I certainly don’t intend to do this for everyone who has made it to the White House, but I have produced big-picture economic assessments of several presidents.

Today, let’s go back farther in history and take a look at Woodrow Wilson.

At the risk of understatement, he did a very bad job. Indeed, it’s quite likely that he ranks as America’s worst president, at least when judging economic policy. His mistakes were either huge or disgusting.

Creating the income tax – The internal revenue code began when Wilson signed into law an income tax on October 3, 1913. The initial tax wasn’t overly onerous – with a top rate of just 7 percent – but it predictably evolved into the punitive levy that currently plagues America.

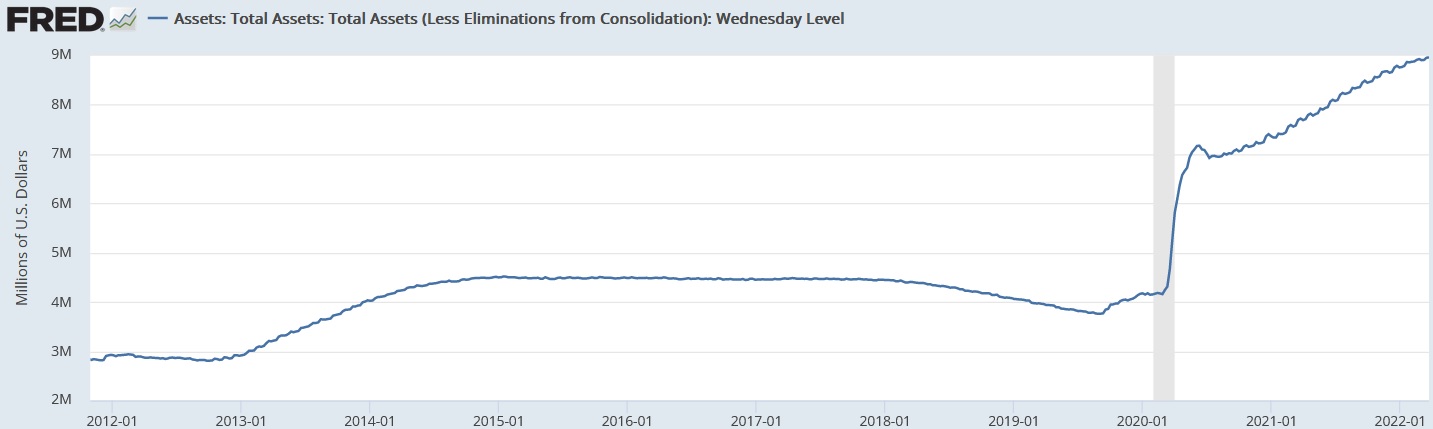

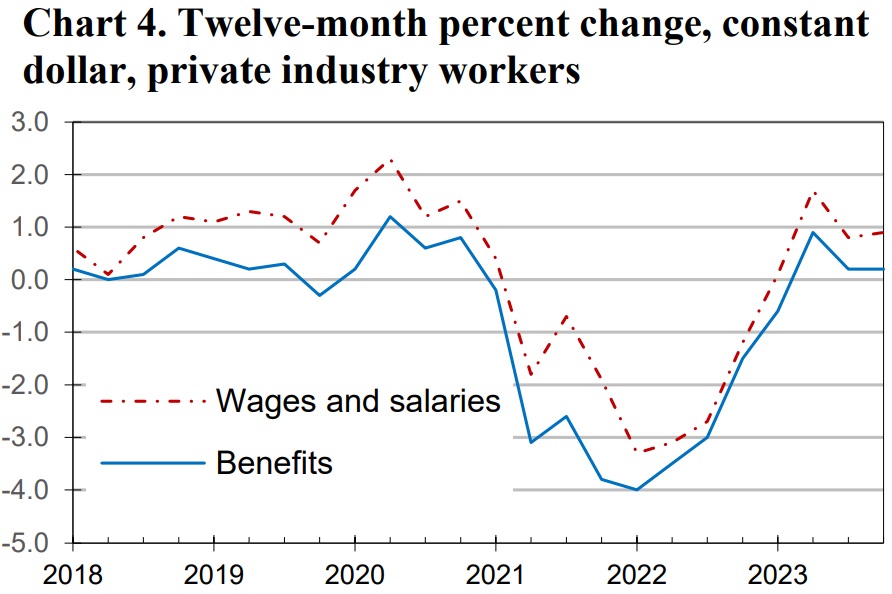

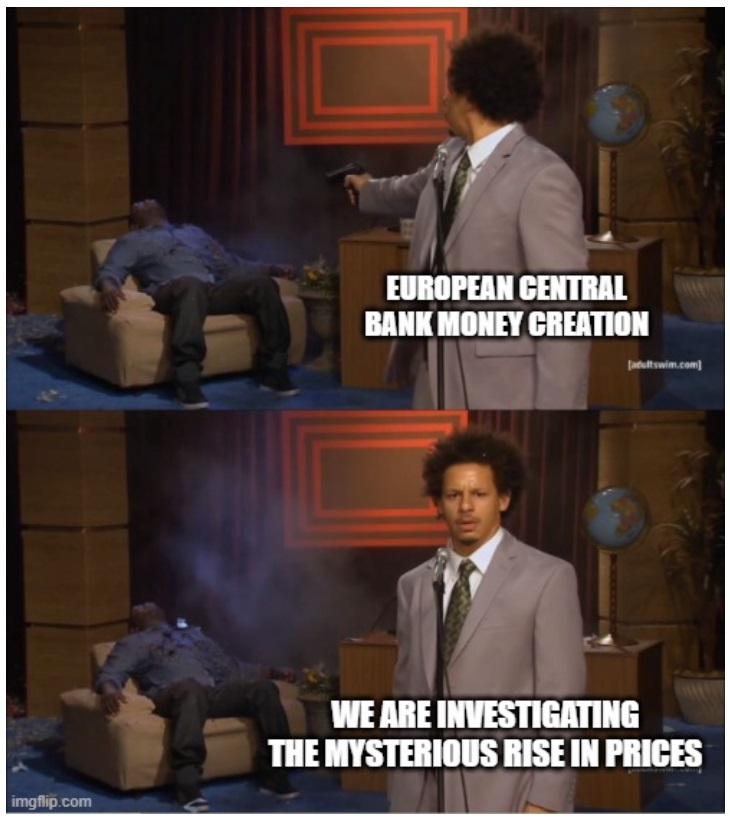

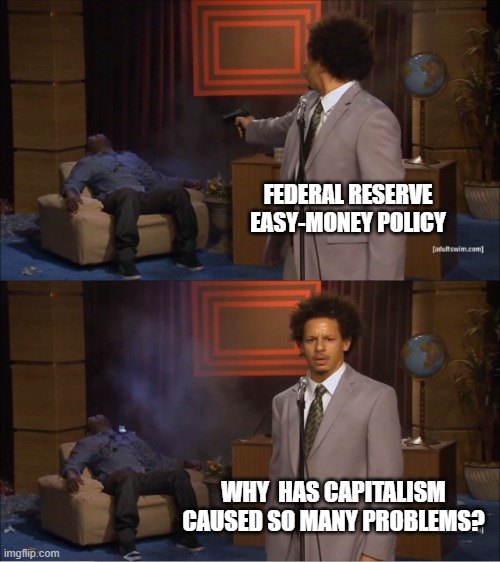

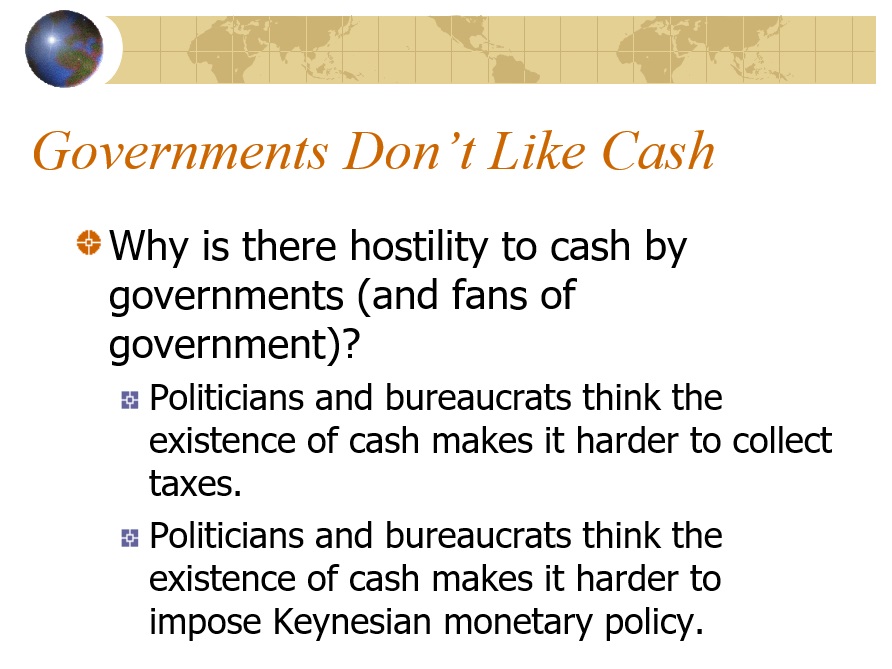

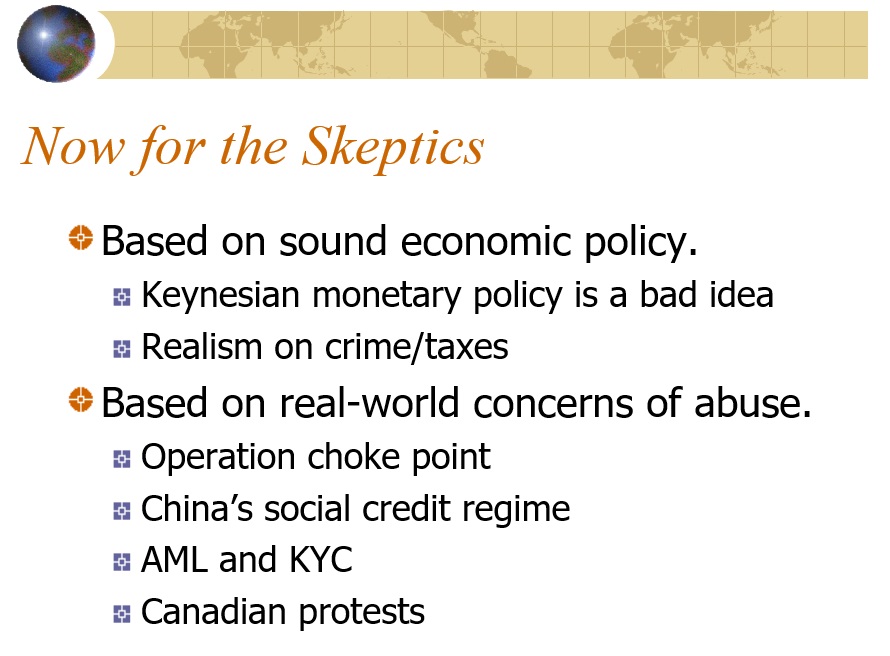

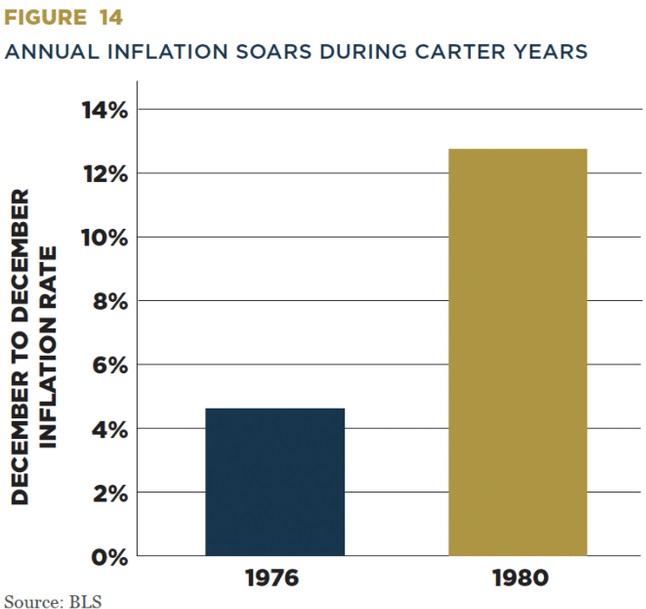

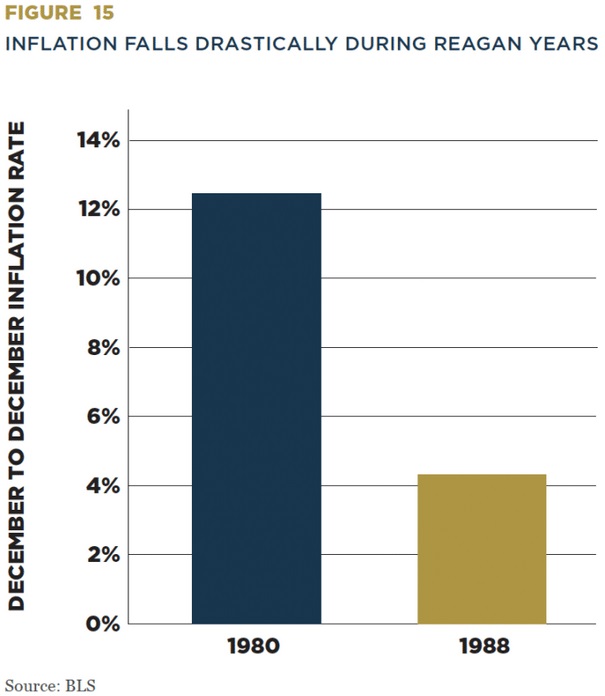

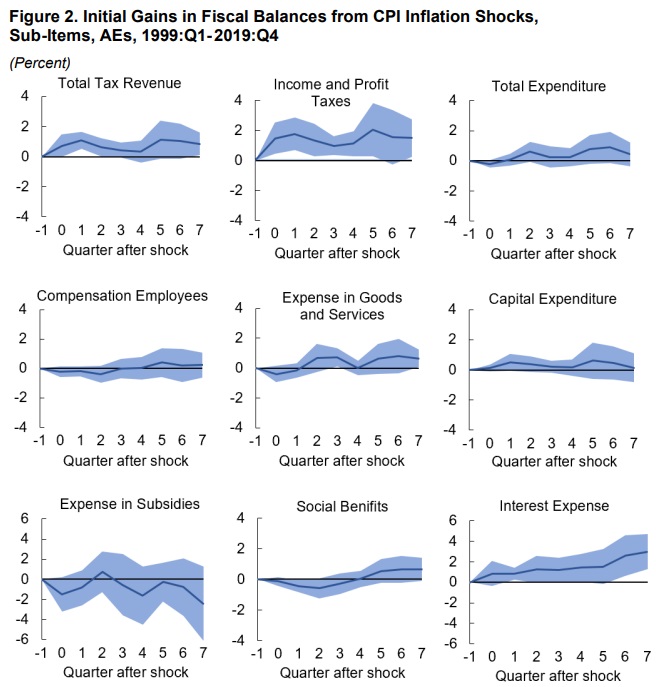

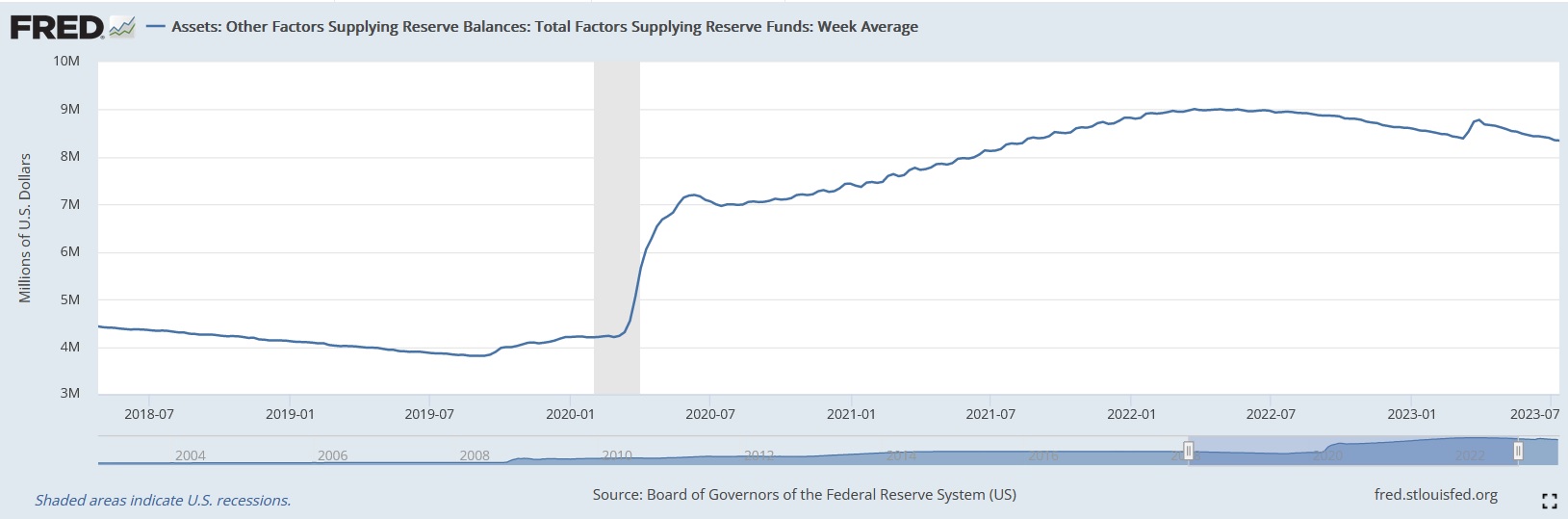

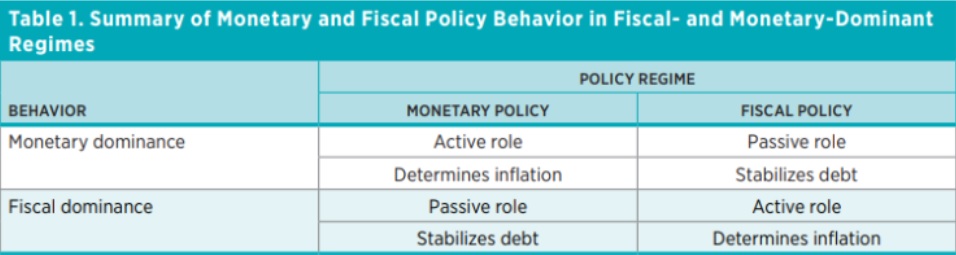

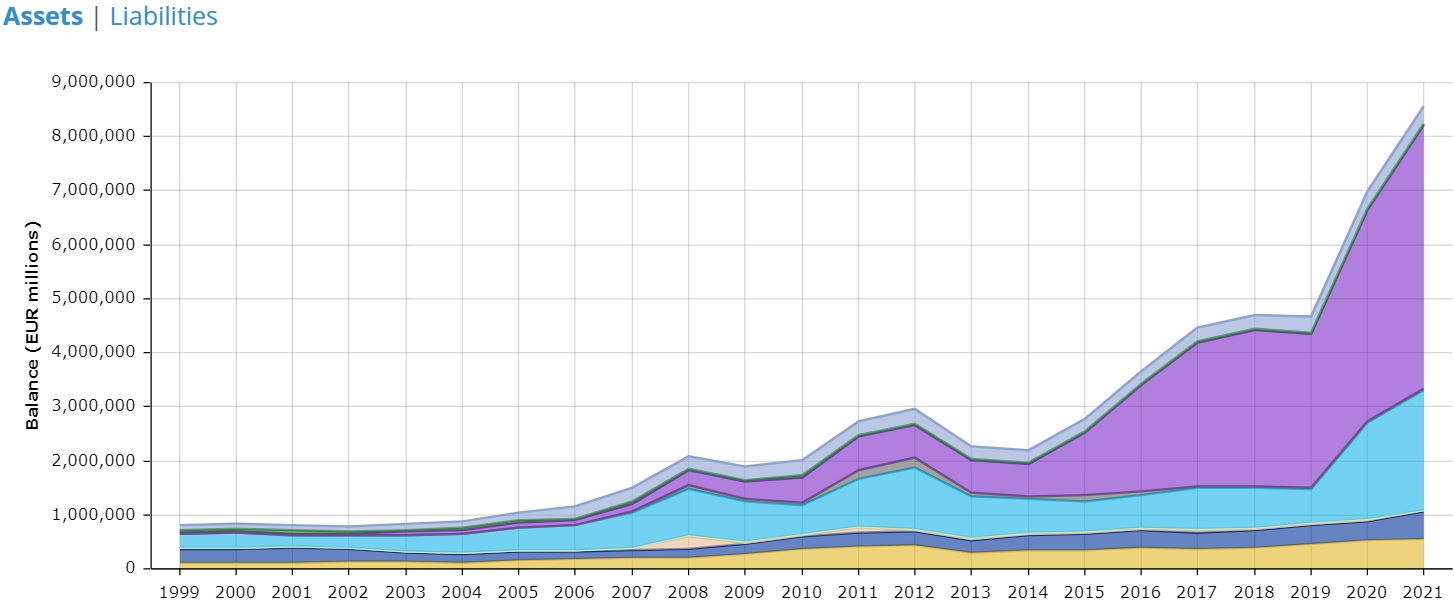

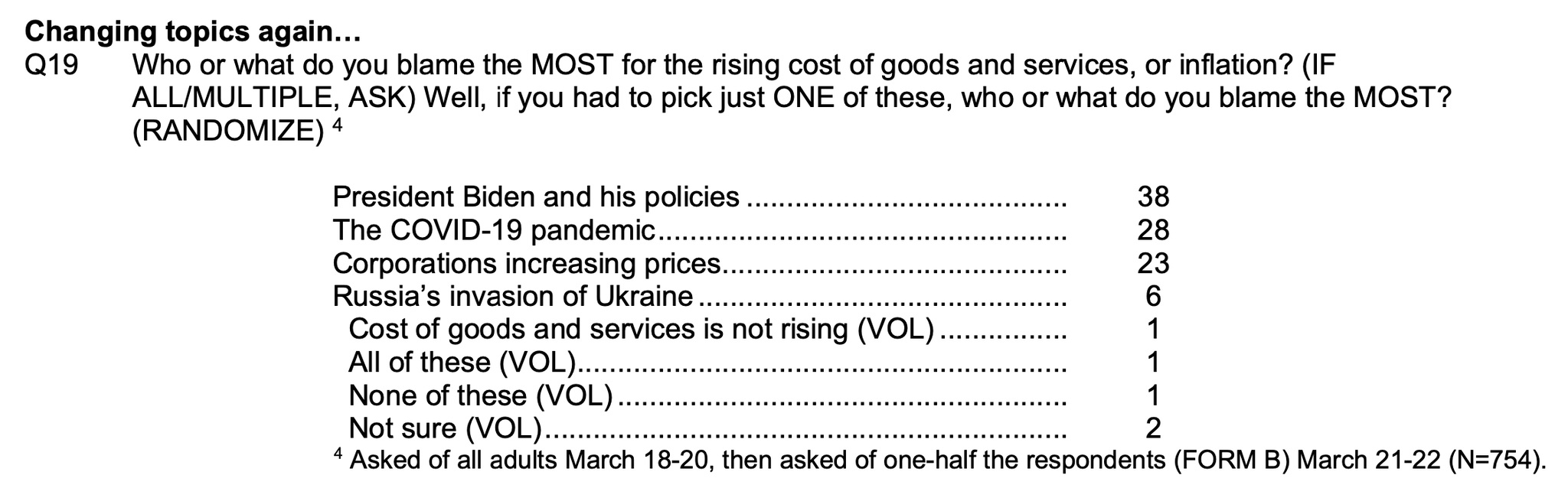

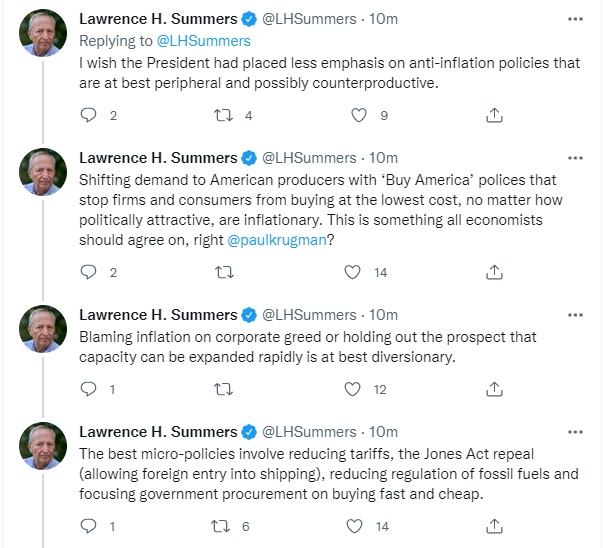

Creating the Federal Reserve – You don’t have to be a libertarian-minded advocate of competitive currencies to conclude that the central bank – also signed into law by Wilson in 1913 – has caused immense damage with its erratic, boom-bust approach to monetary policy.

Creating the Federal Reserve – You don’t have to be a libertarian-minded advocate of competitive currencies to conclude that the central bank – also signed into law by Wilson in 1913 – has caused immense damage with its erratic, boom-bust approach to monetary policy.

Segregating the federal government – Wilson was a reprehensible racist. To make matters worse, he turned that personal moral failing into a big policy mistake by overseeing rampant (and costly) discrimination and segregation in the federal government.

Those are just the highlights – though lowlights would be a more accurate word to describe Wilson’s policies.

The Encyclopedia Britannica has a description of some additional forms of intervention imposed during his tenure.

…he took up and pushed through Congress the Progressive-sponsored Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914. It established an agency—the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)—with sweeping authority. …because his own political thinking had been moving toward a more advanced Progressive position—Wilson struck out upon a new political course in 1916. He began by appointing Louis D. Brandeis, the leading critic of big business and finance, to the Supreme Court. Then in quick succession he obtained passage of a rural-credits measure to supply cheap long-term credit to farmers; anti-child-labour and federal workmen’s-compensation legislation; the Adamson Act, establishing the eight-hour day for interstate railroad workers; and measures for federal aid to education and highway construction.

He began by appointing Louis D. Brandeis, the leading critic of big business and finance, to the Supreme Court. Then in quick succession he obtained passage of a rural-credits measure to supply cheap long-term credit to farmers; anti-child-labour and federal workmen’s-compensation legislation; the Adamson Act, establishing the eight-hour day for interstate railroad workers; and measures for federal aid to education and highway construction.

Lawrence Reed of the Foundation for Economic Education put together a damning indictment of Wilson.

1913…was a disastrous year that we’re still paying a hefty, annual price for… Wilson, arguably the worst president…ordered the segregation of all departments within the executive branch and appointed ardent segregationists to high positions. …He locked up political dissidents right and left as he trampled on the Constitution’s guarantees of speech, assembly, and press freedoms. His wartime economic controls were hideously stupid and counterproductive. …the 16th Amendment to the Constitution was…Strongly supported by Wilson… Subsequent legislation set the top rate at a mere 7 percent. …When Wilson left office eight years later, the top rate was more than ten times higher. …Wilson’s signature enshrined into law the Federal Reserve Act, creating a central bank and more economic mischief than any other federal initiative or institution in the last 100 years. …In American history, 1913 should go down as a year that will live in infamy.

His wartime economic controls were hideously stupid and counterproductive. …the 16th Amendment to the Constitution was…Strongly supported by Wilson… Subsequent legislation set the top rate at a mere 7 percent. …When Wilson left office eight years later, the top rate was more than ten times higher. …Wilson’s signature enshrined into law the Federal Reserve Act, creating a central bank and more economic mischief than any other federal initiative or institution in the last 100 years. …In American history, 1913 should go down as a year that will live in infamy.

It’s also worth noting that Wilson was a believer in global governance, which adds to his awful legacy.

In a review of a biography about Wilson for the Claremont Review of Books, David Goldman mentions that unpalatable feature of his presidency.

So utterly utopian was Wilson’s vision that it is unfair to characterize the internationalism of Bill Clinton or George W. Bush as “Wilsonian.” Clinton and Bush threw America’s weight around after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but they did not propose—as Wilson did—to replace America’s sovereign decision-making with a global council. …He wanted to compromise American sovereignty and most of the Senate did not. …Wilson would have liked to impose a legal obligation from a foreign body upon the United States, but could not say so openly. …His obsession was the creation of a supranational agency able to dictate policy to national governments, an obsession that grew out of his lifelong hostility to the American political system… To make sense of his grand overreach in 1919, historians will need to give more attention to his rancor at the U.S. Constitution… The constitution in Wilson’s reading had become a relic of a bygone era. He proposed to jettison this putatively archaic document in favor of a government less burdened by checks and balances. …The same utilitarian criteria that Wilson applied to the Constitution guided his judgment about capitalism and socialism. …As economists Clifford Thies and Gary Pecquet have observed, “Wilson believed that the difference between socialism and democracy was a matter of means rather than ends.” …He eschewed mass expropriation of industry only because he thought it inefficient. …Although Wilson’s dudgeon came from the Deep South, his Progressivism came from Princeton and the Social Gospel.

…Wilson would have liked to impose a legal obligation from a foreign body upon the United States, but could not say so openly. …His obsession was the creation of a supranational agency able to dictate policy to national governments, an obsession that grew out of his lifelong hostility to the American political system… To make sense of his grand overreach in 1919, historians will need to give more attention to his rancor at the U.S. Constitution… The constitution in Wilson’s reading had become a relic of a bygone era. He proposed to jettison this putatively archaic document in favor of a government less burdened by checks and balances. …The same utilitarian criteria that Wilson applied to the Constitution guided his judgment about capitalism and socialism. …As economists Clifford Thies and Gary Pecquet have observed, “Wilson believed that the difference between socialism and democracy was a matter of means rather than ends.” …He eschewed mass expropriation of industry only because he thought it inefficient. …Although Wilson’s dudgeon came from the Deep South, his Progressivism came from Princeton and the Social Gospel.

Wilson’s hostility to the Constitution was part of the so-called progressive era. Unlike America’s Founders, proponents of this approach viewed the federal government as a positive force rather than something to be constrained.

The idea that government or “the community,” has “an absolute right to determine its own destiny and that of its members” is a progressive one. The difference between the Founders’ and progressive’s visions can be summarized this way: The Founders believed citizens could best pursue happiness if government was limited to protecting the life, liberty, and property of individuals. …Unlike the framers of the Constitution, progressives believed that…“communities” have rights, those rights are more important than the personal liberty of any one individual in that community. …they believed…government-sponsored programs and policies as well as economic redistribution of goods from the rich to the poor. …Wilson, who served as president from 1913-1919, advocated what we today call the living Constitution, or the idea that its interpretation should adapt to the times. …Wilson oversaw the implementation of progressive policies such as the introduction of the income tax and the creation of the Federal Reserve System to attempt to manage the economy.

…Unlike the framers of the Constitution, progressives believed that…“communities” have rights, those rights are more important than the personal liberty of any one individual in that community. …they believed…government-sponsored programs and policies as well as economic redistribution of goods from the rich to the poor. …Wilson, who served as president from 1913-1919, advocated what we today call the living Constitution, or the idea that its interpretation should adapt to the times. …Wilson oversaw the implementation of progressive policies such as the introduction of the income tax and the creation of the Federal Reserve System to attempt to manage the economy.

Bre Payton, in an article for the Federalist, opined about Wilson and the changes during the progressive era.

…to understand The New Deal and how American life and government changed in the twentieth century and beyond, it is vital to understand the Progressive Era…  FDR cited progressive-minded presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson as his intellectual inspirations. …Progressives believed restricting government to only protecting citizens’ life, liberty, and ability to pursue happiness was simplistic. …Thus people should not fear the ever-expanding role of government… Wilson went on to say that modern European thinkers had declared that men were defined not by their individuality, but by their society. And one’s rights come from government.

FDR cited progressive-minded presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson as his intellectual inspirations. …Progressives believed restricting government to only protecting citizens’ life, liberty, and ability to pursue happiness was simplistic. …Thus people should not fear the ever-expanding role of government… Wilson went on to say that modern European thinkers had declared that men were defined not by their individuality, but by their society. And one’s rights come from government.

Hostility to the Constitution and limited government was just one problem with the progressives.

Their views of minorities also were very troubling.

In a column for National Review, Paul Rahe documented not only Wilson’s racism, but also his use of government power to harm the economic prospects for black Americans.

Wilson, our first professorial president, was…the very model of a modern Progressive…he shared the conviction, dominant among his brethren, that African-Americans were racially inferior to whites. …Prior to the segregation of the civil service in 1913, appointments had been made solely on merit as indicated by the candidate’s performance on the civil-service examination. Thereafter, racial discrimination became the norm. …The existing work force was segregated. Many African-Americans were dismissed. …Jim Crow had not been the norm before 1890, even in the deep South. …it became the norm there only when it received sanction from the racist Progressives in the North. …For similar reasons, Wilson was hostile to the constitutional provisions intended as a guarantee of limited government. The separation of powers, the balances and checks, and the distribution of authority between nation and state distinguishing the American constitution he regarded as an obstacle.

Thereafter, racial discrimination became the norm. …The existing work force was segregated. Many African-Americans were dismissed. …Jim Crow had not been the norm before 1890, even in the deep South. …it became the norm there only when it received sanction from the racist Progressives in the North. …For similar reasons, Wilson was hostile to the constitutional provisions intended as a guarantee of limited government. The separation of powers, the balances and checks, and the distribution of authority between nation and state distinguishing the American constitution he regarded as an obstacle.

This article from the New Republic covers the same ground, starting with his time as head of Princeton University, but from a left-wing perspective.

Wilson not only refused to admit any black students, he erased the earlier admissions of black students from the university’s history. …Elected president in 1912, …Wilson appeared to be the quintessential Progressive Era leader. …the progressive ideology of the era was in many ways quite racist. …it quickly became known that the Wilson administration was instituting a major modification in the treatment of black workers throughout the federal government from what had been the case under postwar presidents. …the Civil Service began demanding photographs to accompany employment applications for the first time. It was widely understood that the only purpose of this requirement was to weed out black applicants. …He insisted that the segregation policy was for the comfort and best interests of both blacks and whites.

…it quickly became known that the Wilson administration was instituting a major modification in the treatment of black workers throughout the federal government from what had been the case under postwar presidents. …the Civil Service began demanding photographs to accompany employment applications for the first time. It was widely understood that the only purpose of this requirement was to weed out black applicants. …He insisted that the segregation policy was for the comfort and best interests of both blacks and whites.

There’s more bad news about Wilson.

In a column for the Washington Post, Michael Beschloss, a presidential historian, writes about his authoritarianism as well as his racism.

His most disgraceful flaw was his racism. …Wilson especially stood out in his white supremacy. He was not a man of his time but a throwback. …Wilson, who preened as a civil libertarian, persuaded Congress to pass the Espionage Act, giving him extraordinary power to retaliate against Americans who opposed him and his wartime behavior. That same law today enables presidents to harass their political adversaries. Wilson’s Justice Department also convicted almost a thousand people for using “disloyal, profane, scurrilous or abusive language” against the government, the military or the flag. Wilson is an excellent example of how presidents can exploit wars to increase authoritarian power and restrict freedom.

giving him extraordinary power to retaliate against Americans who opposed him and his wartime behavior. That same law today enables presidents to harass their political adversaries. Wilson’s Justice Department also convicted almost a thousand people for using “disloyal, profane, scurrilous or abusive language” against the government, the military or the flag. Wilson is an excellent example of how presidents can exploit wars to increase authoritarian power and restrict freedom.

All things considered, definitely one of America’s worst chief executives.

This tweet is an apt summary of Wilson’s presidency.

For readers who are interested in the quirks of history, Lawrence Reed of the Foundation for Economic Education bemoans the fact that an untimely death in 1899 probably led to the unfortunate election of Wilson.

Garret Augustus Hobart—known to his friends as “Gus”—was America’s 24th vice president. He served under William McKinley for two years and eight months until his death in office in November 1899 at the age of 55. With Hobart’s untimely passing, President William McKinley had to find a new running mate for the election of 1900. That man turned out to be Theodore Roosevelt, who became president upon McKinley’s assassination only six months into his second term. …Teddy…enter the presidential race in 1912 as a third-party nominee. That split the Republican vote and handed the presidency to Democrat Woodrow Wilson. Wilson won with just 42% of the popular tally and went on to become arguably the very worst of our 45 chief executives. …I greatly lament the sad fact that Gus Hobart wasn’t around to run again with McKinley in 1900. If he had lived, he instead of Teddy would have become our 26th President when McKinley died. And if there had been no Teddy Roosevelt presidency, there might never have been a philandering, racist, “progressive” Wilson in the White House to royally screw up the country with an income tax, a Federal Reserve, entry into World War I, and other mischievous adventures in statism.

…Teddy…enter the presidential race in 1912 as a third-party nominee. That split the Republican vote and handed the presidency to Democrat Woodrow Wilson. Wilson won with just 42% of the popular tally and went on to become arguably the very worst of our 45 chief executives. …I greatly lament the sad fact that Gus Hobart wasn’t around to run again with McKinley in 1900. If he had lived, he instead of Teddy would have become our 26th President when McKinley died. And if there had been no Teddy Roosevelt presidency, there might never have been a philandering, racist, “progressive” Wilson in the White House to royally screw up the country with an income tax, a Federal Reserve, entry into World War I, and other mischievous adventures in statism.

In keeping with my traditional practice, here’s a visual depiction of the good and bad policies of the Wilson Administration.

And although it’s hard to measure, Wilson belongs in the presidential Hall of Shame because his administration was a turning point in America’s tragic evolution from Madisonian constitutionalism to modern statism.

For instance, Wilson almost surely paved the way for FDR’s ill-fated New Deal.

P.S. Now readers will hopefully understand why I wrote that Obama (who largely had a forgettable legacy) wasn’t nearly as bad at Wilson.

Read Full Post »