Previously: Subobject Classifier.

In category theory, objects are devoid of internal structure. We’ve seen however that in certain categories we can define relationships between objects that mimic the set-theoretic idea of one set being the subset of another. We do this using the subobject classifier.

We would like to define a subobject classifier in the category of presheaves, so we could easily characterize subfunctors of a given presheaf. This will help us work with sieves, which are subfunctors of the hom-functor ; and coverages, which are special kinds of sieves.

Recall that a presheaf is a subfunctor of another presheaf

if it satisfies two conditions.

- For every object

, we have a set inclusion:

,

- For every morphism

, the function

is a restriction of the function

. In other words,

and

must agree on the subset

.

As category theory goes, this is a very low-level definition. We need something more abstract: We need to construct a subobject classifier in the category of presheaves. Recall that a subobject classifier is defined by the following pullback diagram:

This time, however, the objects are presheaves and the arrows are natural transformations.

To begin with we have to define a terminal presheaf, that satisfies the condition that, for any presheaf

, there is a unique natural transformation

. This will work if every component

of this natural transformation is unique, which is true if we choose

to be the terminal singleton set

. Thus the terminal presheaf maps all objects to the terminal set, and all morphisms to the identity on

.

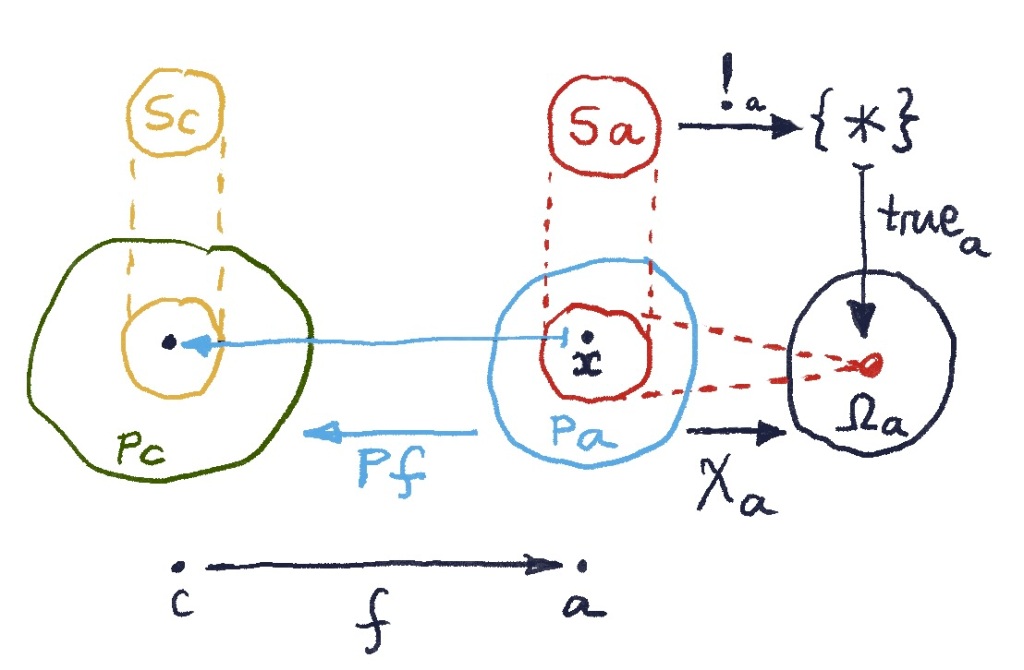

Next, let’s instantiate the subobject classifier diagram at a particular object .

Here, the component picks a special “True” element in the set

. If the presheaf

is a subfunctor of

, the set

is a subset of

. The function

must therefore map the whole subset

to “True”. This is consistent with our definition of the subobject classifier for sets.

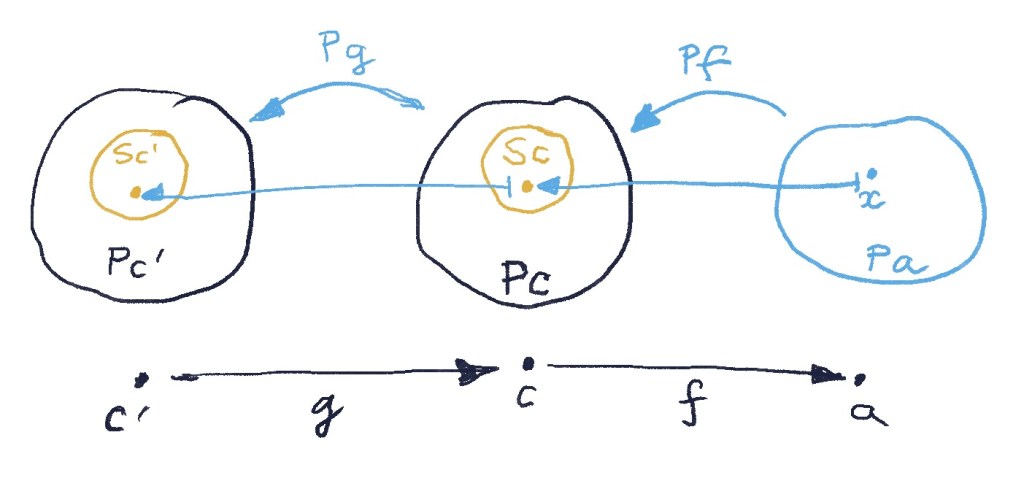

The second condition in the definition of a subfunctor is more interesting. It involves the mapping of morphisms.

The restriction condition

We have to consider all morphisms converging on our object of interest . For instance, lets take

. The presheaf

lifts it to a function

. If

is a subfunctor of

,

is a restriction of

.

Specifically the restriction condition tells us that, if we pick an element , then both

and

will map it to the same element of

. In fact, when defining a subobject, we only care if the embedding of

in

is injective (monomorphic). It’s okay if it permutes the elements of

. So it’s enough that, for all

, the following condition is satisfied:

Now consider an arbitrary (not necessarily an element of

). We can gather all arrows

converging on

for which the subset-mapping condition is satisfied:

If is a subfunctor of

, these arrows form a sieve on

, as any composition

also satisfies the subset-mapping condition:

Moreover, if is in fact an element of

, this sieve is the maximal sieve. A maximal sieve on

is a collection of all arrows converging on

.

We can now define a function that assigns to each

the sieve of arrows that satisfy the subset-mapping condition.

The function has the property that, if

is an element of

, the result is the maximal sieve on

.

It makes sense then to define as a set of sieves on

, and “True” as the maximal sieve on

. (Thus

is a set whose elements are sets.)

The mapping can be made into a presheaf by defining its action on morphisms. The lifting of

takes a sieve

to a sieve

, defined as a set of arrows

, such that

.

Notice that the resulting sieve is maximal if and only if

. (Hint: If a sieve is maximal, then it contains identity.)

It can be shown that the the functions combine to form a natural transformation

.

What remains to be shown is that this is a unique such natural transformation that completes the pullback:

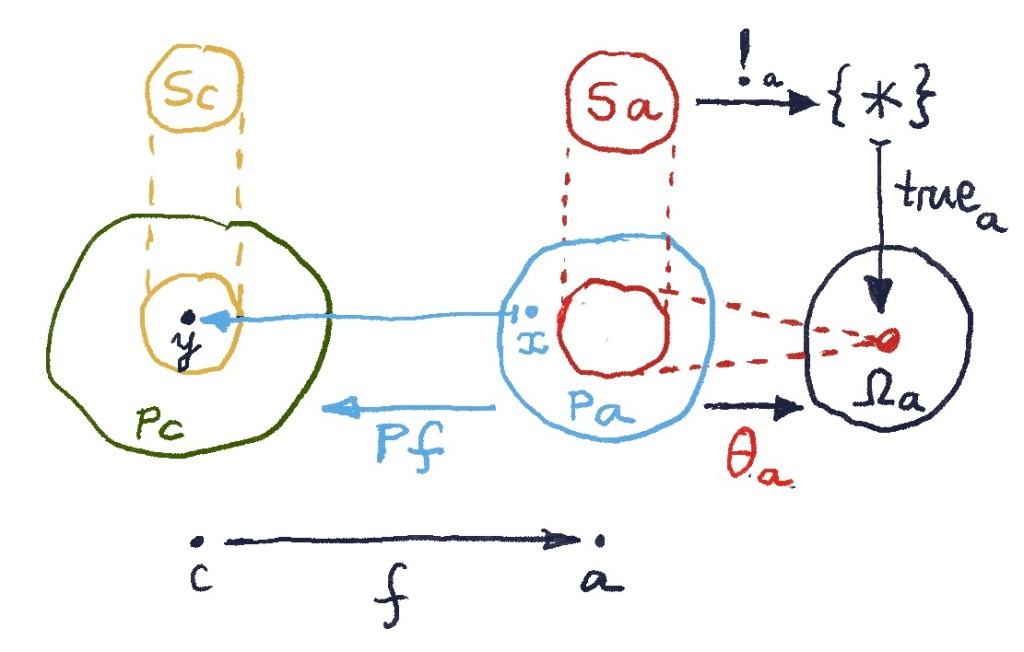

To show that, let’s assume that there is another natural transformation making this diagram into a pullback. Let’s redraw the subfunctor condition for arrows, replacing

with

:

Let’s pick an and call

. We’ll follow a set of equivalences.

The pullback condition:

tells us that is equivalent to

. In other words:

Using naturality of :

we can rewrite it as:

.

Both sides of this equation are sieves. By definition, the lifting of ,

, acting on

is a sieve defined by the following set of arrows:

Since is a maximal sieve, it must be that

.

We have shown that the condition is equivalent to

. But the first condition is exactly the one we used to define

. Therefore

is the only function that makes the subobject classifier diagram into a pullback.

Subfunctor classifier

The subobject classifier in the category of presheaves is thus a presheaf that maps objects to sieves, together with the natural transformation

that picks maximal sieves.

Every natural transformation defines a subfunctor of the presheaf

. The components of this natural transformation serve as characteristic functions for the sets

. A given element

is in the subset

iff

maps it to the maximal sieve on

.

But there’s not one but many different ways of failing the subset test. They are given by non-maximal sieves. We may think of them as satisfying the Anna Karenina principle, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Why sieves? Because once an element of a set is mapped by

to an element of a subset

, it will continue to be mapped into consecutive subsets

, etc. The network of “happy” morphisms keeps growing outward. By contrast, the “unhappy” elements of

have at least one morphism

, whose lifting maps it outside the subset

. That’s the morphism that’s absent from the non-maximal sieve

. Finally, naturality of

ensures that subset conditions propagate coherently from object to object.

Next: Fibrations and Cofibrations.