Archive

Predicted impact of LLM use on developer ecosystems

LLMs are not going to replace developers. Next token prediction is not the path to human intelligence. LLMs provide a convenient excuse for companies not hiring or laying off developers to say that the decision is driven by LLMs, rather than admit that their business is not doing so well

Once the hype has evaporated, what impact will LLMs have on software ecosystems?

The size and complexity of software systems is limited by the human cognitive resources available for its production. LLMs provide a means to reduce the human cognitive effort needed to produce a given amount of software.

Using LLMs enables more software to be created within a given budget, or the same amount of software created with a smaller budget (either through the use of cheaper, and presumably less capable, developers, or consuming less time of more capable developers).

Given the extent to which companies compete by adding more features to their applications, I expect the common case to be that applications contain more software and budgets remain unchanged. In a Red Queen market, companies want to be perceived as supporting the latest thing, and the marketing department needs something to talk about.

Reducing the effort needed to create new features means a reduction in the delay between a company introducing a new feature that becomes popular, and the competition copying it.

LLMs will enable software systems to be created that would not have been created without them, because of timescales, funding, or lack of developer expertise.

I think that LLMs will have a large impact on the use of programming languages.

The quantity of training data (e.g., source code) has an impact on the quality of LLM output. The less widely used languages will have less training data. The table below lists the gigabytes of source code in 30 languages contained in various LLM training datasets (for details see The Stack: 3 TB of permissively licensed source code by Kocetkov et al.):

Language TheStack CodeParrot AlphaCode CodeGen PolyCoder HTML 746.33 118.12 JavaScript 486.2 87.82 88 24.7 22 Java 271.43 107.7 113.8 120.3 41 C 222.88 183.83 48.9 55 C++ 192.84 87.73 290.5 69.9 52 Python 190.73 52.03 54.3 55.9 16 PHP 183.19 61.41 64 13 Markdown 164.61 23.09 CSS 145.33 22.67 TypeScript 131.46 24.59 24.9 9.2 C# 128.37 36.83 38.4 21 GO 118.37 19.28 19.8 21.4 15 Rust 40.35 2.68 2.8 3.5 Ruby 23.82 10.95 11.6 4.1 SQL 18.15 5.67 Scala 14.87 3.87 4.1 1.8 Shell 8.69 3.01 Haskell 6.95 1.85 Lua 6.58 2.81 2.9 Perl 5.5 4.7 Makefile 5.09 2.92 TeX 4.65 2.15 PowerShell 3.37 0.69 FORTRAN 3.1 1.62 Julia 3.09 0.29 VisualBasic 2.73 1.91 Assembly 2.36 0.78 CMake 1.96 0.54 Dockerfile 1.95 0.71 Batchfile 1 0.7 Total 3135.95 872.95 715.1 314.1 253.6 |

The major companies building LLMs probably have a lot more source code (as of July 2023, the Software Heritage had over  unique source code files); this table gives some idea of the relative quantities available for different languages, subject to recency bias. At the moment, companies appear to be training using everything they can get their hands on. Would LLM performance on the widely used languages improve if source code for most of the 682 languages listed on Wikipedia was not included in their training data?

unique source code files); this table gives some idea of the relative quantities available for different languages, subject to recency bias. At the moment, companies appear to be training using everything they can get their hands on. Would LLM performance on the widely used languages improve if source code for most of the 682 languages listed on Wikipedia was not included in their training data?

Traditionally, developers have had to spend a lot of time learning the technical details about how language constructs interact. For the first few languages, acquiring fluency usually takes several years.

It’s possible that LLMs will remove the need for developers to know much about the details of the language they are using, e.g., they will define variables to have the appropriate type and suggest possible options when type mismatches occur.

Removing the fluff of software development (i.e., writing the code) means that developers can invest more cognitive resources in understanding what functionality is required, and making sure that all the details are handled.

Removing a lot of the sunk cost of language learning removes the only moat that some developers have. Job adverts could stop requiring skills with particular programming languages.

Little is currently known about developer career progression, which means it’s not possible to say anything about how it might change.

Since they were first created, programming languages have fascinated developers. They are the fashion icon of software development, with youngsters wanting to program in the latest language, or at least not use the languages used by their parents. If developers don’t invest in learning language details, they have nothing language related to discuss with other developers. Programming languages will cease to be a fashion icon (cpus used to be a fashion icon, until developers did not need to know details about them, such as available registers and unique instructions). Zig could be the last language to become fashionable.

I don’t expect the usage of existing language features to change. LLMs mimic the characteristics of the code they were trained on.

When new constructs are added to a popular language, it can take years before they start to be widely used by developers. LLMs will not use language constructs that don’t appear in their training data, and if developers are relying on LLMs to select the appropriate language construct, then new language constructs will never get used.

By 2035 things should have had time to settle down and for the new patterns of developer behavior to be apparent.

Long term growth of programming language use

The names of files containing source code often include a suffix denoting the programming language used, e.g., .c for C source code. These suffixes provide a cheap and cheerful method for estimating programming language use within a file system directory.

This method has its flaws, with two main factors introducing uncertainty into the results:

- The suffix denoting something other than the designated programming language.

- Developer choice of suffix can change over time and across development environments, e.g., widely used Fortran suffixes include

.f,.for,.ftn, and .f77(Fortran77 was the second revision of the ANSI, and the version I used intensely for several years; ChatGPT only lists later versions, i.e.,f90,f95, etc).

The paper: 50 Years of Programming Language Evolution through the Software Heritage looking glass by A. Desmazières, R. Di Cosmo, and V. Lorentz uses filename suffixes to track the use of programming languages over time. The suffix data comes from the Software Heritage, which aims to collect, and share all publicly available source code, and it currently hosts over 20 billion unique source files.

The authors extract and count all filename suffixes from the Software Heritage archive, obtaining 2,836,119 unique suffixes. GitHub’s linguist catalogue of file extensions was used to identify programming languages. The top 10 most used programming languages, since 2000, are found and various quantities plotted.

A 1976 report found that at least 450 programming languages were in use at the US Department of Defense, and as of 2020 close to 9,000 languages are listed on hopl.info. The linguist catalogue contains information on 512 programming languages, with a strong bias towards languages to write open source. It is missing entries for Cobol and Ada, and its Fortran suffix list does not include .for, .ftn and .f77.

The following analysis takes an all encompassing approach. All suffixes containing at up to three characters, the first of which is alphabetic, and occurring at least 1,000 times in any year, are initially assumed to denote a programming language; the suffixes .html, .java and .json are special cased (4,050 suffixes). This initial list is filtered to remove known binary file formats, e.g., .zip and .jar. The common file extensions listed on FileInfo were filtered using the algorithm applied to the Software Heritage suffixes, producing 3,990 suffixes (the .ftn suffix, and a few others, were manually spotted and removed). Removing binary suffixes reduced the number of assumed language suffixes from 4,050 (15,658,087,071 files) to 2,242 (9,761,794,979 files).

This approach is overly generous, and includes suffixes that have not been used to denote programming language source code.

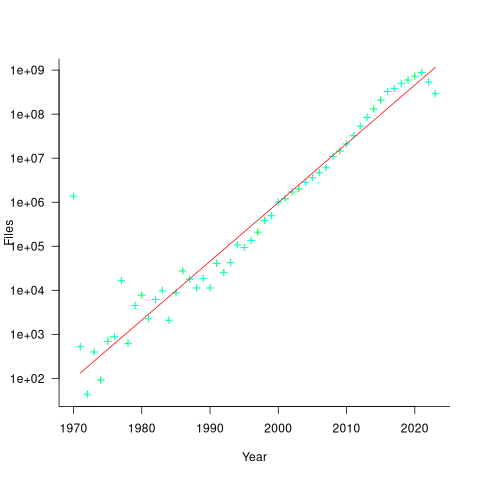

The plot below shows the number of assumed source code files created in each year (only 50% of files have a creation date), with a fitted regression line showing a 31% annual growth in files over 52 years (code+data):

Some of the apparent growth is actually the result of older source being more likely to be lost.

Unix timestamps start on 1 Jan 1970. Most of the 1,411,277 files with a 1970 creation date probably acquired this date because of a broken conversion between version control systems.

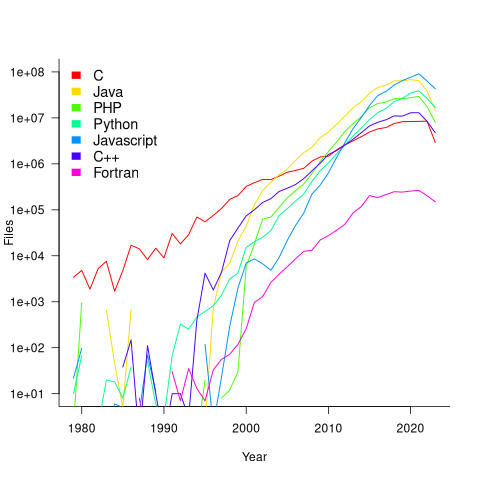

The plot below shows the number of files assumed to contain source code in a given language per year, with some suffixes used before the language was invented (its starts in 1979, when total file counts stat always being over 1,000; code+data):

Over the last few years, survey results have been interpreted as showing declining use of C. This plot suggests that use of C is continuing to grow at around historical rates, but that use of other languages has grown rapidly to claim a greater percentage of developer implementation effort.

The major issue with this plot is what is not there. Where is the Cobol, once the most widely used language? Did Fortran only start to be used during the 1990s? Millions of lines of Cobol and Fortran were written between 1960 and 1985, but very little of this code is publicly available.

Discussing new language features is more fun than measuring feature usage in code

How often are the features supported by a programming language used by developers in the code that they write?

This fundamental question is rarely asked, let alone answered (my contribution).

Existing code is what developers spend their time reading, compilers translating to machine code, and LLMs use as training data.

Frequently used language features are of interest to writers of code optimizers, who want to know where to focus their limited resources (at least I did when I was involved in the optimization business; I was always surprised by others working in the field having almost no interest in measuring user’s code), and educators ought to be interested in teaching what students are mostly likely to be using (rather than teaching the features that are fun to talk about).

The unused, or rarely used language features are also of interest. Is the feature rarely used because developers have no use for the feature, or does its semantics prevent it being practically applied, or some other reason?

Language designers write books, papers, and blog posts discussing their envisaged developer usage of each feature, and how their mental model of the language ties everything together to create a unifying whole; measurements of actual source code very rarely get discussed. Two very interesting reads in this genre are Stroustrup’s The Design and Evolution of C++ and Thriving in a Crowded and Changing World: C++ 2006–2020.

Languages with an active user base are often updated to support new features. The ISO C++ committee is aims to release a new standard every three years, Java is now on a six-month release cycle, and Python has an annual release cycle. The primary incentives driving the work needed to create these updates appears to be:

- sales & marketing: saturation exposure to adverts proclaiming modernity has warped developer perception of programming languages, driving young developers to want to be associated with those perceived as modern. Companies need to hire inexperienced developers (who are likely still running on the modernity treadmill), and appearing out of date can discourage developers from applying for a job,

- designer hedonism and fuel for the trainer/consultant gravy train: people create new programming languages because it’s something they enjoy doing; some even leave their jobs to work on their language full-time. New language features provides material to talk about and income opportunities for trainers/consultants.

Note: I’m not saying that adding new features to a language is bad, but that at the moment worthwhile practical use to developers is a marketing claim rather than an evidence-based calculation.

Those proposing new language features can rightly point out that measuring language usage is a complicated process, and that it takes time for new features to diffuse into developers’ repertoire. Also, studying source code measurement data is not something that appeals to many people.

Also, the primary intended audience for some language features is library implementors, e.g., templates.

There have been some studies of language feature usage. Lambda expressions are a popular research subject, having been added as a new feature to many languages, e.g., C++, Java, and Python. A few papers have studied language usage in specific contexts, e.g., C++ new feature usage in KDE.

The number of language features invariably grow and grow. Sometimes notice is given that a feature will be removed from a future reversion of the language. Notice of feature deprecation invariably leads to developer pushback by the subset of the community that relies on that feature (measuring usage would help prevent embarrassing walk backs).

If the majority of newly written code does end up being created by developers prompting LLMs, then new language features are unlikely ever to be used. Without sufficient training data, which comes from developers writing code using the new features, LLMs are unlikely to respond with code containing new features.

I am not expecting the current incentive structure to change.

Quantity of source in a given language

How much source code exists in a particular language?

Traditionally, indicators of the quantity of source in a language is the number of people making a living working on software written in the language. Job adverts are a proxy for the number of people employed to write/support programs implemented in a language (i.e., number of times a language is specified in the text of an advert), another proxy used to be the financial wellbeing of compiler vendors (many years ago, Open source compilers drove most companies out of the business of selling compilers).

Current job adverts are a measure of the code that likely to be worked now and in the near future. While Cobol dominated the job adverts decades ago, it is only occasionally seen today, suggesting that a lot of Cobol source is no longer actively used.

There now exists a huge quantity of Open source, and it has permeated into all the major, and many minor, software ecosystems. As a measure of all existing source code, how representative is Open source?

The Software Heritage’s mission statement “… is to collect, preserve, and share all software that is publicly available in source code form.” With over  files, as of July 2023 it is the largest available collection of Open source, and furthermore the BigCode project has collated this source into 658 constituent languages, known the Stack version 2.

files, as of July 2023 it is the largest available collection of Open source, and furthermore the BigCode project has collated this source into 658 constituent languages, known the Stack version 2.

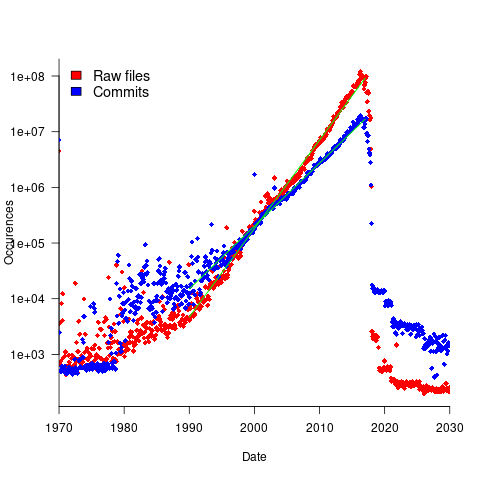

To be representative of all existing source code, the Stack v2 would need to contain a representative sample of source written in all the languages that have been used to implement a non-trivial quantity of code. The plot below shows the number of source files assumed to be from a given year, storage by the Software Heritage; green lines are fitted exponentials (code+data):

Less Open source was written in years gone by because there were fewer developers writing code, and code tends to get lost.

The Wikipedia list of programming languages currently contains links to articles on 682 languages, although some entries do appear to stretch the definition of programming language, e.g., Geometric Description Language. The Stack v2 contains code in 658 languages. However, even the broadest definition of programming language would not include some of the entries, e.g., Vim Help File. There are 176 language names shared between lists (around 27%; code+data).

Wikipedia languages not contained in Stack v2 include dialects of Basic, C, Lisp, Pascal, and shell, along with languages I recognised. Stack v2 languages not contained in the Wikipedia list include a variety of build and configuration files, names I did not recognise and what looked like documentation and data files.

Stack v2 has a broad brush approach to language classification. There is only one Pascal (perhaps the most widely used language in the early days of the IBM PC, Turbo Pascal, does not get a mention, and neither does UCSD Pascal), and assembler languages can vary a lot between cpus (Stack v2 lists: Assembly, Motorola 68K Assembly, Parrot Assembly, WebAssembly, Unix Assembly).

The Online Historical Encyclopaedia of Programming Languages lists information on 8,945 languages. Most of these probably got no further than being implemented in themselves by the language designer (often for a PhD thesis).

The Stack v2’s definition of a non-trivial quantity is at least 1,000 files having a given filename suffix, e.g., .cpp denoting C++ source. I can understand that this limit might exclude some niche languages from long ago (e.g., Coral 66), but why isn’t there any Algol 60 source?

I suspect that many ‘earlier’ languages are not included because the automated source submission process requires that the code be accessible via one of five version control systems. A lot of older source is stored in tar/zip files, accessed via ftp directories or personal web pages. Software Heritage’s Collect and Curate Legacy Code does not yet appear to provide a process for submitting source available in these forms.

While I think that Open source code has the same language usage characteristics as Closed source, I continue to meet people who question this assumption. I doubt that the question will ever get a definitive answer, not least because of an unwillingness to invest the resources needed to do a large sample comparison.

I would expect there to be at least 100 times as much Closed source as Open source, if only because there are a lot more people writing Closed source.

The Whitehouse report on adopting memory safety

Last month’s Whitehouse report: BACK TO THE BUILDING BLOCKS: A Path Towards Secure and Measurable Software “… outlines two fundamental shifts: the need to both rebalance the responsibility to defend cyberspace and realign incentives to favor long-term cybersecurity investments.”

From the abstract: “First, in order to reduce memory safety vulnerabilities at scale, … This report focuses on the programming language as a primary building block, …” Wow, I never expected to see the term ‘memory safety’ in a report from the Whitehouse (not that I recall ever reading a Whitehouse report). And, is this the first Whitehouse report to talk about programming languages?

tl;dr They mistakenly to focus on the tools (i.e., programming languages), the focus needs to be on how the tools are used, e.g., require switching on C compiler’s memory safety checks which currently default to off.

The report’s intent is to get the community to progress from defence (e.g., virus scanning) to offence (e.g., removing the vulnerabilities at source). The three-pronged attack focuses on programming languages, hardware (e.g., CHERI), and formal methods. The report is a rallying call to the troops, who are, I assume, senior executives with no little or no knowledge of writing software.

How did memory safety and programming languages enter the political limelight? What caused the Whitehouse claim that “…, one of the most impactful actions software and hardware manufacturers can take is adopting memory safe programming languages.”?

The cited reference is a report published two months earlier: The Case for Memory Safe Roadmaps: Why Both C-Suite Executives and Technical Experts Need to Take Memory Safe Coding Seriously, published by an alphabet soup of national security agencies.

This report starts by stating the obvious (at least to developers): “Memory safety vulnerabilities are the most prevalent type of disclosed software vulnerability.” (one Microsoft reports says 70%). It then goes on to make the optimistic claim that: “Memory safe programming languages (MSLs) can eliminate memory safety vulnerabilities.”

This concept of a ‘memory safe programming language’ leads the authors to fall into the trap of believing that tools are the problem, rather than how the tools are used.

C and C++ are memory safe programming languages when the appropriate compiler options are switched on, e.g., gcc’s sanitize flags. Rust and Ada are not memory safe programming languages when the appropriate compiler options are switched on/off, or object/function definitions include the unsafe keyword.

People argue over the definition of memory safety. At the implementation level, it includes checks that storage is not accessed outside of its defined bounds, e.g., arrays are not indexed outside the specified lower/upper bound.

I’m a great fan of array/pointer bounds checking and since the 1980s have been using bounds checking tools to check my C programs. I found bounds checking is a very cost-effective way of detecting coding mistakes.

Culture drives the (non)use of bounds checking. Pascal, Ada and now Rust have a culture of bounds checking during development, amongst other checks. C, C++, and other languages have a culture of not having switching on bounds checking.

Shipping programs with/without bounds checking enabled is a contentious issue. The three main factors are:

- Runtime performance overhead of doing the checks (which can vary from almost nothing to a factor of 5+, depending on the frequency of bounds checked accesses {checks don’t need to be made when the compiler can figure out that a particular access is always within bounds}). I would expect the performance overhead to be about the same for C/Rust compilers using the same compiler technology (as the Open source compilers do). A recent study found C (no checking) to be 1.77 times faster, on average, than Rust (with checking),

- Runtime memory overhead. Adding code to check memory accesses increases the size of programs. This can be an issue for embedded systems, where memory is not as plentiful as desktop systems (recent survey of Rust on embedded systems),

- Studies (here and here) have found that programs can be remarkably robust in the presence of errors. Developers’ everyday experience is that programs containing many coding mistakes regularly behave as expected most of the time.

If bounds checking is enabled on shipped applications, what should happen when a bounds violation is detected?

Many bounds violations are likely to be benign, and a few not so. Should users have the option of continuing program execution after a violation is flagged (assuming they have been trained to understand the program message they are seeing and are aware of the response options)?

Java programs ship with bounds checking enabled, but I have not seen any studies of user response to runtime errors.

The reason that C/C++ is the language used to write so many of the programs listed in vulnerability databases is that these languages are popular and widely used. The Rust security advisory database contains few entries because few widely used programs are written in Rust. It’s possible to write unsafe code in Rust, just like C/C++, and studies find that developers regularly write such code and security risks exist within the Rust ecosystem, just like C/C++.

There have been various attempts to implement bounds checking in x86

processors. Intel added the MPX instruction, but there were problems with the specification, and support was discontinued in 2019.

The CHERI hardware discussed in the Whitehouse report is not yet commercially available, but organizations are working towards commercial products.

Sample size needed to compare performance of two languages

A humungous organization wants to minimise one or more of: program development time/cost, coding mistakes made, maintenance time/cost, and have decided to use either of the existing languages X or Y.

To make an informed decision, it is necessary to collect the required data on time/cost/mistakes by monitoring the development process, and recording the appropriate information.

The variability of developer performance, and language/problem interaction means that it is necessary to monitor multiple development teams and multiple language/problem pairs, using statistical techniques to detect any language driven implementation performance differences.

How many development teams need to be monitored to reliably detect a performance difference driven by language used, given the variability of the major factors involved in the process?

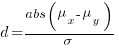

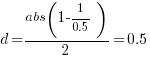

If we assume that implementation times, for the same program, have a normal distribution (it might lean towards lognormal, but the maths is horrible), then there is a known formula. Three values need to be specified, and plug into this formula: the statistical significance (i.e., the probability of detecting an effect when none is present, say 5%), the statistical power (i.e., the probability of detecting that an effect is present, say 80%), and Cohen’s d; for an overview see section 10.2.

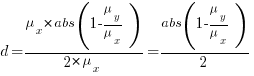

Cohen’s d is the ratio  , where

, where  and

and  is the mean value of the quantity being measured for the programs written in the respective languages, and

is the mean value of the quantity being measured for the programs written in the respective languages, and  is the pooled standard deviation.

is the pooled standard deviation.

Say the mean time to implement a program is  , what is a good estimate for the pooled standard deviation,

, what is a good estimate for the pooled standard deviation,  , of the implementation times?

, of the implementation times?

Having 66% of teams delivering within a factor of two of the mean delivery time is consistent with variation in LOC for the same program and estimation accuracy, and if anything sound slow (to me).

Rewriting the Cohen’s d ratio:

If the implementation time when using language X is half that of using Y, we get  . Plugging the three values into the

. Plugging the three values into the pwr.t.test function, in R’s pwr package, we get:

> library("pwr")

> pwr.t.test(d=0.5, sig.level=0.05, power=0.8)

Two-sample t test power calculation

n = 63.76561

d = 0.5

sig.level = 0.05

power = 0.8

alternative = two.sided

NOTE: n is number in *each* group |

In other words, data from 64 teams using language X and 64 teams using language Y is needed to reliably detect (at the chosen level of significance and power) whether there is a difference in the mean performance (of whatever was measured) when implementing the same project.

The plot below shows sample size required for a t-test testing for a difference between two means, for a range of X/Y mean performance ratios, with red line showing the commonly used values (listed above) and other colors showing sample sizes for more relaxed acceptance bounds (code):

Unless the performance difference between languages is very large (e.g., a factor of three) the required sample size is going to push measurement costs into many tens of millions (£1 million per team, to develop a realistic application, multiplied by two and then multiplied by sample size).

For small programs solving certain kinds of problems, a factor of three, or more, performance difference between languages is not unusual (e.g., me using R for this post, versus using Python). As programs grow, the mundane code becomes more and more dominant, with the special case language performance gains playing an outsized role in story telling.

There have been studies comparing pairs of languages. Unfortunately, most have involved students implementing short problems, one attempted to measure the impact of programming language on coding competition performance (and gets very confused), the largest study I know of compared Fortran and Ada implementations of a satellite ground station support system.

The performance difference detected may be due to the particular problem implemented. The language/problem performance correlation can be solved by implementing a wide range of problems (using 64 teams per language).

A statistically meaningful comparison of the implementation costs of language pairs will take many years and cost many millions. This question is unlikely to every be answered. Move on.

My view is that, at least for the widely used languages, the implementation/maintenance performance issues are primarily driven by the ecosystem, rather than the language.

2023 in the programming language standards’ world

Two weeks ago I was on a virtual meeting of IST/5, the committee responsible for programming language standards in the UK. IST/5 has a new chairman, Guy Davidson, whose efficiency is very unstandard’s like.

It’s been 18 months since I last reported on the programming language standards’ world, what has been going on?

2023 is going to be a bumper year for the publication of revised Standards of long-established programming language: COBOL, Fortran, C, and C++ (a revised Standard for Ada was published last year).

Yes, COBOL; a new COBOL Standard was published in January. Reports of its death were premature, e.g., my 2014 post suggesting that the latest version would be the last version of the Standard, and the closing of PL22.4, the US Cobol group, in 2017. There has even been progress on the COBOL front end for gcc, which now supports COBOL 85.

The size of the COBOL Standard has leapt from 955 to 1,229 pages (around new 200 pages in the normative text, 100 in the annexes). Comparing the 2014/2023 documents, I could not see any major additions, just lots of small changes spread throughout the document.

Every Standard has a project editor, the person tasked with creating a document that reflects the wishes/votes of its committee; the project editor sends the agreed upon document to ISO to be published as the official ISO Standard. The ISO editors would invariably request that the project editor make tiresome organizational changes to the document, and then add a front page and ISO copyright notice; from time to time an ISO editor took it upon themselves to reformat a document, sometimes completely mangling its contents. The latest diktat from ISO requires that submitted documents use the Cambria font. Why Cambria? What else other than it is the font used by the Microsoft Word template promoted by ISO as the standard format for Standard’s documents.

All project editors have stories to tell about shepherding their document through the ISO editing process. With three Standards (COBOL lives in a disjoint ecosystem) up for publication this year, ISO editorial issues have become a widespread topic of discussion in the bubble that is language standards.

Traditionally, anybody wanting to be actively involved with a language standard in the UK had to find the contact details of the convenor of the corresponding language panel, and then ask to be added to the panel mailing list. My, and others, understanding was that provided the person was a UK citizen or worked for a UK domiciled company, their application could not be turned down (not that people were/are banging on the door to join). BSI have slowly been computerizing everything, and, as of a few years ago, people can apply to join a panel via a web page; panel members are emailed the CV of applicants and asked if “… applicant’s knowledge would be beneficial to the work programme and panel…”. In the US, people pay an annual fee for membership of a language committee ($1,340/$2,275). Nobody seems to have asked whether the criteria for being accepted as a panel member has changed. Given that BSI had recently rejected somebodies application to join the C++ panel, the C++ panel convenor accepted the action to find out if the rules have changed.

In December, BSI emailed language panel members asking them to confirm that they were actively participating. One outcome of this review of active panel membership was the disbanding of panels with ‘few’ active members (‘few’ might be one or two, IST/5 members were not sure). The panels that I know to have survived this cull are: Fortran, C, Ada, and C++. I did not receive any email relating to two panels that I thought I was a member of; one or more panel convenors may be appealing their panel being culled.

Some language panels have been moribund for years, being little more than bullet points on the IST/5 agenda (those involved having retired or otherwise moved on).

Programming Languages: History and Fundamentals

Programming Languages: History and Fundamentals by Jean E. Sammet is often cited in discussions of language history, but very rarely read (I appreciate that many oft cited books have not been read by those citing them, but age further reduces the likelihood that anybody has read this book; it was published in 1969). I read this book as an undergraduate, but did not think much of it. For around five years it has been on my list of books to buy, should a second-hand copy become available below £10 (I buy anything vaguely interesting below this price, with most ending up left on trains or the book table of coffee shops).

Thanks to Adam Gashlin the Internet Archive now contains a downloadable copy.

The list of 120 languages covered contains a handful of the 28 languages covered in an article from 1957. Sammet says that of the 120, 20 are already dead or on obsolete computers (i.e., it is unlikely that another compiler will be written), and that about 15 are widely used/implemented).

Today, the book is no longer a discussion of the recent past, but a window in to the Cambrian explosion of programming languages that happened in the 1960s (almost everything since then has been a variation on a theme); languages from the 1950s are also included.

How does the material appear to me from a 2022 vantage-point?

The organization of the book reminded me that programming languages were once categorized by application domain, i.e., scientific/engineering users, business users, and string & list processing (i.e., academic users). This division reflected the market segmentation for computer hardware (back then, personal computers were still in the realm of science fiction). Modern programming language books (e.g., Scott’s “Programming Language Pragmatics”) often organize material based on implementation details, e.g., lexical analysis, and scoping rules.

The overview of programming languages given in the first three chapters covers nearly all the basic issues that beginners are taught today, but the emphasis is different (plus typographical differences, such as keyword spelt ‘key word’).

Two major language constructs are missing: Dynamic storage allocation is not discussed: Wirth’s book Algorithms + Data Structures = Programs is seven years in the future, and Kernighan and Ritchie’s The C Programming Language nine years; Simula gets a paragraph, but no mention of the object-oriented concepts it introduced.

What is a programming language, and what are the distinguishing features that make some of them high-level programming languages?

These questions may sound pointless or obvious today, but people used to spend lots of time arguing over what was, or was not, a high-level language.

Sammet says: “… the first characteristic of a programming language is that the user can write a program without knowing much—if anything—about the physical characteristics of the machine on which the program is to be run.”, and goes on to infer: “… a major characteristic of a programming language is that there must be a reasonable potential of having a source program written in that language run on two computers with different machine codes without rewriting the source program. … In most programming languages, some—but often very little—rewriting of the source program is necessary.”

The reason that some rewriting of the source was likely to be needed is that there were often a lot of small variations between compilers for the same language. Compilers tended to be bespoke, i.e., the Fortran compiler for the X cpu running OS Y was written specifically for that combination. Retargetting an existing compiler to a new cpu or OS was much talked about, but it was more fun to write a new compiler (and anyway, support for new features was needed, and it was simpler to start from scratch; page 149 lists differences in Fortran compilers across IBM machines). It didn’t help that there was also a lot of variation in fundamental quantities such as word length, e.g., 16, 18, 20, 24, 32, 36, 40, 48, 60 bit words; see page 18 of Dictionary of Computer Languages.

Sammet makes the distinction: “One of the prime differences between assembly and higher level languages is that to date the latter do not have the capability of modifying themselves at execution time.”

Sammet then goes on to list the advantages and disadvantages of what she calls higher level languages. Most of the claimed advantages will be familiar to readers: “Ease of Learning”, “Ease of Coding and Understanding”, “Ease of Debugging”, and “Ease of Maintaining and Documenting”. The disadvantages included: “Time Required for Compiling” (the issue here is converting assembler source to object code is much faster than compiling a high-level language), “Inefficient Object Code” (the translation process was often a one-to-one mapping of what was written, e.g., little reuse of register contents), “Difficulties in Debugging Without Learning Machine Language” (symbolic debuggers are still in the future).

Sammet’s observation: “In spite of the fact that higher level languages have been with us for over 10 years, there has been relatively little quantitative or qualitative analysis of their advantages and disadvantages.” is still true 50 years later.

If you enjoy learning about lots of different languages, you will like this book. The discussion of specific languages contains copious examples, which for me brought things to life.

Sites such as the Internet Archive and Bitsavers make the book’s references accessible (there are a few I had not seen before), and offer readers a path to pre-Cambrian times.

Saul Rosen’s 1967 book “Programming Systems and Languages” is sometimes cited in discussions of programming language history. This book is a collection of papers that discuss a variety of languages and the operating systems that support them. Fewer languages are covered, but in more depth, along with lots of implementation details. Again, lots of interesting references.

Programming language similarity based on their traits

A programming language is sometimes described as being similar to another, more wide known, language.

How might language similarity be measured?

Biologists ask a very similar question, and research goes back several hundred years; phenetics (also known as taximetrics) attempts to classify organisms based on overall similarity of observable traits.

One answer to this question is based on distance matrices.

The process starts by flagging the presence/absence of each observed trait. Taking language keywords (or reserved words) as an example, we have (for a subset of C, Fortran, and OCaml):

if then function for do dimension object C 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 Fortran 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 OCaml 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 |

The distance between these languages is calculated by treating this keyword presence/absence information as an n-dimensional space, with each language occupying a point in this space. The following shows the Euclidean distance between pairs of languages (using the full dataset; code+data):

C Fortran OCaml C 0 7.615773 8.717798 Fortran 7.615773 0 8.831761 OCaml 8.717798 8.831761 0 |

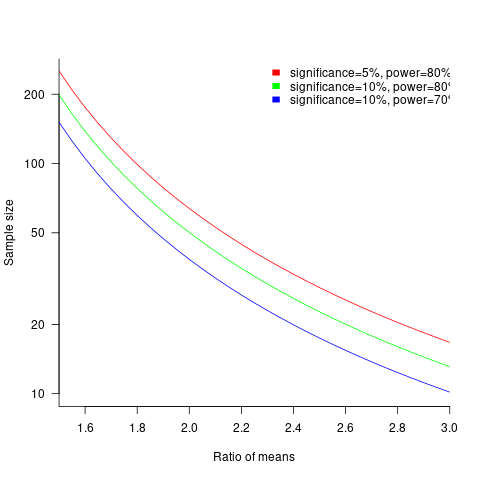

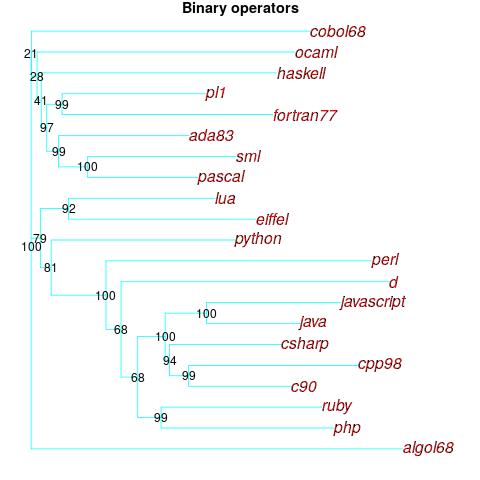

Algorithms are available to map these distance pairs into tree form; for biological organisms this is known as a phylogenetic tree. The plot below shows such a tree derived from the keywords supported by 21 languages (numbers explained below, code+data):

How confident should we be that this distance-based technique produced a robust result? For instance, would a small change to the set of keywords used by a particular language cause it to appear in a different branch of the tree?

The impact of small changes on the generated tree can be estimated using a bootstrap technique. The particular small-change algorithm used to estimate confidence levels for phylogenetic trees is not applicable for language keywords; genetic sequences contain multiple instances of four DNA bases, and can be sampled with replacement, while language keywords are a set of distinct items (i.e., cannot be sampled with replacement).

The bootstrap technique I used was: for each of the 21 languages in the data, was: add keywords to one language (the number added was 5% of the number of its existing keywords, randomly chosen from the set of all language keywords), calculate the distance matrix and build the corresponding tree, repeat 100 times. The 2,100 generated trees were then compared against the original tree, counting how many times each branch remained the same.

The numbers in the above plot show the percentage of generated trees where the same branching decision was made using the perturbed keyword data. The branching decisions all look very solid.

Can this keyword approach to language comparison be applied to all languages?

I think that most languages have some form of keywords. A few languages don’t use keywords (or reserved words), and there are some edge cases. Lisp doesn’t have any reserved words (they are functions), nor technically does Pl/1 in that the names of ‘word tokens’ can be defined as variables, and CHILL implementors have to choose between using Cobol or PL/1 syntax (giving CHILL two possible distinct sets of keywords).

To what extent are a language’s keywords representative of the language, compared to other languages?

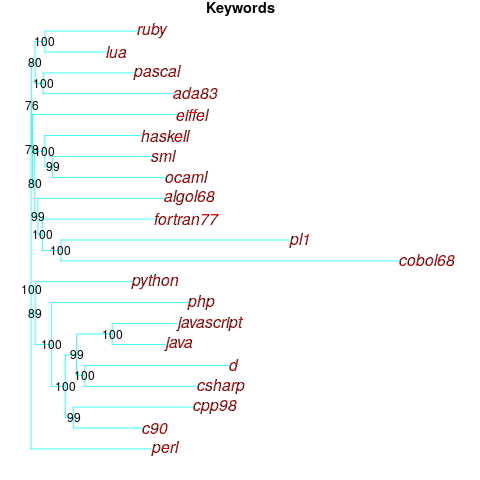

One way to try and answer this question is to apply the distance/tree approach using other language traits; do the resulting trees have the same form as the keyword tree? The plot below shows the tree derived from the characters used to represent binary operators (code+data):

A few of the branching decisions look as-if they are likely to change, if there are changes to the keywords used by some languages, e.g., OCaml and Haskell.

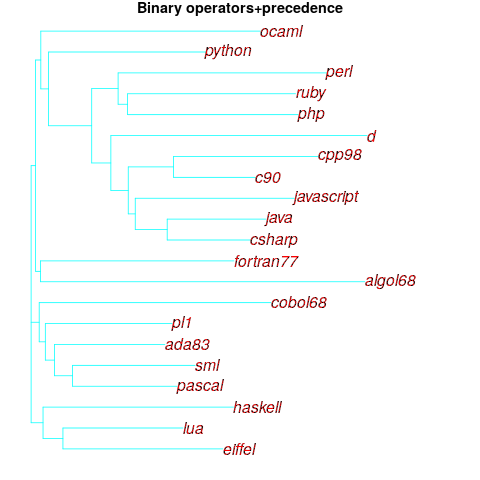

Binary operators don’t just have a character representation, they can also have a precedence and associativity (neither are needed in languages whose expressions are written using prefix or postfix notation).

The plot below shows the tree derived from combining binary operator and the corresponding precedence information (the distance pairs for the two characteristics, for each language, were added together, with precedence given a weight of 20%; see code for details).

No bootstrap percentages appear because I could not come up with a simple technique for handling a combination of traits.

Are binary operators more representative of a language than its keywords? Would a combined keyword/binary operator tree would be more representative, or would more traits need to be included?

Does reducing language comparison to a single number produce something useful?

Languages contain a complex collection of interrelated components, and it might be more useful to compare their similarity by discrete components, e.g., expressions, literals, types (and implicit conversions).

What is the purpose of comparing languages?

If it is for promotional purposes, then a measurement based approach is probably out of place.

If the comparison has a source code orientation, weighting items by source code occurrence might produce a more applicable tree.

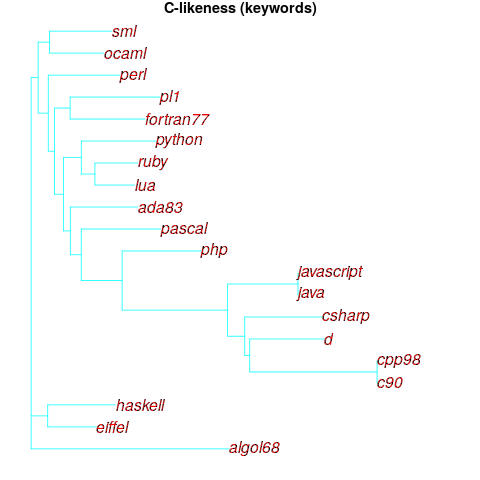

Sometimes one language is used as a reference, against which others are compared, e.g., C-like. How ‘C-like’ are other languages? Taking keywords as our reference-point, comparing languages based on just the keywords they have in common with C, the plot below is the resulting tree:

I had expected less branching, i.e., more languages having the same distance from C.

New languages can be supported by adding a language file containing the appropriate trait information. There is a Github repo, prog-lang-traits, send me a pull request to add your language file.

It’s also possible to add support for more language traits.

Creating and evolving a programming language: funding

The funding for artists and designers/implementors of programming languages shares some similarities.

Rich patrons used to sponsor a few talented painters/sculptors/etc, although many artists had no sponsors and worked for little or no money. Designers of programming languages sometimes have a rich patron, in the form of a company looking to gain some commercial advantage, with most language designers have a day job and work on their side project that might have a connection to their job (e.g., researchers).

Why would a rich patron sponsor the creation of an art work/language?

Possible reasons include: Enhancing the patron’s reputation within the culture in which they move (attracting followers, social or commercial), and influencing people’s thinking (to have views that are more in line with those of the patron).

The during 2009-2012 it suddenly became fashionable for major tech companies to have their own home-grown corporate language: Go, Rust, Dart and Typescript are some of the languages that achieved a notable level of brand recognition. Microsoft, with its long-standing focus on developers, was ahead of the game, with the introduction of F# in 2005 (and other languages in earlier and later years). The introduction of Swift and Hack in 2014 were driven by solid commercial motives (i.e., control of developers and reduced maintenance costs respectively); Google’s adoption of Kotlin, introduced by a minor patron in 2011, was driven by their losing of the Oracle Java lawsuit.

Less rich patrons also sponsor languages, with the idiosyncratic Ivor Tiefenbrun even sponsoring the creation of a bespoke cpu to speed up the execution of programs written in the company language.

The benefits of having a rich sponsor is the opportunity it provides to continue working on what has been created, evolving it into something new.

Self sponsored individuals and groups also create new languages, with recent more well known examples including Clojure and Julia.

What opportunities are available for initially self sponsored individuals to support themselves, while they continue to work on what has been created?

The growth of the middle class, and its interest in art, provided a means for artists to fund their work by attracting smaller sums from a wider audience.

In the last 10-15 years, some language creators have fostered a community driven approach to evolving and promoting their work. As well as being directly involved in working on the language and its infrastructure, members of a community may also contribute or help raise funds. There has been a tiny trickle of developers leaving their day job to work full time on ‘their’ language.

The term Hedonism driven development is a good description of this kind of community development.

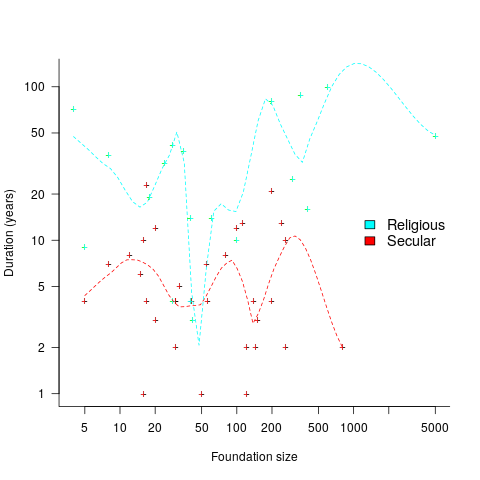

People have been creating new languages since computers were invented, and I don’t expect this desire to create new languages to stop anytime soon. How long might a language community be expected to last?

Having lots of commercially important code implemented in a language creates an incentive for that language’s continual existence, e.g., companies paying for support. When little or co commercial important code is available to create an external incentive, a language community will continue to be active for as long as its members invest in it. The plot below shows the lifetime of 32 secular and 19 religious 19th century American utopian communities, based on their size at foundation; lines are fitted loess regression (code+data):

How many self-sustaining language communities are there, and how many might the world’s population support?

My tracking of new language communities is a side effect of the blogs I follow and the few community sites a visit regularly; so a tiny subset of the possibilities. I know of a handful of ‘new’ language communities; with ‘new’ as in not having a Wikipedia page (yet).

One list contains, up until 2005, 7,446 languages. I would not be surprised if this was off by almost an order of magnitude. Wikipedia has a very idiosyncratic and brief timeline of programming languages, and a very incomplete list of programming languages.

I await a future social science PhD thesis for a more thorough analysis of current numbers.

Recent Comments