I have a five-part series (here, here, here, here, and here) explaining that demographic decline will lead to fiscal crisis.

The main takeaway is that entitlement programs are a ticking time bomb, and I castigate politicians who want to kick the can down the road (or make a bad situation even worse).

This is a global problem, not merely an American problem, as illustrated by this chart published in June by the Washington Post.

Today, let’s contemplate how to solve this looming crisis.

The good news is that some politicians are finally realizing that changes are needed.

In a report for the Washington Post, Chico Harlan documents how a few governments are trying to address the problem. Here are some excerpts.

After years of people having fewer children, Europe is on the brink of a great contraction. …That trajectory has raised alarms about shrinking workforces and the possibility of economic insolvency. So governments of every political stripe are scrambling to test whether some mix of perks, incentives and ideology might spark a baby boom.

…governments are rolling out generous financial incentives for potential parents — while also extolling traditional families. …But the lesson so far from Europe is that even enormous government programs might yield just fractional change. …Until the 1960s, most of Europe maintained fertility rates above 2.1 births per woman, the level needed to sustain a population. …But now, …5 of 27 E.U. countries have birth rates above 1.5, and none is above 1.9. The E.U. fertility rate stands at a record low 1.38 births per woman. …Thirty years ago, across Western Europe, there were four adults younger than 65 for every one senior. Now the ratio is about 3 to 1. By 2050, it’ll be less than 2 to 1. And by 2100, according to United Nations projections, Western Europe will have more people age 85 than 5.

In other words, Europe is demographically dying.

And that means a fiscal crisis, probably sooner rather than later.

But can that fate be avoided by convincing families to have more children?

The article points out that this approach has not been successful, even in Hungary where the government has a very aggressive policy to increase birth rates.

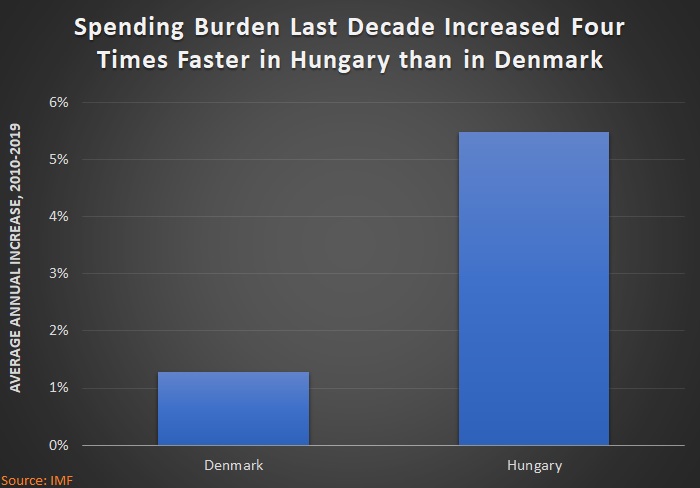

…No country better embodies the ambitions and limits than Hungary… The country now spends 5 percent of its gross domestic product on family policies… For a while, Hungary’s policies looked like a clear triumph. Orban started introducing incentives about 15 years ago, just after Hungary’s population had fallen below 10 million for the first time in decades. Its fertility rate, 1.25, stood among the lowest in Europe. Over the following decade, global fertility plummeted even faster than demographers had anticipated. But Hungary defied the trend: By 2015, its fertility rate had climbed to 1.45. By 2021, 1.61. Then, the direction reversed — all the way down to 1.39 by 2024, almost exactly the E.U. average.

Here’s a look at fertility (left axis) and births (right axis) in Hungary.

Tim Carney, in a column for the Washington Examiner, takes a close look at Hungary’s birth dearth.

In Budapest eight months ago, I heard many hopeful Hungarian conservatives point out that Hungary had risen from the bottom of European birth rates to almost the top. They credited the administration of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, who had implemented all sorts of pro-family policies, including lots of cash, accommodations, and tax breaks for parents.

But…there were reasons to worry whether Hungary really was resisting the global collapse in birth rates. In 2024, its birth rate had fallen and was closer to the middle of the European pack than the top. The 2025 numbers so far are dreadful. Hungary’s total fertility rate is down to 1.30 babies per woman, way down from 1.51 in 2023, which itself is far lower than the United States. Compare Hungary to its neighbors — Slovakia, Slovenia, Austria, Croatia, Serbia, and Romania. Among those countries, Hungary is tied for the lowest birth rate with Austria. …Hungary’s 10-year fertility drop, which includes many years of family policy, is 10%, worse than five of its six neighbors.

Tim explains in the column that maybe the subsidies simply caused families to have kids earlier, but not to have more kids.

That hypothesis seems plausible, and a 2023 story in the New York Times also shows that government efforts to boost birth rates have only temporary effects.

As in Sweden.

And Australia.

The bottom line, as I explained in 2017, is that governments lack to ability to substantially increase birth rates.

P.S. China is trying to boost birth rates by taxing birth control, and some crazy leftists want government-run dating apps. Good luck with those ideas.

P.P.S. You may have noticed, in the first chart above, that China’s birth rate jumped in the mid-1960s. That presumably is a statistical blip because Mao’s horrific policies led to catastrophic starvation and suffering in the early 1960s.