Ho Xuan Huong (胡春香; 1772–1822) was a Vietnamese poet born at the end of the Lê dynasty. The facts of her life are difficult to verify. It seems that she was born in Nghệ An Province and moved to Hanoi while still a child. Her father, Hồ Phi Diễn, died when she was a young girl. While there is some dispute as to her father, her mother, whose given name was Hà, remarried and became a second wife , or concubine, to a fresh husband, albeit a concubine of high rank. There are some indications that Ho Xuan Huong ran a tea shop where she composed, when asked, impromptu poems that were subtle and witty. She probably received an education in the classical literature of her time, as she was adept at using classical Chinese forms.

She is believed to have married twice as her poems refer to two different husbands: Vinh Tuong (a local official) and Tong Coc (a slightly higher level official). She was the second-rank wife of Tong Coc, – in other words, a concubine – a man she refers to as Mister Toad in her funeral elegy. Hers was a marital role that she clearly disdained (like the maid/but without the pay). However, her second marriage did not last long as her husband was executed for bribery just six months after the wedding. It is not known whether or not they had children. After his death, she made her living as a teacher and traveled widely throughout northern Vietnam. An official record of that time describes her as well-known as a talented woman of literature and politics. Little is known about her life, but she is the subject of many popular stories. One such story illustrates her sense of humour; upon falling over, it is said that she threw off her embarrassment, claiming: I stretch my arms to learn the height of the sky; I spread my legs to measure the earth, a typical example of the irreverent frank sexual humour, often consisting of double entendres, for which her poetry is noted.

She spent the last years of her life in a small house near the West Lake in Hanoi.

NÔM AND THE POETRY OF HO XUAN HUONG

Ho Xuan Huong has been called “the Queen of Nôm Poetry” and is considered one of the unique poets of Vietnamese literature. While many of her works have been lost, those poems of hers still in circulation are mainly oral Nôm poems. Rather than use Chinese, the language of the mandarin elite, she chose to write in Nôm, a form of writing system that represented not only Vietnamese speech but also the aphorisms and speech habits of the common people. Nôm assigns Vietnamese phonemes to traditional Chinese characters, but according to John Balaban, other Chinese characters are retained for semantic value, so that Nôm uses about twice as many characters as Chinese. Examples of the poems in Nôm are shown above some of the translations below.

As for her subject matter, most of her poems are written from a female, and what may nowadays be called a feminist, perspective. Writing in a society dominated by men, Ho’s poetry, using deceptively simple images, presents explicit and humorous portrayals of sexual desire, women’s bodies, power relations in a patriarchal society, and the stifling nature of tradition. She writes continually about the corruption of politicians (her second husband was executed for bribery), the decadence of Buddhist monks, the difficulties and degradations of life as a concubine, the inferior status of woman and the desire for love. She also wrote about loneliness and landscape.

However, what accounts for the success and endurance of her poetry is her wicked sense of humour, reflected in a constant use of scurrilous puns or double entendres. Pat Valdata, in her essay Reading Between the Lines: Ho Xuan Huong, the Queen of Nôm Poetry, explains this clearly: The most notable and notorious aspect of Ho Xuan Huong’s work is the sexual innuendo that until recently made her poems too racy for “good girls” to read. Probably her most famous poem is “Jackfruit”:

My body is like the jackfruit on the branch:

my skin is coarse, my meat is thick.

Kind sir, if you love me, pierce me with your stick.

Caress me and sap will slicken your hands.

Balaban’s translation above shows on a literal sense the practice of impaling a jackfruit on a stick to ripen it, but it is impossible to read this poem without seeing the clear reference to the sexual act in the final two lines. Many of her poems, including some of the brief poems printed below, indulge in a similar “smutty” innuendo. (Consider, for example, Male Member.) While a modern reader may not be upset by such double-edged humour, many of her readers in the past may have been shocked by her daring to question, in such a defiant and devious way, the norms of a patriarchal society. It is interesting to note that before the 1960’s, although her work was well known in Vietnam, it did not appear on the school curriculum, as it was considered too vulgar by male critics.

TRANSLATING HO XUAN HUONG

The earliest surviving hand-copied volume of the poems of Ho Xuan Huong was commissioned in 1893 by a Frenchman, Antony Landes. The earliest printed collection of her poems was produced in 1909. In 1968 she reached a wider audience when her poetry was translated into French by Maurice Durand. In 1975 some of her poems appeared in a collection of Vietnamese poetry published by Knopf. But it was the publication in 2000 of John Balaban’s book-length translation, Spring Essence: The Poetry of Ho Xuan Huong, that brought her work to the attention of English-speaking readers. Balaban spent ten years translating the forty-nine poems collected in the book. The cover (see right) depicts a bare-breasted woman, hiding her face behind a gong. Introducing her work John Balaban writes that for her erotic attitudes, Hồ Xuân Hương turned to the common wisdom alive in peasant folk poetry and proverbs, and that common people […] could hear in her verse echoes of their folk poetry, proverbs, and village common sense. The book features a “tri-graphic” presentation of English translations alongside both the modern Romanized Vietnamese alphabet and the original nearly extinct ideographic Nôm script, the hand-drawn calligraphy in which Hồ Xuân Hương originally wrote her poems. Some of these are included below.

These translations of Ho Xuan Huong have produced some disputes. The poet Linh Dinh attacked John Balaban in a blog post “Me So Horny” for inaccuracies of scholarship. Linh Dinh wrote that legends, myths, lies and general bullshit abound in Vietnam and he accused Balaban of poor ethnographic practices. He also mocked Balaban’s pronunciation of Vietnamese: When my wife and I heard him perform some Vietnamese poems in North Carolina in 2004, we couldn’t understand, literally, a single word. However, an anonymous contributor to the post dissented: he has literally brought Vietnamese literature to a global stage (do you know how much attention “Spring Essence” has received?) as well as starting a movement to preserve the dying “Nom” script. As well as criticizing the Balaban translations, Linh Dinh also includes his own translations of eight of the poems.

Further translations, this time by Marilyn Chin’s appeared in 2008 issue of Poetry. When I came across Ho Xuan Huong’s lyrics, I immediately recognized the structure of the Chinese quatrain—four-lined and eight-lined poems; seven-character lines; parallelism; reduplication of characters for sonic emphasis or refrain; set internal and external rhyme and tonal patterns. I recognized the well-worn symbols—the ripe fruit and the dumpling representing the woman’s body. Five of her translations appear on the Poetry Foundation site. These produced an immediate backlash from John Balaban’s publisher, Joseph Bednarik of the Copper Canyon Press, who wrote to the editor of Poetry: I don’t see how Chin’s versions add depth or nuance to the work. Frankly, they read like someone noodling around in the margins of someone else’s book. (Poetry, June 2008). Responding in the same issue, Chin accused the publisher of racism and cultural imperialism: Perhaps Bednarik and his press believe that the white male patriarchy must forever colonize the translation of Asian poetry. (Poetry, June 2008). Entering the fray, John Balaban criticized her translations, accusing her, in turn of cultural imperialism, given Vietnam’s troubled ancient and recent history with China. (Poetry, July/August 2008).

The following year, after seeing Marilyn Chin’s translations in the April issue of Poetry, Balaban’s publisher, Joseph Bednarik, wrote to the editor: “I don’t see how Chin’s versions add depth or nuance to the work. Frankly, they read like someone noodling around in the margins of someone else’s book” (Poetry, June 2008). In her response in the same issue, Chin then accused Bednarik of racism and cultural imperialism: “Perhaps Bednarik and his press believe that the white male patriarchy must forever colonize the translation of Asian poetry” (Poetry, June 2008). This response prompted Balaban to write his own letter critical of her translations and accusing her of cultural imperialism as well “[g]iven Vietnam’s troubled ancient and recent history with China” (Poetry, July/August 2008)

As Pat Valdata says, on her post on The Mezzo Cammin site: One can’t help but imagine that Ho Xuan Huong would be delighted to know that her work still inspires heated debate.

Other translators have proved less contentious. Mỹ Ngọc Tô writes: When I discovered her work several years ago, I immediately felt in kinship with the feminine strength, eroticism, wisdom, and serenity of her voice. After reading existing English translations, I wanted to create versions guided by my own understanding of and love for the Vietnamese language.

On The HyperTexts site, which he curates, Michael R Burch provides what he modestly calls a loose translation/interpretation of twelve poems by Ho Xuan Huong. Her verse, he writes, replete with nods, winks, sexual innuendo and a rich eroticism, was shocking to many readers of her day and will probably remain so to some of ours. Huong has been described as “the candid voice of a liberal female in a male-dominated society.” Her output has been called “coy, often bawdy lyrics.” I would add “suggestive to graphic.” More of his own original poetry and more of what he calls “loose translations” of other poets are available on the Michael R. Burch post on this blog.

I have included a variety of translations below without selecting a favourite. Should you wish to discuss these or to select a favourite translator, use the comment box below.

Brief Poems by Ho Xuan Huong

詠屋𧋆

博媄生𫥨分屋𧋆

𣎀𣈜粦𨀎盎𦹵灰

君子固傷辰扑𧞣

吀停𪭟𢭴魯𦟹碎

River Snail

Fate and my parents shaped me like a snail,

day and night wandering marsh weeds that smell foul.

Kind sir, if you want me, open my door.

But please don’t poke up into my tail.

John Balaban

***

Snail

Mother and father gave birth to a snail

Night and day I crawl in smelly weeds

Dear prince, if you love me, unfasten my door

Stop, don’t poke your finger up my tail!

Marylin Chin

***

The Snail

My parents have brought forth a snail,

Night and day among the smelly grass.

If you love me, peel off my shell,

Don’t wiggle my little hole, please.

Linh Dinh

***

The Snail

My parents produced a snail,

Night and day it slithers through slimy grass.

If you love me, remove my shell,

But please don’t jiggle my little hole!

Michael R. Burch

餅㵢

身㛪辰𤽸分㛪𧷺

𠤩浽𠀧沉買渃𡽫

硍湼默油𢬣几揑

𦓡㛪刎𡨹𬌓𢚸𣘈

The Floating Cake

My body is white; my fate, softly rounded,

rising and sinking like mountains in streams.

Whatever way hands may shape me,

at center my heart is red and true.

John Balaban

***

Floating Sweet Dumpling

My body is powdery white and round

I sink and bob like a mountain in a pond

The hand that kneads me is hard and rough

You can’t destroy my true red heart

Marylin Chin

***

Floating Sweet Dumpling

My powdered body is white and round.

Now I bob. Now I sink.

The hand that kneads me may be rough,

But my heart at the center remains untouched.

Michael R. Burch

***

The cake that drifts in water

My body is both white and round

In water I may sink or swim.

The hand that kneads me may be rough—

I still shall keep my true-red heart.

Huynh Sanh Thong

***

Sweet Rice Ball, Afloat

My body is both white and round

Rising, then sinking in these mountain waters

I’ll rip apart despite men’s molding hands

Nonetheless, my heart remains red and pure

Mỹ Ngọc Tô

菓

身㛪如菓𨕭𣘃

䏧奴芻仕脢奴𠫅

君子固腰辰㨂𱣳

吀停緍𢱖澦𫥨𢬣

Jackfruit

My body is like the jackfruit on the branch:

my skin is coarse, my meat is thick.

Kind sir, if you love me, pierce me with your stick.

Caress me and sap will slicken your hands.

John Balaban

***

The Jackfruit

My body is like a jackfruit on a branch,

With a rugged skin and thick flesh,

But if it pleases you, drive the stake.

Don’t just fondle, or the sap

Will stain your fingers.

Linh Dinh

***

Jackfruit

My body is like a jackfruit swinging on a tree

My skin is rough, my pulp is thick

Dear prince, if you want me pierce me upon your stick

Don’t squeeze, I’ll ooze and stain your hands

Marylin Chin

***

The Breadfruit or Jackfruit

My body’s like a breadfruit ripening on a tree:

My skin coarse, my pulp thick.

My lord, if you want me, pierce me with your stick,

But don’t squeeze or the sap will sully your hands!

Michael R. Burch

***

The Jackfruit

I am like a jackfruit on the tree.

To taste you must plug me quick, while fresh:

the skin rough, the pulp thick, yes,

but oh, I warn you against touching —

the rich juice will gush and stain your hands

Nguyen Ngoc Bich

***

Jackfruit

I swell like a late summer jackfruit.

My skin roughens, the pulp of my body so thick.

I wait to be speared and wanted.

If squeezed, I’ll leave my colour on your hands.

Natalie Linh Bolderston

𨔈花

㐌啐𨔈花沛固𨅹

𨅹𨖲𠤆礒痗昌

梗羅梗俸援𢫈𢪱

葻𠃩葻撑底論漂

Picking Flowers

If you want to pick flowers, you have to hike.

Climbing up, don’t worry about your weary bones.

Pluck the low branches, pull down the high.

Enjoy alike the spent blossoms, the tight bubs.

John Balaban

***

Wasps

Where and why are you wandering, foolish wasps?

Come, your big sister will teach you to compose!

Silly baby wasps suckle from rotting stamens;

Horny ewes butt fences when there’s freedom in the gaps.

Michael R. Burch

***

Wasps

Where are you wandering to, little fools

Come, big sister will teach you how to write verse

Itchy little wasps sucking rotting flowers

Horny baby lambkins butting gaps in the fence

Marylin Chin

***

詠陽物

博媄生𫥨本拯𢤞

最雖空眜𠓇欣畑

頭隊𥶄䏧𤍶䉅𧺃

𨉞㧅備磾𢷀韜顛

Male Member

New born, it wasn’t so vile. But, now, at night,

even blind it flares brighter than any lamp.

Soldierlike, it sports a reddish leather hat,

Musket balls sagging the bag down below.

John Balaban

***

To a Couple of Students Who Were Teasing Her

Where are you going, my dear little greenhorns?

Here, I’ll teach you how to turn a verse or two

Young drones sucking at withered flowers,

Little goats brushing horns against a fence.

Marylin Chin

***

***

New Year Couplet

On the thirtieth night, we seal the sky and soil against demons,

then unlatch the first morning, let every woman gather spring in her arms.

Natalie Linh Bolderston

***

Screw You!

Screw the rule that makes you share a man!

You slave like maids but without pay.

Michael R. Burch

LINKS

Life and Poetry

John Balaban on the work of Ho Xuan Huong

Wikipedia page on Ho Xuan Huong

Pat Valdata on the work of Ho Xuan Huong

Van Hoa Pham on femininity in the poetry of Ho Xuan Huong

“Me So Horny”: Linh Dinh on translations of Ho Xuan Huong

A brief biography and photo gallery on the My Poetic Side site

Poems

49 poems in the original language with translations by John Balaban

16 poems on the All Poetry site

14 poems on the My Poetic site

12 poems on the Hypertexts site translated by Michael R. Burch

5 poems on Poetry Foundation translated by Marylin Chin

2 poems translated by Natalie Linh Bolderston

2 poems translated by Mỹ Ngọc Tô

The Copper Canyon Press page on Spring Essence: The Poetry of Hô Xuân Huong

of Hồ Xuân Hương

by Đặng Quý Khoa.

Edward Storer (1880–1944) was an English writer, translator, and poet who was born in Alnwick, a market town in Northumberland, on 25 July 1880 to Frances Anne Egan and James John Robson Storer. Initially he studied law and qualified as a solicitor. In 1907 he was on the Roll of the Law Society of England and Wales. However, he practised law only for two years as his main interest in poetry soon dominated his time.

Edward Storer (1880–1944) was an English writer, translator, and poet who was born in Alnwick, a market town in Northumberland, on 25 July 1880 to Frances Anne Egan and James John Robson Storer. Initially he studied law and qualified as a solicitor. In 1907 he was on the Roll of the Law Society of England and Wales. However, he practised law only for two years as his main interest in poetry soon dominated his time.

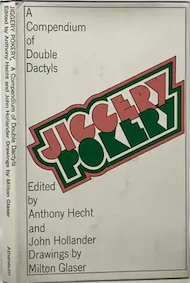

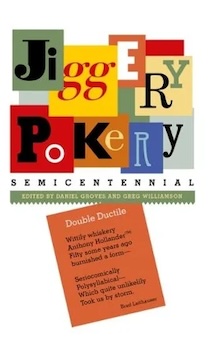

Fifty years after Atheneum published Jiggery-Pokery, Waywiser published Jiggery-Pokery Semicentennial (2018), a new compendium edited by Dan Groves and Greg Williamson. Dedicated to the memories of Hecht and Hollander, and with an introduction by Willard Spiegelman, it comes complete with a cover by the celebrated graphic designer Milton Glaser who designed the cover for and also illustrated the original Hecht-Hollander volume.

Fifty years after Atheneum published Jiggery-Pokery, Waywiser published Jiggery-Pokery Semicentennial (2018), a new compendium edited by Dan Groves and Greg Williamson. Dedicated to the memories of Hecht and Hollander, and with an introduction by Willard Spiegelman, it comes complete with a cover by the celebrated graphic designer Milton Glaser who designed the cover for and also illustrated the original Hecht-Hollander volume.