Latest Blog Posts

Quick and dirty loading of CSV files

Posted by Hubert 'depesz' Lubaczewski on 2026-01-07 at 00:10

PostgreSQL Meetup in Frankfurt December 2025

Posted by Andreas Scherbaum on 2026-01-06 at 22:00

Small improvement for pretty-printing in paste.depesz.com

Posted by Hubert 'depesz' Lubaczewski on 2026-01-06 at 15:13

What is index overhead on writes?

Posted by Hubert 'depesz' Lubaczewski on 2026-01-06 at 11:57

pg_acm is here!

Posted by Henrietta Dombrovskaya on 2026-01-06 at 11:15

I am writing this post over the weekend but scheduling it to be published on Tuesday, after the PG DATA CfP closes, because I do not want to distract anyone, including myself, from the submission process.

A couple of months ago, I created a placeholder in my GitHub, promising to publish pg_acm before the end of the year. The actual day I pushed the initial commit was January 3, but it still counts, right? At least, it happened before the first Monday of 2026!

It has been about two years since I first spoke publicly about additional options I would love to see in PostgreSQL privileges management. Now I know it was not the most brilliant idea to frame it as “what’s wrong with Postgres permissions,” and this time I am much better with naming.

pg_acm stands for “Postgres Access Control Management.” The key feature of this framework is that each schema is created with a set of predefined roles and default privileges, which makes it easy to achieve complete isolation between different projects sharing the same database, and allows authorized users to manage access to their data without having superuser privileges.

Please take a look, give it a try, and let me know what’s wrong with my framework

Stabilizing Benchmarks

Posted by Tomas Vondra on 2026-01-06 at 10:00

I do a fair amount of benchmarks as part of development, both on my own patches and while reviewing patches by others. That often requires dealing with noise, particularly for small optimizations. Here’s an overview of ways I use to filter out random variations / noise.

Most of the time it’s easy - the benefits are large and obvious. Great! But sometimes we need to care about cases when the changes are small (think less than 5%).

Dissecting PostgreSQL Data Corruption

Posted by Josef Machytka in credativ on 2026-01-06 at 09:03

PostgreSQL 18 made one very important change – data block checksums are now enabled by default for new clusters at cluster initialization time. I already wrote about it in my previous article. I also mentioned that there are still many existing PostgreSQL installations without data checksums enabled, because this was the default in previous versions. In those installations, data corruption can sometimes cause mysterious errors and prevent normal operational functioning. In this post, I want to dissect common PostgreSQL data corruption modes, to show how to diagnose them, and sketch how to recover from them.

Corruption in PostgreSQL relations without data checksums surfaces as low-level errors like “invalid page in block xxx”, transaction ID errors, TOAST chunk inconsistencies, or even backend crashes. Unfortunately, some backup strategies can mask the corruption. If the cluster does not use checksums, then tools like pg_basebackup, which copy data files as they are, cannot perform any validation of data, so corrupted pages can quietly end up in a base backup. If checksums are enabled, pg_basebackup verifies them by default unless –no-verify-checksums is used. In practice, these low-level errors often become visible only when we directly access the corrupted data. Some data is rarely touched, which means corruption often surfaces only during an attempt to run pg_dump — because pg_dump must read all data.

Typical errors include:

[...]-- invalid page in a table: pg_dump: error: query failed: ERROR: invalid page in block 0 of relation base/16384/66427 pg_dump: error: query was: SELECT last_value, is_called FROM public.test_table_bytea_id_seq -- damaged system columns in a tuple: pg_dump: error: Dumping the contents of table "test_table_bytea" failed: PQgetResult() failed. pg_dump: error: Error message from server: ERROR: could not access status of transaction 3353862211 DETAIL: Could not open file "pg_xact/0C7E": No such file or directory. pg_dump: error: The command was: COPY publ

Exploration: CNPG Logical Replication in PostgreSQL

Posted by Umut TEKIN in Cybertec on 2026-01-06 at 06:05

Introduction

PostgreSQL has built-in support for logical replication. Unlike streaming replication, which works at the block level, logical replication replicates data changes based on replica-identities, usually primary keys, rather than exact block addresses or byte-by-byte copies.

PostgreSQL logical replication follows a publish–subscribe model. One or more subscribers can subscribe to one or more publications defined on a publisher node. Subscribers pull data changes from the publications they are subscribed to, and they can also act as publishers themselves, enabling cascading logical replication.

Logical replication has many use cases, such as;

- Nearly zero downtime PostgreSQL upgrades

- Data migrations

- Consolidating multiple databases for reporting purposes

- Real time analytics

- Replication between PostgreSQL instances on different platforms

Other than these cases, if your PostgreSQL instance is running on RHEL and you want to migrate to CNPG, streaming replication can be used. However, since CNPG images are based on Debian, the locale configuration must be compatible, and when using libc-based collations, differences in glibc versions can affect collation behavior. That is why we will practice logical replication setup to avoid these limitations.

Preparation of The Source Cluster

The specifications of the source PostgreSQL instance:

cat /etc/os-release | head -5

NAME="Rocky Linux"

VERSION="10.1 (Red Quartz)"

ID="rocky"

ID_LIKE="rhel centos fedora"

VERSION_ID="10.1"

psql -c "select version();"

version

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PostgreSQL 18.1 on x86_64-pc-linux-gnu, compiled by gcc (GCC) 14.3.1 20250617 (Red Hat 14.3.1-2), 64-bit

(1 row)

Populating some test data using pgbench and checking pgbench_accounts table:

/usr/pgsql-18/bin/pgbench -i -s 10 dropping old tables...[...]

PostgreSQL 18 RETURNING Enhancements: A Game Changer for Modern Applications

Posted by Ahsan Hadi in pgEdge on 2026-01-06 at 05:45

PostgreSQL 18 has arrived with some fantastic improvements, and among them, the RETURNING clause enhancements stand out as a feature that every PostgreSQL developer and DBA should be excited about. In this blog, I'll explore these enhancements, with particular focus on the MERGE RETURNING clause enhancement, and demonstrate how they can simplify your application architecture and improve data tracking capabilities.

Background: The RETURNING Clause Evolution

The RETURNING clause has been a staple of Postgres for years, allowing , , and operations to return data about the affected rows. This capability eliminates the need for follow-up queries, reducing round trips to the database and improving performance. However, before Postgres 18, the RETURNING clause had significant limitations that forced developers into workarounds and compromises.In Postgres 17, the community introduced RETURNING support for MERGE statements (commit c649fa24a), which was already a major step forward. MERGE itself had been introduced back in Postgres 15, providing a powerful way to perform conditional , , or operations in a single statement, but without RETURNING didn’t provide an easy way to see what you'd accomplished.What's New in PostgreSQL 18?

Postgres 18 takes the RETURNING clause to the next level by introducing OLD and NEW aliases (commit 80feb727c8), authored by Dean Rasheed and reviewed by Jian He and Jeff Davis. This enhancement fundamentally changes how you can capture data during DML operations.The Problem Before PostgreSQL 18

Previously, the RETURNING clause had these limitations; despite being syntactically similar, when applied to different query types:- INSERT and UPDATE

- could only return new/current values.

- DELETE

- could only return old values

- MERGE

- would return values based on the internal action executed (

- INSERT

- ,

- UPDATE

- , or

- DELETE

- ).

Inventing A Cost Model for PostgreSQL Local Buffers Flush

Posted by Andrei Lepikhov in pgEdge on 2026-01-05 at 12:39

In this post, I describe experiments on the write-versus-read costs of PostgreSQL's temporary buffers. For the sake of accuracy, the PostgreSQL functions set is extended with tools to measure buffer flush operations. The measurements show that writes are approximately 30% slower than reads. Based on these results, the cost estimation formula for the optimiser has been proposed:

flush_cost = 1.30 × dirtied_bufs + 0.01 × allocated_bufs.

Introduction

Temporary tables in PostgreSQL have always been parallel restricted. From my perspective, the reasoning is straightforward: temporary tables exist primarily to compensate for the absence of relational variables, and for performance reasons, they should remain as simple as possible. Since PostgreSQL parallel workers behave like separate backends, they don't have access to the leader process's local state, where temporary tables reside. Supporting parallel operations on temporary tables would significantly increase the complexity of this machinery.

However, we now have at least two working implementations of parallel temporary table support: Postgres Pro and Tantor. One more reason: identification of temporary tables within a UTILITY command is an essential step toward auto DDL in logical replication. So, maybe it is time to propose such a feature for PostgreSQL core.

After numerous code improvements over the years, AFAICS, only one fundamental problem remains: temporary buffer pages are local to the leader process. If these pages don't match the on-disk table state, parallel workers cannot access the data.

A comment in the code (80558c1) made by Robert Haas in 2015 clarifies the state of the art:

/*

* Currently, parallel workers can't access the leader's temporary

* tables. We could possibly relax this if we wrote all of its

* local buffers at the start of the query and made no changes

* thereafter (maybe we could allow hint bit changes), and if we

* taught the workers to read them. Writing a large number of

* temporary buffers could be PostgreSQL Table Rename and Views – An OID Story

Posted by Deepak Mahto on 2026-01-05 at 08:53

Recently during a post-migration activity, we had to populate a very large table with a new UUID column (NOT NULL with a default) and backfill it for all existing rows.

Instead of doing a straight:

ALTER TABLE ... ADD COLUMN ... DEFAULT ... NOT NULL;

we chose the commonly recommended performance approach:

- Create a new table (optionally UNLOGGED),

- Copy the data,

- Rename/swap the tables.

This approach is widely used to avoid long-running locks and table rewrites but it comes with hidden gotchas. This post is about one such gotcha: object dependencies, especially views, and how PostgreSQL tracks them internally using OIDs.

A quick but important note

On PostgreSQL 11+, adding a column with a constant default is a metadata-only operation and does not rewrite the table. However:

- This is still relevant when the default is volatile (like

uuidv7()), - Or when you must immediately enforce

NOT NULL, - Or when working on older PostgreSQL versions,

- Or when rewriting is unavoidable for other reasons.

So the rename approach is still valid but only when truly needed.

The Scenario: A Common Performance Optimization

Picture this: You’ve got a massive table with millions of rows, and you need to add a column with unique UUID default value and not null constraint values. The naive approach? Just run ALTER TABLE ADD COLUMN. But wait for large tables, this can lock your table while PostgreSQL rewrites every single row and can incur considerable time.

So what do we do? We get clever. We use the intermediate table(we can also use unlogged table) with rename trick, below is an sample created to show the scenario’s.

drop table test1;

create table test1

(col1 integer, col2 text, col3 timestamp(0));

insert into test1

select col1, col1::text , (now() - (col1||' hour')::interval)

from generate_series(1,1000000) as col1;

create view vw_test1 as

select * from test1;

CREATE TABLE test1_new

(like test1 including all);

alteChaos testing the CloudNativePG project

Posted by Floor Drees in CloudNativePG on 2026-01-05 at 00:00

PgPedia Week, 2025-12-07

Posted by Ian Barwick on 2026-01-04 at 23:44

Waiting for PostgreSQL 19 – Implement ALTER TABLE … MERGE/SPLIT PARTITIONS … command

Posted by Hubert 'depesz' Lubaczewski on 2026-01-04 at 17:30

Sticking with Open Source: pgEdge and CloudNativePG

Posted by Floor Drees in CloudNativePG on 2026-01-02 at 00:00

CloudNativePG in 2025: CNCF Sandbox, PostgreSQL 18, and a new era for extensions

Posted by Gabriele Bartolini in EDB on 2025-12-31 at 11:50

2025 marked a historic turning point for CloudNativePG, headlined by its acceptance into the CNCF sandbox and a subsequent application for incubation. Throughout the year, the project transitioned from a high-performance operator to a strategic architectural partner within the cloud-native ecosystem, collaborating with projects like Cilium and Keycloak. Key milestones included the co-development of the extension_control_path feature for PostgreSQL 18, revolutionising extension management via OCI images, and the General Availability of the Barman Cloud Plugin. With nearly 880 commits (marking five consecutive years of high-velocity development) and over 132 million downloads, CloudNativePG has solidified its position as the standard for declarative, resilient, and sovereign PostgreSQL on Kubernetes.

PostgreSQL Recovery Internals

Posted by Imran Zaheer in Cybertec on 2025-12-30 at 05:30

Modern databases must know how to handle failures gracefully, whether they are system failures, power failures, or software bugs, while also ensuring that committed data is not lost. PostgreSQL achieves this with its recovery mechanism; it allows the recreation of a valid functioning system state from a failed one. The core component that makes this possible is Write-Ahead Logging (WAL); this means PostgreSQL records all the changes before they are applied to the data files. This way, WAL makes the recovery smooth and robust.

In this article, we are going to look at the under-the-hood mechanism for how PostgreSQL undergoes recovery and stays consistent and how the same mechanism powers different parts of the database. We will see the recovery lifecycle, recovery type selection, initialization and execution, how consistent states are determined, and reading WAL segment files for the replay.

We will show how PostgreSQL achieves durability (the "D" in ACID), as database recovery and the WAL mechanism together ensure that all the committed transactions are preserved. This plays a fundamental role in making PostgreSQL fully ACID compliant so that users can trust that their data is safe at all times.

Note: The recovery internals described in this article are based on the PostgreSQL version 18.1.

Overview

PostgreSQL recovery involves replaying the WAL records on the server to restore the database to a consistent state. This process ensures data integrity and protects against data loss in the event of system failures. In such scenarios, PostgreSQL efficiently manages its recovery processes, returning the system to a healthy operational state. Furthermore, in addition to addressing system failures and crashes, PostgreSQL's core recovery mechanism performs several other critical functions.

The recovery mechanism, powered by WAL and involving the replay of records until a consistent state is achieved (WAL → Redo → Consistency), facilitates several advanced database capabilities:

- R

PostgreSQL Contributor Story: Manni Wood

Posted by Floor Drees in EDB on 2025-12-29 at 08:59

FOSS4GNA 2025: Summary

Posted by REGINA OBE in PostGIS on 2025-12-28 at 23:37

Free and Open Source for Geospatial North America (FOSS4GNA) 2025 was running November 3-5th 2025 and I think it was one of the better FOSS4GNAs we've had. I was on the programming and workshop committees and we were worried with the government shutdown that things could go badly since we started getting people withdrawing their talks and workshops very close to curtain time. Despite our attendance being lower than prior years, it felt crowded enough and on the bright side, people weren't fighting for chairs to sit even in the most crowded talks. The FOSS4G 2025 International happened 2 weeks after, in Auckland, New Zealand, and that I heard had a fairly decent turn-out too.

Continue reading "FOSS4GNA 2025: Summary"Contributions for week 53, 2025

Posted by Cornelia Biacsics in postgres-contrib.org on 2025-12-28 at 21:22

Emma Sayoran organized a PUG Armenia speed networking meetup on December 25 2025.

FOSDEM PGDay 2026 Schedule announced on Dec 23 2025. Call for Paper Committee:

- Teresa Lopes

- Stefan Fercot

- Flavio Gurgel

Community Blog Posts:

- Chiira B. Mwangi I joined a community!

Improved Quality in OpenStreetMap Road Network for pgRouting

Posted by Ryan Lambert on 2025-12-28 at 05:01

Recent changes in the software bundled in PgOSM Flex resulted in unexpected improvements when using OpenStreetMap roads data for routing. The short story: routing with PgOSM Flex 1.2.0 is faster, easier, and produces higher quality data for routing! I came to this conclusion after completing a variety of testing with the old and new versions of PgOSM Flex. This post outlines my testing and findings.

The concern I had before this testing was that the variety of changes involved in preparing data for routing in PgOSM Flex 1.2.0 might have degraded routing quality. I am beyond thrilled with what I found instead. Quality of the generated network didn't suffer at all, it was a major win!

What Changed?

The changes started with PgOSM Flex 1.1.1 by bumping internal versions used in PgOSM Flex to Postgres 18, PostGIS 3.6, osm2pgsql 2.2.0, and Debian 13. There was not expected to be any significant changes bundled in that release. After v1.1.1 was released, it came to my attention that pgRouting 4.0 had been released and that update broke the routing instructions in PgOSM Flex's documentation. This was thankfully reported by Travis Hathaway who also helped verify the updates to the process.

pgRouting 4 removed the

pgr_nodeNetwork,pgr_createTopology, andpgr_analyzeGraphfunctions. Removing these functions was the catalyst for the changes made in PgOSM Flex 1.2.0. I had used thosepgr_*functions as part of my core process in data preparation for routing for as long as I have used pgRouting.

After adjusting the documentation it became clear there were performance issues using the replacement functions in pgRouting 4.0, namely in pgr_separateTouching(). The performance issue in the pgRouting function is reported as pgrouting#3010. Working through the performance challenges resulted in PgOSM Flex 1.1.2 and ultimately PgOSM Flex 1.2.0 that now uses a custom procedure to prepare the edge network far better suited to OpenStreetMap data.

PostgreSQL as a Graph Database: Who Grabbed a Beer Together?

Posted by Taras Kloba on 2025-12-27 at 00:00

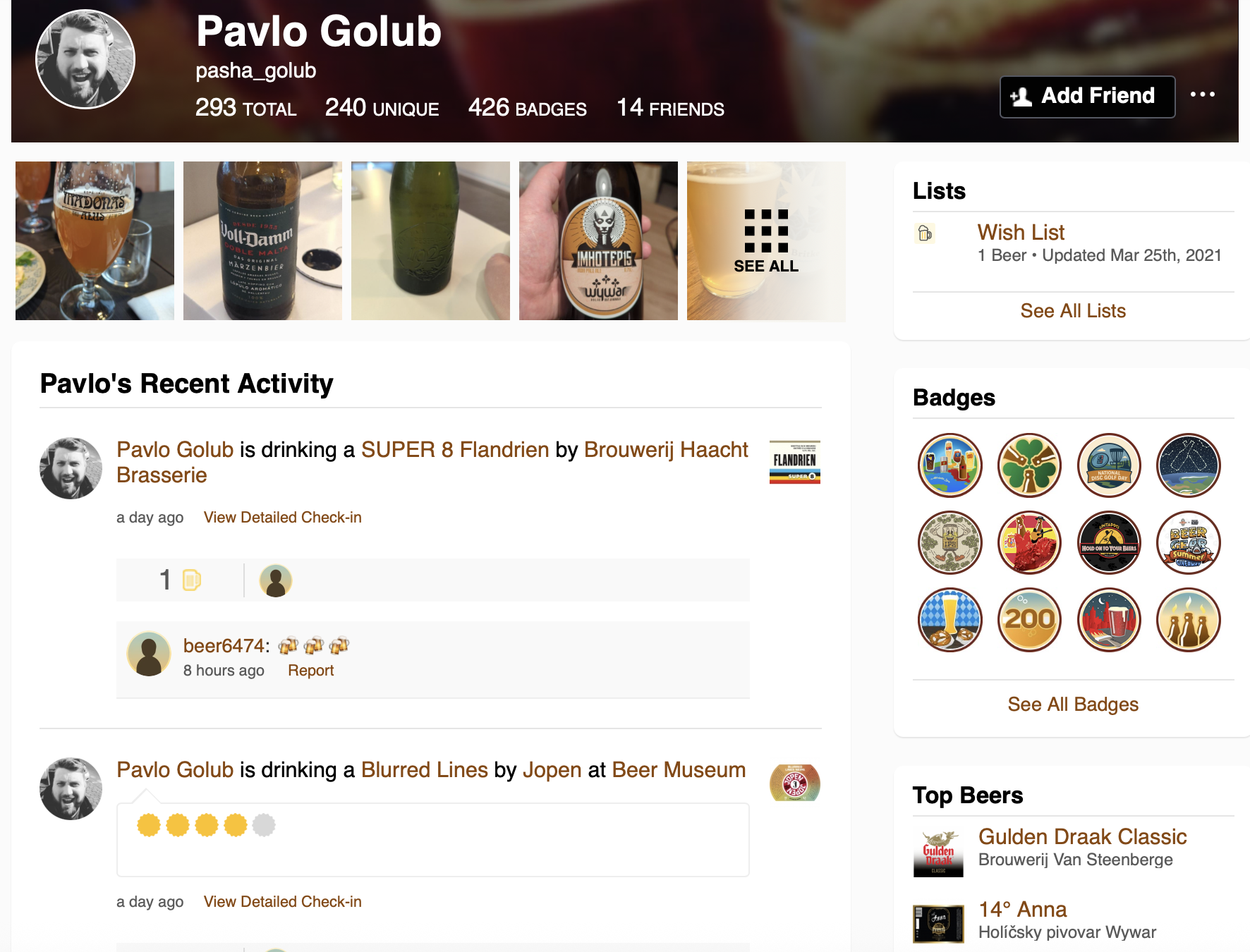

Graph databases have become increasingly popular for modeling complex relationships in data. But what if you could leverage graph capabilities within the familiar PostgreSQL environment you already know and love? In this article, I’ll explore how PostgreSQL can serve as a graph database using the Apache AGE extension, demonstrated through a fun use case: analyzing social connections in the craft beer community using Untappd data.

This article is based on my presentation at PgConf.EU 2025 in Riga, Latvia. Special thanks to Pavlo Golub, my co-founder of the PostgreSQL Ukraine community, whose Untappd account served as the perfect example for this demonstration.

Pavlo Golub’s Untappd profile - the starting point for our graph analysis

Pavlo Golub’s Untappd profile - the starting point for our graph analysis

Why Graph Databases?

Traditional relational databases excel at storing structured data in tables, but they can struggle when dealing with highly interconnected data. Consider a social network where you want to find the shortest path between two users through their mutual connections—this requires recursive queries with CTEs, joining multiple tables, and becomes increasingly complex as the depth of relationships grows.

You might say: “But I can do this with relational tables!” And yes, you would be right in some cases. But graphs offer a different approach that makes certain operations much more intuitive and efficient.

Graph databases model data as nodes (vertices) and edges (relationships), making them ideal for:

- Social networks

- Recommendation engines

- Fraud detection

- Knowledge graphs

- Network topology analysis

Basic Terms in Graph Theory

Before diving into implementation, let’s establish some fundamental concepts:

Vertices (Nodes) are the fundamental units or points in a graph. You can think of them like tables in relational databases. They represent entities, objects, or data items—for example, individuals in a social network.

Edges (Links/Relationships) are the connections between nodes that indicate relationships

[...]New PostgreSQL Features I Developed in 2025

Posted by Shinya Kato on 2025-12-25 at 23:00

Introduction

I started contributing to PostgreSQL around 2020. This year I wanted to work harder, so I will explain the PostgreSQL features I developed and committed in 2025.

I also committed some other patches, but they were bug fixes or small document changes. Here I explain the ones that seem most useful.

These are mainly features in PostgreSQL 19, now in development. They may be reverted before the final release.

Added a document that recommends default psql settings when restoring pg_dump backups

- Title: Doc: recommend "psql -X" for restoring pg_dump scripts.

- Committer: Tom Lane

- Date: Sat, 25 Jan 2025

- Link: https://git.postgresql.org/gitweb/?p=postgresql.git;a=commit;h=d83a108c10a3ec886a24c620a915aa2c5bc023aa

When you restore a dump file made by pg_dump with psql, you may get errors if psql is using non-default settings (I saw it with AUTOCOMMIT=off). The change is only in the docs. It recommends using the psql option -X (--no-psqlrc) to avoid reading the psql config file.

For psql config file psqlrc, see my past blog:

https://zenn.dev/shinyakato/articles/543dae5d2825ee

Here is a test with \set AUTOCOMMIT off:

-- create a test database

$ createdb test1

-- dump all databases to an SQL script file

-- -c issues DROP for databases, roles, and tablespaces before recreating them

$ pg_dumpall -c -f test1.sql

-- restore with psql

$ psql -f test1.sql

~snip~

psql:test1.sql:14: ERROR: DROP DATABASE cannot run inside a transaction block

psql:test1.sql:23: ERROR: current transaction is aborted, commands ignored until end of transaction block

psql:test1.sql:30: ERROR: current transaction is aborted, commands ignored until end of transaction block

psql:test1.sql:31: ERROR: current transaction is aborted, commands ignored until end of transaction block

~snip~

DROP DATABASE from -c cannot run inside a transaction block, so you get these errors. Also, by default, when a statement fails inside a transaction block, the whole transaction aborts, so later statem

Unpublished interview

Posted by Oleg Bartunov in Postgres Professional on 2025-12-23 at 12:54

Interview with Oleg Bartunov

“Making Postgres available in multiple languages was not my goal—I was just working on my actual task.”

Oleg Bartunov has been involved in PostgreSQL development for over 20 years. He was the first person to introduce locale support, worked on non-atomic data types in this popular DBMS, and improved a number of index access methods. He is also known as a Himalayan traveler, astronomer, and photographer.

— Many of your colleagues know you as a member of the PostgreSQL Global Development Group. How did you get started with Postgres? When and why did you join the PostgreSQL community?

— My scientific interests led me to the PostgreSQL community in the early 1990s. I’m a professional astronomer, and astronomy is the science of data. At first, I wrote databases myself for my specific tasks. Then I went to the United States—in California, I learned that ready-made databases existed, including open-source ones you could just take and use for free! At the University of Berkeley, I encountered a system suited to my needs. At that time, it was still Ingres, not even Postgres95 yet. Back then, the future PostgreSQL DBMS didn’t have many users—the entire mailing list consisted of 400 people, including me. Those were happy times.

— Does your experience as a PostgreSQL developer help you contribute to astronomy?

— We’ve done a lot for astronomy. Astronomical objects are objects on a sphere, so they have spherical coordinates. We introduced several specialized data types for astronomers and implemented full support for them—on par with numbers and strings.

— How did scientific tasks transform into business ones?

— I started using PostgreSQL to solve my astronomical problems. Gradually, people from outside my field began reaching out to me. In 1994, it became necessary to create a digital archive for The Teacher’s Newspaper, an

Don't give Postgres too much memory (even on busy systems)

Posted by Tomas Vondra on 2025-12-23 at 10:00

A couple weeks ago I posted about how setting maintenance_work_mem too high may make things slower. Which can be surprising, as the intuition is that memory makes things faster. I got an e-mail about that post, asking if the conclusion would change on a busy system. That’s a really good question, so let’s look at it.

To paraphrase the message I got, it went something like this:

Lower

maintenance_work_mem valuesmay split the task into chunks that fit into the CPU cache. Which may end up being faster than with larger chunks.

PostgreSQL Santa’s Naughty Query List: How to Earn a Spot on the Nice Query List?

Posted by Mayur B. on 2025-12-23 at 07:01

Santa doesn’t judge your SQL by intent. Santa judges it by execution plans, logical io, cpu utilization, temp usage, and response time.

This is a practical conversion guide: common “naughty” query patterns and the simplest ways to turn each into a “nice list” version that is faster, more predictable, and less likely to ruin your on-call holidays.

1) Naughty: SELECT * on wide tables (~100 columns)

Why it’s naughty

- Wider tuples cost more everywhere: more memory bandwidth, more cache misses, bigger sort/hash entries, more network payload.

- Index-only becomes impossible: if you request 100 columns, the planner can’t satisfy the query from a narrow index, so you force heap fetches.

- You pay a bigger “spill tax”: wide rows make sorts/aggregations spill to disk sooner.

Extra naughty in the HTAP era

Postgres is increasingly “one database, multiple workloads.” Columnar/analytics options (e.g., Orioledb, Hydra Columnar; DuckDB-backed columnstore/engine integrations) make projection discipline even more decisive, because columnar execution reads only the referenced columns so selecting fewer columns directly reduces I/O and CPU.

Nice list fixes

- Always select only what you need.

Santa verdict: If you didn’t need the column, don’t fetch it, don’t carry it, don’t ship it.

2) Naughty: WHERE tenant_id = $1 ... ORDER BY x LIMIT N that hits the “ORDER BY + LIMIT optimizer quirk”

Why it’s naughty

This is a classic planner trap: the optimizer tries to be clever and exploit an index that matches ORDER BY, so it can stop early with LIMIT. But if the filtering predicate is satisfied “elsewhere” (joins, correlations, distribution skew), Postgres may end up scanning far more rows than expected before it finds the first N that qualify. That’s the performance cliff.

PostgreSQL Performance: Latency in the Cloud and On Premise

Posted by Hans-Juergen Schoenig in Cybertec on 2025-12-23 at 05:00

PostgreSQL is highly suitable for powering critical applications in all industries. While PostgreSQL offers good performance, there are issues not too many users are aware of but which play a key role when it comes to efficiency and speed in general. Most people understand that more CPUs, better storage, more RAM and alike will speed up things. But what about something that is equally important?

We are of course talking about “latency”.

What does latency mean and why does it matter?

The time a database needs to execute a query is only a fraction of the time the application needs to actually receive an answer. The following image shows why:

When the client application sends a request, it will ask the driver to send a message over the wire to PostgreSQL (a), which then executes the query (b) and sends the result set back to the application (c). The core question now is: Are (a) and (c) relative to (b) relevant? Let us find out and see. First, we will initialize a simple test database with pgbench. For the sake of this test, a small database is totally sufficient:

cybertec$ pgbench -i blog

dropping old tables...

NOTICE: table "pgbench_accounts" does not exist, skipping

NOTICE: table "pgbench_branches" does not exist, skipping

NOTICE: table "pgbench_history" does not exist, skipping

NOTICE: table "pgbench_tellers" does not exist, skipping

creating tables...

generating data (client-side)...

vacuuming...

creating primary keys...

done in 0.19 s (drop tables 0.00 s, create tables 0.02 s, client-side generate 0.13 s, vacuum 0.02 s, primary keys 0.02 s).

Now, let us run a first simple test. What it does is to start a single UNIX socket connection and just run for 20 seconds (a read-only test):

cybertec$ pgbench -c 1 -T 20 -S blog

pgbench (17.5)

starting vacuum...end.

transaction type:

scaling factor: 1

query mode: simple

number of clients: 1

number of threads: 1

maximum number of tri Instant database clones with PostgreSQL 18

Posted by Radim Marek on 2025-12-22 at 23:30

Have you ever watched long running migration script, wondering if it's about to wreck your data? Or wish you can "just" spin a fresh copy of database for each test run? Or wanted to have reproducible snapshots to reset between runs of your test suite, (and yes, because you are reading boringSQL) needed to reset the learning environment?

When your database is a few megabytes, pg_dump and restore works fine. But what happens when you're dealing with hundreds of megabytes/gigabytes - or more? Suddenly "just make a copy" becomes a burden.

You've probably noticed that PostgreSQL connects to template1 by default. What you might have missed is that there's a whole templating system hiding in plain sight. Every time you run

CREATE DATABASE dbname;

PostgreSQL quietly clones standard system database template1 behind the scenes. Making it same as if you would use

CREATE DATABASE dbname TEMPLATE template1;

The real power comes from the fact that you can replace template1 with any database. You can find more at Template Database documentation.

In this article, we will cover a few tweaks that turn this templating system into an instant, zero-copy database cloning machine.

CREATE DATABASE ... STRATEGY

Before PostgreSQL 15, when you created a new database from a template, it operated strictly on the file level. This was effective, but to make it reliable, Postgres had to flush all pending operations to disk (using CHECKPOINT) before taking a consistent snapshot. This created a massive I/O spike - a "Checkpoint Storm" - that could stall your production traffic.

Version 15 of PostgreSQL introduced new parameter CREATE DATABASE ... STRATEGY = [strategy] and at the same time changed the default behaviour how the new databases are created from templates. The new default become WAL_LOG which copies block-by-block via the Write-Ahead Log (WAL), making I/O sequential (and much smoother) and support for concurrency without facing latency spike. This prevented the need to CHECKPOINT but made the databa

Contributions for week 52, 2025

Posted by Cornelia Biacsics in postgres-contrib.org on 2025-12-22 at 19:08

Pavlo Golub gave a talk at WaW Tech conference in Warsaw on Dec 16 2025

Hyderabad PostgreSQL UserGroup Meetup on Dec 19 2025. Organised by Hari Kiran.

Speakers:

- Shameer Bhupathi

- Jagadish Kantubugata

- Jeevan DC

- Uma Shankar PB

- Uttam Samudrala

The PostgreSQL User Group meeting in Islamabad wasn’t mentioned earlier. The meetup took place on December 6 and was organized by Umair Shahid, who also gave a talk at the event.

Community Blog Posts

-

Andreas Scherbaum Berlin November 2025 Meetup

-

Valeria Kaplan From PGDays to PGCon/fs

-

Cornelia Biacsics Eye Strain, Podcasts and Gratitude

Top posters

Number of posts in the past two months

Cornelia Biacsics (postgres-contrib.org) - 7

Cornelia Biacsics (postgres-contrib.org) - 7 Ian Barwick - 6

Ian Barwick - 6 Floor Drees (EDB) - 6

Floor Drees (EDB) - 6 Hubert 'depesz' Lubaczewski - 6

Hubert 'depesz' Lubaczewski - 6 Hans-Juergen Schoenig (Cybertec) - 5

Hans-Juergen Schoenig (Cybertec) - 5 Dave Page (pgEdge) - 5

Dave Page (pgEdge) - 5 Robins Tharakan - 5

Robins Tharakan - 5 Ahsan Hadi (pgEdge) - 4

Ahsan Hadi (pgEdge) - 4 Josef Machytka (credativ) - 4

Josef Machytka (credativ) - 4 Bruce Momjian (EDB) - 4

Bruce Momjian (EDB) - 4

Top teams

Number of posts in the past two months

- EDB - 20

- pgEdge - 16

- Cybertec - 13

- postgres-contrib.org - 9

- Data Bene - 7

- Percona - 6

- Crunchy Data - 6

- Stormatics - 5

- credativ - 4

- Data Egret - 4

Feeds

Planet

- Policy for being listed on Planet PostgreSQL.

- Add your blog to Planet PostgreSQL.

- List of all subscribed blogs.

- Manage your registration.

Contact

Get in touch with the Planet PostgreSQL administrators at planet at postgresql.org.