I’m a big believer in the notion that taxes change behavior. I even have a five-part series (here, here, here, here, and here) emphasizing the point.

emphasizing the point.

The core insight is that people respond to incentives.

But I also think there is a limit to how much taxes change behavior.

To give an example, the Straits Times in Singapore has a story about a very weird development in China.

The government is imposing a tax on birth control in hopes of boosting birth rates. I’m not joking. Here are some excerpts.

China will impose a value-added tax on contraceptive drugs and devices – including condoms – for the first time in three decades, its latest bid to reverse plunging birth rates that threaten to further slow its economy. Under the newly revised Value-Added Tax (VAT) Law, consumers will pay a 13 per cent levy on items that had been VAT-exempt since 1993, when China enforced a strict one-child policy and actively promoted birth control.

…The country has also announced guidelines to reduce the number of abortions that are not deemed “medically necessary” – in sharp contrast to the coercive reproductive controls of the one-child era, when abortions and sterilisations were routinely enforced. …The extra cost quickly sparked debate on Chinese microblogging site Weibo, with some users worrying not just about the potential for unplanned pregnancy, but also whether sexually transmitted diseases could spread more quickly if people were using fewer condoms. …Others mocked the tax as ineffective – arguing that higher prices would do little to change attitudes toward childbearing. “If someone can’t afford a condom, how could they afford raising a child?” one person asked.

For what it’s worth, I don’t think the Chinese tax-birth-control approach will work any better than the Hungarian subsidize-babies approach.

Restrictions on abortion presumably would have a bigger impact, though obviously this would be very controversial.

My two cents is that birthrates are probably not very sensitive to changes in government policy. So demographic decline may be irreversible (in China and elsewhere).

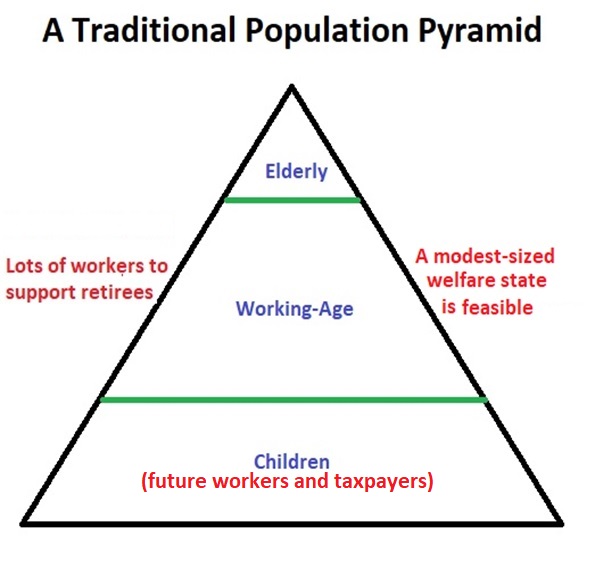

In other words, say goodbye to the population pyramids that are necessary for programs like Social Security.

The obvious conclusion is that it is very important for nations to shift away from tax-and-transfer entitlement programs that are predicated on lots of households having lots of children.

P.S. If you want to be depressed, peruse my five-part series on demographic change and fiscal crisis (here, here, here, here, and here).