Something in the Water

These fragments are all culled from a larger piece of work about beer, family, place and memory that is still fermenting somewhere in my head. I was inspired to finally put out a flight of snippets in response to Boak & Bailey’s #BeeryLongReads2020 challenge

* * *

Say, for what were hop-yards meant,

Or why was Burton built on Trent?

Oh many a peer of England brews

Livelier liquor than the Muse,

And malt does more than Milton can

To justify God’s ways to man.

A.E. Housman, A Shropshire Lad

* * *

The first sip of a pint of ale made in Burton upon Trent can be off-putting to a newcomer. There’s something intangibly difficult about it, a shrugging note of unpleasantness that many find unsettling - a mineral toned, brackish kind of scent, that most immediately brings to mind sulphur; that distinct, diffuse, almost rotten egg character that you find in the water of towns that marketed themselves as spas, and once sold their healing properties to gullible Victorians with chronic nerve conditions.

Connoisseurs have a name for it, likening it to the fleeting sensory overload of an old-fashioned match being struck in a dark, draughty room.

They call it “The Burton Snatch”.

* * *

My father’s family have always lived in Burton and its surrounding villages, nestled among the hills and valleys between Staffordshire and Derbyshire. My great-grandfather was a farmer and a money-lender, who kept a cast iron safe in the living room with a lace doily and a bowl of fruit on top. He would open it up on Sunday evenings to take stock, counting out the large paper notes on his scrubbed wooden table while the rest of the family looked on.

My grandfather, Jimmy, was a promising football player who did a stint with Burton Albion, before going into business in the town, setting up Farrington’s Furnishers in two large units on the Horninglow Road. It was the kind of traditional, rambling shop that doesn’t exist much anymore - a haphazardly laid-out assembly of sofas, beds, dressers and wardrobes, tables, chairs, footstools and chests of drawers. At the back, there was a room full of rolls of carpet, piled high to the ceiling. My father and his brothers were playing there when the news came over the radio that JFK had been shot.

* * *

Brewing has happened in Burton for centuries, but the process really began millennia ago, when the substrata of the Trent valley settled with deep deposits of sand and gravel, a unique and serendipitous combination of minerals that built the foundations for everything that was to follow. An unusually high concentration of sulphates from the gypsum, coupled with healthy reserves of calcium and magnesium and low levels of sodium and bicarbonates, meant that when springs eventually burbled forth from the land around the river, the water had its own particular and unique character, a distinct presentation that the French might call “terroir”.

Beer-making started in earnest when an abbey named Byrtune was raised on the banks of the Trent, and the brothers did as all good monastic orders did, growing their own crops, raising their own livestock, and brewing their own beer. Over the centuries, the reputation for the region’s fine ale grew and spread, until the secret could no longer be kept.

When the canals came to Burton they made it into a city of industry and empire. Tentacle-like, capitalism stretched and unfurled its penetrating waterways across, through and over Albion’s gentle hills, bypassing the wild weirs of the Trent’s natural descent, domesticating the landscape and bringing uniformity, neatness, and standardisation to what was a tangle of disparate places and processes. By the middle of the 18th century, the Trent Navigation had been connected to the Humber, to the mighty Mersey, and down through Birmingham to the Grand Union, and suddenly, Burton was now a central hub functioning as part of a single network that ran throughout the country and onward, through its bustling ports, to Europe, Russia, and all points beyond.

* * *

Once their children grew up, my grandparents also left for the continent. Nearly every summer holiday of my childhood was spent visiting them in Portugal. Their home, known only as “The Villa”, was an idyllic place, where my brothers and I learnt to swim, where the smell of barbecue smoke lingered over every evening, where the coarse Mediterranean grass hurt our feet when we tried to play football on it. When I was young, I only really knew my grandparents in this sunlit, bright blue light - tanned, shortsleeved, wearing hats. Their accents may have been rounded and roughened in the heart of England, but their very essence to me was more exotic, more glamorous, more European.

Some of my first memories of drinking come from those summer holidays. Sips of pungent sea-dark wine, acidic and overwhelming; a sample of gin and tonic, bitter and medicinal with a gasping clarity; and of course, beer - not ale, nothing my grandfather would touch - but lager, cold and crisp and gassy, a fleeting glimpse of adulthood.

* * *

Beer, like everything else in a free market of money and ideas, has been subject to fashion and changing tastes, and it was a fashion for pale ales that truly put Burton on the map. With the proliferation of the waterways, hops from Kent and barley from East Anglia could make their way to Burton where, combined with the local water, they were turned into a revelatory, and wildly popular beverage.

Breweries proliferated throughout the town. At its peak, more than 30 rival businesses competed for space, ingredients, and workers to keep the kettles boiling and grain mashing. Burton became the brewing capital of the world, home to emblematic firms like Bass, which by 1877 was the world’s largest brewery. Its famed pale ale was so acclaimed and copied that the distinctive red triangle that adorned its labels became the UK’s first registered trademark, a mark of its singular quality.

* * *

Even when my grandparents lived abroad, Burton still pulled my family to it. Christmas called us back year after year, or Boxing Day at least, catching up with uncles and aunts and first and second cousins, some removed, to sit in sitting rooms in front of three-bar fires, eating ham cobs, drinking flat Schweppes lemonade, watching World’s Strongest Man on the television. The arresting vision of a large man pulling a tractor down a runway or throwing a washing machine over a wall would be accompanied by the sound of adult chatter, long-delayed catch-ups on weddings, births, and especially deaths - distant relatives and long-lost school mates, old girlfriends with cancer scares, run-ins with the police.

One uncle, who worked in a brewery like a true Burtonian, kept terrapins. I would gingerly feed them sunflower seeds, holding my hand above the dark waterline of the cramped tank, waiting for the vicious snap to emerge from the depths. “Pedigree doesn’t travel well,” he once told me, referring to a renowned local bitter. Some things cannot leave Burton behind.

* * *

Burton’s skyline doesn’t have church towers, it has fermentation vessels. Over the decades, as companies have merged, collapsed, consolidated or been taken over with some hostility, the name on the side of the largest set has changed, so that what drivers on the bypass see reflects whatever corporate overlord assumes feudal control in that particular age.

In the middle years of the twentieth century, brewing, like many industries, saw the white hot intensity of competition eliminate all but the largest of breweries. Experts will tell you that the beer suffered along with it, accompanied by punitive taxation from the government and a nannying attitude to pubs and drinking, the hangover of Victorian prudishness being enacted by the grandchildren of those who first envisaged it. Tastes changed under the weight of global pressures, and ultimately, Burton lurched along with them, becoming, through a complex web of corporate exchanges, the brewing site of Canadian brand Carling Black Label.

In the ensuing decades, Carling would become the UK’s best-selling beer, a “domestic” rival to the traditional European lager brands that dominated in Germany, France and Denmark. The attritional battles left their marks on Burton though, as closures and collisions shuttered various facilities and churned through generations of workers, leaving tracts of vacant space even in the centre of town. Coming off the train now, you overlook the whole of Burton, and get the sensation of standing in the middle of a vast and scattered industrial facility, where smokestacks and grain towers overpeer gritted-teeth terraced houses, pockmarked shopping streets and vacant lots.

The make-up of the town shifted too. In the middle of the Midlands (Burton is linguistically and administratively part of the East Midlands, but geographically in the West Midlands) the town received its fair share of immigration. A town my grandparents knew as almost entirely white and Christian is now almost 10% Pakistani Muslim - a thriving community of teetotallers, in a town famous for its beer.

* * *

My grandparents celebrated their diamond wedding anniversary in 2014, flying back from Portugal to hold a party at the National Brewery Centre in the middle of Burton. It was a lovely evening, with a large cake and lots of happy stories, relatives and friends I’d never seen before and would never see again. After an early finish, my cousins and I went to a pub, drinking pints of milk-smooth ale, before ending up in a small, loud, nightclub playing cheesy pop hits. The next morning, hungover, I walked with my parents to Stapenhill Cemetery to stare at the headstones of ancestors I had never met.

* * *

There is a popular documentary series on the BBC which sees celebrity costermonger Gregg Wallace visit various sterile facilities around the UK to witness firsthand how automation and mechanisation has changed food production. Each episode has him walking through eerily empty factories, vast and cavernous spaces where robotic production lines operate 24 hours a day, speaking to the remaining human operators who exist now as mere caretakers, there to tend and nurse the machines like temple virgins, dressed in hairnets instead of togas. It is an uncanny sight. Every installment inevitably begins with drone shots, hovering silently above the landscape, showing the immense scale of these conurbations, raised in places where land is invariably cheap and generations of people have been bred into cycles of tireless shift work. But the workers are not needed any more. Efficiency has eradicated the need for fleshy points of failure.

Now, Gregg can skip through the barren hallways, silent save for the harmonic hum of perpetual machinery, flashing his blinding white overalls and quoting mind-boggling statistics about the weight of crisps the average British child eats in a year. Various natural products are ushered in off the backs of lorries and railway carriages, fed along whirring conveyor belts and pumped through pneumatic tubes, before being baked, frozen, cut, dried, soaked, dessicated, rehydrated and reformulated into whatever bland final product can now be ejected out into the world, via shipping containers and along motorways, all to sit on a supermarket shelf before making an appearance in your cupboard, a moment on your table, and a lifetime rotting away in some far-off landfill.

It was inevitable that Burton’s MolsonCoors brewery, the home of Carling, would get its chance in the spotlight. The programme highlighted the noble history of brewing, from its pre-modern farmhouse days, when fermentation was practically a shamanic ritual, to its domestication and commodification, where each step in the process was refined and perfected, to where we are now, when every aspect has been exactingly costed and painstakingly budgeted to ensure maximum productivity, and maximum profit, with minimal ingredients, energy, or intervention. There has been a backlash to this macro-attitude, of course - “craft beer”, an ill-defined, equally co-optable movement that alludes to provenance, quality, care, and a confused sense of heritage, has become a big business in its own right, backed by venture capital and crowdfunding campaigns - but industrial brewing is still the fixture in the firmament, the thing that keeps the lights on.

When one of the few remaining humans showed Gregg the tiny, almost homeopathic quantity of hops that would add a semblance of bitterness and aromatic flavour to a lake-sized vat of Carling, it felt almost like a knowing wink - look at what we can get away with - one made safe in the knowledge that their beer will still pour in nearly every pub and take up the most shelf space in corner shops and petrol stations across the country. Of course they’ll get away with it. They’ve always got away with it. They will sell us beer with barely a sense memory of taste in it, and we will literally lap it up.

* * *

My grandfather died in hospital, in Portugal, after an indeterminate period of undramatic but gradually worsening health. His four children took turns flying out to spend time with him and their mother in the hospital, sitting by his bed, holding his hand, finishing the crosswords he was no longer able to complete.

He was cremated there, but a memorial service to remember his life was held in Burton on a crisp, February day a few weeks later. Alighting at the railway station, I watched steam from the breweries crowd the startlingly cold air, while waiting for my parents to arrive and drive us the ten minutes to Rolleston Cricket Club where the small gathering would take place. On the way, we drove up Horninglow Road, past what was once Farrington’s Furnishers, now Zielona Żabkal, a Polish supermarket. We got there early and spent some time setting up, arranging the folding tables and stackable chairs, hanging up photos, and laying out some mementos of my grandfather’s happy life - a table tennis bat, some puzzle books, a golf club, his familiar white hat.

I was tasked with approving the beer for the day. There were two casks of Bass on the bar - one which had been there a few days, the other tapped that morning. “I’m a lager man,” the bartender told me, so I tried both to see which was in form. The first had the faintest tang of vinegar that suggested oxidation, a beer that was at the end of its life, drowning in the air around it. The second was lively, enthusiastic, a little overly keen and overripe, but would settle down through the afternoon as the long goose-necked pump poured pint after pint for the guests who shuffled in, in suits and raincoats, shiny shoes and walking sticks, to pay their respects. Everyone told stories. I read a letter on behalf of my cousin, working on the other side of the world. We drank many, many pints of Bass in good nick, then when we were finished, we went to a pub, and drank many more.

When I had to catch my train back to London, I staggered back through the freezing night, to find that the town was mashing in - somewhere in the vast floodlit breweries, a switch had been thrown and malted barley was being soaked in that famous hot water, and the streets were being filled with the scent of porridge and healthy, earthy grains; a warming, nostalgic tide that overflowed down the road and spilled through the centuries; riding, falling, on the biting cold air.

A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Almost Certainly Do Again

A lot of people die on cruise ships.

Some - a worryingly large number in fact - fall overboard, though this is a relatively rare occurrence in the grand scheme of things. A few will suffer freak accidents. Then there are those that just disappear, into the gap left by millions of square miles of desolate ocean and the vagaries of international maritime law.

But most just die of natural causes. A lot of people who go on cruises are old, and many aren’t in particularly good health. Give them an extended period of overindulgence and a melting-pot of germs, and it’s only natural that some will go out in style. Every cruise ship has a morgue tucked away on the lower decks, somewhere between the laundry rooms and the mighty engines.

A lot of it will be down to booze. People really go for it on cruises. Most operators offer all-inclusive drinks deals, which, given the price tag, only encourage you to push the envelope (given the price, you generally have to drink at least eight to 10 drinks a day to make it value for money, if not more). Nearly every cruise ship has a plethora of drinking establishments - pool bars, piano bars, ersatz pubs, cocktails joints, people who come around to your lounger and offer you drinks, 24-hour room service. There are plenty of passengers who step off dry land and don’t get dry again until they leave. And why would you? You’re on holiday. Treat yourself.

So how does that square with Disney and their family friendly, squeaky-clean public image? You never see Mickey looking half-cut. In fact, Disney doesn’t even offer drinks packages on its cruise ships. But I didn’t let that stop me.

In fact, almost as soon as I boarded the Disney Magic on sun-blasted Miami morning in December, I was thinking about beer. My wife had joined a Facebook drink dedicated to our sailing, and found an old hand who organised a beer swap event for every voyage he was on (this was his tenth, as it turned out. Disney fans are nothing if not loyal). Disney’s policy lets you bring six beers on board for personal consumption, but the swap event encouraged you to share your haul on a table in the night club, then take it in turns to draft a new six-pack from the combined spoils. With most people bringing stuff that was local to them, it actually turned out to be a great way to sample new things - I took a bunch of Due South Caramel Cream Ale (a Florida brewery’s eyebrow-raising flagship) and came back with cans from Modern Times, New Belgium, Odell and Avery - a haul I couldn’t help but be impressed by.

In fact, despite the abstemious impression the House of Mouse gives off, there was better beer on the boat that initially met the eye. While the main bars offered beers for every taste - Bud Lite OR Miller Lite - the “Irish” pub, O’Gills, where I hung out to watch a disappointing NFL game, actually had an impressive list for a venue floating somewhere south of Cuba- Orval, Ayinger Celebrator and Saison Dupont to name a few.

I also had my reserve stash - ie, the six-pack my wife was allowed to bring on board, but had kindly gifted to me. The issue was when and how to drink it. Feeling self-conscious - and somewhat gauche - about glugging from a bottle of Dogfish Head BA Worldwide Stout, I found that the ideal solution was to decant it (let it breathe, if you will), into a styrofoam coffee cup, lid optional, or else the plastic cup that my daughter’s apple juice was served in at dinner. In that way, I was happy to pass the time on deck, lounging by the pool and watching whichever Disney classic they played on the big screen (a grim reminder of how many shipwrecks there are in Disney films), or indeed, in the cruise ship’s own cinema, enjoying a New Holland Dragon’s Milk while rolling my eyes at the Rise of Skywalker.

On shore, the options were a bit less intriguing. Apparently there is a “craft” brewery on Grand Cayman, but the only beer I ended up with on the island was Caybrew, the local lager, a musty, sweaty, earthy beer notable for its distinct lack of refreshment on a sweltering Caribbean day. On Castaway Cay - Disney’s private island, a former drug baron’s hideout that has been sanitised and dynamited by the corporation into a tranquil, tropical resort, the only options are macro lagers and gaudy cocktails with fruit and parasols and terrible pun names. If you want to drink good beer, you have to provide it yourself, but at least they let you.

David Foster Wallace famously decided that cruise life probably wasn’t for him, but he never had imperial stouts. He also didn’t have Goofy doing laps of the promenade deck in jogging gear, or a party night themed around pirates (which seemed in very bad taste - pirates are the natural enemies of sailors. It’s like mice having a cat party). Perhaps he would have thought differently if Rapunzel had serenaded him during dinner.

As for me, I’m already planning out my six pack for the next cruise. Some heavy stouts, some supercharged IPAs. Lots of flavour, lots of booze, but nothing too outrageous. I want them to be strong, but I don’t want to go overboard.

Well-known Pleasures

I used to drink a lot of Boddingtons at university, and I have no idea why.

I drank a lot at university generally. It was where I went to my first ale festival and fell in love with beer, but it went beyond that. I drank a lot of red wine at the formal dinners that made up a regular part of Cambridge social life (typically everyone would have got through a bottle each by the time starters were finished, thanks to the stupid habit of throwing pennies in each other’s glasses - a challenge to down it that couldn’t be refused - forcing a run to the bar as soon as dessert was done). I drank a lot of white wine at smart events like poetry readings and debate nights (societies were only allowed to supply white - red posed too much of a risk to carpets). I drank port for the first time, an acquaintance I was happy to make and have remained familiar with. I drank a curious concoction called Trinity Blue at all the terrible termly “bops” - vodka, Archers, blue curacao and lemonade is my dim memory of the ingredients, though you would typically remember very little the morning after. In short, I drank everything that came my way, and for reasons unknown, that included Boddingtons.

It may have been that it was on sale in college. As well as the bar, there was the buttery, a kind of booze-led tuck shop that mainly supplied reasonably priced wine for formals (it is said Trinity has some of the finest wine cellars in the country, though I’ve since seen most of the selections in Waitrose), but also did beer - Budvar, for sure, and Boddingtons, possibly. The main appeal of this was that you could charge it to your college card and deal with the actual bill at the end of term, which of course meant I used it most days. Free beer! Who could resist?

It’s not even like Boddingtons was a popular beer back then. It was many years removed from the popular Melanie Sykes adverts that branded it the “cream of Manchester”, and some time after the famous adverts featuring the cartoon cow - a male cow, somehow - udders swinging free, hanging out in nightclubs and supping pints. It was even years after it was namechecked, bizarrely, in an episode of Friends, as a highlight of Joey and Chandler’s trip to the UK. Boddingtons is even less popular now - no cows, no Mancunian models, no national ad campaign at all, and on sale in my local Co-op for £3 for a four-pack. So I had to revisit it.

I wondered once why the UK didn’t seem to have an equivalent of National Bohemian, or Narragansett, or Genesee, or Hamm’s - regional lager brands that are local, cheap, and deeply held in people’s affections. Britain has never been a lager nation in the same way, so if we did have our own version, it would have to be an ale, and I wonder if something like Boddingtons might come closest. It’s demonstrably cheap, has a deep sense of place, and the kind of memorable, if vintage branding that gives drinkers a nostalgic fondness for it.

The other thing those American beers have in common is their flavour, or lack of it - they’re straightforward, crisp, satisfying lagers - unchallenging, indistinct, but enough. Boddingtons is different though. I always used to think there was a slight honey sweetness to it, though now I wonder if that was just a weird sense association thanks to the bees on the can. Now I find more of an earthy dryness that I would associate with a Manchester bitter, but also flavours that seem out of place if not flat out wrong - a tinge of banana, a metallic edge - signs of a product that seems somewhat tired and unloved. The whole thing is served with that mini miracle of modern engineering, a widget, flooding the beer with nitrogen and giving it the milky softness that earned it the cream of Manchester tag in the first place, and giving it that tight cuff of off-white head that is undeniably inviting. It’s old school. It’s unfashionable. It’s not great. But it’s also somehow slightly comforting and not entirely unpleasant. The four cans are a fine nostalgia trip, and all for cheaper than most bus tickets.

I learned a lot at university - literary theory, reams of Shakespeare, basic Italian - all things I’ve mostly forgotten. But when facts go, tastes remain. And nostalgia is the sweetest of flavour of all.

Arm in Arm

In Cardiff, on Westgate Street, there are two pubs that are, given good technique and a fair wind, literally spitting distance from each other. And yet, despite their physical proximity, it sometimes feels like they couldn’t be further apart.

One pub, Tiny Rebel Cardiff, is the expansive taproom of the popular Welsh brewery. Built in the modern craft beer vernacular - exposed brickwork, band posters, giant TV screens with up-to-the-minute taplists - there’s an accompanying food menu which is a teenager’s fever dream of American diner classics (the pork belly burger was incredible), while it also plays host to gigs and comedy sets as well as slinging pastry stouts and hazy IPAs.

Over the road is the City Arms. A de facto tap for the venerable Brains brewery, it’s a wood-panelled, sticky-tabelled kind of joint, with pump clips above the picture rail and a mix of old black and white photos and cartoons of dubious political correctness on the walls. The beer list here is almost as comprehensive as its neighbour, but with a focus on cask, particularly Brains classics like SA and Revered James.

I stopped into both last Sunday, a strange morning to be in Wales, where the Rugby World Cup loss had left a mild pall in the mid-morning air, offset only by the startlingly sun-filled October sky. In the City Arms, I ordered a pint of SA, a perfect Malted Milk biscuit of a pint, served via a sparkler - proof, if it were ever needed, that Wales is spiritually Northern (I will die on the hill that the dividing line runs from the Severn Estuary to the Wash). With bright blue light steaming in the condensation-fogged windows, and men in red shirts already struggling to keep balance alongside the well-scrubbed bar, it was a moment of such striking clarity, such simple pleasure, that I wondered why I ever bothered drinking anywhere else. Yes, there’s the small matter of living 200 miles away, but a good pint of bitter - one that makes you instinctively go “Ooh, that’s good” after the first swallow - is a remarkably persuasive thing.

Over in Tiny Rebel, I wanted to try as much as possible, and I did - a passable lager with a disconcerting peanut note, an opaque pale ale with an acerbic citrus edge, a synthetically sweet imperial stout. There was nothing necessarily wrong with these beers - and they were obviously popular with the crowded lunchtime tables - but each one left me thinking about the bitter over the road, the trad ale I’d drunk so thoughtlessly as a teenager and neglected for so long.

Am I getting old? Am I just being contrary, or needlessly nostalgic? Was I just seduced by a shaft of sunlight and a familiar flavour? Is it just because the City Arms is name-checked by my favourite band?* I think it’s all of these things. The shock of the new is beginning to wear thin - now I’m digging deep in the back of the cupboard for thick, cable-knit sweaters, the kind that can keep you warm in any weather and last a lifetime along the way.

And yet, I’m glad that these two places can co-exist, offering different things to different people, but both showing the range and the moods of beer today. They’re not necessarily opposites, they complement as much as contrast.

They take turns living in the other’s shadow, depending on the time of day.

*Baby I Got the Death Rattle by Los Campesinos!

A Swift Half

“I never stopped loving you” reads Tracey Emin’s semi-legible, always familiar neon scrawl across the face of Margate’s tourist office. But someone did. You only have to walk down the half-shuttered high street, or stroll along the seafront past the tattered arcades, to feel like the place has been generally neglected, dejected, overlooked. Even on a sunny day, there’s something melancholy in the salt air, and it doesn’t feel like there are many sunny days in Margate anymore. The story of the British seaside is a story of decline, and it’s a story that is etched in the sands and worn into the seawalls here; but Emin isn’t the only one that’s been trying to overwrite it.

There’s the Turner Contemporary, a small but perfectly formed art gallery hunched overlooking the grey steel Channel. Then there are the very good coffee shops and yoga studios, restaurants and galleries that have sprung up in the Old Town, like the Turner put down roots which began to sprout and flower throughout the neighbouring streets. There are shops that sell nothing except succulents and expensive notebooks and replica Eames loungers. There’s a shell grotto, a hard-to-explain curio that might be an ancient pagan temple or a bored Victorian’s idea of a joke. There are lots and lots of pubs. Maybe it’s just because Brighton got too expensive, but things are happening in Margate. They don’t call it Shoreditch-on-Sea for nothing.

Of course, I’m attuned to enjoy this kind of thing. I’m DFL - Down From London, on the fast train from St Pancras - and it’s hard to escape the feeling that all these things have been designed for passing trade like me and not for those who have been settled on the Isle of Thanet for generations. But the seaside is a transient place that changes with the tides, and if once they came for windbreaks and sticks of rock, now they can come for abstract expressionism and single origin Ethiopian roasts.

One thing that locals and interlopers alike can agree on is the value of a good pint. This is Kent of course, a homeland for hops, and even if the bines and oasthouses don’t extend out into marshy hinterland here, their spirit does. Margate has become a hotbed of micropubs, those mono-roomed dens of real ale and real chat, and all the ones I passed were crammed to the rafters with a wide range of people quaffing away.

I’d hoped to sample a few micropubs, but a combination of two factors - bad weather, and a day-long trip to A&E after our jaunt to Dreamland funfair turned into a nightmare when my daughter slipped and cut her head (no lasting damage, thankfully) - meant we only really had time to drink in one place.

Night Swift used to the Margate outpost of The Bottle Shop, the bar, off licence and beer distributor which collapsed in March. I’d been a regular at the Bermondsey branch, which is apparently on its way to becoming a new Beer Hawk (ABI) venue, but in Margate, a team of former staff have taken it over and kept the same premises, same atmosphere, and most importantly, the same love of great beer, and turned it into a new independent venue.

It was perfect. Whether hiding from a gale howling off the sea, or tending to a bandaged and sorry-for-herself toddler, Night Swift was the perfect place to sit and sip. Hazy ales from Pressure Drop, saisons from Burnt Mill, and 10 Apple Stout, a 12% imperial stout aged in calvados barrels from Pohjala and To Ol - it was a haven, a paradise, the bar at the end of the world.

So take the train, venture down the estuary and see the true eastern edges of this country, this isle at the fringe of our island. There are arcades and art galleries, bingo halls and boutiques, postcards and pubs. One pub in particular.

Oh, I do like to be beside the seaside.

The It Crowd

“I used to be with it,” Abe Simpson once pronounced, “but then they changed what it was. Now, what I’m with isn’t it, and what’s it seems weird and scary to me. And it will happen to you, too.”

I’ve been thinking about “it” a lot recently. It’s only natural that The Simpsons, the foundational text of my youth, would possess somewhere within its multitudes this perfect expression of losing “it”. The older I get, the less with it I increasingly become, and the more questions I begin to ask of it. “Is this it?” The Strokes once asked through the filtered ennui of their debut album. Is this it, I now ask myself. Is this it? Is this?

One group of people who know what it is are the swollen and sunburnt residents of ITV2’s Love Island. Like most of the rest of the nation, I’ve become addicted to their escapades - Curtis’ drama school theatrics and creepy youth pastor energy, Tommy Fury’s leonine proclamations, Lucie’s desperate attempts to make the expression “bev” catch on. It is central to these people. It has literally become their catchphrase this season: “It is what it is”. It Is What It Is has become everything to them, from a heartfelt bleat of resignation to a triumphant declaration of objective truth. It is simple to the point of banality yet it would take a philosopher volumes to unpack - the all-conquering expression. It Is What It Is.

On one level, of course it is what it is. It could hardly be anything other. X is what x is, y is what y is. What’s done is done, what will be will be, what it is, it is. For good or for ill, the thing is always itself. Best to just accept it. Missed the bus? It is what it is. Missed a penalty? It is what it is.

But there’s also something affirmative and positive about it. When other things have misled or deceived, when something has turned out not to be what you thought, don’t despair - it is what it is. It has permanence. It has consistency. It will never let you down.

And then we come back to Abe and his sage old words. “Then they changed what it was”.

What Carlsberg was, was a known quantity. It was reliably one of the cheapest lagers available. It was domestic strength but with continental branding. It was nice green cans and snappy slogans you could quote in conversations. It was rarely anyone’s first choice. It did the job.

But they changed what it was, from “head to hop”. They admitted, shock horror, it probably wasn’t the best beer in the world. They committed to changing its recipe, rebranding it as a “Danish Pilsner”, focusing on quality and not just price. It it what it is. But apparently it is not what it was.

Trying to describe the flavour of new Carlsberg feels a bit like trying to interpret the phrase “it is what it is” - a circular exercise, infinitely self-referential, with no beginning and no end. Have you had a mass-produced lager before? It tastes like that. It’s inoffensive, broadly subtle, not sweet enough to count as cereal or biscuit, not bitter enough to bring to mind herbs or astringent grassiness. It doesn’t contain fruit or funk. It’s just dry enough to encourage the next gulp. It is pleasant enough in an absent-minded way, without pushing me to say it’s good, exactly. Is it better than it was?

As noted philosopher Thomas Furious would say, with a shrug and a smile: it is what it is.

Spain Relief

One of my favourite pastimes - and I’m aware this might sound strange - is walking around foreign supermarkets. If pushed between visiting a local attraction - a castle, say, or a particularly well preserved Franciscan priory - and a large branch of Carrefour or Pingo Doce, then I’ll choose the second option every time. There’s something fascinating in the uncanny differences between supermarkets abroad and supermarkets at home. Walkers becomes Lays. Dairy Milk becomes Milka. Everything seems broadly familiar and yet profoundly different at the same time, a small vision into the life you would have lead if you’d only been born in Toledo or Nantes instead of Hull or Cirencester.

Nowhere are these differences more profound than in the beer aisle. Take Spain, for example, where I’ve just been. Instead of a the UK’s stacks of crates all trying to offer the lure of foreign exoticism - Belgian, Danish, French, Italian, Australian and all the rest, even if they all come from the same high-volume plants in the East Midlands - nearly everything in the Spanish supermarket traded on locality. Cruzcampo, Alhambra, Aurum - all of the big brands were from relatively close by. Add in the fact that you’re welcome to break up multipacks to buy as many as you like, and that they’re all diddy 330ml cans - well, it’s all too much to resist. So I brought them all.

I was thinking that I could provide accurate tasting notes of all them, but to be honest, there really wasn’t much to tell them apart. They were easy-drinking, low flavour, thirst-quenching adjunct lagers. At a push I maybe preferred Cruzcampo, but that might just be the Falstaffian figure on the can endearing me to it. But it doesn’t matter. At the low low rate of 22c a can (in the case of the charmingly retro Cordon Gard) it’s very hard to go wrong.

That’s not to say there isn’t excellent beer in Malaga. Like many cities, it’s got its share of “craft” offerings as well. We were in the area for a wedding, but spent two child-free nights in the city itself, taking in the tapas and some of the non-supermarket sights. It’s a lovely place. We strolled the Alcazaba, the palatial fortress dating from the era of Islamic rule in the city, where you sit by the tinkling fountains and overlook the harbour and the Mediterranean, almost imagining you can see Africa. We toured the Cathedral, a multifaceted jewel of the Spanish renaissance, where gargoyles shaped like cannon take aim at monstrous baroque altarpieces. We walked around the Bishop’s Palace, the only souls there aside from a team of bored security staff, admiring the painted wooden sculptures, a disconcerting bridge between classical marbles and Warhammer figurines. The city is small and mainly beautiful. Your shoes squeak on the shiny, polished stones.

There are a couple of well-thought of beer bars. Ceverceria Arte & Sana was the first we tried, which had a list featuring a couple of Spanish beers alongside Lervig, Pilsner Urquell and others. It was quiet in the early evening - the Spanish really do prefer to go out late - but I had a hazy, lactose-dosed NEIPA from Spanish brewery MALANDAR, and while it was a bit overly cloying, it made a nice change from endless lagers. Around the corner is Central Beers, a more open space with timber accents than brings to mind Barcelona’s legendary BierCaB, though the list doesn’t quite live up to it. It’s nothing to sniff at though, and I enjoyed a Basqueland Brewing What the F*** is DDH?, juicy and well balanced beer that went down well in the warm evening heat.

We also stopped in quickly at La Fabrica, a brewpub set up as the experimental arm of the aforementioned Cruzcampo (which is owned, ultimately, by Heineken). It’s an impressive space - almost eerily reminiscent of BrewDog’s enormous Tower Hill outpost, right down to the bleacher-style seating in one corner. Sadly the beer wasn’t worth sticking around for. I tried the inhouse pale ale, and, blindfolded, would’ve guessed it was Schweppes lemonade.

The single best beer I had was in El Pimpi, a Malaga institution, a rambling multi-roomed bodega full of nooks and crannies and an embarrassment of pictures of minor Spanish celebrities signing barrels (plus local hero Antonio Banderas). There, sat at one of the many bars, beneath a taxidermied bull’s head and an enormous painting of a rained-out corrida, I had a caña (and I am a complete convert to caña drinking - no more of this pint nonsense, give me either fleeting glasses of icy beer that disappear with a breath, or else a Maß I can get lost in) of Victoria Malaga, and it was just perfect - a slight malt sweetness, and a herbal hop finish, that combined with the setting and seating, I was ready to up sticks and settle down in the Costa del Sol forever.

All I need is a bar like that, and a really good supermarket.

Great Scots

Everyone in Edinburgh looks like a solicitor.

Something about the serious grey-black stone of the buildings, the weight of the masonry or the angle of the streets - whatever it is, it seems to cast everyone in a suit and tie, smart glasses, a briefcase stuffed with case files and legal briefs.

It can’t be true, of course. Edinburgh is a bustling city, full of bus drivers, footballers, street sweepers and accountants - some solicitors, sure, but not nothing but solicitors. The solicitor thing is a mirage, a sense impression, a residual feeling that arises from the seriousness of the city - a city of statues and statutes, museums and monuments, colleges and kirkyards. There’s an elegance to Edinburgh, a certain refinement. Maybe that’s only shown off to tourists like me - Trainspotting would suggest that it’s not all Georgian architecture and Harry Potter tours - but there seems to a be a dignified streak that runs through the capital, as wide as the Royal Mile.

The Stockbridge Tavern

There are still pubs though. Some might have distilled the elegance of the city they inhabit, but lots are just pubs, a place beyond elegance, where what matters is proper patter - and beer of course. I had a couple of days in the city to try and explore some of city’s beer. For most of it I was accompanied by an energetic toddler, which did prove to be something of a spoiler. The first few places I tried to visit - on a sunspolied, taps aff Friday afternoon - didn’t allow children (I’m not writing this to complain - I understand why pubs may want to be child-free) so I had to skip a few spots through my compiled list of best places to drink in town. Thankfully, a place at the top of many lists - The Hanging Bat - was happy to let me stow a pushchair in the corner, and I was glad they did. A few choice lines of local cask ales and a DEYA tap takeover of the keg lines meant this was a fine place to spend some time. It’s cosier than your average modern beer bar, with deep red sofas and lots of wood - a nod to the city’s elegance, but filled with edgier delights.

Trekking back to the hotel, arcing around the city’s central cliffside, thrusting its castle aloft like Simba atop Pride Rock, I impulsively stopped at the Innis & Gunn taproom I passed. It’s been years since I drank their “barrel-aged” ale, though there was a time, pre-craft revolution, when I loved it. At the bar, I got drawn in by the tank-fresh lager, but I should have gone old school - the lager was bland, fizzy, freezing cold. I saw four-packs alongside Tennent’s in every supermarket, and I’d choose the Tennent’s every time (and indeed, I did). Still, they had high chairs, which I appreciated.

Fierce Beer Bar

A bit later, I was able to sample some places sans toddler, which gave me a slightly deeper appreciation for Edinburgh’s pubs. I got the range too, starting in the Stockbridge Tavern, a sunlit corner pub filled with a Friday night post-work crowd, a real mix of ages and genders and beverages crowded around well scrubbed tables and a bustling bar. I’d planned to drink local, but when I saw North’s Transmission on cask, a 6.9% west coast IPA, I couldn’t resist, and I didn’t regret my lack of impulse control. It was a proper “wow” pint, with huge citrus rolled around a subtle cask haze. I almost had a second, when I spotted a Cross Borders Heavy on keg, and knew I had to oblige - it was everything I expect a heavy to be, bristling with toffee apple brittleness.

I finished the evening with a quick visit to the newly opened Fierce Beer Bar in the New Town. A third of Barrel Aged Very Big Moose - 12.5% and wearing it well - was a lovely way to round out an evening, still warm and light enough to sit out past 9pm.

And so to Glasgow. It wasn’t until the train slunk through the city’s grey and rainy edgelands and the carriages began to fill up with men in green and white shirts that I realised it was a match day (Celtic and Hearts - plus a rugby game to boot), but luckily I hadn’t been planning to hit the pubs - or sit atop a traffic light getting cans lowered down to me. As it turned out, we couldn’t have gone out if we wanted - when we tried to walk into Shilling Brewing Co, we were met with another “no kids allowed” (as an aside - is Scotland particularly adverse to letting kids in drinking establishments, or is London the outlier in letting them in?)

The Wellpark Brewery from the Necropolis

For the first evening I sampled some supermarket staples instead, with a couple of Williams Bros beers. Joker, their IPA, was bland and unfocused - perhaps it had lost a little something on a warm shelf, perhaps it never had it. Caesar Augustus, their IPL, was a more intriguing affair, with a brash, grassy nose, and a pleasing floral flavour.

The next day, after wandering the coal-smoke scented galleries of the Kelvingrove museum, I popped into Grunting Growler (again, no kids allowed, except to watch me choose something from the fridge - Tempest Mexicake, a vat of red chilli flakes, powdery chocolate and moist sponge - to take away). In the end, it was BrewDog which was happy to host the whole family, and a pint of Zombie Cake, with it’s neat nutty nose, was a nice way to break the duck.

Scotland’s favourite beer

On the last day, we walked out to St Mungo’s Cathedral and the Necropolis, that glowering townscape of tombs that overpeers the beloved Wellpark Brewery, the source of every golden drop of Tennent’s. It was hard to imagine, on a rainswept day, watching the facility contribute its own clouds to the crowded sky, that the Necropolis didn’t have some strange relationship with the brewery; that the rain water didn’t flow down through the burial mounds and terraces, through the dark, stony earth, and into the deep, unseen spring that gave Wellpark its name, and impart something particular into the water - not just the minerals and nutrients and pH level, but a distinct spirit and character - the very atoms of William Motherwell and Archibald Douglas Monteath, Walter Macfarlane and Andrew McCall, all the authors and lawyers and engineers and explorers that made Glasgow and Scotland the engine of an Empire. They don’t put this stuff on the Tennent’s marketing copy, but maybe they should.

Nightmare of Cake

Escaping down the hill we took shelter in the Drygate Brewery, an offspring of Tennent’s and Williams Bros, focussed on modern beers alongside a good menu and comfortable taproom slash restaurant. It was an impressive set-up, and the beers stood up well for the most part. Crossing the Rubicon, an IPA, was an overly sweet candied mess, but the Seven Peaks session IPA was much better, dry, and with a peach-driven Mosaic character. But the real standout was my third “cake” beer of the weekend, Nightmare of Cake, a gloopy, unctuous mess of a beer, overstuffed with marshmallow and raspberry and milk chocolate and all things nice - “Made from chemicals by sick bastards” as the menu had it, and every ridiculous element from each corner of the periodic table only made it better.

Perhaps it had some dead Scottish solicitors in it too. The quest for pastry stout novelty continues.

What Fresh Hell

This is a tale of two beers. One American, one British; one bottled, one canned; one passable, one fantastic; most importantly perhaps, one old, one new.

At heart though, there is more that unites these beers than divides them. Both are hop-forward IPAs, and both have built a reputation as modern classics. They’re both beers I’d be happy to choose when faced with an overwhelming taplist, or a crowded supermarket shelf. One is Bell’s Two Hearted Ale, and the other is Thornbridge’s Jaipur.

It was in January when I had my run-in with Two Hearted. It wasn’t my first - in fact, if pushed, Two Hearted would be one of my desert island beers. All Centennial, all action, it can be a sublime beer, a thunderous march of grapefruit and pine that blows away the cobwebs and clears the sinuses. That’s why, when I saw it on the shelf of a South Florida Target, I jumped at the chance to pick up a six pack of my old favourite. I did a cursory check of the date - barely a week old! - threw it in the trolley alongside a case of High Life and looked forward to the next few evenings.

But when I got it home and slumped down in front a hockey game, the familiar roaring notes of acidic citrus seemed dull and muted, like trying to listen to a pop song with your hands over your ears. It wasn’t bad, exactly, there was a syrupy sweet note followed by a rustic, earthy bitterness, but the edges were soft and rounded, its corners padded with woolen blankets and bubble-wrap.

I looked at the label again, and suddenly it made sense. It had been bottled in January, but the problem was, it was the previous January. What I thought was a week old, was a year and week old - I’d been caught out in the same way I used to write the wrong date on all my school work after the sprawl of Christmas. No wonder the beer was all wrong, I thought. No wonder it just seemed off.

Flash forward to this weekend. The Eurovision Song Contest. One of my favourite nights of the year, when I meet up with a bunch of old friends and settle in for a night of drinking and key changes and bondage gear (the Icelandic entry, not me and my friends). I grabbed some beers from the Tesco at the bottom of my friend’s block of flats to take up, and picked up two four-packs of Jaipur in that kind of “well I can’t take a case of Fosters, but I also don’t want to drop £50 in a bottle shop” kind of way that seems to crop up increasingly often.

Cracking it open ready to enjoy a simple glugging beer, I was stopped in my tracks, even before I took a swig - the aroma leapt out of the tin, a tuft of fruit salad chewiness, and the taste was perfect, part Nordic Fir and part marmalade shred, decidedly bitter but without being harsh or drying. It was sublime, a platonically good beer, and a perfect revelation when I’d expected merely fine. I checked the can - and discovered it was three days old.

I’ve never been a freshness truther before, in the same way I’ve generally been agnostic about cold chains and indifferent to food pairings. I’ve got no problem with other people being excited about it or preaching the good news, but if you hand me a pamphlet on it, it’s probably going to find its way into the bin before long. It’s not like I didn’t believe that fresh beer - especially hoppy, fresh beer - was better, it’s just that I’d never really had it so starkly demonstrated before. It was like a veil had been lifted. Suddenly, I was a true believer.

I don’t know if Tesco’s stocking process will mean beer this fresh is a regular on shop shelves, or whether this was one lucky find amid a sea of “shelf turds”. But it won’t hurt me to keep checking. When there are two beers on offer, I know for sure which one I want.

Anthem for Doomed Youth

Note to readers: Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita is presented as the memoir-cum-confessions of a maniac hiding behind the ominous pseudonym of Humbert Humbert. The other players and settings in the story have, we are told in a foreword by the briskly useful John Jay Jr, been masked with false names and re-ordered places, to protect those innocent parties “that taste would conceal and compassion spare”. The only true name in the book is its titular figure, Dolores, Dolly, Lo, Lolita; “her first name is too closely interwound with the inmost fibre of the book to allow one to alter it”.

As it is with poor unfortunate Dolores Haze, so it is with the pub that forms the topic of this piece. While I too would like to protect those who need it, the name of the pub is too central to what it is to keep it out, and in any case, as William Burroughs put it - perhaps there are no innocent bystanders. What I do need to say, though, is that this all happened more than a decade ago, in a small town far away, and if anything was ever less than legal, it was my fault and mine alone, and no single venue, landlord, management company or anyone else should be held responsible. What’s more, I’m sure that nowadays, this pub is an upstanding institution of great moral character, that has long ago shed any of the seedy connotations it carried back in the heady days of the post-Millennium. I wouldn’t know. I’m not going back.

***

Because I was a particularly nerdy 16-year-old, I asked my father’s permission to go out drinking for the first time. And, because I was a particularly nerdy 16-year-old, and there was in his view very little trouble that I could wind up getting into, he said yes. So, one Friday night, dressed in my finest shirt and shiniest shoes, we headed down town to a pub where my mate Will guaranteed we could get served.

We couldn’t. As it turned out, they’d been raided the week before by the police, who’d checked the IDs of all the furtive drinkers huddled in the back room, and given the owners a very stern talking to. As soon as we’d opened the door, a very large man with a very bald head asked to see our papers, and even though we insisted that we were just there to meet a friend, who was already sat inside, conspicuously avoiding our nods and waves, the door was closed to us, the merry lights glowing behind the bullseye panes of glass like the light Gatsby yearns for at the end of Daisy’s dock. It was slightly humiliating, but also, in some ways, a relief - what exactly were we going to do once we got inside? What were we meant to order? A whole pint of it? But something about the experience was scarring enough that we never tried to go back there again. I don’t even remember the pub’s name now, but it wasn’t long until it turned into restaurant serving British classics. It has mediocre reviews.

After this early setback, our drinking plans were scaled down. We knew we could have pints of gassy Cobra in the local balti house, but after one awkward evening where it was made clear we had to order main courses, not just keema naans, before we could have the beer, it was an expensive proposition for a boy on a dishwasher’s salary. If we wanted to drink in a pub, there was only one other option - the Doom.

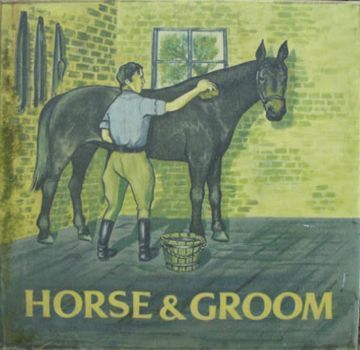

The Horse & Groom, known locally as the Doom & Gloom, or just the Doom for those in the know, was that pub - the one in town with a reputation for serving any school kids who had the foresight to take off their tie and blazer. It should have been our first port of call, but something about its reputation - a slight edge, an air of danger - meant we wanted to build up some experience in advance of wading in.

After nearly bankrupting ourselves on lamb saags, a decision was made: we would invest in fake IDs, purchased from a website of questionable repute, and present ourselves down at the Doom in the time-honoured fashion - sneaking into the “beer garden” (a concrete yard with two picnic tables overlooking the bus station), making our way into the pool room, then finally, nervously, desperately, heading up to the bar.

The plan had teething problems. In the first instance, my fake ID arrived with the wrong date on it - it actually made me seem younger than I actually was, which was very much against the point. Surprisingly for a website which peddled questionably legal products, the customer service was outstanding, and a couple of emails later saw a replacement winging its way to me in no time at all. I remember it was pink, vaguely like a driving license, but with some dodgy holograms that said something like “European Identity”, which didn’t quite have the racist connotations it does now. No bouncer with more than a primary-level education would have been fooled by it for a second, but it was the thought that counted - if only we looked like we were meant to be there, we thought, we’d be accepted.

And so, one fateful night, we headed down town again. We might have bought chips first, or maybe hit up the Chinese (noodles were a whole meal in themselves - far more reasonable that the balti house). But at some point, under cover of darkness, with the smell of cigarette smoke wafting across the car park, we approached the Doom.

Furtively, we opened the gate and slipped into the yard. A crowd of students from the year above - some of whom may have even been of legal drinking age - were knocking back pints and smoking with a vigour only teenagers possess. They didn’t seem to notice us. We had passed the first test.

Next, into the pool room. We opened the door and stepped into the pub’s back room, where a dented and defeated pool table, slightly too large for the space that held it, was the focal point for another group of people familiar from school. We made out like we belonged. Lots of nods. Lots of “alright?”s. Chuckling nervously as we ducked under pool cues as they banged off the wall as every shot was lined up. Into the corridor between the pool room and the bar. A tactical decision - into the gents.

“How are they doing?” Shit. I hadn’t expected an interrogation at this early stage. In fact, I didn’t even know what I was being interrogated about. “Huh?” I said, uselessly. The man at the stainless steel trough nodded at my shirt. “Liverpool? How they doing?”

I wasn’t wearing a Liverpool shirt. Was this a test? What the fuck was he talking about? I tried to recover. He seemed slightly drunk, but not paralytic, friendly rather than aggressive. My top was a plain, red polo shirt, nothing to do with Liverpool, but I guess it was an easy mistake to make, if you ignored the fact lots of teams plays in red, we were nowhere near Liverpool, and I obviously wasn’t wearing a football shirt. “Not bad!” I said, despite not knowing a single thing about the recent performance of Liverpool FC. He nodded, seemingly satisfied, and refocussed on his urinating. I tried to do the same, which wasn’t easy, as I braced for further football chat. Thankfully, the man finished and shambled out. The next trial was over.

But the biggest challenge was still to come. The dreaded bar. The front room was a large space, with two raised areas either side of the front door, which made the bar seem sunken and low in comparison, a kind of illuminated trench, mobbed with people. It ran across a whole wall, with repetitive fonts offering the same few beers in the same pattern, and a similarly small selection of spirits on the wall behind. A concerningly large amount of real estate had been given over to some sort of Jagermeister machine, which I never saw in operation. For all I know it had never been used at all, perhaps had never been purchased with the intention of use - it had merely manifested itself one Friday evening, a malignant entity that grew out of a collection of congealed shot glasses and was now too cumbersome to remove.

I made my way up, fake ID clutched nervously in my sweaty palm. The crowd in front of me seemed to part in a way which would have been miraculous nowadays, but then felt like a kind of omen - all of a sudden, I was face on with a barman, not much older than I was, who was staring me down with a practiced eye that practically screamed “Nope” at me. I approached the bar. Nodded. He nodded back.

“Can I ge-”

“ID, please.”

Shit. That wasn’t good. Hadn’t even let me order my Fosters (it was that, I think, Guinness, or Worthington Creamflow - not an inspiring selection, but more than enough for me, even if I’m still not entirely sure what Creamflow is).

I handed it over, still clammy from my paw. He raised it to the light, turned it over, turned it back again. His lips moved slightly, as if he was sounding something out to himself. After a moment, he laid it on the sticky bar.

“That’s fake.” The words hung there for a second. The pub was loud, but in that moment, all I could feel was the deafening silence as I fell into the hollow of a skipped heart beat. He said something else, something I couldn’t hear over the deafening void.

“What did you want?”

“Fosters, please,” I croaked, and he began pouring. Shit. I’d done it. I’d been found out, and he didn’t even care. I had conquered the Doom, and I’d only had to shred my nerves and embarrass myself to do it. I had made it. I had achieved the sweetest victory of all. I was drinking underage.

That night was my initiation. I was part of the Doom now, and the Doom, for all its faults, was part of me. I learned to play pool on its table, where every shot had to be taken at an odd angle so you didn’t hit the wall. I developed a lifelong fondness for bottles of Newcastle Brown Ale, once I realised every tap in there poured something that tasted either like vinegar or batteries. I saw my first stripper, entertaining the world’s saddest stag party, who did something unmentionable with a bottle of Budweiser and made me very upset for some time to come. I watched my friend get in a fight with a man with a neck tattoo over a question of darts etiquette, that didn’t involve any thrown punches, but did feature lots of aggressive chest barging, like two novelty wind-up toys lined up against each other. I sat in there all day on my friend Rob’s birthday, while he drank endless pints of Guinness, and we couldn’t believe how much he was putting away, until he stood up to go to the loo, fell over, and didn’t get up again until the next morning. Then there was Nick’s birthday, where we all chipped in for a dirty pint, and the barman returned a glass of brown evil, that put Nick on the floor like a sack of wet cement. I worked my way through all of the bar’s dubious shots, with names like Slippery Nipple and Flatliner, which featured a layer of Tabasco between two things even worse. I was there on A-level results night, when Jonesy stood on a table and hit his head on the TV bracket above, knocking it clean off the wall, and it wasn’t clear how someone hadn’t been killed by the massive appliance collapsing on top of them. I was there through it all, good times and bad.

I don’t think I ever went back once I turned 18. When I was free to go to any pub, the one pub that had welcomed me before seemed less enticing, less sexy, less cool. Maybe also because it was a really shit pub. But for a time, it was my pub.

My refuge.

My Doom.