Practical Introduction to Data Science with Python

Anand S Menon, Kannan K, 06-07-2021

Agenda

1. Introduction to Data Science¶

1.1 What is Data Science ?

1.2 Why do we need Data Science ?

1.3 Brief Overview of Topics

1.3.1 Big Data Analytics

1.3.2 Machine Learning & Deep Learning2. Pythonic way of Data Science¶

2.1 Brief Intro to Python Programming Language

2.2 Python for Data Science

2.3 Data Processing, Statistical analysis and Visualization

2.3.1 numpy, pandas, scipy

2.3.2 matplotlib, seaborn, plotly

2.4 Model Building Frameworks

2.4.1 Scikit Learn, Tensorflow, Pytorch3. Approaching a Tabular(Structured) Problem¶

3.1 Understanding the Problem

3.2 Exploratory Data Analysis

3.2 Data Preprocessing

3.3 Feature Engineering

3.4 Model Building and Inference4. Approaching a Text (NLP) Problem¶

4.1 Importance of solving NLP problems

4.2 Applications of NLP

4.3 Intro to NLP

4.4 NLP using python

4.5 Approaching real life NLP problem5. Approaching a Vision Problem (Hands On)¶

4.1 An introduction to computer vision

4.1.1 What is Computer Vision?

4.1.2 How is computer vision used today?

4.2 Image Processing

4.2.1 Point Operators

4.2.1.1 Pixel Transforms

4.2.1.2 Color Transforms

4.2.1.3 Compositing and matting

4.2.1.4 Histogram Equalization

4.2.2 Linear Filtering

4.2.2.1 Separable Filtering

4.2.2.2 Band Pass and Steerable Filters

4.2.3 More neighborhood operators

4.2.3.1 Non-linear filtering

4.2.3.2 Bilateral filtering

4.2.3.3 Binary Image processing

4.2.4 Fourier Transforms

4.2.4.1 Two-dimensional Fourier Transforms

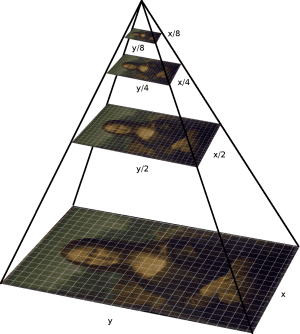

4.2.5 Pyramid and wavelets

4.2.5.1 Interpolation

4.2.5.2 Decimation

4.2.5.3 Multi-resolution representations

4.2.5.4 Wavelts

4.2.6 Geometrics transformations

4.2.6.1 Parametric transformations

4.2.6.2 Mesh-based warping

4.3 OpenCV Library [Hands On]

4.3.1 Introduction

4.3.2 Changing colorspaces

4.3.3 Geometric transformations of Images

4.3.4 Image thresholding

4.3.5 Smoothing Images

4.3.6 Morphological Transformations

4.3.7 Image Gradients

4.3.8 Canny Edge Detection

4.3.9 Image Pyramids

4.3.10 Contours

4.3.11 Histograms

4.3.12 Image Transforms1. Introduction to Data Science

1.1 What is Data Science?

"Data science is an interdisciplinary field that uses scientific methods, processes, algorithms and systems to extract knowledge and insights from structured and unstructured data, and apply knowledge and actionable insights from data across a broad range of application domains. Data science is related to data mining, machine learning and big data." - Wikipedia

In layman's terms it is a combination of different fields like computer science, maths, statistics, domain knowledge ..etc, which works together in order to fetch, process and evaluate huge amount of data for better bussiness decision making.

1.2 Why do we need Data Science?

The answer to that question is pretty simple. Data Science would help companies in saving billions of dollar by taking right decisions at right time with assistance of data.

Data Science is all about data and making sense of data will reduce the horrors of uncertainties for any organizations.

Did you know that Southwest Airlines, at one point, was able to save $100 million by leveraging data? They could reduce their planes’ idle time that waited at the tarmac and drive a change in utilizing their resources. In short, today, it is not possible for any business to imagine a world without data.

Data statistics facts as of 2021

"Google gets over 3.5 billion searches daily."

"WhatsApp users exchange up to 65 billion messages daily."

"In 2020, every person generated 1.7 megabytes per second"

"80-90% of the data we generate today is unstructured."

"On average, 500 million tweets are shared every day. This can be further broken down to 6,000 tweets per second, 350,000 tweets per minute, and around 200 billion tweets every year."

The above facts clearly indicates the data explosion and we need ways to ingest, validate, process and infer data which all comes under the Data Science umbrella

Data Explosion

Data is growing at pace we have not imagined before

1.3.1 Big Data Analytics

What is big data exactly? It can be defined as data sets whose size or type is beyond the ability of traditional relational databases to capture, manage and process the data with low latency. Characteristics of big data include high volume, high velocity and high variety

Big data analytics is the use of advanced analytic techniques against very large, diverse big data sets that include structured, semi-structured and unstructured data, from different sources, and in different sizes from terabytes to zettabytes.

With big data analytics, you can ultimately fuel better and faster decision-making, modelling and predicting of future outcomes and enhanced business intelligence.

Some of commonly used frameworks are Apache Hadpoop, Apacha spark, Cassandra ..etc

1.3.2 Machine Learning & Deep Learning

* Machine Learning involves algorithms that learn from patterns of data and then apply it to decision making.

* Deep Learning is able to learn through processing data on its own using neural nets and is quite similar to the human brain where it identifies something, analyse it, and makes a decision.

2.Pythonic way of data science¶

Brief Intro to Python Programming Language¶

Python is an interpreted, high-level, general-purpose programming language. It is is dynamically typed and garbage-collected.

One of the most popular and fastest growing languages programming language in the world (StackOverflow survey 2020). First appeared on February 1991 (30 years ago).

Highly efficient to write and programs tends to be clear and readable. well suitble for application like data science and web development.

Used in a wide range of fields, from healthcare to finance to VFX and AI.

The Father Of Python: Guido Van Rossum

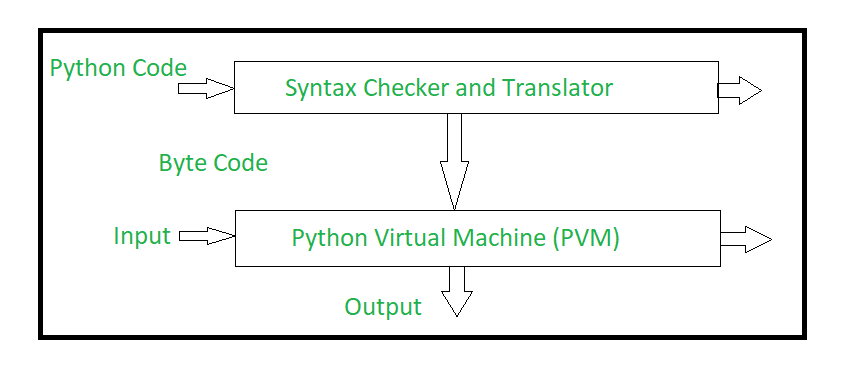

Internal working of Python

Python way of Data Science¶

Python provide great functionality to deal with mathematics, statistics and scientific function. It provides great libraries to deals with data science application.

- It’s Flexible

- It’s Easy to Learn

- It’s Open Source

- It’s Well-Supported

As is the case with many other programming languages, it’s the available libraries that lead to Python’s success: some 72,000 of them in the Python Package Index (PyPI) and growing constantly.

Python

# print the integers from 1 to 0

for i in range(1,10):

print(i)

Java

// print the integers from 1 to 9

for(int i=1;i<10;i++){

System.out.println(i);

}

Python hanldes a lot of memory automatically, so less time dealing with pointers and references and so on than other lanugages like C++.

Developer who prioritize ease of programming over execution speed¶

Python runs slower than other common languages like C++ or Java, but its often quick to write (three to five times faster than Java and five to ten times than C++).

One of the main reason why Python is used in "support language" for tasks like build control, automated testing and bug tracking. For the same reason used for prototyping.

Developers working with text and numbers¶

Python have powerful String anf List manipulation functions. Its a great tool for exploring data.

Avoiding the need for compiling makes it easier to run interactively on data for step by step manipulation. (Just like this Jupyter notebook).

Python's core functionality can be extended with a huge number of packages which are mainly used by the scientific and academic communities as well as engineering.

These include the Numpy(mathematical function and data analysis), SciPy(for science), Matplotlib(data visualization) and Pandas(data analysis) and more recently Tensorflow and Keras (Machine Learning/AI) and tens of thousands of others.

Web Developers¶

Backend development for webapplication. Python has built-in supports for common protocols like HTML, XML and Json.

Frameworks like Django, Flask and Bottle are widely used. For example Reddit's backend in Python.

The Zen of Python¶

The Zen of Python is a collection of 19 "guiding principles".

Some are:

- Readability counts.

- Simple is better than complex

- There should be one - and preferably only one - obvious way to do it.

Intro to Data Processing, Statistical analysis and Visualization libraries¶

A Brief Note on Python Versions¶

As of Janurary 1, 2020, Python has officially dropped support for python2.

!python --version

Python 3.7.11

Numpy is the core library for scientific computing in Python. It provides a high-performance multidimensional array object, and tools for working with these arrays.

To use Numpy, we first need to import the numpy package:

import numpy as np

Arrays¶

A numpy array is a grid of values, all of the same type, and is indexed by a tuple of nonnegative integers. The number of dimensions is the rank of the array; the shape of an array is a tuple of integers giving the size of the array along each dimension.

We can initialize numpy arrays from nested Python lists, and access elements using square brackets:

a = np.array([1, 2, 3]) # Create a rank 1 array

print(type(a), a.shape, a[0], a[1], a[2])

a[0] = 5 # Change an element of the array

print(a)

<class 'numpy.ndarray'> (3,) 1 2 3 [5 2 3]

b = np.array([[1,2,3],[4,5,6]]) # Create a rank 2 array

print(b)

[[1 2 3] [4 5 6]]

print(b.shape)

print(b[0, 0], b[0, 1], b[1, 0])

(2, 3) 1 2 4

Numpy also provides many functions to create arrays:

a = np.zeros((2,2)) # Create an array of all zeros

print(a)

[[0. 0.] [0. 0.]]

b = np.ones((1,2)) # Create an array of all ones

print(b)

[[1. 1.]]

c = np.full((2,2), 7) # Create a constant array

print(c)

[[7 7] [7 7]]

d = np.eye(2) # Create a 2x2 identity matrix

print(d)

[[1. 0.] [0. 1.]]

e = np.random.random((2,2)) # Create an array filled with random values

print(e)

[[0.18008187 0.07831069] [0.3829961 0.69663983]]

Array indexing¶

Numpy offers several ways to index into arrays.

Slicing: Similar to Python lists, numpy arrays can be sliced. Since arrays may be multidimensional, you must specify a slice for each dimension of the array:

import numpy as np

# Create the following rank 2 array with shape (3, 4)

# [[ 1 2 3 4]

# [ 5 6 7 8]

# [ 9 10 11 12]]

a = np.array([[1,2,3,4], [5,6,7,8], [9,10,11,12]])

# Use slicing to pull out the subarray consisting of the first 2 rows

# and columns 1 and 2; b is the following array of shape (2, 2):

# [[2 3]

# [6 7]]

b = a[:2, 1:3]

print(b)

[[2 3] [6 7]]

A slice of an array is a view into the same data, so modifying it will modify the original array.

print(a[0, 1])

b[0, 0] = 77 # b[0, 0] is the same piece of data as a[0, 1]

print(a[0, 1])

2 77

You can also mix integer indexing with slice indexing. However, doing so will yield an array of lower rank than the original array.

# Create the following rank 2 array with shape (3, 4)

a = np.array([[1,2,3,4], [5,6,7,8], [9,10,11,12]])

print(a)

[[ 1 2 3 4] [ 5 6 7 8] [ 9 10 11 12]]

Two ways of accessing the data in the middle row of the array. Mixing integer indexing with slices yields an array of lower rank, while using only slices yields an array of the same rank as the original array:

row_r1 = a[1, :] # Rank 1 view of the second row of a

row_r2 = a[1:2, :] # Rank 2 view of the second row of a

row_r3 = a[[1], :] # Rank 2 view of the second row of a

print(row_r1, row_r1.shape)

print(row_r2, row_r2.shape)

print(row_r3, row_r3.shape)

[5 6 7 8] (4,) [[5 6 7 8]] (1, 4) [[5 6 7 8]] (1, 4)

# We can make the same distinction when accessing columns of an array:

col_r1 = a[:, 1]

col_r2 = a[:, 1:2]

print(col_r1, col_r1.shape)

print()

print(col_r2, col_r2.shape)

[ 2 6 10] (3,) [[ 2] [ 6] [10]] (3, 1)

Boolean array indexing: Boolean array indexing lets you pick out arbitrary elements of an array. Frequently this type of indexing is used to select the elements of an array that satisfy some condition. Here is an example:

import numpy as np

a = np.array([[1,2], [3, 4], [5, 6]])

bool_idx = (a > 2) # Find the elements of a that are bigger than 2;

# this returns a numpy array of Booleans of the same

# shape as a, where each slot of bool_idx tells

# whether that element of a is > 2.

print(bool_idx)

[[False False] [ True True] [ True True]]

# We use boolean array indexing to construct a rank 1 array

# consisting of the elements of a corresponding to the True values

# of bool_idx

print(a[bool_idx])

# We can do all of the above in a single concise statement:

print(a[a > 2])

[3 4 5 6] [3 4 5 6]

Datatypes¶

Every numpy array is a grid of elements of the same type. Numpy provides a large set of numeric datatypes that you can use to construct arrays. Numpy tries to guess a datatype when you create an array, but functions that construct arrays usually also include an optional argument to explicitly specify the datatype. Here is an example:

x = np.array([1, 2]) # Let numpy choose the datatype

y = np.array([1.0, 2.0]) # Let numpy choose the datatype

z = np.array([1, 2], dtype=np.int64) # Force a particular datatype

print(x.dtype, y.dtype, z.dtype)

int64 float64 int64

You can read all about numpy datatypes in the documentation.

Array math¶

Basic mathematical functions operate elementwise on arrays, and are available both as operator overloads and as functions in the numpy module:

x = np.array([[1,2],[3,4]], dtype=np.float64)

y = np.array([[5,6],[7,8]], dtype=np.float64)

# Elementwise sum; both produce the array

print(x + y)

print(np.add(x, y))

[[ 6. 8.] [10. 12.]] [[ 6. 8.] [10. 12.]]

# Elementwise difference; both produce the array

print(x - y)

print(np.subtract(x, y))

[[-4. -4.] [-4. -4.]] [[-4. -4.] [-4. -4.]]

# Elementwise product; both produce the array

print(x * y)

print(np.multiply(x, y))

[[ 5. 12.] [21. 32.]] [[ 5. 12.] [21. 32.]]

# Elementwise division; both produce the array

# [[ 0.2 0.33333333]

# [ 0.42857143 0.5 ]]

print(x / y)

print(np.divide(x, y))

[[0.2 0.33333333] [0.42857143 0.5 ]] [[0.2 0.33333333] [0.42857143 0.5 ]]

# Elementwise square root; produces the array

# [[ 1. 1.41421356]

# [ 1.73205081 2. ]]

print(np.sqrt(x))

[[1. 1.41421356] [1.73205081 2. ]]

x = np.array([[1,2],[3,4]])

y = np.array([[5,6],[7,8]])

v = np.array([9,10])

w = np.array([11, 12])

# Inner product of vectors; both produce 219

print(v.dot(w))

print(np.dot(v, w))

219 219

You can also use the @ operator which is equivalent to numpy's dot operator.

print(v @ w)

219

# Matrix / vector product; both produce the rank 1 array [29 67]

print(x.dot(v))

print(np.dot(x, v))

print(x @ v)

[29 67] [29 67] [29 67]

# Matrix / matrix product; both produce the rank 2 array

# [[19 22]

# [43 50]]

print(x.dot(y))

print(np.dot(x, y))

print(x @ y)

[[19 22] [43 50]] [[19 22] [43 50]] [[19 22] [43 50]]

Numpy provides many useful functions for performing computations on arrays; one of the most useful is sum:

x = np.array([[1,2],[3,4]])

print(np.sum(x)) # Compute sum of all elements; prints "10"

print(np.sum(x, axis=0)) # Compute sum of each column; prints "[4 6]"

print(np.sum(x, axis=1)) # Compute sum of each row; prints "[3 7]"

10 [4 6] [3 7]

You can find the full list of mathematical functions provided by numpy in the documentation.

Apart from computing mathematical functions using arrays, we frequently need to reshape or otherwise manipulate data in arrays. The simplest example of this type of operation is transposing a matrix; to transpose a matrix, simply use the T attribute of an array object:

print(x)

print("transpose\n", x.T)

[[1 2] [3 4]] transpose [[1 3] [2 4]]

v = np.array([[1,2,3]])

print(v )

print("transpose\n", v.T)

[[1 2 3]] transpose [[1] [2] [3]]

pandas is a column-oriented data analysis API. It's a great tool for handling and analyzing input data, and many ML frameworks support pandas data structures as inputs. For a more complete reference, the pandas docs site contains extensive documentation and many tutorials.

Basic Concepts¶

The following line imports the pandas API and prints the API version:

from __future__ import print_function

import pandas as pd

pd.__version__

'1.1.5'

The primary data structures in pandas are implemented as two classes:

DataFrame, which you can imagine as a relational data table, with rows and named columns.Series, which is a single column. ADataFramecontains one or moreSeriesand a name for eachSeries.

The data frame is a commonly used abstraction for data manipulation. Similar implementations exist in Spark and R.

One way to create a Series is to construct a Series object. For example:

pd.Series(['San Francisco', 'San Jose', 'Sacramento'])

0 San Francisco 1 San Jose 2 Sacramento dtype: object

DataFrame objects can be created by passing a dict mapping string column names to their respective Series. If the Series don't match in length, missing values are filled with special NA/NaN values. Example:

city_names = pd.Series(['San Francisco', 'San Jose', 'Sacramento'])

population = pd.Series([852469, 1015785, 485199])

pd.DataFrame({ 'City name': city_names, 'Population': population })

| City name | Population | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | San Francisco | 852469 |

| 1 | San Jose | 1015785 |

| 2 | Sacramento | 485199 |

But most of the time, you load an entire file into a DataFrame. The following example loads a file with California housing data. Run the following cell to load the data and create feature definitions:

One way to create a Series is to construct a Series object. For example:

pd.Series(['San Francisco', 'San Jose', 'Sacramento'])

0 San Francisco 1 San Jose 2 Sacramento dtype: object

DataFrame objects can be created by passing a dict mapping string column names to their respective Series. If the Series don't match in length, missing values are filled with special NA/NaN values. Example:

city_names = pd.Series(['San Francisco', 'San Jose', 'Sacramento'])

population = pd.Series([852469, 1015785, 485199])

pd.DataFrame({ 'City name': city_names, 'Population': population })

| City name | Population | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | San Francisco | 852469 |

| 1 | San Jose | 1015785 |

| 2 | Sacramento | 485199 |

But most of the time, you load an entire file into a DataFrame. The following example loads a file with California housing data.

california_housing_dataframe = pd.read_csv("https://download.mlcc.google.com/mledu-datasets/california_housing_train.csv", sep=",")

california_housing_dataframe.describe()

| longitude | latitude | housing_median_age | total_rooms | total_bedrooms | population | households | median_income | median_house_value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 17000.000000 | 17000.000000 | 17000.000000 | 17000.000000 | 17000.000000 | 17000.000000 | 17000.000000 | 17000.000000 | 17000.000000 |

| mean | -119.562108 | 35.625225 | 28.589353 | 2643.664412 | 539.410824 | 1429.573941 | 501.221941 | 3.883578 | 207300.912353 |

| std | 2.005166 | 2.137340 | 12.586937 | 2179.947071 | 421.499452 | 1147.852959 | 384.520841 | 1.908157 | 115983.764387 |

| min | -124.350000 | 32.540000 | 1.000000 | 2.000000 | 1.000000 | 3.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.499900 | 14999.000000 |

| 25% | -121.790000 | 33.930000 | 18.000000 | 1462.000000 | 297.000000 | 790.000000 | 282.000000 | 2.566375 | 119400.000000 |

| 50% | -118.490000 | 34.250000 | 29.000000 | 2127.000000 | 434.000000 | 1167.000000 | 409.000000 | 3.544600 | 180400.000000 |

| 75% | -118.000000 | 37.720000 | 37.000000 | 3151.250000 | 648.250000 | 1721.000000 | 605.250000 | 4.767000 | 265000.000000 |

| max | -114.310000 | 41.950000 | 52.000000 | 37937.000000 | 6445.000000 | 35682.000000 | 6082.000000 | 15.000100 | 500001.000000 |

The example above used DataFrame.describe to show interesting statistics about a DataFrame. Another useful function is DataFrame.head, which displays the first few records of a DataFrame:

california_housing_dataframe.head()

| longitude | latitude | housing_median_age | total_rooms | total_bedrooms | population | households | median_income | median_house_value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -114.31 | 34.19 | 15.0 | 5612.0 | 1283.0 | 1015.0 | 472.0 | 1.4936 | 66900.0 |

| 1 | -114.47 | 34.40 | 19.0 | 7650.0 | 1901.0 | 1129.0 | 463.0 | 1.8200 | 80100.0 |

| 2 | -114.56 | 33.69 | 17.0 | 720.0 | 174.0 | 333.0 | 117.0 | 1.6509 | 85700.0 |

| 3 | -114.57 | 33.64 | 14.0 | 1501.0 | 337.0 | 515.0 | 226.0 | 3.1917 | 73400.0 |

| 4 | -114.57 | 33.57 | 20.0 | 1454.0 | 326.0 | 624.0 | 262.0 | 1.9250 | 65500.0 |

Another powerful feature of pandas is graphing. For example, DataFrame.hist lets you quickly study the distribution of values in a column:

california_housing_dataframe.hist('housing_median_age')

array([[<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot object at 0x7f559b178d50>]],

dtype=object)

Accessing Data¶

You can access DataFrame data using familiar Python dict/list operations:

cities = pd.DataFrame({ 'City name': city_names, 'Population': population })

print(type(cities['City name']))

cities['City name']

<class 'pandas.core.series.Series'>

0 San Francisco 1 San Jose 2 Sacramento Name: City name, dtype: object

print(type(cities['City name'][1]))

cities['City name'][1]

<class 'str'>

'San Jose'

print(type(cities[0:2]))

cities[0:2]

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

| City name | Population | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | San Francisco | 852469 |

| 1 | San Jose | 1015785 |

In addition, pandas provides an extremely rich API for advanced indexing and selection that is too extensive to be covered here.

Manipulating Data¶

You may apply Python's basic arithmetic operations to Series. For example:

population / 1000.

0 852.469 1 1015.785 2 485.199 dtype: float64

Modifying DataFrames is also straightforward. For example, the following code adds two Series to an existing DataFrame:

cities['Area square miles'] = pd.Series([46.87, 176.53, 97.92])

cities['Population density'] = cities['Population'] / cities['Area square miles']

cities

| City name | Population | Area square miles | Population density | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | San Francisco | 852469 | 46.87 | 18187.945381 |

| 1 | San Jose | 1015785 | 176.53 | 5754.177760 |

| 2 | Sacramento | 485199 | 97.92 | 4955.055147 |

Indexes¶

Both Series and DataFrame objects also define an index property that assigns an identifier value to each Series item or DataFrame row.

By default, at construction, pandas assigns index values that reflect the ordering of the source data. Once created, the index values are stable; that is, they do not change when data is reordered.

city_names.index

RangeIndex(start=0, stop=3, step=1)

cities.index

RangeIndex(start=0, stop=3, step=1)

Call DataFrame.reindex to manually reorder the rows. For example, the following has the same effect as sorting by city name:

cities.reindex([2, 0, 1])

| City name | Population | Area square miles | Population density | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Sacramento | 485199 | 97.92 | 4955.055147 |

| 0 | San Francisco | 852469 | 46.87 | 18187.945381 |

| 1 | San Jose | 1015785 | 176.53 | 5754.177760 |

SciPy¶

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from IPython.display import Image

The SciPy framework builds on top of the low-level NumPy framework for multidimensional arrays, and provides a large number of higher-level scientific algorithms. Some of the topics that SciPy covers are:

- Special functions (scipy.special)

- Integration (scipy.integrate)

- Optimization (scipy.optimize)

- Interpolation (scipy.interpolate)

- Fourier Transforms (scipy.fftpack)

- Signal Processing (scipy.signal)

- Linear Algebra (scipy.linalg)

- Sparse Eigenvalue Problems (scipy.sparse)

- Statistics (scipy.stats)

- Multi-dimensional image processing (scipy.ndimage)

- File IO (scipy.io)

Each of these submodules provides a number of functions and classes that can be used to solve problems in their respective topics.

To access the SciPy package in a Python program, we start by importing everything from the scipy module.

from scipy import *

If we only need to use part of the SciPy framework we can selectively include only those modules we are interested in. For example, to include the linear algebra package under the name la, we can do:

import scipy.linalg as la

Special functions¶

A large number of mathematical special functions are important for many computional physics problems. SciPy provides implementations of a very extensive set of special functions. For details, see the list of functions in the reference documention at http://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/special.html#module-scipy.special.

To demonstrate the typical usage of special functions we will look in more detail at the Bessel functions:

Integration¶

Numerical integration: quadrature¶

Numerical evaluation of a function of the type

$\displaystyle \int_a^b f(x) dx$

is called numerical quadrature, or simply quadature. SciPy provides a series of functions for different kind of quadrature, for example the quad, dblquad and tplquad for single, double and triple integrals, respectively.

from scipy.integrate import quad, dblquad, tplquad

Ordinary differential equations (ODEs)¶

SciPy provides two different ways to solve ODEs: An API based on the function odeint, and object-oriented API based on the class ode. Usually odeint is easier to get started with, but the ode class offers some finer level of control.

Here we will use the odeint functions. For more information about the class ode, try help(ode). It does pretty much the same thing as odeint, but in an object-oriented fashion.

For example, to use odeint, import it from the scipy.integrate module

from scipy.integrate import odeint, ode

Fourier transform¶

Fourier transforms are one of the universal tools in computational physics, which appear over and over again in different contexts. SciPy provides functions for accessing the classic FFTPACK library from NetLib, which is an efficient and well tested FFT library written in FORTRAN. The SciPy API has a few additional convenience functions, but overall the API is closely related to the original FORTRAN library.

To use the fftpack module in a python program, include it using:

from numpy.fft import fftfreq

from scipy.fftpack import *

Linear algebra¶

The linear algebra module contains a lot of matrix related functions, including linear equation solving, eigenvalue solvers, matrix functions (for example matrix-exponentiation), a number of different decompositions (SVD, LU, cholesky), etc.

Detailed documetation is available at: http://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/linalg.html

Optimization¶

Optimization (finding minima or maxima of a function) is a large field in mathematics, and optimization of complicated functions or in many variables can be rather involved. Here we will only look at a few very simple cases. For a more detailed introduction to optimization with SciPy see: http://scipy-lectures.github.com/advanced/mathematical_optimization/index.html

To use the optimization module in scipy first include the optimize module:

from scipy import optimize

Interpolation¶

Interpolation is simple and convenient in scipy: The interp1d function, when given arrays describing X and Y data, returns and object that behaves like a function that can be called for an arbitrary value of x (in the range covered by X), and it returns the corresponding interpolated y value:

Statistics¶

The scipy.stats module contains a large number of statistical distributions, statistical functions and tests. For a complete documentation of its features, see http://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/stats.html.

There is also a very powerful python package for statistical modelling called statsmodels. See http://statsmodels.sourceforge.net for more details.

Matplotlib¶

Matplotlib is a plotting library. In this section give a brief introduction to the matplotlib.pyplot module, which provides a plotting system similar to that of MATLAB.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

By running this special iPython command, we will be displaying plots inline:

%matplotlib inline

Plotting¶

The most important function in matplotlib is plot, which allows you to plot 2D data. Here is a simple example:

# Compute the x and y coordinates for points on a sine curve

x = np.arange(0, 3 * np.pi, 0.1)

y = np.sin(x)

# Plot the points using matplotlib

plt.plot(x, y)

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x7f558e85dd50>]

With just a little bit of extra work we can easily plot multiple lines at once, and add a title, legend, and axis labels:

y_sin = np.sin(x)

y_cos = np.cos(x)

# Plot the points using matplotlib

plt.plot(x, y_sin)

plt.plot(x, y_cos)

plt.xlabel('x axis label')

plt.ylabel('y axis label')

plt.title('Sine and Cosine')

plt.legend(['Sine', 'Cosine'])

<matplotlib.legend.Legend at 0x7f558e7e6950>

Subplots¶

You can plot different things in the same figure using the subplot function. Here is an example:

# Compute the x and y coordinates for points on sine and cosine curves

x = np.arange(0, 3 * np.pi, 0.1)

y_sin = np.sin(x)

y_cos = np.cos(x)

# Set up a subplot grid that has height 2 and width 1,

# and set the first such subplot as active.

plt.subplot(2, 1, 1)

# Make the first plot

plt.plot(x, y_sin)

plt.title('Sine')

# Set the second subplot as active, and make the second plot.

plt.subplot(2, 1, 2)

plt.plot(x, y_cos)

plt.title('Cosine')

# Show the figure.

plt.show()

You can read much more about the subplot function in the documentation.

Seaborn¶

Reference: Visualization-With-Seaborn

Seaborn. Seaborn provides an API on top of Matplotlib that offers sane choices for plot style and color defaults, defines simple high-level functions for common statistical plot types, and integrates with the functionality provided by Pandas DataFrames.

Seaborn Versus Matplotlib¶

Here is an example of a simple random-walk plot in Matplotlib, using its classic plot formatting and colors. We start with the typical imports:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.style.use('classic')

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

Now we create some random walk data:

# Create some data

rng = np.random.RandomState(0)

x = np.linspace(0, 10, 500)

y = np.cumsum(rng.randn(500, 6), 0)

And do a simple plot:

# Plot the data with Matplotlib defaults

plt.plot(x, y)

plt.legend('ABCDEF', ncol=2, loc='upper left');

Although the result contains all the information we'd like it to convey, it does so in a way that is not all that aesthetically pleasing, and even looks a bit old-fashioned in the context of 21st-century data visualization.

Now let's take a look at how it works with Seaborn.

As we will see, Seaborn has many of its own high-level plotting routines, but it can also overwrite Matplotlib's default parameters and in turn get even simple Matplotlib scripts to produce vastly superior output.

We can set the style by calling Seaborn's set() method.

By convention, Seaborn is imported as sns:

import seaborn as sns

sns.set()

Now let's rerun the same two lines as before:

# same plotting code as above!

plt.plot(x, y)

plt.legend('ABCDEF', ncol=2, loc='upper left');

Exploring Seaborn Plots¶

The main idea of Seaborn is that it provides high-level commands to create a variety of plot types useful for statistical data exploration, and even some statistical model fitting.

Let's take a look at a few of the datasets and plot types available in Seaborn. Note that all of the following could be done using raw Matplotlib commands (this is, in fact, what Seaborn does under the hood) but the Seaborn API is much more convenient.

Histograms, KDE, and densities¶

Often in statistical data visualization, all you want is to plot histograms and joint distributions of variables. We have seen that this is relatively straightforward in Matplotlib:

data = np.random.multivariate_normal([0, 0], [[5, 2], [2, 2]], size=2000)

data = pd.DataFrame(data, columns=['x', 'y'])

for col in 'xy':

plt.hist(data[col], normed=True, alpha=0.5)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- AttributeError Traceback (most recent call last) <ipython-input-64-7c25cafad82f> in <module>() 3 4 for col in 'xy': ----> 5 plt.hist(data[col], normed=True, alpha=0.5) /usr/local/lib/python3.7/dist-packages/matplotlib/pyplot.py in hist(x, bins, range, density, weights, cumulative, bottom, histtype, align, orientation, rwidth, log, color, label, stacked, data, **kwargs) 2608 align=align, orientation=orientation, rwidth=rwidth, log=log, 2609 color=color, label=label, stacked=stacked, **({"data": data} -> 2610 if data is not None else {}), **kwargs) 2611 2612 /usr/local/lib/python3.7/dist-packages/matplotlib/__init__.py in inner(ax, data, *args, **kwargs) 1563 def inner(ax, *args, data=None, **kwargs): 1564 if data is None: -> 1565 return func(ax, *map(sanitize_sequence, args), **kwargs) 1566 1567 bound = new_sig.bind(ax, *args, **kwargs) /usr/local/lib/python3.7/dist-packages/matplotlib/axes/_axes.py in hist(self, x, bins, range, density, weights, cumulative, bottom, histtype, align, orientation, rwidth, log, color, label, stacked, **kwargs) 6817 if patch: 6818 p = patch[0] -> 6819 p.update(kwargs) 6820 if lbl is not None: 6821 p.set_label(lbl) /usr/local/lib/python3.7/dist-packages/matplotlib/artist.py in update(self, props) 1004 1005 with cbook._setattr_cm(self, eventson=False): -> 1006 ret = [_update_property(self, k, v) for k, v in props.items()] 1007 1008 if len(ret): /usr/local/lib/python3.7/dist-packages/matplotlib/artist.py in <listcomp>(.0) 1004 1005 with cbook._setattr_cm(self, eventson=False): -> 1006 ret = [_update_property(self, k, v) for k, v in props.items()] 1007 1008 if len(ret): /usr/local/lib/python3.7/dist-packages/matplotlib/artist.py in _update_property(self, k, v) 1000 if not callable(func): 1001 raise AttributeError('{!r} object has no property {!r}' -> 1002 .format(type(self).__name__, k)) 1003 return func(v) 1004 AttributeError: 'Rectangle' object has no property 'normed'

Rather than a histogram, we can get a smooth estimate of the distribution using a kernel density estimation, which Seaborn does with sns.kdeplot:

for col in 'xy':

sns.kdeplot(data[col], shade=True)

Histograms and KDE can be combined using distplot:

sns.distplot(data['x'])

sns.distplot(data['y']);

If we pass the full two-dimensional dataset to kdeplot, we will get a two-dimensional visualization of the data:

sns.kdeplot(data);

We can see the joint distribution and the marginal distributions together using sns.jointplot.

For this plot, we'll set the style to a white background:

with sns.axes_style('white'):

sns.jointplot("x", "y", data, kind='kde');

There are other parameters that can be passed to jointplot—for example, we can use a hexagonally based histogram instead:

with sns.axes_style('white'):

sns.jointplot("x", "y", data, kind='hex')

Pair plots¶

When you generalize joint plots to datasets of larger dimensions, you end up with pair plots. This is very useful for exploring correlations between multidimensional data, when you'd like to plot all pairs of values against each other.

We'll demo this with the well-known Iris dataset, which lists measurements of petals and sepals of three iris species:

iris = sns.load_dataset("iris")

iris.head()

Visualizing the multidimensional relationships among the samples is as easy as calling sns.pairplot:

sns.pairplot(iris, hue='species', size=2.5);

Plotly¶

Plotly Python is an open-source library built on top of plotly.js which allows users to create professional quality, interactive, web-based or standalone visualizations or applications.

Visualizations can be displayed in Jupyter notebooks, standalone HTML files, or integrated into web-applications via the Dash framework.

Over 40 unique charts and limitless customization options exist across statistical, financial, geographic, scientific, and 3-D plot types. (from plotly website)

There are a couple more notes in regards to Plotly that is needed to be shared:

Plotly - Online

Plotly - Enterprise

Intro to Model Building and inference frameworks¶

scikit-learn¶

Reference: Scientific Python Stanford University

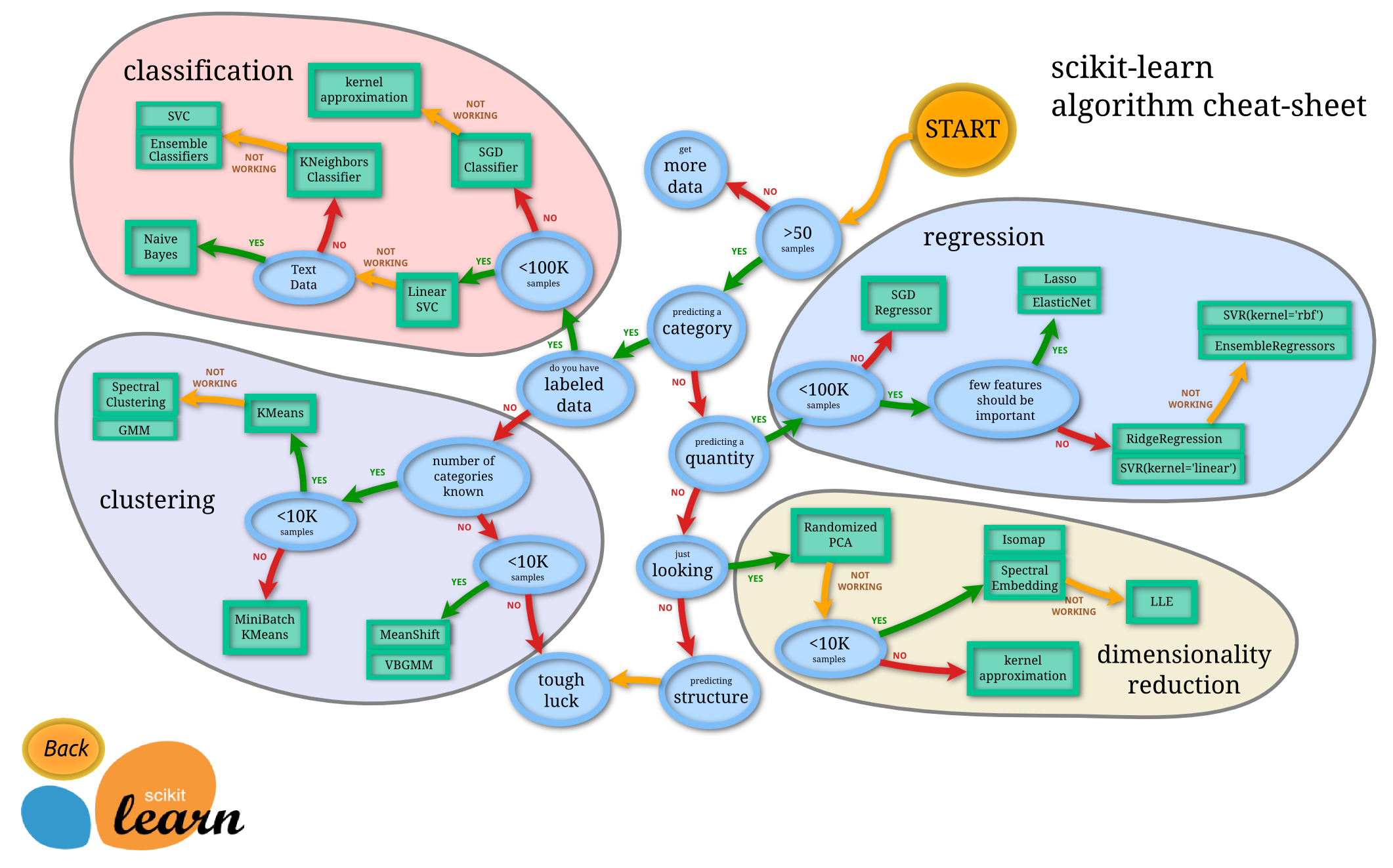

Scikit-learn is a library that allows you to do machine learning, that is, make predictions from data, in Python. There are four basic machine learning tasks:

- Regression: predict a number from datapoints, given datapoints and corresponding numbers

- Classification: predict a category from datapoints, given datapoints and corresponding numbers

- Clustering: predict a category from datapoints, given only datapoints

- Dimensionality reduction: make datapoints lower-dimensional so that we can visualize the data

Here is a handy flowchart of when to use each technique.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Regression¶

Abalone are a type of edible marine snail, and they have internal rings that correspond to their age (like trees). In the following, we will use a dataset of abalone measurements. It has the following fields:

Sex / nominal / -- / M, F, and I (infant)

Length / continuous / mm / Longest shell measurement

Diameter / continuous / mm / perpendicular to length

Height / continuous / mm / with meat in shell

Whole weight / continuous / grams / whole abalone

Shucked weight / continuous / grams / weight of meat

Viscera weight / continuous / grams / gut weight (after bleeding)

Shell weight / continuous / grams / after being dried

Rings / integer / -- / +1.5 gives the age in years Suppose we are interested in predicting the age of the abalone given their measurements. This is an example of a regression problem.

df = pd.read_csv('http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/machine-learning-databases/abalone/abalone.data',

header=None, names=['sex', 'length', 'diameter', 'height', 'weight', 'shucked_weight',

'viscera_weight', 'shell_weight', 'rings'])

df.head()

df.describe()

df['rings'].plot(kind='hist')

df.plot('weight', 'rings', kind='scatter')

X = df[['weight']].to_numpy()

y = df['rings'].to_numpy()

X

y

from sklearn import linear_model

model = linear_model.LinearRegression()

model.fit(X, y)

print(model.coef_, model.intercept_)

print(model.score(X, y))

model.predict(np.array([[1.5], [2.2]]))

df.plot('weight', 'rings', kind='scatter')

weight = np.linspace(0, 3, 10).reshape(-1, 1)

plt.plot(weight, model.predict(weight), 'r')

df['root_weight'] = np.sqrt(df['weight'])

X = df[['weight','root_weight']].to_numpy()

y = df['rings'].to_numpy()

model = linear_model.LinearRegression()

model.fit(X, y)

weight = np.linspace(0, 3, 100).reshape(-1, 1)

root_weight = np.sqrt(weight)

features = np.hstack((weight,root_weight))

df.plot('weight', 'rings', kind='scatter')

plt.plot(weight, model.predict(features), 'r')

model.score(X,y)

plt.hist2d(df['weight'],df['rings'],bins=(50,30));

Classification¶

Another example of a machine learning problem is classification. Here we will use a dataset of flower measurements from three different flower species of Iris (Iris setosa, Iris virginica, and Iris versicolor). We aim to predict the species of the flower. Because the species is not a numerical output, it is not a regression problem, but a classification problem.

from sklearn import datasets

iris = datasets.load_iris()

print(iris.DESCR)

X = iris.data[:, 2:]

y = iris.target_names[iris.target]

for name in iris.target_names:

plt.scatter(X[y == name, 0], X[y == name, 1], label=name)

plt.xlabel('Petal length')

plt.ylabel('Petal width')

plt.legend();

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=0)

print(X_train.shape, y_train.shape)

print(X_test.shape, y_test.shape)

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

model = KNeighborsClassifier()

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

X_test

model.predict(X_test)

import sklearn.metrics as metrics

metrics.accuracy_score(model.predict(X_test), y_test)

print(metrics.classification_report(model.predict(X_test), y_test))

Clustering¶

Clustering is useful if we don't have a dataset labelled with the categories we want to predict, but we nevertheless expect there to be a certain number of categories. For example, suppose we have the previous dataset, but we are missing the labels. We can use a clustering algorithm like k-means to cluster the datapoints. Because we don't have labels, clustering is what is called an unsupervised learning algorithm.

from sklearn.datasets import make_blobs

X,y = make_blobs(centers=4, n_samples=200, random_state=0, cluster_std=0.7)

print(X[:10],y[:10])

Now we plot these points, but without coloring the points using the labels:

plt.scatter(X[:,0],X[:,1]);

We can still discern four clusters in the data set. Let's see if the k-means algorithm can recover these clusters. First we create the instance of the k-means model by giving it the number of clusters 4 as a hyperparameter.

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

model = KMeans(4)

model.fit(X)

print(model.cluster_centers_)

plt.scatter(X[:,0],X[:,1], c=model.labels_);

plt.scatter(model.cluster_centers_[:,0], model.cluster_centers_[:,1], s=100, color="red"); # Show the centres

Dimensionality reduction¶

Dimensionality reduction is another unsupervised learning problem (that is, it does not require labels). It aims to project datapoints into a lower dimensional space while preserving distances between datapoints.

Tensorflow

Tensorflow

TensorFlow is an end-to-end open source platform for machine learning.

TensorFlow was originally created by Google as an internal machine learning tool, but an implementation of it was open sourced under the Apache 2.0 License in November 2015.

Few reason for the popluarity of tensorflow

- Python API

- Portability: deploy computation to one or more CPUs or GPUs in a esktop, server, or mobile device with a single API

- Flexibility: from Raspberry Pi, Android, Windows, iOS, Linux to server farms

- Visualization

- Checkpoints (for managing experiments)

- Large community (> 10,000 commits and > 3000 TF-related repos in one year)

- Awesome projects already using TensorFlow

Reference: Tensorflow beginner

import tensorflow as tf

Load and prepare the MNIST dataset. Convert the samples from integers to floating-point numbers:

mnist = tf.keras.datasets.mnist

(x_train, y_train), (x_test, y_test) = mnist.load_data()

x_train, x_test = x_train / 255.0, x_test / 255.0

Build the tf.keras.Sequential model by stacking layers. Choose an optimizer and loss function for training:

model = tf.keras.models.Sequential([

tf.keras.layers.Flatten(input_shape=(28, 28)),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(128, activation='relu'),

tf.keras.layers.Dropout(0.2),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(10)

])

model.compile(optimizer='adam',

loss='sparse_categorical_crossentropy',

metrics=['accuracy'])

The Model.fit method adjusts the model parameters to minimize the loss:

model.fit(x_train, y_train, epochs=5)

The Model.evaluate method checks the models performance, usually on a "Validation-set" or "Test-set".

model.evaluate(x_test, y_test, verbose=2)

The image classifier is now trained to ~98% accuracy on this dataset. To learn more, read the TensorFlow tutorials.

Pytorch¶

PyTorch is a machine learning framework that is used in both academia and industry for various applications. An alternative to tensorflow

---¶

3. Approaching a Tabular Problem

Titanic Survivor Prediction Challenge

3.1 Understanding the Problem

This challenge is kind of a "hello world" program in the whole data Science and Machine Learning community.

The task is simple,use machine learning to create a model that predicts which passengers survived the Titanic shipwreck. In this challenge, we perform a basic EDA and build a predictive model that answers the question: “what sorts of people were more likely to survive?” using passenger data (ie name, age, gender, socio-economic class, etc).

While there was some element of luck involved in surviving, it seems some groups of people were more likely to survive than others.

Contents

1. Data Description

2. Exploratory Data Analysis

3. Findings From EDA

4. Data Preprocessing

5. Feature Engineering and Feature Selection

6. Data Modeling and Evaluation

* Logistic Regression

* Gradient Boosting Classifier

* XgBoost

* SGB Classifier

7. Models Comparison

Data Description

- Survival : 0 = No, 1 = Yes

- pclass(Ticket Class) : 1 = 1st, 2 = 2nd, 3 = 3rd

- Sex(Gender) : Male, Female

- Age : Age in years

- SibSp : Number of siblings/spouses abroad the titanic

- Parch : Number of parents/children abrod the titanic

- Ticket : Ticket Number

- Fare : Passenger fare

- Cabin : Cabin Number

- Embarked : Port of Embarkation, C = Cherbourg, Q = Queenstown, S = Southampton

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore')

plt.style.use('fivethirtyeight')

%matplotlib inline

#loading a CSV file using pandas dataframe

train_df = pd.read_csv('./inputs/tab/train.csv')

train_df.head()

#Fetching some statistical information of the data

train_df.describe()

#Information about a DataFrame including the index dtype and columns, non-null values and memory usage

train_df.info()

# Checking for null values

train_df.isna().sum()

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

Exploratory Data Analysis refers to the critical process of performing initial investigations on data so as to discover patterns,to spot anomalies,to test hypothesis and to check assumptions with the help of summary statistics and graphical representations

# visualizing null values

import missingno as msno

msno.bar(train_df)

plt.show()

# Correlation and mulitcolinarity

plt.figure(figsize = (18, 8))

corr = train_df.corr()

sns.heatmap(corr, annot = True, fmt = '.2f', linewidths = 1, annot_kws = {'size' : 15})

plt.show()

Survived Column - Target

plt.figure(figsize = (12, 7))

sns.countplot(y = 'Survived', data = train_df)

plt.show()

#pie chart to show Survived vs Not in percentage

values = train_df['Survived'].value_counts()

labels = ['Not Survived', 'Survived']

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (5, 5), dpi = 100)

explode = (0, 0.06)

patches, texts, autotexts = ax.pie(values, labels = labels, autopct = '%1.2f%%', shadow = True,

startangle = 90, explode = explode)

plt.setp(texts, color = 'grey')

plt.setp(autotexts, size = 12, color = 'white')

autotexts[1].set_color('black')

plt.show()

Pclass Column

#individual count of each class

train_df.Pclass.value_counts()

#Individual counts of Pclass based on Target

train_df.groupby(['Pclass', 'Survived'])['Survived'].count()

#bar chart showing Pclass counts based on Targets

plt.figure(figsize = (16, 8))

sns.countplot('Pclass', hue = 'Survived', data = train_df)

plt.show()

#Pie chart showing Pclass counts percentage based on Targets

values = train_df['Pclass'].value_counts()

labels = ['Third Class', 'Second Class', 'First Class']

explode = (0, 0, 0.08)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (5, 6), dpi = 100)

patches, texts, autotexts = ax.pie(values, labels = labels, autopct = '%1.2f%%', shadow = True,

startangle = 90, explode = explode)

plt.setp(texts, color = 'grey')

plt.setp(autotexts, size = 13, color = 'white')

autotexts[2].set_color('black')

plt.show()

Name Column

#Count of uniqes names

train_df.Name.value_counts()

len(train_df.Name.unique()), train_df.shape

Gender Column

#Count of Male vs Female grouped on Target

train_df.groupby(['Sex', 'Survived'])['Survived'].count()

#Individual counts of Gender based on Target

plt.figure(figsize = (16, 7))

sns.countplot('Sex', hue = 'Survived', data = train_df)

plt.show()

#Individual counts of Gender based on Target for each Pclass Category

sns.catplot(x = 'Sex', y = 'Survived', data = train_df, kind = 'bar', col = 'Pclass')

plt.show()

Age Column

#Age distribution

plt.figure(figsize = (15, 6))

plt.style.use('ggplot')

sns.distplot(train_df['Age'])

plt.show()

#Checking outliers in Age grouped by Gender

sns.catplot(x = 'Sex', y = 'Age', kind = 'box', data = train_df, height = 5, aspect = 2)

plt.show()

#Checking outliers in Age grouped by Gender and Pclass

sns.catplot(x = 'Sex', y = 'Age', kind = 'box', data = train_df, col = 'Pclass')

plt.show()

Cabin Column

Fare Column

#Histogram showing Fare counts

plt.figure(figsize = (14, 6))

plt.hist(train_df.Fare, bins = 60, color = 'orange')

plt.xlabel('Fare')

plt.show()

#outliers in Fare based on Gender and Pclass

sns.catplot(x = 'Sex', y = 'Fare', data = train_df, kind = 'box', col = 'Pclass')

plt.show()

SibSp Column

#Count of people with Siblings or spouse

train_df['SibSp'].value_counts()

#count of people with Sibilings or Spouse based on Target

plt.figure(figsize = (16, 5))

sns.countplot(x = 'SibSp', data = train_df, hue = 'Survived')

plt.show()

#Count of people who survived based on SibSp counts

sns.catplot(x = 'SibSp', y = 'Survived', kind = 'bar', data = train_df, height = 5, aspect =2)

plt.show()

#Count of people who survived based on SibSp counts Gender wise

sns.catplot(x = 'SibSp', y = 'Survived', kind = 'bar', hue = 'Sex', data = train_df, height = 6, aspect = 2)

plt.show()

sns.catplot(x = 'SibSp', y = 'Survived', kind = 'bar', col = 'Sex', data = train_df)

plt.show()

#Count of people who survived based on SibSp counts Gender and Pclass wise

sns.catplot(x = 'SibSp', y = 'Survived', col = 'Pclass', kind = 'bar', data = train_df)

plt.show()

Parch Column

#Count of people with Parents/Childrens

train_df.Parch.value_counts()

sns.catplot(x = 'Parch', y = 'Survived', data = train_df, hue = 'Sex', kind = 'bar', height = 6, aspect = 2)

plt.show()

Ticket Column

#count based on ticket types

train_df.Ticket.value_counts()

len(train_df.Ticket.unique())

Embarked Column

train_df['Embarked'].value_counts()

#Count of people based on Port Embarked Gender wise

plt.figure(figsize = (14, 6))

sns.countplot('Embarked', hue = 'Survived', data = train_df)

plt.show()

sns.catplot(x = 'Embarked', y = 'Survived', kind = 'bar', data = train_df, col = 'Sex')

plt.show()

Findings From EDA :-

- Females Survived more than Males.

- Passengers Travelling in Higher Class Survived More than Passengers travelling in Lower Class.

- Name column is having all unique values so this column is not suitable for prediction, we have to drop it.

- In First Class Females were more than Males, that's why Fare of Females Passengers were high.

- Survival Rate is higher for those who were travelling with siblings or spouses.

- Passengers travelling with parents or children have higher survival rate.

- Ticket column is not useful and does not have an impact on survival.

- Cabin column have a lot of null values , it will be better to drop this column.

- Passengers travelling from Cherbourg port survived more than passengers travelling from other two ports.

3.2 Data Preprocessing

# dropping useless columns with noise, missing data ..etc

train_df.drop(['PassengerId', 'Name', 'Ticket', 'Cabin'], axis = 1, inplace = True)

train_df.head()

train_df.isna().sum()

# replacing Zero values of "Fare" column with mean of column

train_df['Fare'] = train_df['Fare'].replace(0, train_df['Fare'].mean())

# filling null values of "Age" column with mean value of the column

train_df['Age'].fillna(train_df['Age'].mean(), inplace = True)

# filling null values of "Embarked" column with mode value of the column

train_df['Embarked'].fillna(train_df['Embarked'].mode()[0], inplace = True)

# checking for null values after filling null values

train_df.isna().sum()

train_df.head()

3.4 Feature Engineering and Feature Selection

'''

Not all Machine Leanrning Algorithms like categorical fearures as strings,

so they need to me encoded to numeric formats so they these alorithms can ingest this data without throwing error

labelEncoding : Converting String to numeric format'''

train_df['Sex'] = train_df['Sex'].apply(lambda val: 1 if val == 'male' else 0)

train_df.head()

OneHot Encoding : It is the representation of categorical variables as binary vectors

# Get one hot encoding of columns 'Embarked'

one_hot = pd.get_dummies(train_df['Embarked'])

# Drop column 'Embarked' as it is now encoded

train_df = train_df.drop('Embarked',axis = 1)

# Join the encoded train_df

train_df = train_df.join(one_hot)

train_df.head()

train_df.describe()

#checking for feature variance is very important

#High variance can affect the model performance, espcially for Linear models

#so we need to normalize high variance features

train_df.var()

#log normalization

train_df['Age'] = np.log(train_df['Age'])

train_df['Fare'] = np.log(train_df['Fare'])

test_df = pd.read_csv('./inputs/tab/test.csv')

test_df.head()

# dropping useless columns

test_df.drop(['PassengerId', 'Name', 'Ticket', 'Cabin'], axis = 1, inplace = True)

# replacing Zero values of "Fare" column with mean of column

test_df['Fare'] = test_df['Fare'].replace(0, test_df['Fare'].mean())

# filling null values of "Age" column with mean value of the column

test_df['Age'].fillna(test_df['Age'].mean(), inplace = True)

# filling null values of "Embarked" column with mode value of the column

test_df['Embarked'].fillna(test_df['Embarked'].mode()[0], inplace = True)

test_df.isna().sum()

# filling null values of "Fare" column with mean value of the column

test_df['Fare'].fillna(test_df['Fare'].mean(), inplace = True)

test_df['Sex'] = test_df['Sex'].apply(lambda val: 1 if val == 'male' else 0)

# Get one hot encoding of columns 'Embarked'

one_hot_test = pd.get_dummies(test_df['Embarked'])

# Drop column 'Embarked' as it is now encoded

test_df = test_df.drop('Embarked',axis = 1)

# Join the encoded train_df

test_df = test_df.join(one_hot_test)

# Log Normalization

test_df['Age'] = np.log(test_df['Age'])

test_df['Fare'] = np.log(test_df['Fare'])

test_df.head()

test_df.var()

test_df.isna().any()

test_df.head()

# Dividing data to features and targets

X = train_df.drop('Survived', axis = 1)

y = train_df['Survived']

# splitting data intp training and test set

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 0.30, random_state = 0)

Data Modeling

Training Machine Learning models to predict survivors

1. Logistic Regression

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

lr = LogisticRegression()

lr.fit(X_train, y_train)

# accuracy score, confusion matrix and classification report of logistic regression

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, confusion_matrix, classification_report

lr_acc = accuracy_score(y_test, lr.predict(X_test))

print(f"Training Accuracy of Logistic Regression is {accuracy_score(y_train, lr.predict(X_train))}")

print(f"Test Accuracy of Logistic Regression is {lr_acc}")

print(f"Confusion Matrix :- \n {confusion_matrix(y_test, lr.predict(X_test))}")

print(f"Classofocation Report : -\n {classification_report(y_test, lr.predict(X_test))}")

# hyper parameter tuning of logistic regression

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV

grid_param = {

'penalty': ['l1', 'l2'],

'C' : [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 0.005, 0.5, 1, 10]

}

grid_search_lr = GridSearchCV(lr, grid_param, cv = 5, n_jobs = -1, verbose = 1)

grid_search_lr.fit(X_train, y_train)

# best parameters and best score

print(grid_search_lr.best_params_)

print(grid_search_lr.best_score_)

# best estimator

lr = grid_search_lr.best_estimator_

# accuracy score, confusion matrix and classification report of logistic regression

lr_acc = accuracy_score(y_test, lr.predict(X_test))

print(f"Training Accuracy of Logistic Regression is {accuracy_score(y_train, lr.predict(X_train))}")

print(f"Test Accuracy of Logistic Regression is {lr_acc}")

print(f"Confusion Matrix :- \n {confusion_matrix(y_test, lr.predict(X_test))}")

print(f"Classofocation Report : -\n {classification_report(y_test, lr.predict(X_test))}")

2. Random Forest

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

rd_clf = RandomForestClassifier()

rd_clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

# accuracy score, confusion matrix and classification report of random forest

rd_clf_acc = accuracy_score(y_test, rd_clf.predict(X_test))

print(f"Training Accuracy of Decision Tree Classifier is {accuracy_score(y_train, rd_clf.predict(X_train))}")

print(f"Test Accuracy of Decision Tree Classifier is {rd_clf_acc} \n")

print(f"Confusion Matrix :- \n{confusion_matrix(y_test, rd_clf.predict(X_test))}\n")

print(f"Classification Report :- \n {classification_report(y_test, rd_clf.predict(X_test))}")

3. Gradient Boosting

from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingClassifier

gb = GradientBoostingClassifier()

gb.fit(X_train, y_train)

# accuracy score, confusion matrix and classification report of gradient boosting classifier

gb_acc = accuracy_score(y_test, gb.predict(X_test))

print(f"Training Accuracy of Decision Tree Classifier is {accuracy_score(y_train, gb.predict(X_train))}")

print(f"Test Accuracy of Decision Tree Classifier is {gb_acc} \n")

print(f"Confusion Matrix :- \n{confusion_matrix(y_test, gb.predict(X_test))}\n")

print(f"Classification Report :- \n {classification_report(y_test, gb.predict(X_test))}")

4. Stochastic Gradient Boosting (SGB)

sgb = GradientBoostingClassifier(subsample = 0.90, max_features = 0.70)

sgb.fit(X_train, y_train)

# accuracy score, confusion matrix and classification report of stochastic gradient boosting classifier

sgb_acc = accuracy_score(y_test, sgb.predict(X_test))

print(f"Training Accuracy of Decision Tree Classifier is {accuracy_score(y_train, sgb.predict(X_train))}")

print(f"Test Accuracy of Decision Tree Classifier is {sgb_acc} \n")

print(f"Confusion Matrix :- \n{confusion_matrix(y_test, sgb.predict(X_test))}\n")

print(f"Classification Report :- \n {classification_report(y_test, sgb.predict(X_test))}")

5. XGboost

from xgboost import XGBClassifier

xgb = XGBClassifier(booster = 'gbtree', learning_rate = 0.1, max_depth = 5, n_estimators = 180)

xgb.fit(X_train, y_train)

# accuracy score, confusion matrix and classification report of xgboost

xgb_acc = accuracy_score(y_test, xgb.predict(X_test))

print(f"Training Accuracy of Decision Tree Classifier is {accuracy_score(y_train, xgb.predict(X_train))}")

print(f"Test Accuracy of Decision Tree Classifier is {xgb_acc} \n")

print(f"Confusion Matrix :- \n{confusion_matrix(y_test, xgb.predict(X_test))}\n")

print(f"Classification Report :- \n {classification_report(y_test, xgb.predict(X_test))}")

Model Comparison

models = pd.DataFrame({

'Model' : ['Logistic Regression', 'Gradient Boosting Classifier', 'Stochastic Gradient Boosting', 'XgBoost'],

'Score' : [lr_acc,gb_acc, sgb_acc, xgb_acc]

})

models.sort_values(by = 'Score', ascending = False)

plt.figure(figsize = (15, 10))

sns.barplot(x = 'Score', y = 'Model', data = models)

plt.show()

Real Data Model Inference

pred_class = {0: 'Not Survived', 1: 'Survived'}

def predict(test_input, test_target):

final_results = gb.predict([test_input])

test_input['Age'] = np.exp(test_input['Age'])

test_input['Fare'] = np.exp(test_input['Fare'])

print(f"Features:\n{test_input}\n\nClassifier prediction: {pred_class[final_results.item()]}\nActual Target: {pred_class[test_target]}")

test_input = X.iloc[0,:]

test_target = y.iloc[0]

predict(test_input, test_target)

test_input = X.iloc[1,:]

test_target = y.iloc[1]

predict(test_input, test_target)

4. Approaching a Text (NLP) Problem

4.1 Importance of solving NLP¶

NLP — also known as computational linguistics — is the combination of AI and linguistics that allows us to talk to machines as if they were human.

In other words, NLP is an approach to process, analyze and understand large amount of text data.

1. Handling large volumes of text data¶

With the big data technology, NLP has entered the mainstream as this approach can now be applied to handle large volumes of text data via cloud/distributed computing at an unprecedented speed.

2. Structuring highly unstructured data source¶

Human language is astoundingly complex and diverse.

NLP is important because it helps resolve ambiguity in language and adds useful numeric structure to the data for many downstream applications, such as speech recognition or text analytics.

Components of NLP¶

NLP can be divided into two basic components.

- Natural Language Understanding

- Natural Language Generation

Natural Language Understanding (NLU)¶

There are lot of ambiguity while learning or trying to interpret a language.

- Lexical Ambiguity can occur when a word carries different sense

- Syntactical Ambiguity means when we see more than one meaning in a sequence of words.

- Referential Ambiguity: Very often a text mentions as entity (something/someone),

Natural Language Generation (NLG)¶

It involves :

- Text planning − It includes retrieving the relevant content from knowledge base.

- Sentence planning − It includes choosing required words, forming meaningful phrases, setting tone of the sentence.

- Text Realization − It is mapping sentence plan into sentence structure.

Applications of NLP¶

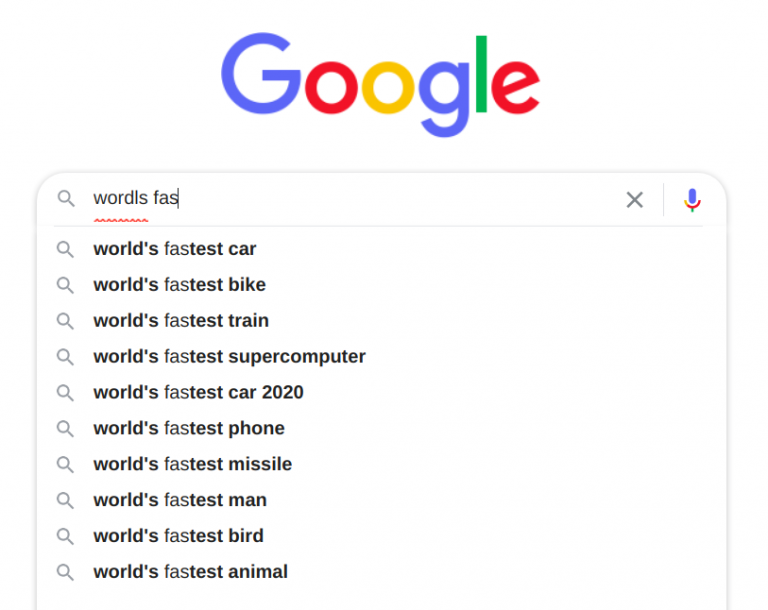

Search Autocorrect and Autocomplete¶

Language Translator¶

Chatbots¶

Sentiment analysis¶

4.3 Basics of NLP

Corpus

A corpus is a large and structured set of machine-readable texts that have been produced in a natural communicative setting. Its plural is corpora. They can be derived in different ways like text that was originally electronic, transcripts of spoken language and optical character recognition, etc.

Tokens

The raw text is a sequence of characters (bytes), but most times it is useful to group those characters into contiguous units called tokens. In English, tokens correspond to words and numeric sequences separated by white-space characters or punctuation.

Tokenization

The process of breaking a text down into tokens is called tokenization.It can become more complicated than simply splitting text based on nonalphanumeric characters.

N-grams

They are basically a set of co-occurring words within a given window and when computing the n-grams you typically move one word forward. Trigram has three token, bigram has two tokens, a unigram one.

Stemming

Stemming algorithms work by cutting off the end or the beginning of the word, taking into account a list of common prefixes and suffixes that can be found in an inflected word.Stemming just removes the last few characters, often leading to incorrect meanings and spelling errors

Lemmatization

Lemmatization is similar to stemming but it brings context to the words. So it links words with similar meaning to one word.

4.4 NLP using Python

NLTK

It is a leading platform for building Python programs to work with human language data. It provides easy-to-use interfaces to over 50 corpora and lexical resources such as WordNet, along with a suite of text processing libraries for classification, tokenization, stemming, tagging, parsing, and semantic reasoning, wrappers for industrial-strength NLP libraries

spaCy

It is an open-source software library for advanced natural language processing, written in the programming languages Python and Cython.Unlike NLTK, which is widely used for teaching and research, spaCy focuses on providing software for production usage.spaCy also supports deep learning workflows that allow connecting statistical models trained by popular machine learning libraries like TensorFlow, PyTorch or MXNet through its own machine learning library Thinc

4.5 Approaching real life NLP problem

Intro to Twitter tweets processing using Python

Problem Statement

With all of the tweets circulating every second it is hard to tell whether the sentiment behind a specific tweet will impact a company, or a person's, brand for being viral (positive), or devastate profit because it strikes a negative tone. Capturing sentiment in language is important in these times where decisions and reactions are created and updated in seconds. In order to get the sentiments out of tweets they need to by processed to tweaked in ways so that it could be fed into a algorithm to perform to sentiment inference. So we will take a look at pythonic approach of processing tweets

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import numpy as np

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

from nltk.util import ngrams

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer

from wordcloud import WordCloud, STOPWORDS

from nltk.stem.wordnet import WordNetLemmatizer

from nltk import word_tokenize

from collections import defaultdict

from collections import Counter

plt.style.use('ggplot')

stop=set(stopwords.words('english'))

import re

from nltk.tokenize import word_tokenize

import gensim

import string

from tqdm import tqdm

tweet=pd.read_csv("./inputs/nlp/train.csv")

test=pd.read_csv("./inputs/nlp/test.csv")

tweet.head(100)

print('There are {} rows and {} columns in train'.format(tweet.shape[0],tweet.shape[1]))

print('There are {} rows and {} columns in train'.format(test.shape[0],test.shape[1]))

Class Distribution

Before we begin with anything else,let's check the class distribution.There are only two classes 0 and 1.

x=tweet.target.value_counts()

sns.barplot(x.index,x)

plt.gca().set_ylabel('samples')

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

#First,we will do very basic analysis,that is character level,word level and sentence level analysis.

fig,(ax1,ax2)=plt.subplots(1,2,figsize=(10,5))

tweet_len=tweet[tweet['target']==1]['text'].str.len()

ax1.hist(tweet_len,color='red')

ax1.set_title('disaster tweets')

tweet_len=tweet[tweet['target']==0]['text'].str.len()

ax2.hist(tweet_len,color='green')

ax2.set_title('Not disaster tweets')

fig.suptitle('Characters in tweets')

plt.show()

print("The distribution of both seems to be almost same.120 t0 140 characters in a tweet are the most common among both.")

# Number of words in tweet

fig,(ax1,ax2)=plt.subplots(1,2,figsize=(10,5))

tweet_len=tweet[tweet['target']==1]['text'].str.split().map(lambda x: len(x))

ax1.hist(tweet_len,color='red')

ax1.set_title('disaster tweets')

tweet_len=tweet[tweet['target']==0]['text'].str.split().map(lambda x: len(x))

ax2.hist(tweet_len,color='green')

ax2.set_title('Not disaster tweets')

fig.suptitle('Words in a tweet')

plt.show()

print("Most of disaster tweets are around between 10 -20 word counts\nand Non disaster tweet areound 15 to 20")

# Average word length in a tweet

fig,(ax1,ax2)=plt.subplots(1,2,figsize=(10,5))

word=tweet[tweet['target']==1]['text'].str.split().apply(lambda x : [len(i) for i in x])

sns.distplot(word.map(lambda x: np.mean(x)),ax=ax1,color='red')

ax1.set_title('disaster')

word=tweet[tweet['target']==0]['text'].str.split().apply(lambda x : [len(i) for i in x])

sns.distplot(word.map(lambda x: np.mean(x)),ax=ax2,color='green')

ax2.set_title('Not disaster')

fig.suptitle('Average word length in each tweet')

Creating Corpus

We need to perform further EDA we need corpus

#creating text corpus based on target

#corpus of Disaster vs Non Disaster Tweet

def build_corpus(target):

corpus=[]

for x in tweet[tweet['target']==target]['text'].str.split():

for i in x:

corpus.append(i)

return corpus

#wordcloud of non disaster tweets

comment_words = ''

stopwords = set(STOPWORDS)

comment_words += " ".join(build_corpus(0))+" "

wordcloud = WordCloud(width = 800, height = 800,

background_color ='white',

stopwords = stopwords,

min_font_size = 10).generate(comment_words)

plt.figure(figsize = (8, 8), facecolor = None)

plt.imshow(wordcloud)

plt.axis("off")

plt.tight_layout(pad = 0)

plt.show()

#wordcloud of disaster tweets

comment_words = ''

stopwords = set(STOPWORDS)

comment_words += " ".join(build_corpus(1))+" "

wordcloud = WordCloud(width = 800, height = 800,

background_color ='black',

stopwords = stopwords,

min_font_size = 10).generate(comment_words)

plt.figure(figsize = (8, 8), facecolor = None)

plt.imshow(wordcloud)

plt.axis("off")

plt.tight_layout(pad = 0)

plt.show()

#creating corpus based of Non Disaster Tweet

corpus=build_corpus(0)

#build dicr based on NoN disaster tweet

dic=defaultdict(int)

for word in corpus:

if word in stop:

dic[word]+=1

#choosing top tweets

top=sorted(dic.items(), key=lambda x:x[1],reverse=True)[:10]

top

#bar chart showing common words in NoN disaster tweets

x,y = zip(*top)

plt.figure(figsize=(15,8))

plt.bar(x, y);

#creating the same for Diaster Tweet

corpus=build_corpus(1)

dic=defaultdict(int)

for word in corpus:

if word in stop:

dic[word]+=1

top=sorted(dic.items(), key=lambda x:x[1],reverse=True)[:10]

plt.figure(figsize=(15,8))

x,y=zip(*top)

plt.bar(x,y)

plt.show()

print("Words like 'the','in','of' dominates, but these words have not much meaning or prediction capabilities")

#Analysing punctuations for Disaster Tweets

plt.figure(figsize=(15,8))

corpus=build_corpus(1)

dic=defaultdict(int)

import string

special = string.punctuation

for i in (corpus):

if i in special:

dic[i]+=1

x,y=zip(*dic.items())

plt.title("Analysing punctuations for Disaster Tweets")

plt.bar(x,y,color='orange');

#Analysing punctuations for Non-Disaster Tweets

plt.figure(figsize=(15,8))

corpus=build_corpus(0)

dic=defaultdict(int)

import string

special = string.punctuation

for i in (corpus):

if i in special:

dic[i]+=1

x,y=zip(*dic.items())

plt.title("Analysing punctuations for Non-Disaster Tweets")

plt.bar(x,y,color='red');

#performing the same for complete corpus

complete_corpus = []

complete_corpus.extend(build_corpus(0))

complete_corpus.extend(build_corpus(1))

counter=Counter(corpus)

most=counter.most_common()

x=[]

y=[]

for word,count in most[:40]:

if (word not in stop) :

x.append(word)

y.append(count)

plt.figure(figsize=(15,8))

sns.barplot(x=y,y=x).set_title("Complete corpus common words")

plt.show()

N-gram Analysis

We can perform Bigram and Trigram analysis on this data to understand word combinations in the dataset

def get_top_tweet_bigrams(corpus, gram=2, n=None):

vec = CountVectorizer(ngram_range=(gram, gram)).fit(corpus)

bag_of_words = vec.transform(corpus)

sum_words = bag_of_words.sum(axis=0)

words_freq = [(word, sum_words[0, idx]) for word, idx in vec.vocabulary_.items()]

words_freq =sorted(words_freq, key = lambda x: x[1], reverse=True)

return words_freq[:n]

#count of common bigrams

plt.figure(figsize=(15,8))

top_tweet_bigrams=get_top_tweet_bigrams(tweet['text'], gram=2)[:10]

x,y=map(list,zip(*top_tweet_bigrams))

sns.barplot(x=y,y=x).set_title("Common Bigram Count")

plt.show()

#count of common trigrams

plt.figure(figsize=(15,8))

top_tweet_trigrams=get_top_tweet_bigrams(tweet['text'], gram=3)[:10]

x,y=map(list,zip(*top_tweet_trigrams))

sns.barplot(x=y,y=x).set_title("Common Trigram Count")

plt.show()

After performing Bigram and Trigram analysis on this data clearly shows the need of data cleaning

Data Cleaning

Raw twitter data contains a lot of noise like stopwords, irrelavant punctuations, emojis ..etc which could kill its prediction capabilities. So let's clean them

df=pd.concat([tweet,test])

df.shape

Lemmatization

def lemma(text):

text = text.lower()

lmtzr = WordNetLemmatizer()

text = " ".join([lmtzr.lemmatize(word) for word in word_tokenize(text)])

return text

ex = "Our Deeds are the Reason of this #earthquake"

lemma(ex)

#apply lemmatization

df['text']=df['text'].apply(lambda x : lemma(x))

Removing URL

#Regex to remove URL

def remove_URL(text):

url = re.compile(r'https?://\S+|www\.\S+')

return url.sub(r'',text)

sample_URL = "please find the titanic project at https://www.kaggle.com/c/titanic/overview"

remove_URL(sample_URL)

#Apply the cleaning process

df['text']=df['text'].apply(lambda x : remove_URL(x))

df[['text','target']].head()

Removing HTML

#remove html

def remove_html(text):

html=re.compile(r'<.*?>')

return html.sub(r'',text)

sample_HTML = '''

<html>

<div>

<h1>Welcome to HTML</h>

<a href="https://www.kaggle.com/c/titanic/overview">kaggle</a>

<p>test paragraph</p>

</div>

</html>

'''

print(remove_html(sample_HTML))

df['text']=df['text'].apply(lambda x : remove_html(x))

df[['text','target']].head()

Removing Emojis 😔

Emoji's have great prediction capabilities but they need to be encoded to some numeric problem, Lets just remove it for simplicity sake

def remove_emoji(text):

emoji_pattern = re.compile("["

u"\U0001F600-\U0001F64F" # emoticons

u"\U0001F300-\U0001F5FF" # symbols & pictographs

u"\U0001F680-\U0001F6FF" # transport & map symbols

u"\U0001F1E0-\U0001F1FF" # flags (iOS)

u"\U00002702-\U000027B0"

u"\U000024C2-\U0001F251"

"]+", flags=re.UNICODE)

return emoji_pattern.sub(r'', text)

remove_emoji("its flooding i am scared 😔😔")

df['text']=df['text'].apply(lambda x: remove_emoji(x))

df[['text','target']].head()

Removing punctuations

Just like emojis punctuation also posses some kind of meaning like :) :( ..etc , But its hard to encode such punctation to numeric formats when vectorizing text. So we can remove it