In yesterday's post, I began to describe in some detail the characteristics of the knowledge economy in the 21st century; in today's post I will continue to investigate some of the defining factors that identify the emergence of this economic paradigm.

Learning organizations and innovation systems

In a knowledge economy, organizations search for linkages to promote inter-organizational learning, and for outside partners and networks to provide complementary assets. These relationships help organizations

- spread the costs and risks associated with innovation

- gain access to new research results, acquire key technological components

- share assets in manufacturing, marketing and distribution.

As they develop new products and processes, organizations determine which activities they will undertake individually, in collaboration with other organizations, in collaboration with universities or research institutions, and with the support of government[1]. We can say that, as such, innovation is the result of numerous interactions between actors and institutions, which together form an "innovation system."

These innovation systems consist of the information flows and relationships which exist among industry, government and academic and other institutions in the development of science and technology. The interactions within these systems influences the innovative performance of organizations - and ultimately of the economy. The ‘knowledge distribution power’ of the system, or its capability to ensure timely access by innovators to relevant stocks of knowledge, is can be seen as a major determinant of economic growth.

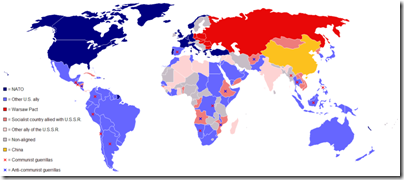

Strategy and location

One of the consequences of globalization combined with advances in communications technologies has been a strengthening of world competition, and the emergence of a new form of ‘global competition’. Most organizations in a dominant market position are, by necessity, multinational or transnational organizations. To compete successfully with their rivals, organizations must compete head-to-head in all markets (including their home market), and they must rapidly attain a global scale in production and/or rapidly roll out products and services into multiple markets in order to do so. In this environment, competitiveness depends increasingly on the coordination of, and alignment of a broad range of specialized industrial, financial, technological, commercial, administrative and cultural skills which can be located in many locations around the world[2].

Production is being rationalized globally, with organizations combining the factors, features and skills of various locations in the process of competing in global markets. There are three major dimensions of change involved:

- increasing national (locational) specialization

- increased international ‘fracturing’ of value chains or chains of production – witnessed in increased intra-industry and intra-firm trade

- greater line-item by line-item trade imbalances

An increasingly apparent consequence of this development in industrial ertia is substantial structural dislocation in local, regional and even national economies, and a consequent need for substantial structural adjustment.

Clustering in the Knowledge Economy

Networks and geographical clusters of firms are a particularly important feature of the knowledge economy. Organizations find it increasingly necessary to work with other firms and institutions in technology-based alliances, because of the rising cost, increasing complexity and widening scope of technology. Many organizations are becoming multi-technology corporations locating around centers of excellence in different countries. Despite improved capability for global communication, firms increasingly co-locate because it is the only effective way to share understanding[3]. Consequently, skills and life-style are becoming increasingly important locational factors.

As we enter the age of human capital, where organizations merely lease knowledge-assets, organizations’ location decisions are increasingly based upon quality-of-life factors that are important to attracting and retaining this economic asset. In high-tech services, strict business-cost measures are becoming less important to growing and sustaining technology clusters … Locations that are attractive to knowledge assets will play a vital role in determining the economic success of regions[4].

Economics of knowledge

In the knowledge economy there are new ground rules. Knowledge has fundamentally different characteristics from ordinary commodities and these differences have crucial implications for the way a knowledge economy must be organised[5]. The whole nature of economic activity, and our understanding of it, is changing.

Unlike physical goods information is non-rival – not destroyed in consumption. Its value in consumption can be enjoyed again and again. Hence, social return on investment in its generation can be multiplied through its diffusion. Ideas and information exhibit very different characteristics from the goods and services of the industrial economy. For example, much more than is the case with a frozen dinner or a haircut, the social value of ideas and information increases to the degree they can be shared with and used by others. More important, the costs associated with their production are distributed very differently over time. While up front costs associated with the production of traditional goods such as a car or house may not necessarily be high, each item is still costly to produce. The more of these one produces, the more likely one will eventually encounter scarcities that drive up production costs and reduce the size of social returns. In the case of innovation, ideas and information, however, the opposite would seem largely to be the case. While up front development costs can be very high, the reproduction and transmission costs are low. The more such items are (re)produced, the greater the social return on investment[6].

Traditional economics is founded on a system which seeks to optimise the efficient allocation of scarce resources, but because of the unique characteristics of information and knowledge the very meaning of scarcity is changing. Indeed, the scarcity defying expansiveness of knowledge is the root of one of its most important defining features. Once knowledge is discovered and made public, there is essentially zero marginal cost to adding more users[7].

More...

References:

Sheehan, P. Tegart, G. (Eds.) (1998) Working for the Future: Technology and Employment in the Global Knowledge Economy. Victoria University Press.

Footnotes:

[1] OECD. (1996) The Knowledge-Based Economy, OECD Paris, p. 16. [Internet] Available from: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/51/8/1913021.pdf [Accessed 20 August 2008]

[2] Hatzichronoglou, T.(1996) Globalisation and Competitiveness: Relevant Indicators, STI

Working Paper 1996/5, OECD, Paris, p. 7.

[3] Cantwell, J. In: DTI (1999) Economics of the Knowledge Driven Economy, Conference Proceedings, Department of Trade and Industry, London.

[4] DeVol, R.C. (1999) America’s High-Tech Economy: Growth, Development and Risks for Metropolitan Areas, Milken Institute, Santa Monica

[5] DTI (1999) Economics of the Knowledge Driven Economy, Conference Proceedings, Department of Trade and Industry, London, p.5

[6] Industry Canada (1997) Towards a Society Built on Knowledge [Internet} Available from: http://strategis.ic.gc.ca/SSG/ih01644e.html [Accessed 20p August 2008]

[7] DTI (1999) Economics of the Knowledge Driven Economy, Conference Proceedings, Department of Trade and Industry, London, p. 6.

--