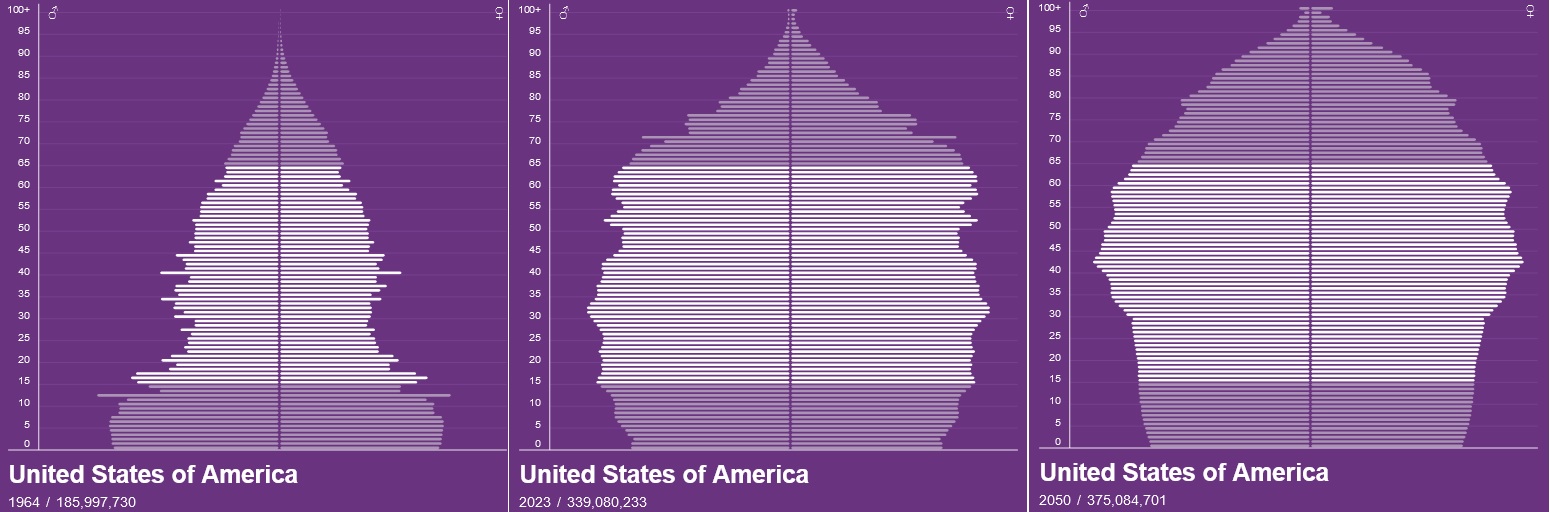

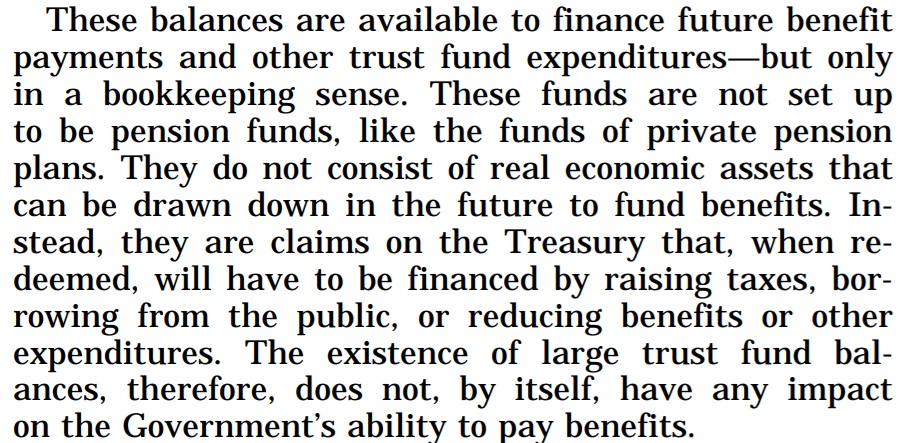

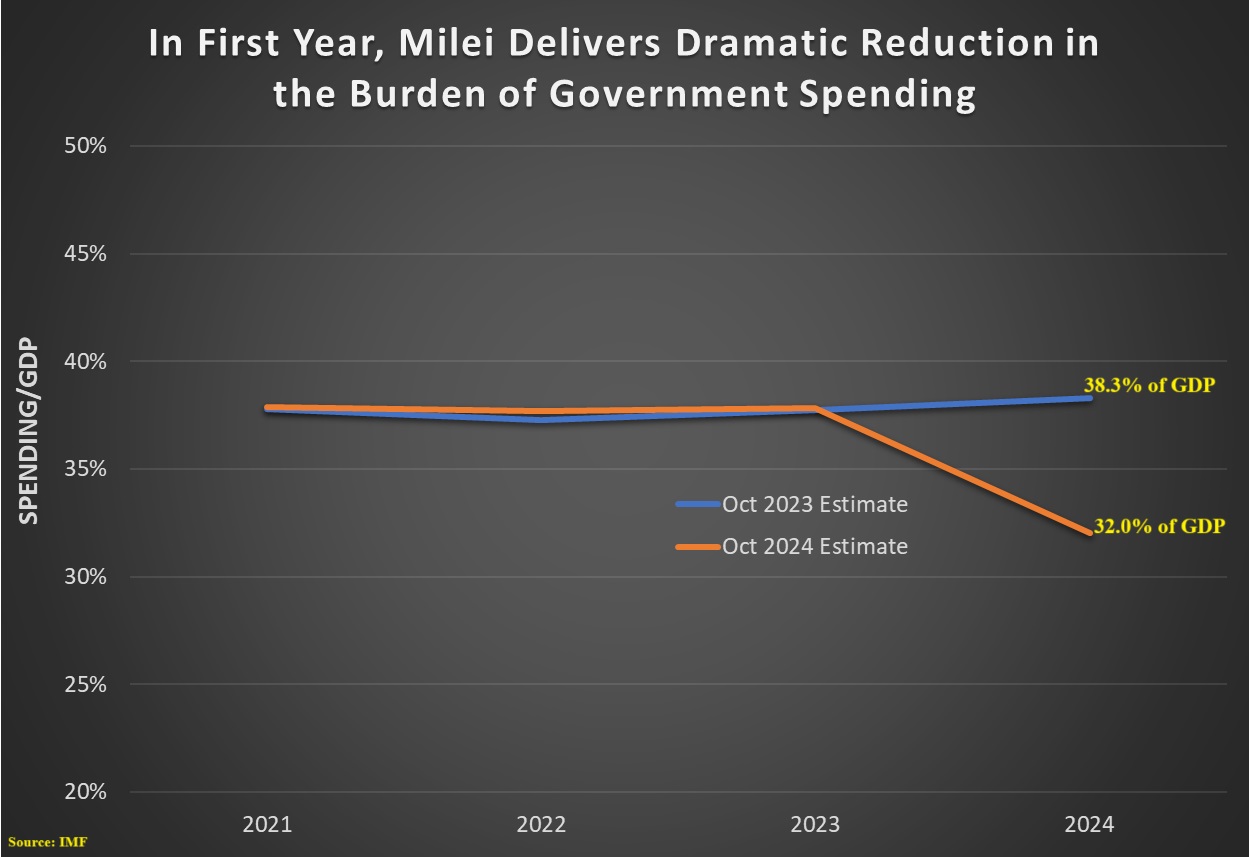

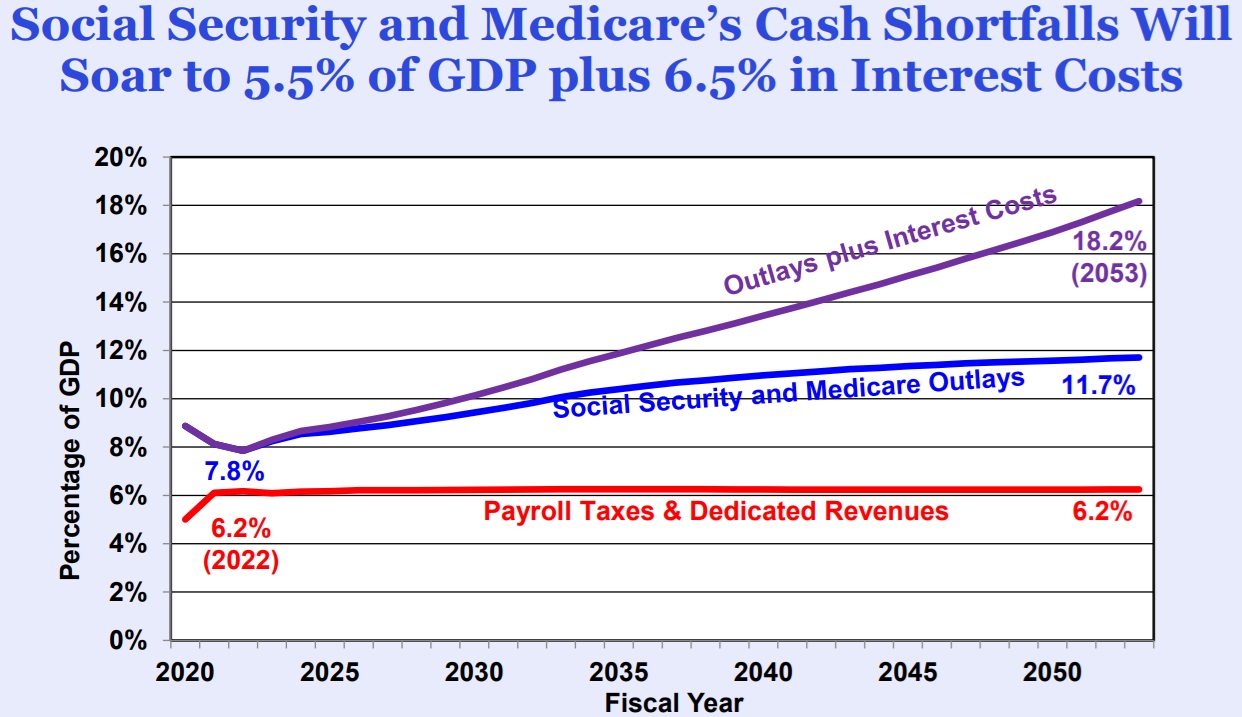

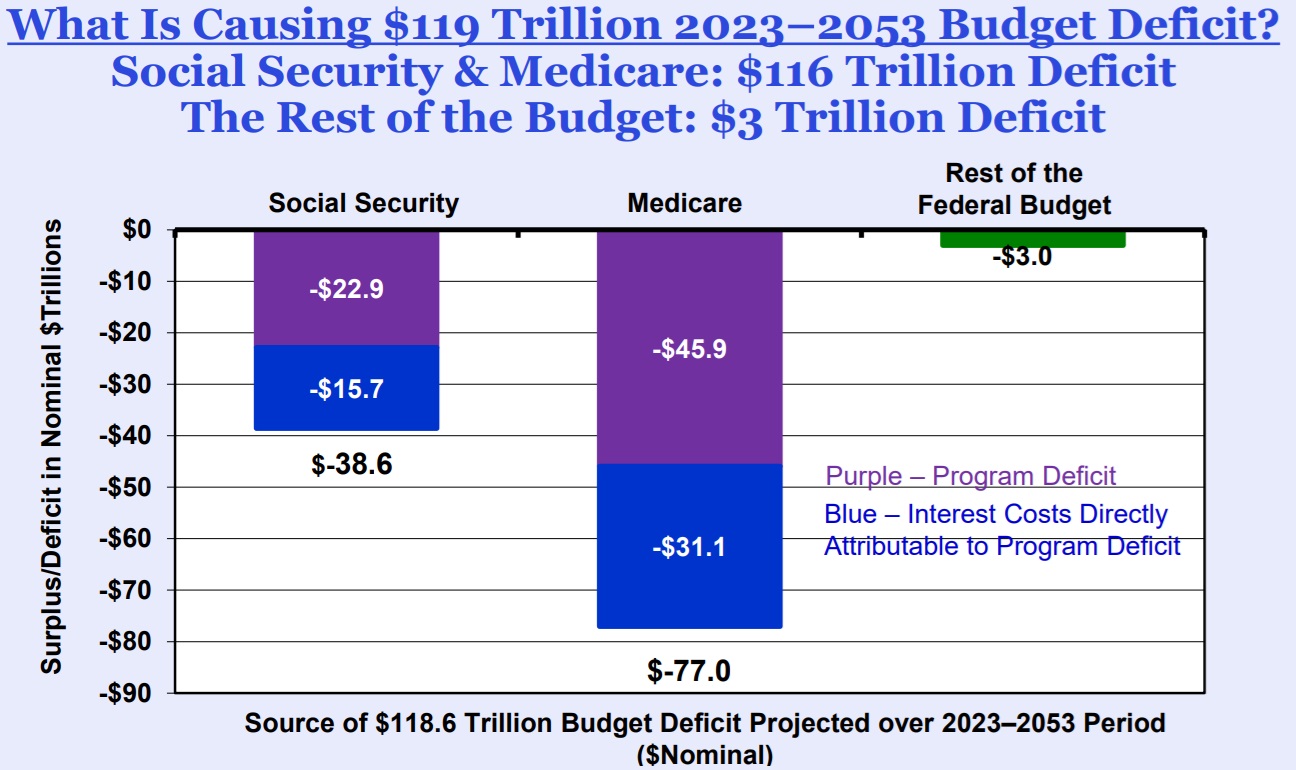

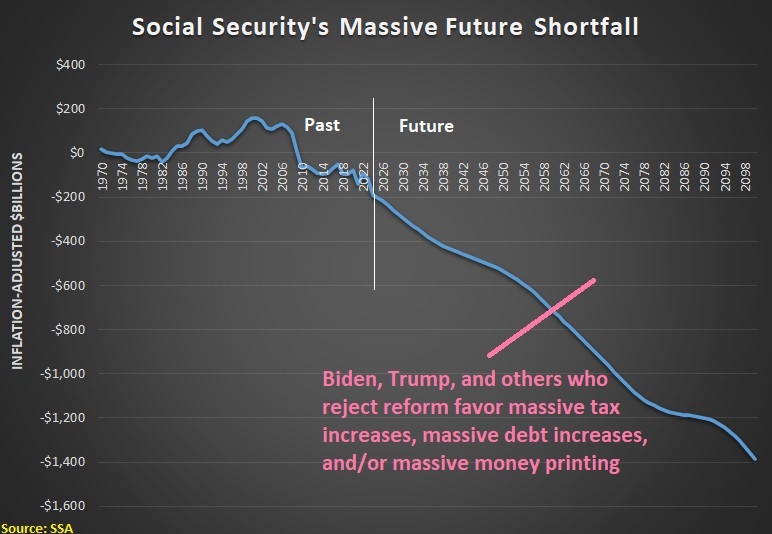

The United States faces a huge long-run fiscal problem because government is growing too fast.

Entitlement programs are the main problem.

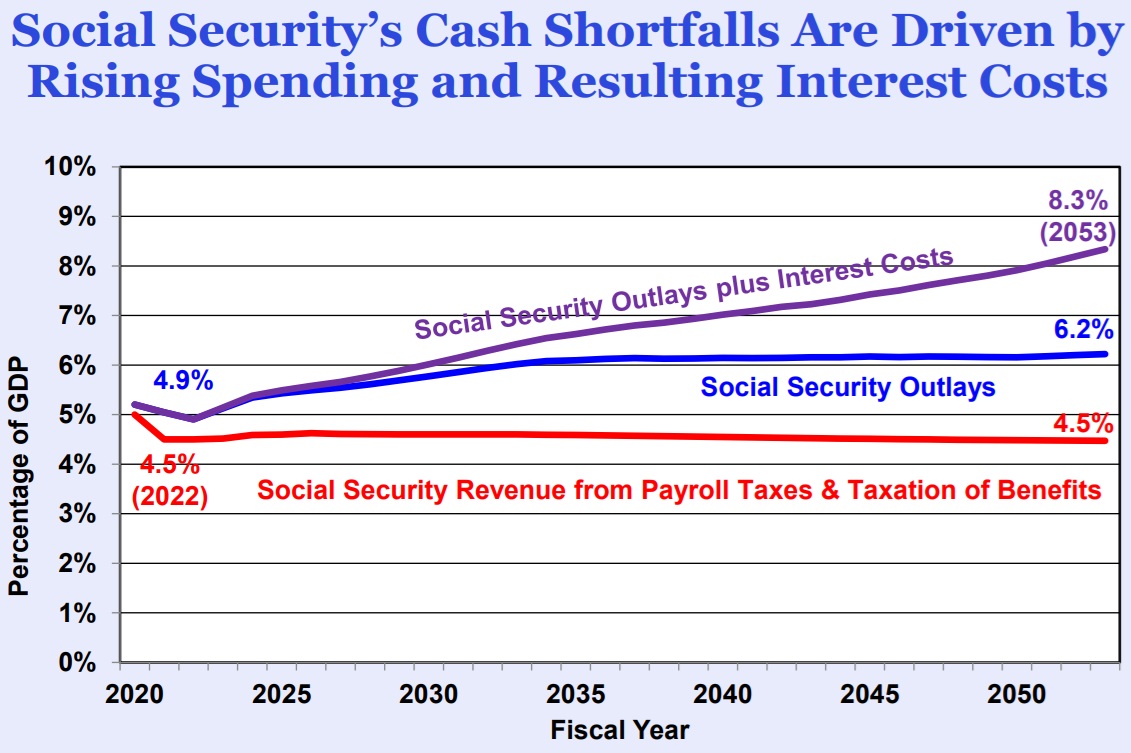

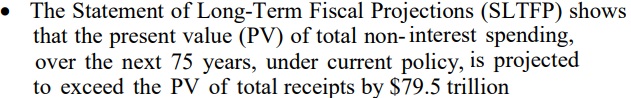

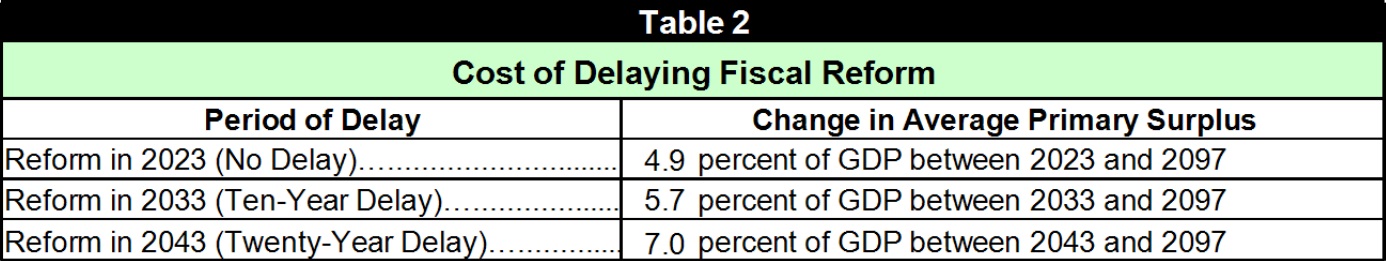

For example, a rising burden of Social Security spending means that outlays will exceed revenues by $65.8 trillion over the next 75 years.

Eventually, politicians will be forced to address this problem (hopefully before a crisis occurs!).

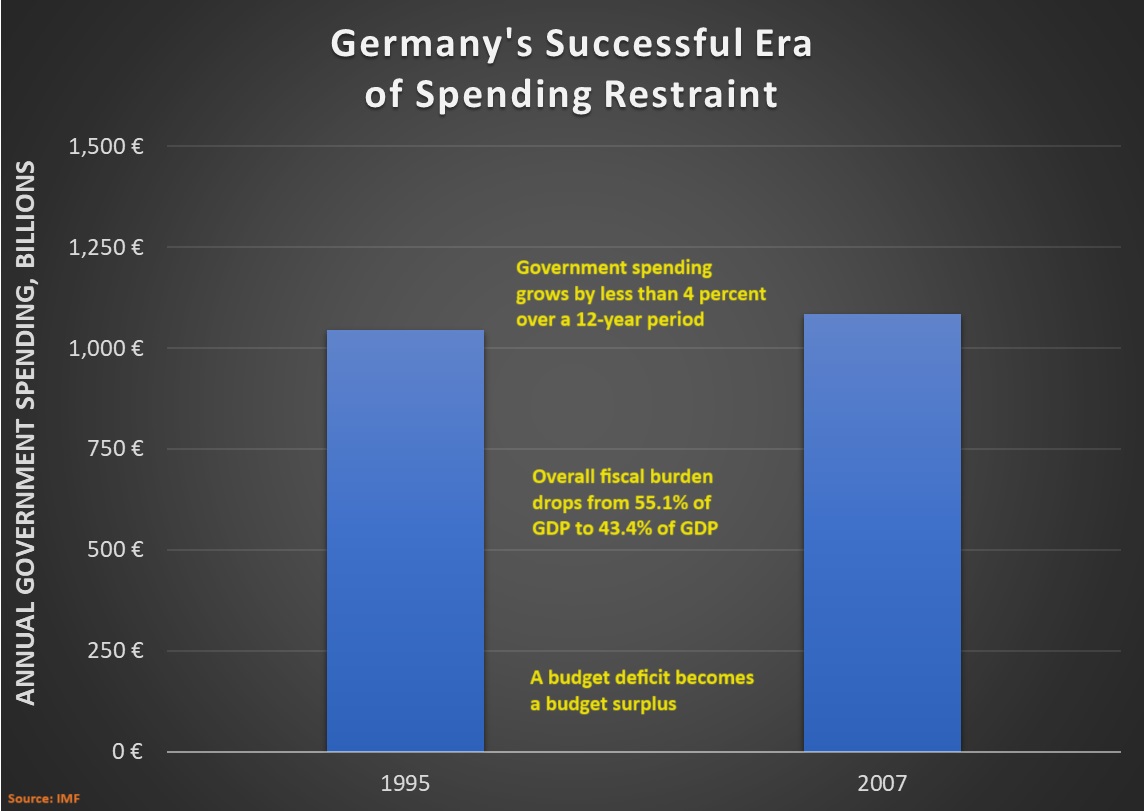

- But will they address the problem by slowing the growth of spending and complying with fiscal policy’s Golden Rule?

- Or will they seek to increase the trend line of revenue by taking more money from the productive sector of the economy?

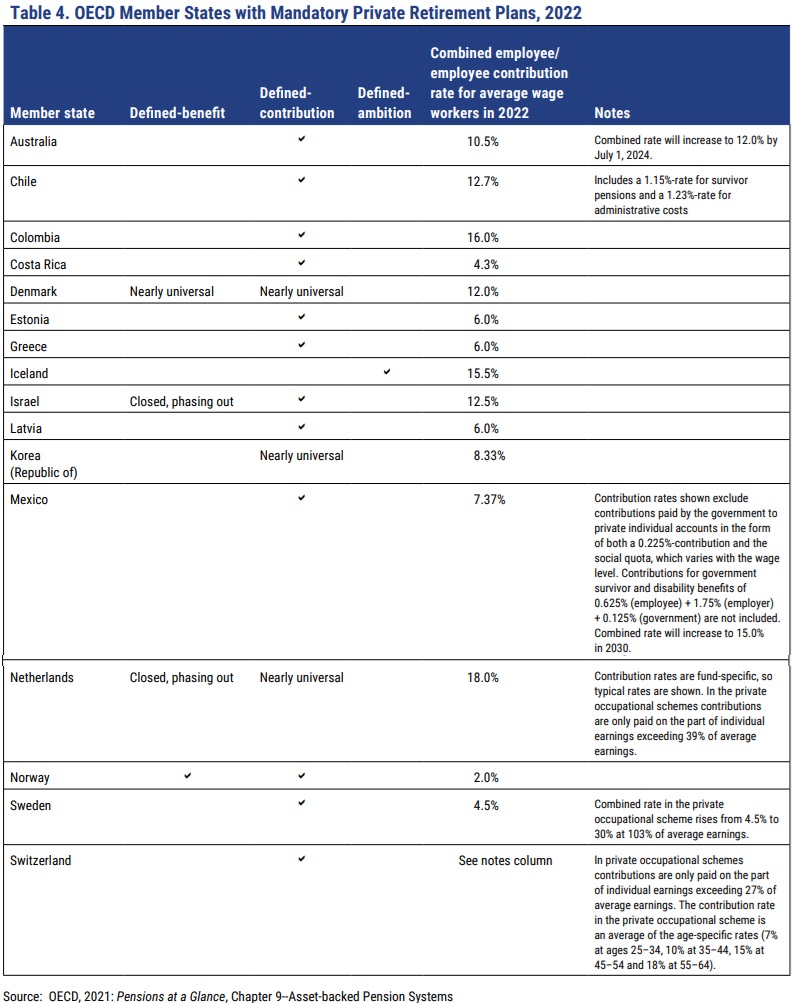

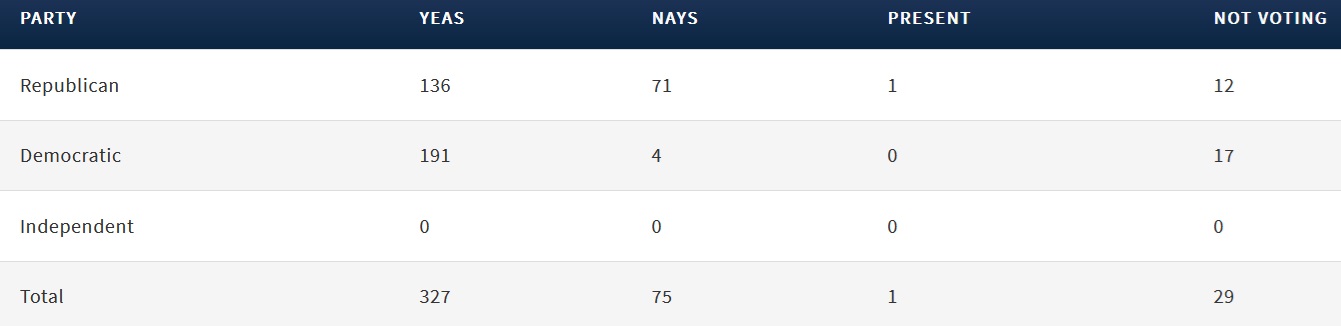

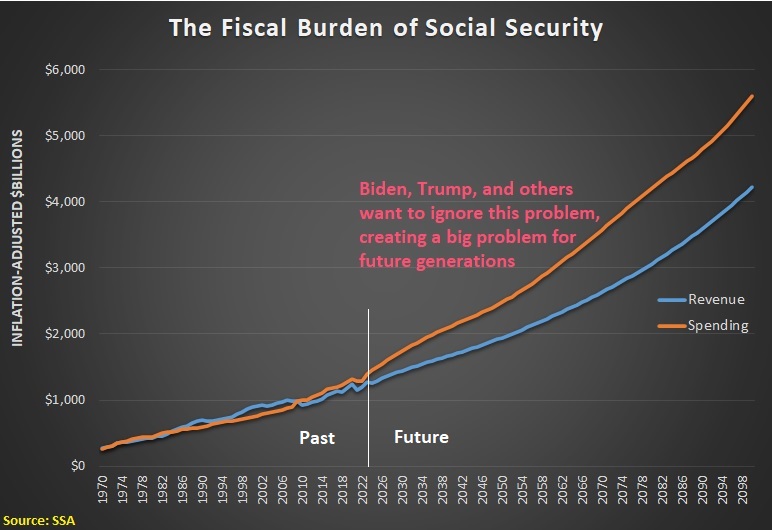

The bad news is that polls sometimes show support for higher taxes. Consider this new data from the Cato Institute, which shows (circled in red) that a majority of people support various tax increases to deal with Social Security’s massive shortfall.

But there’s also good news. Notice the fourth poll, the one showing that only a small minority of Americans would be willing to pay more than $1,300 per year.

Here’s some more data from the Cato poll. As you can see, there’s a huge drop in support for tax increases between $600 per year and $1,300 per year.

And why is this data significant?

Because, as the report explains, the average worker would have to pay about $2,600 per year to prop up the current system.

When asked what types of tax increases Americans would support in general terms, solid majorities say they would favor raising “income taxes” (58%) or “payroll taxes as much as necessary” (63%) to keep benefits intact. More specifically, a majority (55%) say they support raising payroll taxes from 12.4% to 16.05%. But framing tax increases in dollar amounts produces a very different response. Most Americans don’t think in terms of percentages.

When asked in concrete dollar amounts if they would be willing to raise their own taxes by $1,300 per year to maintain current benefits, an overwhelming majority (77%) say no. Yet, the realistic tax increase needed for the average worker is roughly $2,600 more per year, far above what the public is willing to pay. …These patterns hold across income levels. For instance, Americans earning more than $150,000 per year are about as unwilling as a person earning less than $30,000 per year to pay an additional $2,600 per year in payroll taxes (75% and 78%, respectively). Strong majorities of both Democrats (73%) and Republicans (86%) also oppose tax increases at the projected $2,600 level needed to maintain benefits.

I’ll close with two comments.

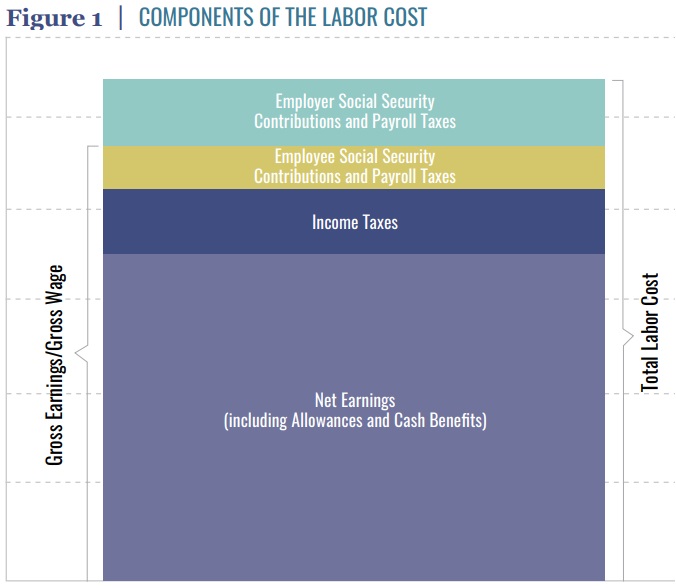

- First, our friends on the left will try to avoid opposition from middle-class voters by proposing to “tax the rich.” Their go-to option will be busting the wage-base cap for payroll taxes, but other class-warfare taxes would be on the table as well. A big problem with this approach, however, is that there are big Laffer-Curve effects when politicians try to raise taxes on people with substantial control over the timing, level, and composition of their income. As such, they’ll have to target the middle class at some point.

- Second, the aforementioned Cato research reminds me of the data I shared in 2016 showing that even left-wing voters were willing to pay only a tiny fraction of how much tax would be needed to finance Bernie Sanders’ plans for a bigger welfare state. And let’s not forget that there is also academic research showing that politicians avoid tax increases in election years.

Actually, I’ll add a third comment.

- The left has a political problem in that you can’t finance a big welfare state without taxing lower-income and middle-class taxpayers, but the right also has a problem in that big government Republicans like Trump are unwilling to deal with entitlements. And that inevitably will mean massive tax increases.

P.S. The 12th Theorem of Government and 13th Theorem of Government definitely apply to today’s analysis.