-wait-connect-call)

exten => _X.,n,System(gvoice -e [email protected] -p GVPassword call ${EXTEN} IncomingNum &)

exten => _X.,n,Set(PARKINGEXTEN=701)

exten => _X.,n,Park()

Explanation: After you dial an outgoing number, you’ll be dropped in here. The Verbose() function tosses some output in debug level 0 and up (see the console for this output). The System() command dials the number with google voice. Make sure you change the items in strikethrough to your own personal information. The call is then parked on extension 701 (70X extensions for parking are default. Switch to your parking extension range if you are using non-default options).

Routing GV callbacks

Now you need to set up an incoming call rule. Direct all incoming calls from your sip number at this rule.

[incoming-call-sifter]

exten = s,1,NoOp(CIDredirect)

exten = s,2,Verbose(0, Got incoming CID ${CALLERID(num)}, redirecting…)

exten = s,3,GotoIf($[“${CALLERID(num)}” == “GVNumber“]?custom-park,s,1)

exten = s,4,Goto(section-to-route-normal-incoming-calls,s,1)

Explanation: If your google voice number rings your PBX, you know that it’s connecting you to the call you just dialed, so we need to reconnect it to the extension you dialed from. We’ll handle linking of the incoming GV call and your outgoing call (which is now parked) in the next section (custom-park).

Bringing it all together

The custom-park section links a google voice incoming call (which is actually ringing the person you originally dialed) with your original outgoing call (which is parked).

[custom-park]

exten => s,1,Verbose(0, Got incoming GV Callback! Connecting to your original outgoing call…)

exten => s,2,ParkedCall(701)

Explanation: After you dialed your external number, your call was parked as google voice started dialing the other number. This section joins your outgoing call with google voice’s incoming call, so you are connected to the party you originally dialed.

You’re done!

[pullquote]Have comments, questions, or need clarification? Leave a comment![/pullquote]

Well that turned out to be a bit longer than I expected, but if you know what you’re doing, you can just ignore the italicized text.

]]>As a Gentoo user, I value the ability to compile and install things from source. Yet I don’t want the messiness of a completely manual “distribution” such as LFS. Yet I feel like I’m missing out of a big chunk of the GNU/Linux experience when I have to tell people that I’ve only ever used Gentoo. Also, if one wants to make his package available from multiple distributions, he may find more success if he is able to facilitate creation of the binary packages for these other distributions.

Thus, I have committed sys-apps/pacman into Sunrise. I still have to get permission to commit a few fixes (hopefully by tomorrow). Also, archlinux’s take on mirrorselect, reflector, has been committed but awaits review. When these things get through, the following may actually be worth something:

I have attempted to write a guide to setting up an archlinux chroot on Gentoo. Don’t actually try the guide until about a week from now, when my stuff clears review, of course ;-). However, in the meantime, I would gladly accept:

- Technical criticisms

- (if you are tommy[d], please ignore the following) Alerts about the misuse of the apostrophe or general grammatical problems

- Documentation storage format suggestions — I suppose it would be a good exercise for me to learn docbook someday. Should I start now?

The problem: you have a computer sitting behind a firewall. You want to access it from a different location, but you don’t have the ability to forward any ports to it. The answer: SSH tunneling.

The Solution

Using an SSH tunnel, you can reverse-forward ports from one computer to another. To do this, you will need a computer running linux and sshd to reverse-forward the ports to. It is very convenient if this is the computer you will be using to access the remote machine. Otherwise, additional steps must be taken.

The Setup

The easiest way to set up and maintain a reverse port-forwarding tunnel is with ohnobinki’s insurgent script. The script allows you to specify a remote host and the ports you want to reverse-forward. To start off, create a new user on your system, such as insurgent. Log in or start a shell as this user. Assuming you have mercurial installed, run:

hg clone https://ohnopublishing.net/hg/insurgent

Now cd to the newly created insurgent/bin directory. Finally, place the contents of insurgent/share/contab.txt into your crontab (use crontab -e to edit your crontab).

Now you simply need to configure the script. To do so, open insurgent.sh in your favorite editor, and update the REMOTE_HOST and other variables. The format for ports is [remoteport]:hostname:[localport] (ssh(1) ). I recommend starting with reverse-fowarding SSH (port 22), a vnc session (590x where x is the VNC display number), and nfs.

If you have not done so already, you need to set up passwordless public key authentication for the new insurgent user.

You’re Done!

If you’ve gotten this far, you may be ready to go. You should be able to access any port on your insurgent box via the corresponding port on your local box. Have any problems? Drop some comments below or pop into irc.ohnopub.net#protofusion and speak to ohnobinki or normaldotcom.