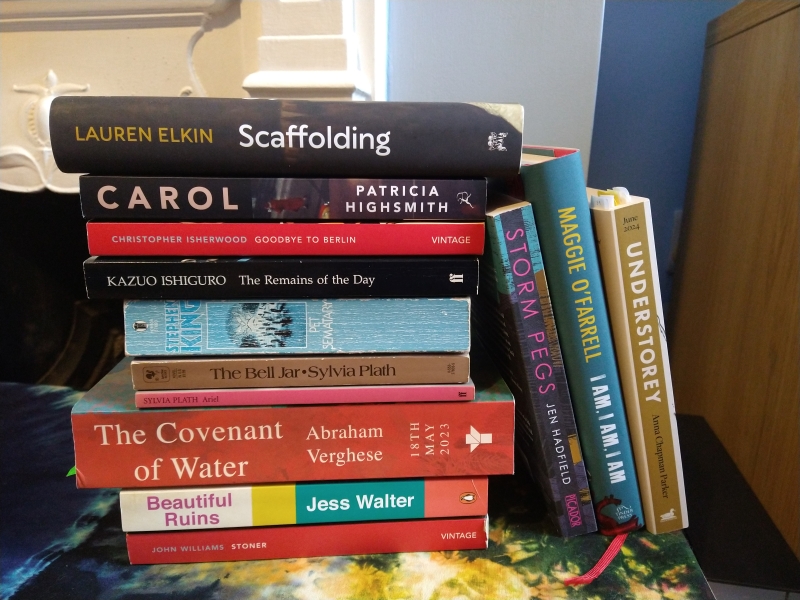

Best Backlist Reads of the Year

I consistently find that many of my most memorable reads are older rather than current-year releases. Four of these are from 2023–4; the other nine are from 2012 or earlier, with the oldest from 1939. My selections are alphabetical within genre but in no particular rank order. Repeated themes included health, ageing, death, fascism, regret and a search for home and purpose. Reading more from these authors would probably help to ensure a great reading year in 2026!

Some trivia:

- 4 were read for 20 Books of Summer (Hadfield, King, Verghese and Walter)

- 3 were rereads for book club (Ishiguro, O’Farrell and Williams) – just like last year!

- 1 was part of my McKitterick Prize judge reading (Elkin)

- 1 was read for 1952 Club (Highsmith)

- 1 was a review catch-up book (Parker)

- 1 was a book I’d been ‘reading’ since 2021 (The Bell Jar)

- The title of one (O’Farrell) was taken from another (The Bell Jar)

Fiction & Poetry

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin: Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in this intellectual tour de force. As history repeats itself during one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. This was our collective runner-up for the 2025 McKitterick Prize, but would have been my overall winner.

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin: Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in this intellectual tour de force. As history repeats itself during one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. This was our collective runner-up for the 2025 McKitterick Prize, but would have been my overall winner.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith: Widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer, meets a wealthy housewife – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – in a New York City department store one Christmas. When the women set off on a road trip, they’re trailed by a private detective looking for evidence against Carol in a custody battle. It’s a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds and shares the psychological intensity of Highsmith’s mysteries.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith: Widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer, meets a wealthy housewife – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – in a New York City department store one Christmas. When the women set off on a road trip, they’re trailed by a private detective looking for evidence against Carol in a custody battle. It’s a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds and shares the psychological intensity of Highsmith’s mysteries.

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood: Isherwood intended for these autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin.” Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 reveal a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. Famously, the longest story introduces club singer Sally Bowles. I later read Mr Norris Changes Trains as well. Witty and humane, restrained but vigilant.

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood: Isherwood intended for these autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin.” Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 reveal a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. Famously, the longest story introduces club singer Sally Bowles. I later read Mr Norris Changes Trains as well. Witty and humane, restrained but vigilant.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro: I first read this pre-blog, back when I dutifully read Booker winners whether or not I expected to like them. I was too young then for its theme of regret over things done and left undone; I didn’t yet know that sometimes in life, it really is too late. When I reread it for February book club, it hit me hard. I wrote no review at the time (more fool me), but focused less on the political message than on the refined depiction of upper-crust English society and the brilliance of Stevens the unreliable, repressed narrator.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro: I first read this pre-blog, back when I dutifully read Booker winners whether or not I expected to like them. I was too young then for its theme of regret over things done and left undone; I didn’t yet know that sometimes in life, it really is too late. When I reread it for February book club, it hit me hard. I wrote no review at the time (more fool me), but focused less on the political message than on the refined depiction of upper-crust English society and the brilliance of Stevens the unreliable, repressed narrator.

Pet Sematary by Stephen King: A dread-laced novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Is bringing the dead back a cure for grief or a horrible mistake? A sleepy Maine town harbours many cautionary tales, and the Creeds have more than their fair share of sorrow. Louis is a likable protagonist whose vortex of obsession and mental health is gripping. In the last quarter, which I read on a long train ride, I couldn’t turn the pages any faster. Sterling entertainment, but also surprisingly poignant. (And not gruesome until right towards the end.)

Pet Sematary by Stephen King: A dread-laced novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Is bringing the dead back a cure for grief or a horrible mistake? A sleepy Maine town harbours many cautionary tales, and the Creeds have more than their fair share of sorrow. Louis is a likable protagonist whose vortex of obsession and mental health is gripping. In the last quarter, which I read on a long train ride, I couldn’t turn the pages any faster. Sterling entertainment, but also surprisingly poignant. (And not gruesome until right towards the end.)

The Bell Jar & Ariel by Sylvia Plath: Given my love of mental hospital accounts, it’s a wonder I’d not read this classic work of women’s autofiction before. Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. An enduringly relevant and absorbing read. / Ariel takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp and the first and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable.

The Bell Jar & Ariel by Sylvia Plath: Given my love of mental hospital accounts, it’s a wonder I’d not read this classic work of women’s autofiction before. Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. An enduringly relevant and absorbing read. / Ariel takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp and the first and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese: Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but this saga sticks with one Kerala family in every generation of which someone drowns. I enjoyed the window onto St. Thomas Christianity, felt fond of all the characters, and appreciated how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intelligent soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese: Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but this saga sticks with one Kerala family in every generation of which someone drowns. I enjoyed the window onto St. Thomas Christianity, felt fond of all the characters, and appreciated how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intelligent soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary.

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: I was captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime opus, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in the summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. Warm, timeless and with great scenes, one of which had me in stitches. Fantastic.

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: I was captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime opus, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in the summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. Warm, timeless and with great scenes, one of which had me in stitches. Fantastic.

Stoner by John Williams: What a quiet masterpiece. A whole life, birth to death, with all its sadness and failure and tragedy; but also joy and resistance and dignity. One doesn’t have to do amazing things that earn the world’s accolades to find vocation and meaning. Just as powerful a second time (I first read it in 2013). I was especially struck by the power plays in Stoner’s marriage and university department, and how well Williams dissects them. It’s more about atmosphere than plot – and that melancholy tone will stay with you.

Stoner by John Williams: What a quiet masterpiece. A whole life, birth to death, with all its sadness and failure and tragedy; but also joy and resistance and dignity. One doesn’t have to do amazing things that earn the world’s accolades to find vocation and meaning. Just as powerful a second time (I first read it in 2013). I was especially struck by the power plays in Stoner’s marriage and university department, and how well Williams dissects them. It’s more about atmosphere than plot – and that melancholy tone will stay with you.

Nonfiction

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield: Not a straightforward memoir but a set of atmospheric vignettes. Hadfield, a British Canadian poet, moved to Shetland in 2006 and soon found her niche. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms the long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic comes the unexpected joy of a partner and pregnancy in her mid-forties. I savoured this for its language and sense of place; it made me hanker to return to Shetland.

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield: Not a straightforward memoir but a set of atmospheric vignettes. Hadfield, a British Canadian poet, moved to Shetland in 2006 and soon found her niche. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms the long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic comes the unexpected joy of a partner and pregnancy in her mid-forties. I savoured this for its language and sense of place; it made me hanker to return to Shetland.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: (The final book club reread.) The memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for boring intermediate material. These pieces form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. The last two essays are the pinnacle.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: (The final book club reread.) The memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for boring intermediate material. These pieces form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. The last two essays are the pinnacle.

Understorey: A Year among Weeds by Anna Chapman Parker: I owe this a full review in the new year. Parker set out to study and sketch weeds as a way of cultivating attention and stillness as well as celebrating the everyday and overlooked. Daily drawings and entries bear witness to seasons changing but also to the minute alterations she observes in herself and her children. For me, this was all the more special because I’ve holidayed in Berwick-on-Tweed and could picture a lot of the ‘overgrown’ spaces she honours by making them her subjects.

Understorey: A Year among Weeds by Anna Chapman Parker: I owe this a full review in the new year. Parker set out to study and sketch weeds as a way of cultivating attention and stillness as well as celebrating the everyday and overlooked. Daily drawings and entries bear witness to seasons changing but also to the minute alterations she observes in herself and her children. For me, this was all the more special because I’ve holidayed in Berwick-on-Tweed and could picture a lot of the ‘overgrown’ spaces she honours by making them her subjects.

What were some of your best backlist reads this year?

Some 2025 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese (724 pages)

Shortest book read this year: Sky Tongued Back with Light by Sébastien Luc Butler (a 38-page poetry chapbook coming out in 2026)

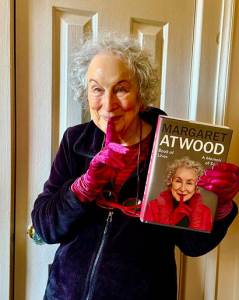

Authors I read the most by this year: Paul Auster and Emma Donoghue (3) [followed by Margaret Atwood, Chloe Caldwell, Michael Cunningham, Mairi Hedderwick, Christopher Isherwood, Rebecca Kauffman, Stephen King, Elaine Kraf, Maggie O’Farrell, Sylvia Plath and Jess Walter (2 each)]

Publishers I read the most from: (Besides the ubiquitous Penguin Random House and its myriad imprints) Faber (14), Canongate (12), Bloomsbury (11), Fourth Estate (7); Carcanet, Picador/Pan Macmillan and Virago (6)

My top author ‘discoveries’ of the year (I’m very late to the party on some of these!): poet Amy Gerstler, Christopher Isherwood, Stephen King, Elaine Kraf, Sylvia Plath, Chloe Savage’s children’s picture books (women + NB characters, science, adventure, dogs), Robin Stevens’s middle-grade mysteries, Jess Walter

Proudest book-related achievement: Clearing 90–100 books from my shelves as part of our hallway redecoration. Some I resold, some I gave to friends, some I put in the Little Free Library, and some I donated to charity shops.

Most pinching-myself bookish moment: Miriam Toews’ U.S. publicist e-mailing me about my Shelf Awareness review of A Truce That Is Not Peace to say, “saw your amazing review! Thank you so much for it – Miriam loved it!”

Books that made me laugh: LOTS, including Spent by Alison Bechdel (which I read twice), The Wedding People by Alison Espach, Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito, Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler, The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, The Sacred Diary of Adrian Plass Aged 37 ¾, and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth

A book that made me cry: Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry

Best book club selections: Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam; The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro, I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell and Stoner by John Williams (these three were all rereads)

Best first line encountered this year:

- From Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones: “Hard, ugly, summer-vacation-spoiling rain fell for three straight months in 1979.”

Best last lines encountered this year:

- Is a River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane: “Death and love and life, all mingled in the flow.”

(Two quite similar rhetorical questions:)

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam: “If they didn’t know how it would end—with night, with more terrible noise from the top of Olympus, with bombs, with disease, with blood, with happiness, with deer or something else watching them from the darkened woods—well, wasn’t that true of every day?”

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam: “If they didn’t know how it would end—with night, with more terrible noise from the top of Olympus, with bombs, with disease, with blood, with happiness, with deer or something else watching them from the darkened woods—well, wasn’t that true of every day?”

&

- Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: “And even if they don’t find what they’re looking for, isn’t it enough to be out walking together in the sunlight?”

- Wreck by Catherine Newman: “You are still breathing.”

The Irish Goodbye by Beth Ann Fennelly: “Dear viewer of my naked body, Enjoy the bunions.”

The Irish Goodbye by Beth Ann Fennelly: “Dear viewer of my naked body, Enjoy the bunions.”

- A Certain Smile by Françoise Sagan: “It was a simple story; there was nothing to make a fuss about.”

- Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood: “We scribes and scribblers are time travellers: via the magic page we throw our voices, not only from here to elsewhere, but also from now to a possible future. I’ll see you there.”

Book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: The Harvest Gypsies by John Steinbeck (see Kris Drever’s song of the same name). Also, one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin mentioned lyrics from “Wild World” by Cat Stevens (“Oh, baby, baby, it’s a wild world. And I’ll always remember you like a child, girl”).

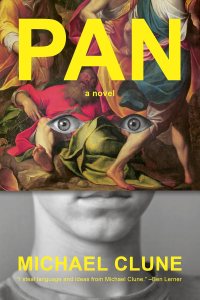

Shortest book titles encountered: Pan (Michael Clune), followed by Gold (Elaine Feinstein) & Girl (Ruth Padel); followed by an 8-way tie! Spent (Alison Bechdel), Billy (Albert French), Carol (Patricia Highsmith), Pluck (Adam Hughes), Sleep (Honor Jones), Wreck (Catherine Newman), Ariel (Sylvia Plath) & Flesh (David Szalay)

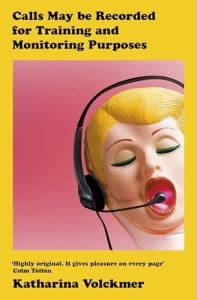

Best 2025 book titles: Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis [retitled, probably sensibly, Always Carry Salt for its U.S. release], A Truce That Is Not Peace by Miriam Toews [named after a line from a Christian Wiman poem – top taste there] & Calls May Be Recorded for Training and Monitoring Purposes by Katharina Volckmer.

Best book titles from other years: Dreams of Dead Women’s Handbags by Shena Mackay

Biggest disappointments: Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – so not worth waiting 12 years for – and Heart the Lover by Lily King, which kind of retrospectively ruined her brilliant Writers & Lovers for me.

The 2025 books that it seemed like everyone was reading but I decided not to: Helm by Sarah Hall, The Persians by Sanam Mahloudji, What We Can Know by Ian McEwan (I’m 0 for 2 on his 2020s releases)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Both by Elaine Kraf: I Am Clarence (link to my Shelf Awareness review) and Find Him! are confusing, disturbing, experimental in language and form, but also ahead of their time in terms of their feminist content and insight into compromised mental states. The former is more accessible and less claustrophobic.

Reporting Back on My Most Anticipated Reads of 2025

Most years I’ve combined this topic with a rundown of my DNFs for the year; this time I can’t be bothered to list them. There have probably not been as many as usual; generally, I’ve given a sentence or two about each DNF in a Love Your Library post. In any case, I hereby give you blanket permission to drop that book you’ve been struggling with. I absolve you of all potential guilt. It makes no difference if it has been nominated for or won a major prize, or if everyone else seems to love it. If for any reason a book isn’t connecting with you, move onto something else; you can always come back to try it another time, or not. Life is short.

So, on to those Most Anticipated books. In January, I picked the 25 new releases I was most looking forward to in the first half of the year, and followed it up in July with another 15 for the second half. Here’s how I fared with them:

Read and enjoyed: 14 (some will appear on my Best-of list!)

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood- Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel

- Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito

- Heartwood by Amity Gaige

- Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson

- Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman

- The Silver Book by Olivia Laing

- Ripeness by Sarah Moss

- Joyride by Susan Orlean

- Are You Happy?: Stories by Lori Ostlund

- Ghosts of the Farm: Two Women’s Journeys Through Time, Land and Community by Nicola Chester

- The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue: A Story of Climate and Hope on One American Street by Mike Tidwell

- Three Days in June by Anne Tyler

- Palaver by Bryan Washington

Read and found disappointing (i.e., 3 stars or below): 6

Read and found disappointing (i.e., 3 stars or below): 6

- Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

- Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein

- Mother Animal by Helen Jukes

- Heart the Lover by Lily King

- The Accidentals: Stories by Guadalupe Nettel

- Wreck by Catherine Newman

Skimmed (because it was disappointing): 1

- Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez

Currently reading / have read part of: 4

Currently reading / have read part of: 4

- Ghosts of the Farm: Two Women’s Journeys Through Time, Land and Community by Nicola Chester

- Jesusland: Stories from the Upside[-]Down World of Christian Pop Culture by Joelle Kidd

- The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley

- Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor

DNF: 1

- Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr.

Owned in print but haven’t read yet (one was received for my birthday and two just now for Christmas!): 3

Owned in print but haven’t read yet (one was received for my birthday and two just now for Christmas!): 3

- Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin

- Bread and Milk by Karolina Ramqvist

- The Antidote by Karen Russell

On my e-reader but haven’t gotten to yet: 9

- The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica

- Kate & Frida by Kim Fay

- Live Fast by Brigitte Giraud

- The Swell by Kat Gordon

- My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle by Rebe Huntman

- A Long Game: Notes on Writing Fiction by Elizabeth McCracken

- Tigers Between Empires: The Improbable Return of Great Cats to the Forests of Russia and China by Jonathan C. Slaght

Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts

Elegy, Southwest by Madeleine Watts- Alive: An Alternative Anatomy by Gabriel Weston

Haven’t managed to get hold of: 2

- O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy

- The Forgotten Sense: The New Science of Smell by Jonas Olofsson [my library has a copy]

I can’t resist compiling this list each year. In the first week of January, I’ll be previewing my 20 Most Anticipated titles for the first half of 2026.

Do you choose Most Anticipated books each year? (Or do you prefer to be surprised?) And if you do, do they generally meet your expectations?

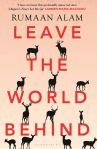

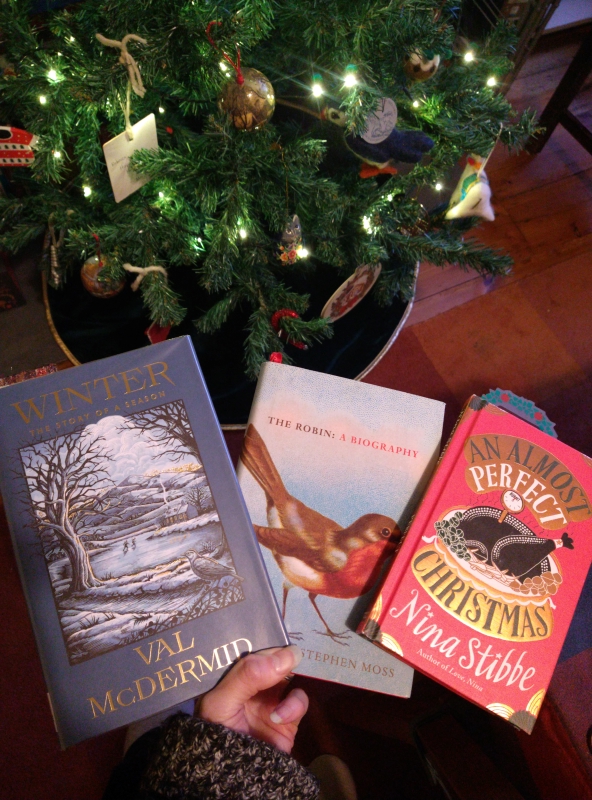

Seasons Readings: Winter, The Robin, & An Almost Perfect Christmas

I’m marking Christmas Eve with cosy reflections on the season, a biography of Britons’ favourite bird (and a bonus seasonal fairy tale), and a mixed bag of essays and stories about the obligations and annoyances of the holidays.

Winter by Val McDermid (2025)

I didn’t realize that Michael Morpurgo’s Spring was the launch of a series of short nonfiction books on the seasons. McDermid writes a book a year, always starting it in early January. She evokes the Scottish winter’s “Janus-faced” character: cosy but increasingly storm-tossed. In few-page essays, she looks for nature’s clues, delves into childhood memories, and traverses the season through traditional celebrations as she has experienced them in Edinburgh and Fife: Hallowe’en, Bonfire Night, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve. The festivities are a collective way of taking the mind off of the season’s hardships, she suggests. I was amused by her mother’s recipe for soup, which she described as more of a “rummage” for whatever vegetables you have in the fridge. It was my first time reading McDermid and, while I don’t know that I will ever pick up one of her crime novels, this was pleasant. I reckon I’d read Bernardine Evaristo on summer and Kate Mosse on autumn, too. (Public library)

I didn’t realize that Michael Morpurgo’s Spring was the launch of a series of short nonfiction books on the seasons. McDermid writes a book a year, always starting it in early January. She evokes the Scottish winter’s “Janus-faced” character: cosy but increasingly storm-tossed. In few-page essays, she looks for nature’s clues, delves into childhood memories, and traverses the season through traditional celebrations as she has experienced them in Edinburgh and Fife: Hallowe’en, Bonfire Night, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve. The festivities are a collective way of taking the mind off of the season’s hardships, she suggests. I was amused by her mother’s recipe for soup, which she described as more of a “rummage” for whatever vegetables you have in the fridge. It was my first time reading McDermid and, while I don’t know that I will ever pick up one of her crime novels, this was pleasant. I reckon I’d read Bernardine Evaristo on summer and Kate Mosse on autumn, too. (Public library) ![]()

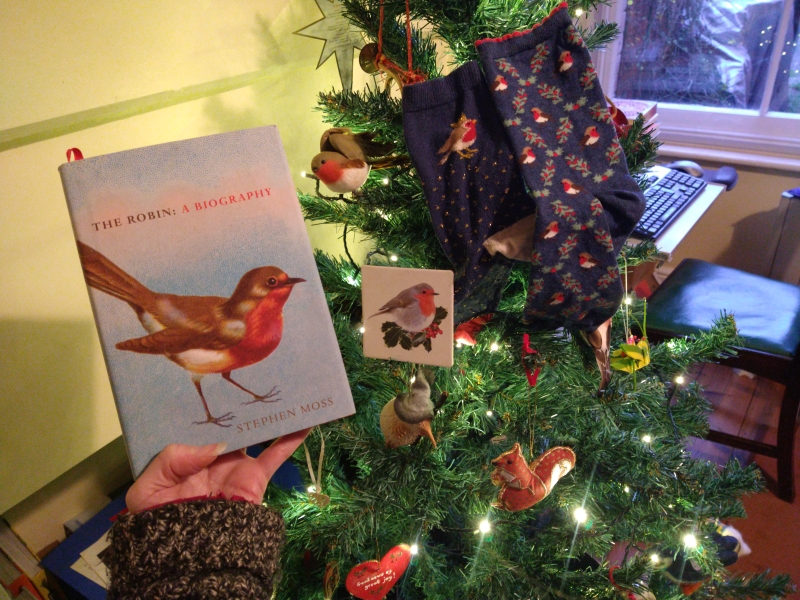

The Robin: A Biography – A Year in the Life of Britain’s Favourite Bird by Stephen Moss (2017)

I’ve also read Moss’s most recent bird monograph, The Starling. Both provide a thorough yet accessible introduction to a beloved species’ history, behaviour, and cultural importance. The month-by-month structure works well here: Moss’s observations in his garden and on his local patch lead into discussions of what birds are preoccupied with at certain times of year. Such a narrative approach makes the details less tedious. European robins are known for singing pretty much year-round, and because hardly any migrate – only 5%, it’s thought – they feel like constant companions. They are inquisitive garden guests, visiting feeders and hanging around to see if we monkey-pigs might dig up some juicy worms for them.

I’ve also read Moss’s most recent bird monograph, The Starling. Both provide a thorough yet accessible introduction to a beloved species’ history, behaviour, and cultural importance. The month-by-month structure works well here: Moss’s observations in his garden and on his local patch lead into discussions of what birds are preoccupied with at certain times of year. Such a narrative approach makes the details less tedious. European robins are known for singing pretty much year-round, and because hardly any migrate – only 5%, it’s thought – they feel like constant companions. They are inquisitive garden guests, visiting feeders and hanging around to see if we monkey-pigs might dig up some juicy worms for them.

(Last month, this friendly chap at an RSPB bird reserve near Exeter wondered if we might have a snack to share.)

Although we like to think we see the same robins year after year, that’s very unlikely. One in four robins found dead has been killed by a domestic cat; most die of old age and/or starvation within a year. Robin pairs raise one or two broods per year and may attempt a third if the weather allows, but that high annual mortality rate (62%) means we’re not overrun. Compared to other notable species, then, they’re doing well. There are loads of poems and vintage illustrations and, what with robins’ associations with Christmas, this felt like a seasonally appropriate read. At Christmas 2022 I read the very similar Robin by Helen F. Wilson, but this was more engaging. (Free from C’s former colleague) ![]()

Our small collection of Christmas robin paraphernalia.

&

The Robin & the Fir Tree by Jason Jameson (2020)

Based on a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, this lushly illustrated children’s book stars a restless tree and a faithful robin. The tree resents being stuck in one place and envies his kin who have been made into ships to sail the world. Although his friend the robin describes everything and brings souvenirs, he can’t see the funfair and the flora of other landscapes for himself. “Every season will be just the same. How I long for something different to happen!” he cries. Cue a careful-what-you-wish-for message. When men with axes come to chop down the fir tree and display him in the town square, he feels a combination of trepidation and privilege. Human carelessness turns his sacrifice to waste, and only the robin knows how to make something good out of the wreckage. The art somewhat outshines the story but this is still a lovely hardback I’d recommend to adults and older children. (Public library)

Based on a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, this lushly illustrated children’s book stars a restless tree and a faithful robin. The tree resents being stuck in one place and envies his kin who have been made into ships to sail the world. Although his friend the robin describes everything and brings souvenirs, he can’t see the funfair and the flora of other landscapes for himself. “Every season will be just the same. How I long for something different to happen!” he cries. Cue a careful-what-you-wish-for message. When men with axes come to chop down the fir tree and display him in the town square, he feels a combination of trepidation and privilege. Human carelessness turns his sacrifice to waste, and only the robin knows how to make something good out of the wreckage. The art somewhat outshines the story but this is still a lovely hardback I’d recommend to adults and older children. (Public library) ![]()

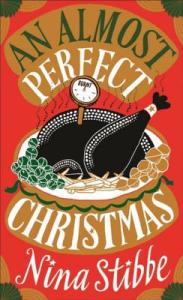

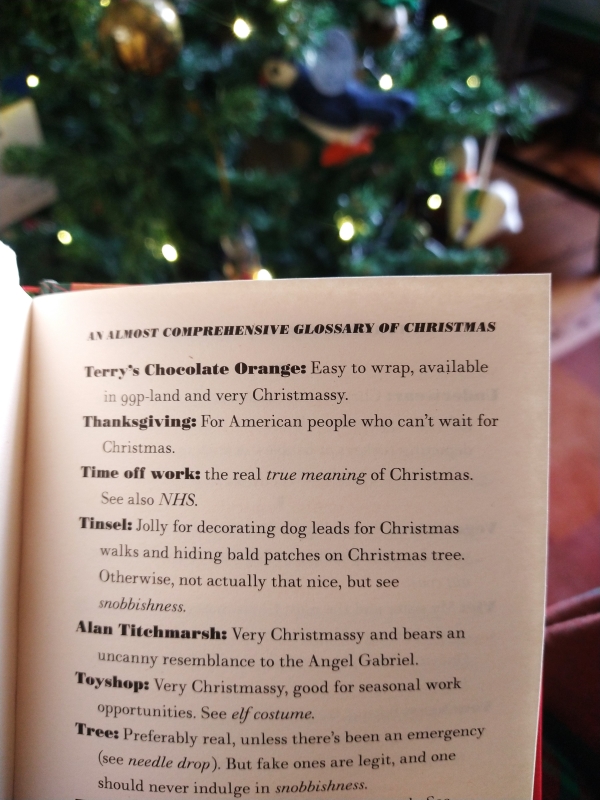

An Almost Perfect Christmas by Nina Stibbe (2017)

I reviewed this for Stylist magazine when it first came out and had fond memories of a witty collection I expected to dip into again and again. This time, though, Stibbe’s grumpy rants about turkey, family, choosing a tree and compiling the perfect Christmas party playlist fell flat with me. The four short stories felt particularly weak. I most recognized and enjoyed the sentiments in “Christmas Correspondence,” which is about the etiquette for round-robin letters and thank-you notes. The tongue-in-cheek glossary that closes the book is also amusing. But this has served its time in my collection and it’s off to the Little Free Library with it to, I hope, give someone else a chuckle on Christmas day. (Review copy)

I reviewed this for Stylist magazine when it first came out and had fond memories of a witty collection I expected to dip into again and again. This time, though, Stibbe’s grumpy rants about turkey, family, choosing a tree and compiling the perfect Christmas party playlist fell flat with me. The four short stories felt particularly weak. I most recognized and enjoyed the sentiments in “Christmas Correspondence,” which is about the etiquette for round-robin letters and thank-you notes. The tongue-in-cheek glossary that closes the book is also amusing. But this has served its time in my collection and it’s off to the Little Free Library with it to, I hope, give someone else a chuckle on Christmas day. (Review copy)

My original rating (2017): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

It’s taken me a long time to feel festive this year, but after a couple of book club gatherings and a load of brief community events for the Newbury Living Advent Calendar plus the neighbourhood carol walk, I think I’m finally ready for Christmas. (Not that I’ve wrapped anything yet.) I had a couple of unexpected bookish gifts arrive earlier in December. First, I won the 21st birthday quiz on Kim’s blog and she sent a lovely parcel of Australian books and an apt tote bag. Then, I was sent an early finished copy of Julian Barnes’s upcoming (final) novel, Departure(s). We didn’t trust Benny to be sensible around a real tree so got an artificial one free from a neighbour to festoon with non-breakable ornaments. He discovered the world’s comfiest blanket and spends a lot of time sleeping on it, which has been helpful.

Merry Christmas, everyone! I have a bunch of year-end posts in preparation. It’ll be a day off tomorrow, of course, but here’s what to expect thereafter:

Friday 26th: Reporting back on Most Anticipated Reads of 2025

Saturday 27th: Reading Superlatives

Sunday 28th: Best Backlist Reads

Monday 29th: Love Your Library

Tuesday 30th: Runners-Up

Wednesday 31st: Best Books of 2025

Thursday 1st: Final Statistics for 2025

Friday 2nd: Early Recommendations for 2026

Monday 5th: Most Anticipated Titles of 2026

Cover Love 2025

As I did in 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024, I’ve picked out some favourite book covers from the past year’s new releases. This time, I’ve read all of the books featured!

I’m drawn to flora and fauna on book covers; and to adapted artworks.

These two stood out for their psychedelic colour choices.

I like an unusual, elegant font. Can anyone identify the one below? I actually wonder if I would have chosen to read all four books had the font not attracted me.

Neat that the image and/or (most of the) title are vertically aligned – a rarer choice.

I found this paper cut-out striking, and loved how a cheekily torn matchbook gives the middle finger.

But my two favourite title and cover combinations of the year were:

- Calls May Be Recorded for Training and Monitoring Purposes by Katharina Volckmer – The cover is totally appropriate to the bonkers and raunchy contents (see my Shelf Awareness review – even though I technically reviewed the North American release I’m sticking with the full title and sex doll of the UK edition).

(Overall favourite:)

- Pan by Michael Clune – The cover perfectly captures the mood of this weird novel about a teenage boy who has panic attacks and muses about attributing them to the god Pan. The painting snippet is from The Drunkenness of Noah by Camillo Procaccini; but the eyes, look at those eyes!

What cover trends have you noticed this year? Which ones tend to grab your attention?

#NovNov25 Final Statistics & Some 2026 Novellas to Look Out For (Chapman, Fennelly, Gremaud, Miles, Netherclift & Saunders)

Novellas in November 2025 was a roaring success: In total, we had 50 bloggers contributing 216 posts covering at least 207 books! The buddy read(s) had 14 participants. If you want to take a look back at the link parties, they’re all here. It was our best year yet – thank you.

*For those who are curious, our most reviewed book was The Wax Child by Olga Ravn (4 reviews), followed by The Most by Jessica Anthony (3). Authors covered three times: Franz Kafka and Christian Kracht. Authors with work(s) reviewed twice: Margaret Atwood, Nora Ephron, Hermann Hesse, Claire Keegan, Irmgard Keun, Thomas Mann, Patrick Modiano, Edna O’Brien, Clare O’Dea, Max Porter, Brigitte Reimann, Ivana Sajko, Georges Simenon, Colm Tóibín and Stefan Zweig.*

I read and reviewed 21 novellas in November. I happen to have already read six with 2026 release dates, some of them within November and others a bit earlier for paid reviews. I’ll give a quick preview of each so you’ll know which ones you want to look out for.

The Pass by Katriona Chapman

Claudia Grace is a rising star in the London restaurant world: in her early thirties, she’s head chef at Alley. But she and her small team, including sous chef Lisa, her best friend from culinary school; and Ben, the innovative Black bartender, face challenges. Lisa has a young son and disabled husband, while Ben is torn between his love of gardening and his commitment to Alley. Claudia is more stressed than ever as she prepares for a competition. All three struggle with their parents’ expectations. A financial crisis comes out of nowhere, but the greater threat is related to motivation. I was drawn to this graphic novel for the restaurant setting, but it’s more about families and romantic relationships than food. Several characters look too alike or much younger or older than they’re supposed to, while there’s a sudden ending that suggests a sequel might follow. (Fantagraphics, Jan. 20) [184 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

Claudia Grace is a rising star in the London restaurant world: in her early thirties, she’s head chef at Alley. But she and her small team, including sous chef Lisa, her best friend from culinary school; and Ben, the innovative Black bartender, face challenges. Lisa has a young son and disabled husband, while Ben is torn between his love of gardening and his commitment to Alley. Claudia is more stressed than ever as she prepares for a competition. All three struggle with their parents’ expectations. A financial crisis comes out of nowhere, but the greater threat is related to motivation. I was drawn to this graphic novel for the restaurant setting, but it’s more about families and romantic relationships than food. Several characters look too alike or much younger or older than they’re supposed to, while there’s a sudden ending that suggests a sequel might follow. (Fantagraphics, Jan. 20) [184 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

The Irish Goodbye: Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly

I’ve also read Fennelly’s previous collection of miniature autobiographical essays, Heating & Cooling. She takes the same approach as in flash fiction: some of these 45 pieces are as short as one sentence, remarking on life’s irony, poignancy or brevity. Again and again she loops back to her sister’s untimely death (the title reference: “without farewells, you slipped out the back door of the party of your life”); other major topics are her mother’s worsening dementia, her happy marriage, her continuing 28-year-old friendships with her college roommates, the pandemic, and her ageing body. Every so often, Fennelly experiments with third- or second-person narration, as when she recalls making a perfect gin and tonic for Tim O’Brien. One of the most in-depth pieces revisits a lonely stint teaching in Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s. Returning to the town recently, she is astounded that so many recognize her and that a time she experienced as bleak is the stuff of others’ fond memories. I also loved the long piece that closes the collection, “Dear Viewer of My Naked Body,” about being one of the 12 people in Oxford, Mississippi to pose nude for a painter in oils. Brilliant last phrase: “Enjoy the bunions.” (W.W. Norton & Company, Feb. 24) [144 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

I’ve also read Fennelly’s previous collection of miniature autobiographical essays, Heating & Cooling. She takes the same approach as in flash fiction: some of these 45 pieces are as short as one sentence, remarking on life’s irony, poignancy or brevity. Again and again she loops back to her sister’s untimely death (the title reference: “without farewells, you slipped out the back door of the party of your life”); other major topics are her mother’s worsening dementia, her happy marriage, her continuing 28-year-old friendships with her college roommates, the pandemic, and her ageing body. Every so often, Fennelly experiments with third- or second-person narration, as when she recalls making a perfect gin and tonic for Tim O’Brien. One of the most in-depth pieces revisits a lonely stint teaching in Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s. Returning to the town recently, she is astounded that so many recognize her and that a time she experienced as bleak is the stuff of others’ fond memories. I also loved the long piece that closes the collection, “Dear Viewer of My Naked Body,” about being one of the 12 people in Oxford, Mississippi to pose nude for a painter in oils. Brilliant last phrase: “Enjoy the bunions.” (W.W. Norton & Company, Feb. 24) [144 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

Generator by Rinny Gremaud (2023; 2026)

[Trans. from French by Holly James]

“I was born in 1977 at a nuclear power plant in the south of South Korea,” the unnamed narrator opens. She and her mother then moved to Switzerland with her stepfather. In 2017, news of Korea’s plans to decommission the Kori 1 reactor prompts her to trace her birth father, who was a Welsh engineer on the project. As a way of “walking my hypotheses,” she travels to Wales, Taiwan (where he had a wife and family), Korea, and Michigan, his last known abode. In parallel, she researches the history of nuclear power. By riffing on the possible definitions of generation, this lyrical autofiction comments on creation and legacy. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Schaffner Press, Jan. 7) [197 pages] (PDF review copy)

“I was born in 1977 at a nuclear power plant in the south of South Korea,” the unnamed narrator opens. She and her mother then moved to Switzerland with her stepfather. In 2017, news of Korea’s plans to decommission the Kori 1 reactor prompts her to trace her birth father, who was a Welsh engineer on the project. As a way of “walking my hypotheses,” she travels to Wales, Taiwan (where he had a wife and family), Korea, and Michigan, his last known abode. In parallel, she researches the history of nuclear power. By riffing on the possible definitions of generation, this lyrical autofiction comments on creation and legacy. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Schaffner Press, Jan. 7) [197 pages] (PDF review copy) ![]()

Eradication: A Fable by Jonathan Miles

This taut, powerful fable pits an Everyman against seemingly insurmountable environmental and personal problems. Who wouldn’t take a job that involves “saving the world”? Adi, the antihero of Jonathan Miles’s fourth novel, is drawn to the listing not just for the noble mission but also for the chance at five weeks alone on a Pacific island. Santa Flora once teemed with endemic birds and reptiles, but many species have gone extinct because of the ballooning population of goats. He’s never fired a gun, but the mysterious “foundation” was so desperate it hired him anyway. It’s a taut parable reminiscent of T.C. Boyle’s When the Killing’s Done. My full Shelf Awareness review is here. (riverrun, 5 Feb. / Doubleday, Feb. 10) [176 pages] (Read via Edelweiss)

This taut, powerful fable pits an Everyman against seemingly insurmountable environmental and personal problems. Who wouldn’t take a job that involves “saving the world”? Adi, the antihero of Jonathan Miles’s fourth novel, is drawn to the listing not just for the noble mission but also for the chance at five weeks alone on a Pacific island. Santa Flora once teemed with endemic birds and reptiles, but many species have gone extinct because of the ballooning population of goats. He’s never fired a gun, but the mysterious “foundation” was so desperate it hired him anyway. It’s a taut parable reminiscent of T.C. Boyle’s When the Killing’s Done. My full Shelf Awareness review is here. (riverrun, 5 Feb. / Doubleday, Feb. 10) [176 pages] (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

Vessel: The shape of absent bodies by Dani Netherclift

One scorching afternoon in 1993, the author’s father and brother drowned while swimming in an irrigation channel near their Australia home. A joint closed-casket funeral took place six days later. Eighteen at the time, Netherclift witnessed her relatives’ disappearance but didn’t see their bodies. Must one see the corpse to have closure? she wonders. “The presence of absence” is an overarching paradox. There are lacunae everywhere: in her police statement from the fateful day; in her journal and letters from that summer. The contradictions and ironies of the situation defy resolution. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Assembly Press, Jan. 13) [184 pages] (PDF review copy)

One scorching afternoon in 1993, the author’s father and brother drowned while swimming in an irrigation channel near their Australia home. A joint closed-casket funeral took place six days later. Eighteen at the time, Netherclift witnessed her relatives’ disappearance but didn’t see their bodies. Must one see the corpse to have closure? she wonders. “The presence of absence” is an overarching paradox. There are lacunae everywhere: in her police statement from the fateful day; in her journal and letters from that summer. The contradictions and ironies of the situation defy resolution. Full Foreword review forthcoming. (Assembly Press, Jan. 13) [184 pages] (PDF review copy) ![]()

Vigil by George Saunders

Impossible not to set this against the exceptional Lincoln in the Bardo, focused as both are on the threshold between life and death. Unfortunately, the comparison is not favourable to Vigil. A host of the restive dead visit the dying to offer comfort at the end. Jill Blaine’s life was cut short when she was murdered by a car bomb in a case of mistaken identity. Her latest “charge” is K.J. Boone, a Texas oil tycoon who not only contributed directly to climate breakdown but also deliberately spread anti-environmentalist propaganda through speeches and a documentary. As he lies dying of cancer in his mansion, he’s visited by, among others, the spirits of the repentant Frenchman who invented the engine and an Indian man whose family perished in a natural disaster. I expected a Christmas Carol-type reckoning with climate past and future; in resisting such a formula, Saunders avoids moralizing – oblivion comes for the just and the unjust. However, he instead subjects readers to a slog of repetitive, half-baked comedic monologues. I remain unsure what he hoped to achieve with the combination of an irredeemable character and an inexorable situation. All this does is reinforce randomness and hopelessness, whereas the few other Saunders works I’ve read have at least reassured with the sparkle of human ingenuity. YMMV. (Bloomsbury / Random House, 27 Jan.) [192 pages] (Read via NetGalley)

Impossible not to set this against the exceptional Lincoln in the Bardo, focused as both are on the threshold between life and death. Unfortunately, the comparison is not favourable to Vigil. A host of the restive dead visit the dying to offer comfort at the end. Jill Blaine’s life was cut short when she was murdered by a car bomb in a case of mistaken identity. Her latest “charge” is K.J. Boone, a Texas oil tycoon who not only contributed directly to climate breakdown but also deliberately spread anti-environmentalist propaganda through speeches and a documentary. As he lies dying of cancer in his mansion, he’s visited by, among others, the spirits of the repentant Frenchman who invented the engine and an Indian man whose family perished in a natural disaster. I expected a Christmas Carol-type reckoning with climate past and future; in resisting such a formula, Saunders avoids moralizing – oblivion comes for the just and the unjust. However, he instead subjects readers to a slog of repetitive, half-baked comedic monologues. I remain unsure what he hoped to achieve with the combination of an irredeemable character and an inexorable situation. All this does is reinforce randomness and hopelessness, whereas the few other Saunders works I’ve read have at least reassured with the sparkle of human ingenuity. YMMV. (Bloomsbury / Random House, 27 Jan.) [192 pages] (Read via NetGalley) ![]()

#NovNov25 Catch-Up: Dodge, Garner, O’Collins, Sagan and A. White

As promised, I’m catching up on five novella-length works I finished in November. In fiction, I have an odd duck of a family story, a piece of autofiction about caring for a friend with cancer, a record of an affair, and a tale of settling two new cats into home life in the 1950s. And in nonfiction, a short book about the religious approach to midlife crisis.

Fup by Jim Dodge (1983)

I’d never heard of this but picked it up because of my low-key project of reading books from my birth year. After his daughter died in a freak accident, Grandaddy Jake Santee adopted his grandson “Tiny.” With that touch of backstory dabbed in, we’re in the northern California hills in 1978 with grandfather and grandson – now 99 and 22, respectively. Tiny builds fences, while Grandaddy is famous for his incredibly strong, home-distilled whiskey, “Ol’ Death Whisper.” One day, Tiny rescues a filthy creature from a posthole where it’s been chased by their nemesis, Lockjaw the wild boar. It turns out to be a duckling that grows into a hen mallard named Fup Duck (it’s a spoonerism…) who eats so much she’s too heavy to fly. Grandaddy plans to continue drinking and gambling indefinitely, but the hunt for Lockjaw – who he thinks may be a reincarnation of his Native American friend, Seven Moons – breaks the household apart. This was very weird: it starts out a mixture of grit (those grotesque Harry Horse drawings!) and Homer Hickam schmaltz and then goes full Jonathan Livingston Seagull. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) [89 pages]

I’d never heard of this but picked it up because of my low-key project of reading books from my birth year. After his daughter died in a freak accident, Grandaddy Jake Santee adopted his grandson “Tiny.” With that touch of backstory dabbed in, we’re in the northern California hills in 1978 with grandfather and grandson – now 99 and 22, respectively. Tiny builds fences, while Grandaddy is famous for his incredibly strong, home-distilled whiskey, “Ol’ Death Whisper.” One day, Tiny rescues a filthy creature from a posthole where it’s been chased by their nemesis, Lockjaw the wild boar. It turns out to be a duckling that grows into a hen mallard named Fup Duck (it’s a spoonerism…) who eats so much she’s too heavy to fly. Grandaddy plans to continue drinking and gambling indefinitely, but the hunt for Lockjaw – who he thinks may be a reincarnation of his Native American friend, Seven Moons – breaks the household apart. This was very weird: it starts out a mixture of grit (those grotesque Harry Horse drawings!) and Homer Hickam schmaltz and then goes full Jonathan Livingston Seagull. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) [89 pages] ![]()

The Spare Room by Helen Garner (2008)

Who knew there was such a market for novels about helping a friend through cancer treatment? Or maybe it’s just that I love them so much I home right in on them. As a work of autofiction – the no-nonsense narrator, Helen, gives her old friend Nicola a place to stay in Melbourne for several weeks while she undergoes experimental procedures – this is most like What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez (but I also had in mind Talk Before Sleep by Elizabeth Berg, We All Want Impossible Things by Catherine Newman, and Some Bright Nowhere by Ann Packer). Helen thinks The Theodore Institute peddles quack medicine, whereas Nicola is willing to shell out thousands of dollars for its coffee enemas and vitamin C infusions, even though they leave her terrifyingly fragile. Nicola is the only character who doesn’t acknowledge that her case is terminal. The pages turn effortlessly as Helen covers her frustration with Nicola, Nicola’s essential optimism, and the realities of living while dying. “Oh, I loved her for the way she made me laugh. She was the least self-important person I knew, the kindest, the least bitchy. I couldn’t imagine the world without her.” I’ll read more by Garner for sure. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [195 pages]

Who knew there was such a market for novels about helping a friend through cancer treatment? Or maybe it’s just that I love them so much I home right in on them. As a work of autofiction – the no-nonsense narrator, Helen, gives her old friend Nicola a place to stay in Melbourne for several weeks while she undergoes experimental procedures – this is most like What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez (but I also had in mind Talk Before Sleep by Elizabeth Berg, We All Want Impossible Things by Catherine Newman, and Some Bright Nowhere by Ann Packer). Helen thinks The Theodore Institute peddles quack medicine, whereas Nicola is willing to shell out thousands of dollars for its coffee enemas and vitamin C infusions, even though they leave her terrifyingly fragile. Nicola is the only character who doesn’t acknowledge that her case is terminal. The pages turn effortlessly as Helen covers her frustration with Nicola, Nicola’s essential optimism, and the realities of living while dying. “Oh, I loved her for the way she made me laugh. She was the least self-important person I knew, the kindest, the least bitchy. I couldn’t imagine the world without her.” I’ll read more by Garner for sure. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [195 pages] ![]()

Second Journey: Spiritual Awareness and the Mid-Life Crisis by Gerald O’Collins SJ (1978; 1995)

O’Collins, a Jesuit priest, sought a more constructive term than “midlife crisis” for the unease and difficult decisions that many face in their forties. He chooses instead the language of journeys, specifically one embarked upon because a previous way of life was no longer working. There are several types of triggers that O’Collins illustrates through brief case studies of famous individuals or anonymous acquaintances. The shift might be prompted by a sense of failure (John Wesley, Jimmy Carter), by literal exile (Dante), by falling in love (someone who left the priesthood to marry), by experiencing severe illness (John Henry Newman) or fighting in a war (Ignatius of Loyola), or simply by a longing for “something more” (Mother Teresa). But there are only two end points, O’Collins offers: a new place or situation; or a fresh appreciation of the old one – he quotes Eliot’s “to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” This is practical and relatable, but light on actual advice. It also pales by comparison to Richard Rohr’s more recent work on spirituality in the different stages of life (especially in Falling Upward). (Free from a church member’s donations) [100 pages]

O’Collins, a Jesuit priest, sought a more constructive term than “midlife crisis” for the unease and difficult decisions that many face in their forties. He chooses instead the language of journeys, specifically one embarked upon because a previous way of life was no longer working. There are several types of triggers that O’Collins illustrates through brief case studies of famous individuals or anonymous acquaintances. The shift might be prompted by a sense of failure (John Wesley, Jimmy Carter), by literal exile (Dante), by falling in love (someone who left the priesthood to marry), by experiencing severe illness (John Henry Newman) or fighting in a war (Ignatius of Loyola), or simply by a longing for “something more” (Mother Teresa). But there are only two end points, O’Collins offers: a new place or situation; or a fresh appreciation of the old one – he quotes Eliot’s “to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” This is practical and relatable, but light on actual advice. It also pales by comparison to Richard Rohr’s more recent work on spirituality in the different stages of life (especially in Falling Upward). (Free from a church member’s donations) [100 pages] ![]()

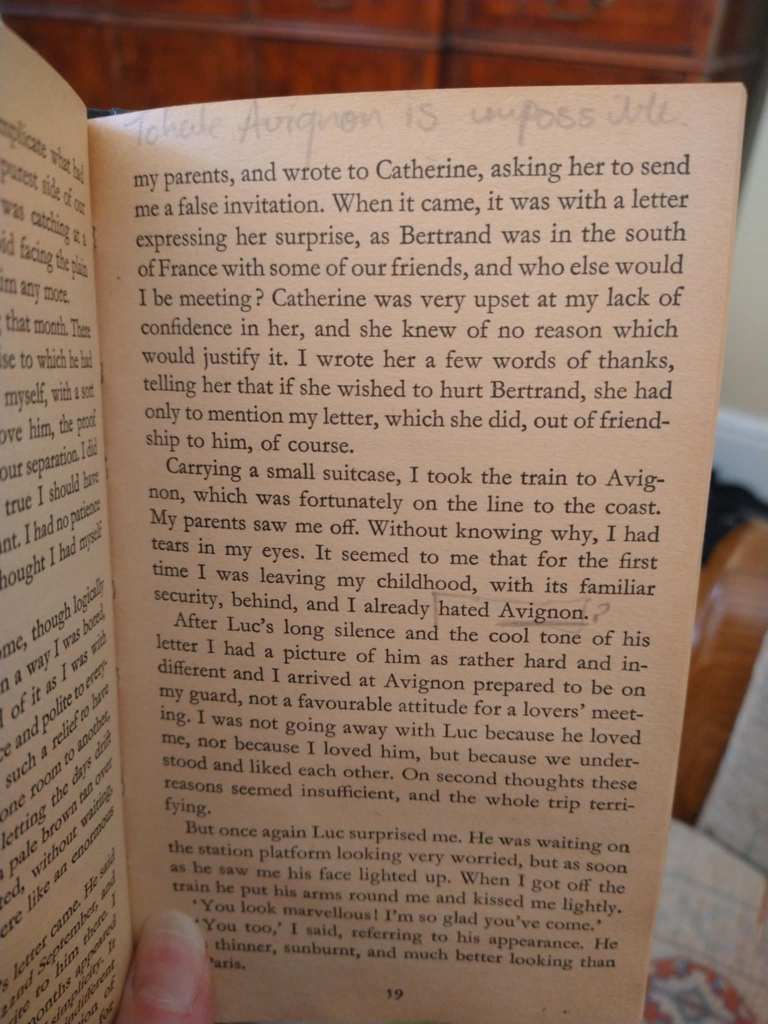

A Certain Smile by Françoise Sagan (1956)

[Translated from French by Irene Ash]

Law student Dominique is lukewarm on her boyfriend Bertrand and starts seeing his married uncle, Luc, instead. The high point is when they manage to go on a ‘honeymoon’ trip of several weeks to Avignon. Both Bertrand and Luc’s wife, Françoise, eventually find out, but everyone is very grown-up about it. The struggle is never external so much as within Dominique to accept that she doesn’t mean as much to Luc as he does to her, and that the relationship will only be a little blip in her early adulthood. I found this a disappointment compared to Bonjour Tristesse and Aimez-Vous Brahms – it really is just the story of an affair; nothing more – but Sagan is always highly readable. I read this in two days, a big section of it on a chilly beach in Devon. In its frank, cool assessment of relationship dynamics, this felt like a model for Sally Rooney. I had to laugh at the righteously angry and rather ungrammatical marginalia below (“To hate Avignon is unpossible”). (University library) [112 pages]

Law student Dominique is lukewarm on her boyfriend Bertrand and starts seeing his married uncle, Luc, instead. The high point is when they manage to go on a ‘honeymoon’ trip of several weeks to Avignon. Both Bertrand and Luc’s wife, Françoise, eventually find out, but everyone is very grown-up about it. The struggle is never external so much as within Dominique to accept that she doesn’t mean as much to Luc as he does to her, and that the relationship will only be a little blip in her early adulthood. I found this a disappointment compared to Bonjour Tristesse and Aimez-Vous Brahms – it really is just the story of an affair; nothing more – but Sagan is always highly readable. I read this in two days, a big section of it on a chilly beach in Devon. In its frank, cool assessment of relationship dynamics, this felt like a model for Sally Rooney. I had to laugh at the righteously angry and rather ungrammatical marginalia below (“To hate Avignon is unpossible”). (University library) [112 pages] ![]()

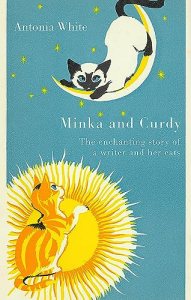

Minka and Curdy by Antonia White; illus. Janet and Anne Johnstone (1957)

After Mrs Bell’s formidable cat Victoria dies, she hankers to get a new kitten to keep her company – she works at home as a writer. She finds herself greeting all the neighbourhood cats and, in her enthusiasm to help a ‘stray’, accidentally overfeeds someone else’s pet with fresh fish. Her heart is set on a marmalade kitten, so she reserves one from an impending litter in Kent. But then the opportunity to take on a beautiful young female Siamese cat, for free, comes her way, and though she feels guilty about the ginger tom she’s been promised, she adopts Minka anyway. When Coeur de Lion (“Curdy”) arrives a few weeks later, her challenge is to get the kitties to coexist peacefully in her London flat. This reminded me so much of myself back in February and March, when I was so glum over losing Alfie that we rushed into adopting a giant kitten who has been a bit much for us. But we’re already contemplating getting Benny a little sister or two, so I read with interest to see how she made it happen. Well, this is fiction, so it starts out fraught but then is somewhat magically fine. No matter – White writes about cats’ antics and personalities with all the warmth and delight of Derek Tangye, Doreen Tovey and the like, and this 2023 Virago reprint is adorable. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [113 pages]

After Mrs Bell’s formidable cat Victoria dies, she hankers to get a new kitten to keep her company – she works at home as a writer. She finds herself greeting all the neighbourhood cats and, in her enthusiasm to help a ‘stray’, accidentally overfeeds someone else’s pet with fresh fish. Her heart is set on a marmalade kitten, so she reserves one from an impending litter in Kent. But then the opportunity to take on a beautiful young female Siamese cat, for free, comes her way, and though she feels guilty about the ginger tom she’s been promised, she adopts Minka anyway. When Coeur de Lion (“Curdy”) arrives a few weeks later, her challenge is to get the kitties to coexist peacefully in her London flat. This reminded me so much of myself back in February and March, when I was so glum over losing Alfie that we rushed into adopting a giant kitten who has been a bit much for us. But we’re already contemplating getting Benny a little sister or two, so I read with interest to see how she made it happen. Well, this is fiction, so it starts out fraught but then is somewhat magically fine. No matter – White writes about cats’ antics and personalities with all the warmth and delight of Derek Tangye, Doreen Tovey and the like, and this 2023 Virago reprint is adorable. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [113 pages] ![]()

I also had a few DNFs last month:

- The Book of Colour by Julia Blackburn (1995) seemed a good bet because I’ve enjoyed some of Blackburn’s nonfiction and it was on the Orange Prize shortlist. But after 60 pages I still had no idea what was going on amid the Mauritius-set welter of family history and magic realism. (Secondhand – Bas Books charity shop, 2022)

- A Single Man by Christopher Isherwood (1964) lured me because I’d so loved Goodbye to Berlin and I remember liking the Colin Firth film. But this story of an Englishman secretly mourning his dead partner while trying to carry on as normal as a professor in Los Angeles was so dreary I couldn’t persist. (Public library)

- Night Life: Walking Britain’s Wild Landscapes after Dark by John Lewis-Stempel (2025) – JLS could write one of these mini nature volumes in his sleep. (Maybe he did with this one, actually?) I’d rather one full-length book from him every few years than bitty, redundant ones annually. (Public library)

- Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen by P.G. Wodehouse (1974) – I’ve read one Jeeves & Wooster book before and enjoyed it well enough. This felt inconsequential, so as I already had way too many novellas on the go I sent it back whence it came. (Little Free Library)

Final statistics for #NovNov25 coming up tomorrow!

Literary Wives Club: The Soul of Kindness by Elizabeth Taylor (1964)

(With apologies for today’s multiple posts!)

This was my fifth time reading Elizabeth Taylor. It’s a later novel of hers: the ninth of 12. As per usual, there’s an ensemble cast, but this time I had some trouble keeping the characters straight and finding enough sympathy for all of them. There are a dozen main players if you count housekeepers and neighbours. The opening scene is Flora’s wedding to Richard. She’s the title character: beautiful and well-meaning yet sometimes thoughtless. As she grows into the roles of wife and mother, Flora believes everyone should follow her into marriage.

This was my fifth time reading Elizabeth Taylor. It’s a later novel of hers: the ninth of 12. As per usual, there’s an ensemble cast, but this time I had some trouble keeping the characters straight and finding enough sympathy for all of them. There are a dozen main players if you count housekeepers and neighbours. The opening scene is Flora’s wedding to Richard. She’s the title character: beautiful and well-meaning yet sometimes thoughtless. As she grows into the roles of wife and mother, Flora believes everyone should follow her into marriage.

Although as good as gold, she had inconvenient plans for other people’s pleasure, and ideas differing from her own she was unable to imagine.

Her interfering can be comical – she doesn’t realize Patrick is homosexual, so her attempt to match-make between him and her friend Meg is futile.

If she could get Meg settled, Flora had decided, she herself would be quite happy, but her friend thought she went about it in strange ways and wondered what, if anything, Flora knew about people.

When she convinces her father-in-law, Percy, to marry his mistress, Barbara, it’s the wrong thing for them. (“I think we are very well as we are, Percy,” Ba had said.) By ignoring Meg’s little brother Kit’s crush on her and encouraging his hopeless dream of acting, Flora nearly precipitates a tragedy – and Kit’s lover decides to let her know about her misstep.

I got hints of Emma so was pleased to see that comparison made in Philip Hensher’s introduction, in which he considers The Soul of Kindness in the context of the English “novel of community.” Flora herself somewhat fades into the background as we spend time rotating through the other characters in pairs. I found Flora silly and stubborn but not deserving of others’ ire. I felt most for Richard and for her mother, Mrs Secretan, both of whom she unfairly underestimates and sidelines.

This wasn’t one of my favourite Taylors – those are Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont, which I’ve read twice, and In a Summer Season – but she always writes with grace and psychological acuity. Here I loved a description of the fog – “It’s disorganising, like snow. It makes a different world” – and the fact that the book starts and ends with throwing crumbs to birds. Flora’s pet doves must be a symbol of something: the peace she tries to keep but unwittingly disturbs? In any case, the next time you find a book a slog, here’s her diplomatic strategy for talking about it:

she said that she was taking the books in tiny sips, à petites doses, as Henry James wrote when he was up to the same trick – as if it were the most precious wine. That meant that she was bogged down in it.

(Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury?)

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Marriage is not a solution to a problem. (Especially if that problem is loneliness.) Some people aren’t the marrying kind, for whatever reason. Being a spouse can be one aspect of a person’s identity, but it’s dangerous when it becomes defining – this is probably the single common moral I’d draw from all that we’ve read for the club.

See Becky’s, Kate’s and Kay’s reviews, too! (Naomi is taking a break.)

Coming up next, in March: Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell.

Novellas New to My TBR in #NovNov25

Somehow the rest of November flew away and all my best-laid plans for reviewing my preposterous stack of novellas fell by the wayside. As usual, I enthusiastically started a dozen when I should have just focused on three or four; it is ever thus. We spent the weekend visiting friends and it was also C’s birthday yesterday, so there wasn’t much time for reading. However, I managed to finish another five novellas by the 30th to review later in the week.

I will keep the link-up open through Saturday the 6th for belated reviews and catch-up posts and on Sunday the 7th I will post final statistics for the year’s challenge.

Here are the novellas I’ve added to my TBR this month:

Before the Leaves Fall by Clare O’Dea, reviewed by both Cathy and Susan – Set in Switzerland, it has an assisted dying theme, which always attracts me. It’s also published by the indie Fairlight Books.

Before the Leaves Fall by Clare O’Dea, reviewed by both Cathy and Susan – Set in Switzerland, it has an assisted dying theme, which always attracts me. It’s also published by the indie Fairlight Books.

This one is nonfiction:

Middlemarch and the Imperfect Life by Pamela Erens (from the Bookmarked series), spotted by chance on Liz’s wish list. I do love a memoir that responds to another work of literature.

Middlemarch and the Imperfect Life by Pamela Erens (from the Bookmarked series), spotted by chance on Liz’s wish list. I do love a memoir that responds to another work of literature.

And these two are 2026 releases that are on my radar as review books…

Who Killed Bambi? by Monika Fagerholm (for Foreword Reviews) is about the aftermath of a teen gang rape in Helsinki.

Who Killed Bambi? by Monika Fagerholm (for Foreword Reviews) is about the aftermath of a teen gang rape in Helsinki.

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico (for Shelf Awareness) is a response to her spouse transitioning.

Men I Hate: A Memoir in Essays by Lynette D’Amico (for Shelf Awareness) is a response to her spouse transitioning.

Whew, four isn’t so overwhelming!

I gave some initial thoughts about the book

I gave some initial thoughts about the book

This is a mash-up of the campus novel, the Victorian pastiche, and the time travel adventure. Ariel Manto is a PhD student working on thought experiments. Inciting incidents come thick and fast: her supervisor disappears, the building that houses her office partially collapses as it’s on top of an old railway tunnel, and she finds a copy of Thomas Lumas’s vanishingly rare The End of Mr. Y in a box of mixed antiquarian stock going for £50 at a secondhand bookshop. Rumour has it the book is cursed, and when Ariel realises that the key page – giving a Victorian homoeopathic recipe for entering the “Troposphere,” a dream/thought realm where one travels through time and space – has been excised, she knows the quest has only just begun. It will involve the book within a book, Samuel Butler novels, a theologian and a shrine, lab mice plus the God of Mice, and a train line whose destinations are emotions.

This is a mash-up of the campus novel, the Victorian pastiche, and the time travel adventure. Ariel Manto is a PhD student working on thought experiments. Inciting incidents come thick and fast: her supervisor disappears, the building that houses her office partially collapses as it’s on top of an old railway tunnel, and she finds a copy of Thomas Lumas’s vanishingly rare The End of Mr. Y in a box of mixed antiquarian stock going for £50 at a secondhand bookshop. Rumour has it the book is cursed, and when Ariel realises that the key page – giving a Victorian homoeopathic recipe for entering the “Troposphere,” a dream/thought realm where one travels through time and space – has been excised, she knows the quest has only just begun. It will involve the book within a book, Samuel Butler novels, a theologian and a shrine, lab mice plus the God of Mice, and a train line whose destinations are emotions.