[Chris Borge] has made (and revised) many of his own tools using a combination of 3D printing and common hardware, and recently decided to try metal casting. Having created his own tapping arm, he tries his hand at aluminum casting to create a much more compact version out of metal. His video (embedded below) really shows off the whole process, and [Chris] freely shares his learning experiences in casting his first metal tool.

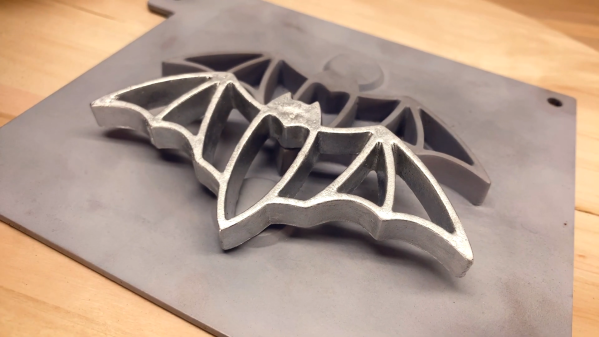

The result looks great and is considerably smaller in stature than the 3D-printed version. However, the workflow of casting metal parts is very different. The parts are much stronger, but there is a lot of preparation and post-processing involved.

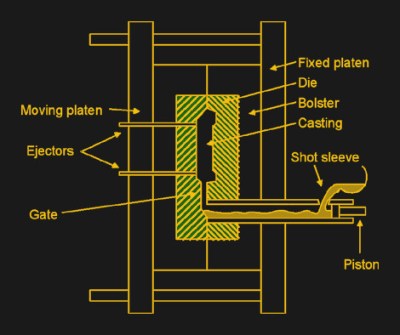

The key to making good castings is mold preparation. [Chris] uses green sand (a mixture of fine sand and bentonite clay – one source of the latter is ground-up kitty litter) packed tightly around 3D printed parts inside a frame. The packed sand holds its shape while still allowing the original forms to be removed and channels to be cut, creating a two-part mold.

His first-time castings have a rough surface texture, but are perfectly serviceable. After some CNC operations to smooth some faces and drill some holes, the surface imperfections are nothing filing, filler, and paint can’t handle.

To cast molten metal, there really isn’t any way around needing a forge. Or is there? We have seen some enterprising hackers repurpose microwave ovens for this purpose. One can also use a low-temperature alloy like Rose’s Metal, or eschew molten liquid altogether and do cold casting, which uses a mixture of resin and metal powder instead.

The design files for [Chris]’s tapping arm are available from links in the video description, and he also helpfully provides links to videos and resources he found useful. Watch it in the video, embedded just below.

Continue reading “3D Printing And Metal Casting Are A Great Match”