“Under the hieroglyphical similitude of tropes and figures?”

However, Putnam faced a couple of challenges in replying. First, if he appeared to be flying off the handle, that would simply validate what the “Freeholder” had written.

Second, Putnam wasn’t a highly educated man, and in particular his spelling and punctuation were even more irregular than the eighteenth-century norm.

Even Putnam’s biographers acknowledge that he probably had help in shaping his reply in the 7 October 1774 Connecticut Gazette of New London, either from a friend or from printer Timothy Green. Because it doesn’t look like his usual writing.

The preface reads:

Mr. GREEN,The first line of the ensuing essay makes clear what it was really responding to: “In Mr. [Hugh] Gaine’s New-York Gazette of the 12th of September…”

As my letter to Capt. [Aaron] Cleveland, wrote in consequence of the late alarm, has circulated far and wide, and made unfavourable impressions on the minds of some, ’tis desired that you and the several printers in the other colonies upon the continent, would give the following piece a place in your paper, and you will oblige

Your humble Servant,

ISRAEL PUTNAM.

POMFRET, 3d. October 1774.

Putnam described how the rumor of a British military attack on Boston had reached him through “Capt. Keyes”—most likely Stephen Keyes (1717–1788, gravestone shown above courtesy of Find a Grave). Keyes had heard the news from “Capt. Clarke of Woodstock,” who heard from his son in Dudley, Massachusetts, who heard from an Oxford man named Wilcot, who heard from his father and also found confirmation in Grafton.

With “only four gentlemen,” Putnam rode toward Boston, traveling “about thirty miles from my house.” In Douglas, Massachusetts, the party met the local militia captain, probably Caleb Hill (1716–1788), who with his company had just returned from their own march to “within about thirty miles of Boston.” Having thus learned that the earlier report was false, Putnam returned home, spreading the new word.

Putnam posited that the false alarm started with Customs Commissioner Benjamin Hallowell having “informed the army that he had killed one man and wounded another” while escaping from Cambridge. Hallowell’s own account of the “Powder Alarm” said nothing of the sort.

As for presenting himself as a gentleman in prose, Putnam acknowledged that he’d written his letter passing on that misinformation in haste and not in high style; he said he “aimed at nothing but plain matters of fact, as they were delivered to him.”

But Putnam also showed himself capable of deploying complex sentences and classical allusions in response to the “New-York Freeholder”:

Paying all due defference to this author’s learning, and his undoubted acquaintance with the rules of grammar and criticism, I would beg leave to ask him, whether he does not betray a total want of the feelings of humanity, if he supposes in the midst of confusion, when the passions are agitated with a real belief of thousands of their fellow countrymen being slain, & the inhabitants of a whole city just upon the eve of being made a sacrifice by the rapine and fury of a merciless soldiery, and their city laid in ashes by the fire of ships of war, he or any one else could set down under the possession of a calmness of soul becoming a Roman senator, and attend to all the rules of composition, in writing a letter, to make a representation of plain matters of facts, under the hieroglyphical similitude of tropes and figures? . . .Well, when he put it that way…

Now I submit it to the determination of every candid unprejudiced reader, whether my conduct in writing the aforementioned letter, merits the imputation of imprudence asserted by said writer; or whether they would have had me tamely set down, and been a spectator to the unhuman sacrifice of my friends and fellow-countrymen, or (in other words) Nero like, have set down and fiddled, while I really supposed Boston was in flames, or exerted myself for their relief?

TOMORROW: Who was the “New-York Freeholder”?

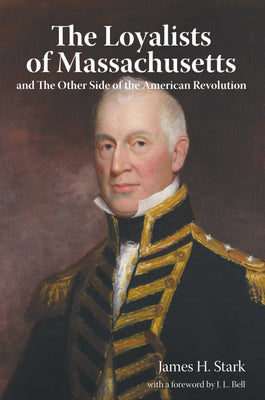

.png/500px-Morgan_Lewis_(portrait_by_Henry_Inman).png)