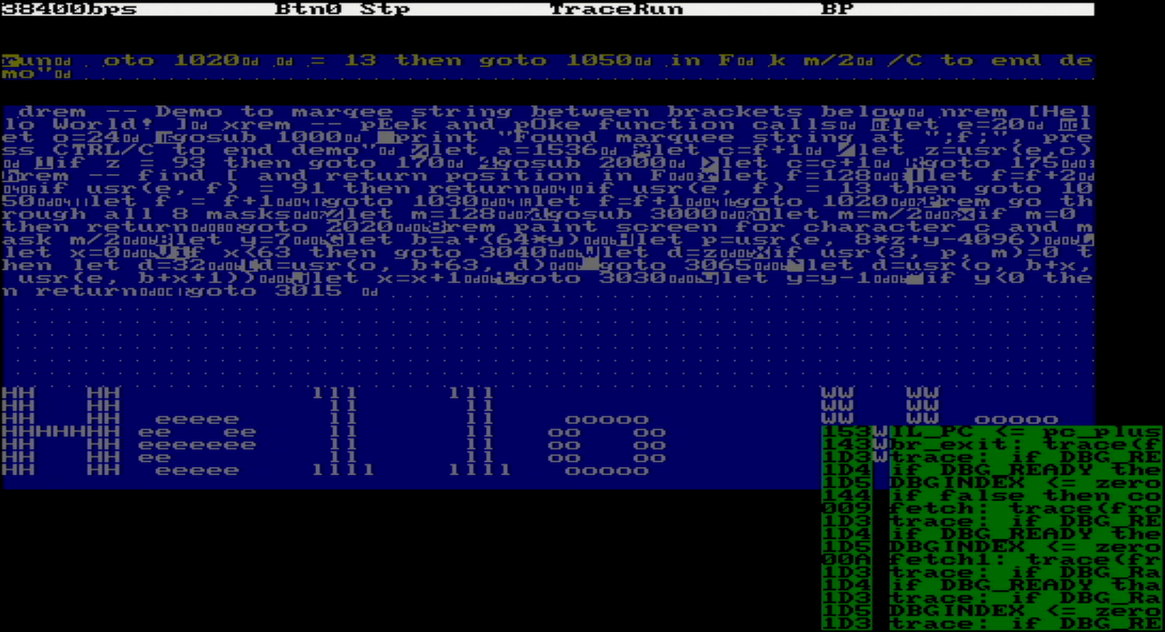

Update 2025-12-11 - the Basic CPU now comes in 4 flavors: original and extended interpreter, 16 or 32 bit. Interpreter version can be changed during run-time, and word width during build-time, see project logs.

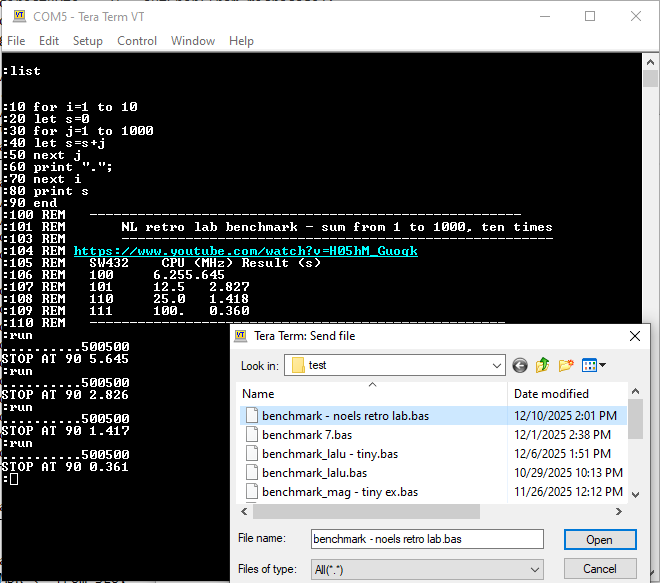

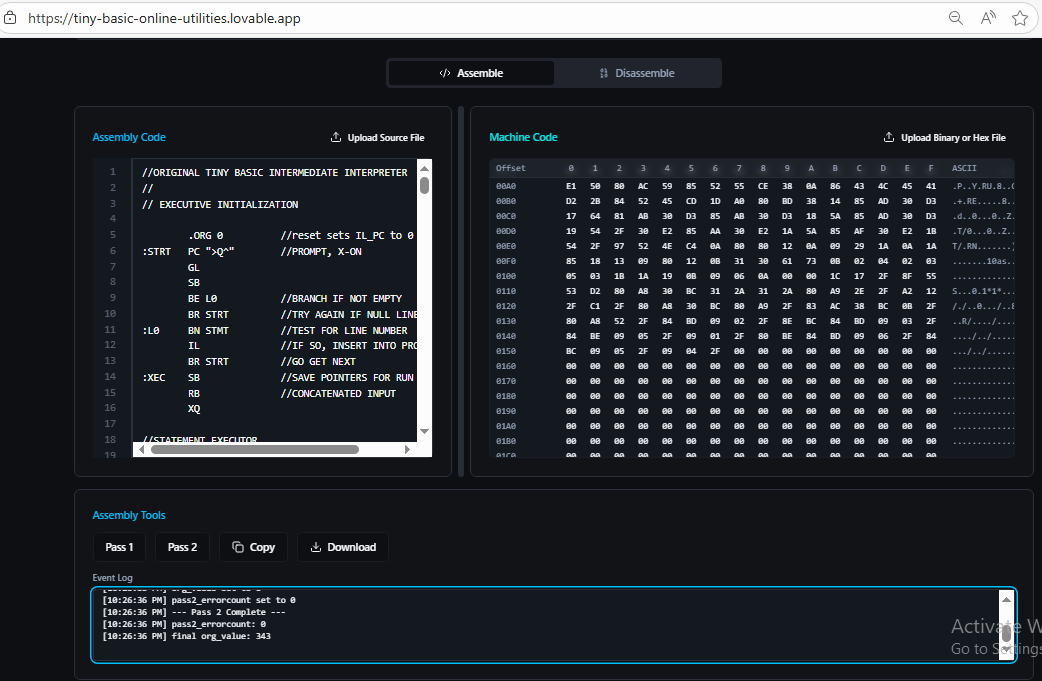

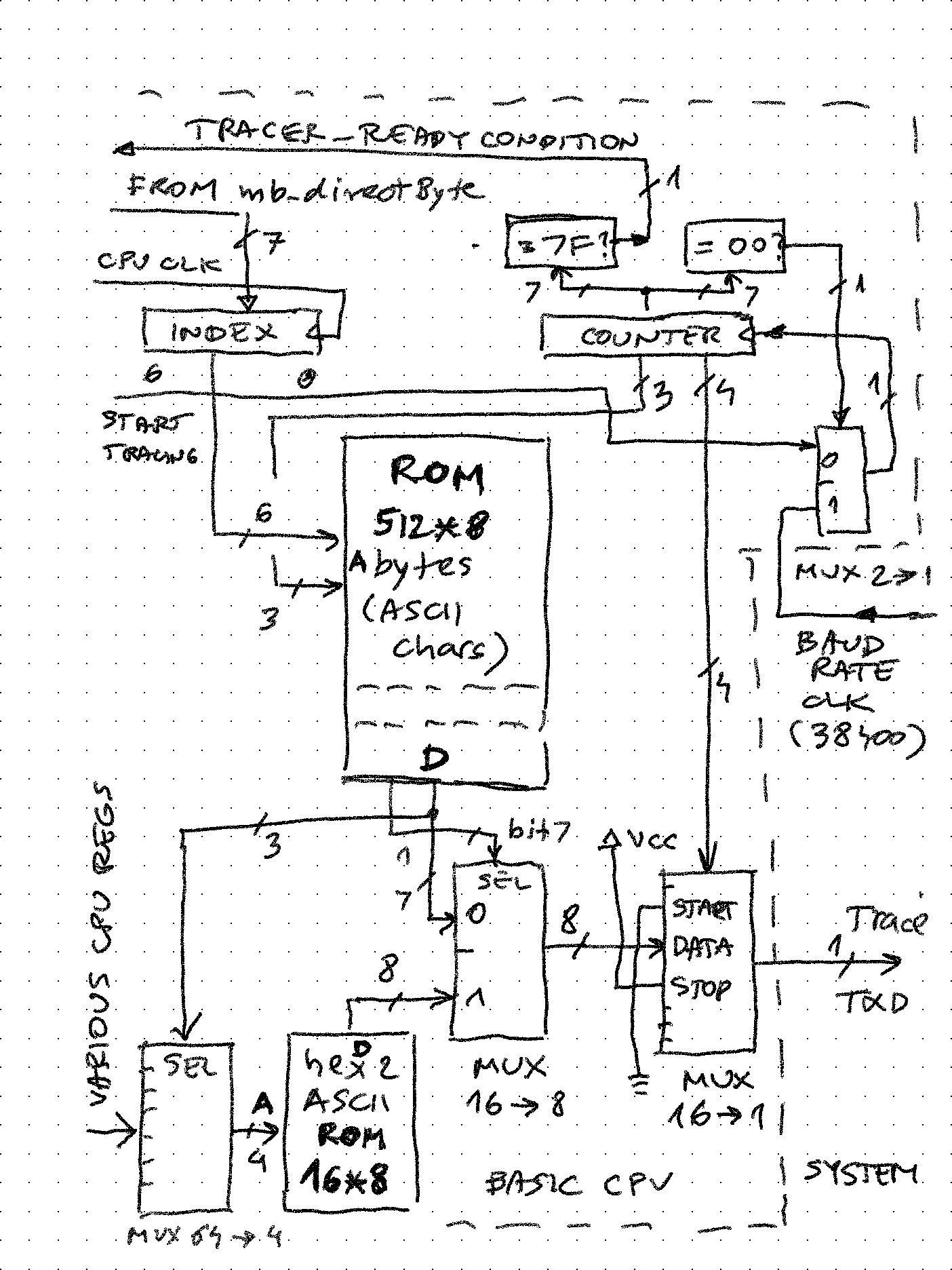

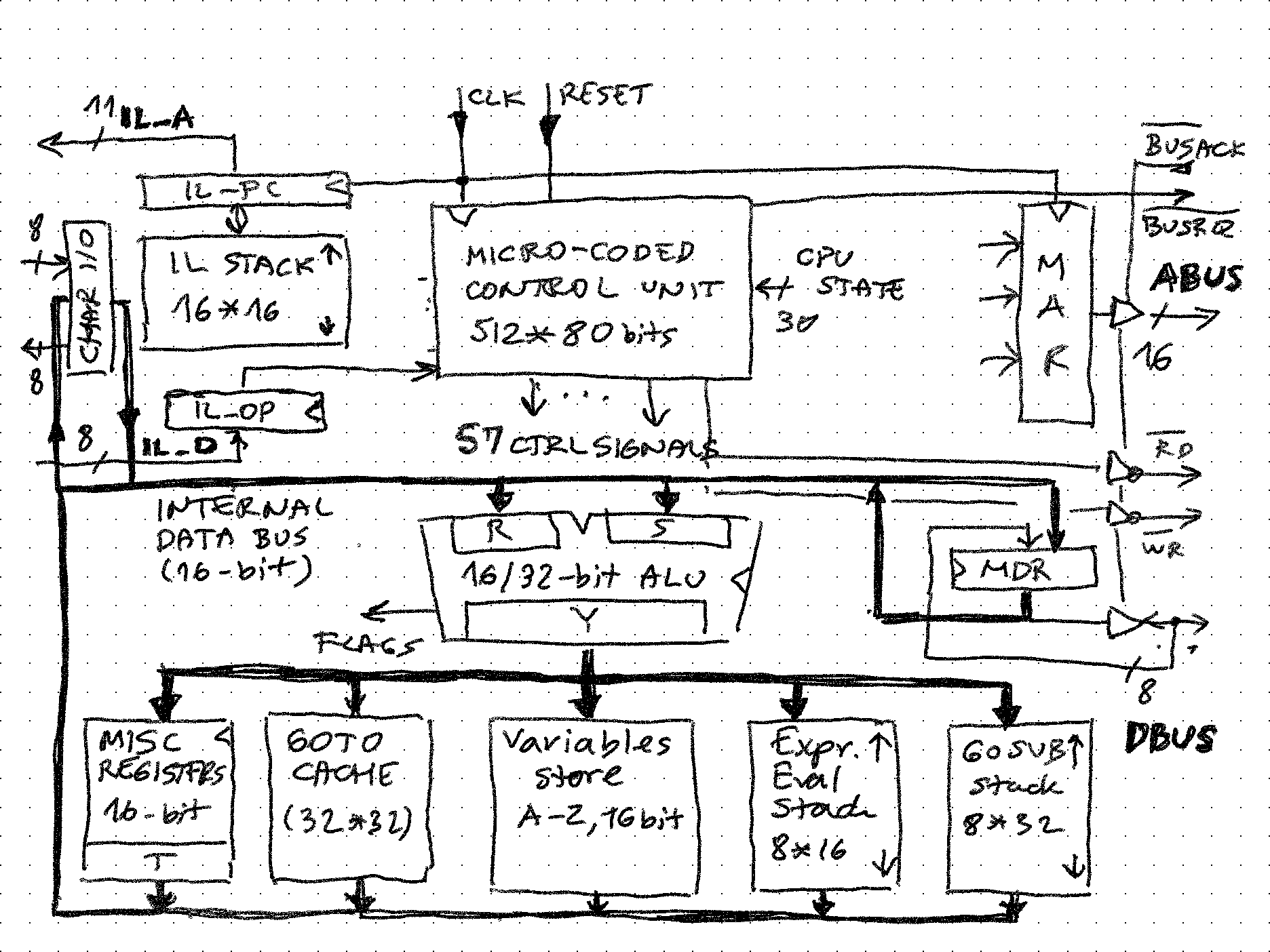

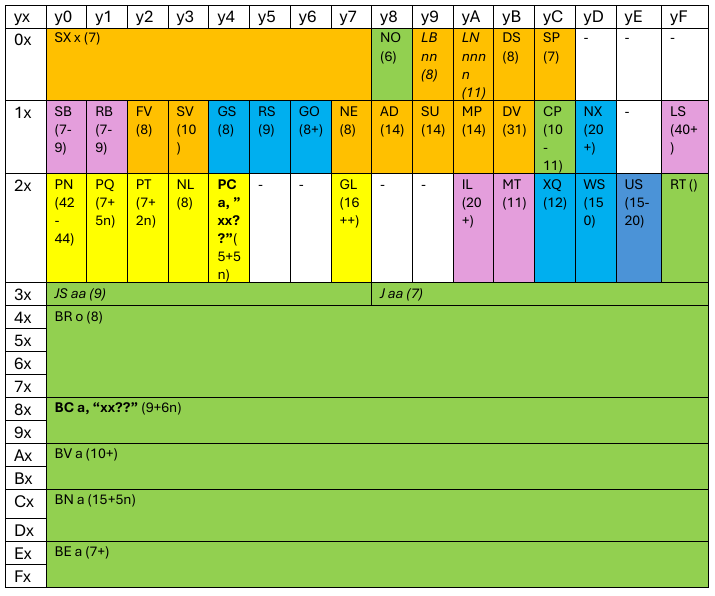

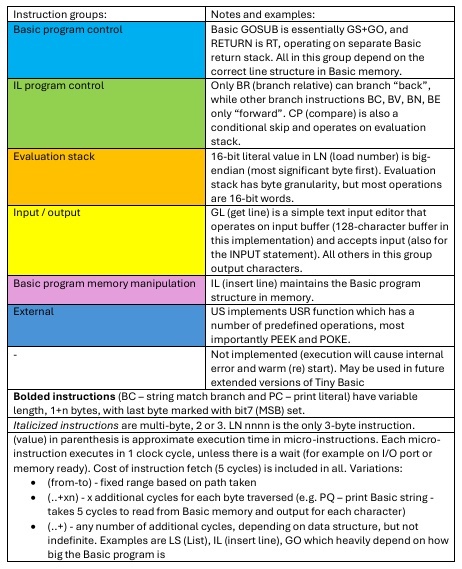

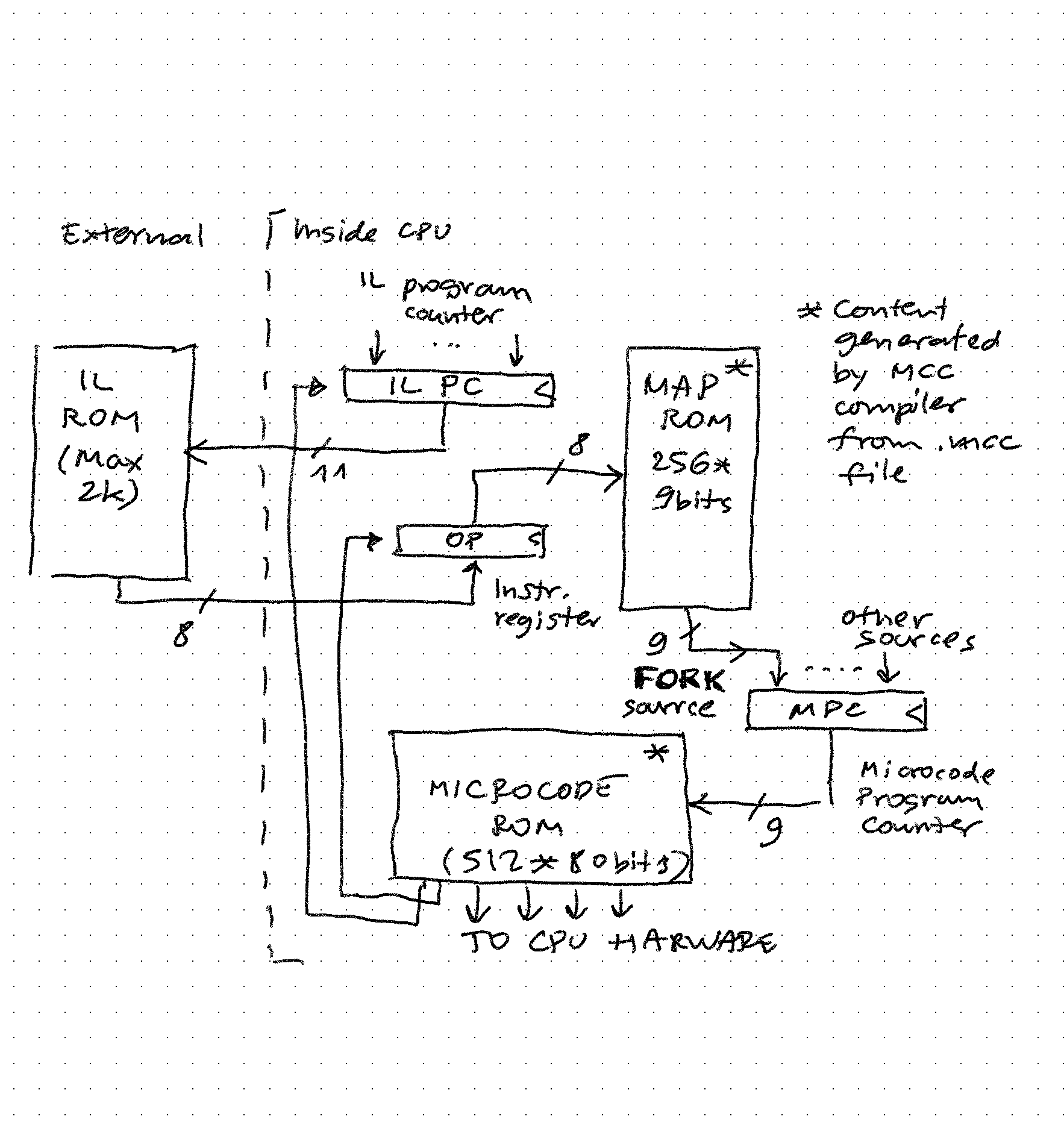

Homebrew CPUs are fun and fascinating - in implementations they span everything from relays to state of the art FPGAs, and in complexity and architecture they go from simplest one instruction machines to complex pipelined, superscalar processors. Where they often fail is going beyond demonstrating functionality. Writing any software for unique CPU requires much more time and different skills than designing and implementing an original CPU. This seems obvious, but I re-learned the lesson on my own project too. As a result, few end up with even working monitor / assembler, not to mention some higher level programming language. What if we would reverse the order? Start with well known and accessible piece of software like Basic and build the CPU around it? The intermediary steps could then be used to replicate and make custom CPUs run some simple variant of Basic. Tiny Basic variant using intermediate / interpretive language (IL) - a programming masterpiece devised and implemented 50 years ago by folks in People's Computer Company - is especially suited to this because it is requires implementation of only about 40 operations / instructions in machine language of the homebrew CPU and voila - Basic will be running on it! In this project, this implementation has been done using a micro-coded machine extended with all the registers and stacks needed to execute those 40 instructions. Following the microcode, it is possible to see the implementation algorithm, as well as the power of micro-coding. Another secret goal was to see if I could maybe have the fastest running Basic ever :-) by tweaking the CPU implementation and microcode and measuring against an old benchmark.

zpekic

zpekic