The last time I ran a race in the Cascades my emotional and mental state were in a dark place, and I hadn’t fully accepted the toll losing one of my best friends was having on me on so many levels. What started out optimistic about a sub-24h finish at the 2023 Cascade Crest 100, turned into a mental and emotional meltdown and slog into the finish. Glad to have completed it, but far from what I’d consider a successful race, and what continued to be a challenging grieving process. 2024 found me battling back from severe sciatic nerve pain, and after 6months of not running, just being happy to be back on trails again, racing being far from a focus.

Flashforward, spring of 2025 Abby pitched the idea of the Dark Divide 100km in Washington and it piqued my interest, but not quite enough to get me to pull the trigger right away. The idea of a remote, super low key, adventurous wilderness run was what I was searching for. As Spring turned into early Summer and the calendar got packed full of running adventures; Big Bend NP, Hawaii, Four Pass Loop, Great Basin NP, Hardrock and High Lonesome pacing, I realized I was actually in pretty decent shape and with a 6week training block would feel ready to race again. So, Abby and I started talking logistics for Dark Divide (of which there were many). Plans were in motion, Airbnb options were being researched, flights booked, rental cars reserved but many more questions remained.

The Dark Divide Roadless area is a remote region of Southern Washington, sitting right between Mt Rainier, Mt St Helens and Mt Adams. The 76,000acres of wilderness is definitely one of the lesser-known areas of the Cascades, but boasts the same lush deep forests, craggy volcanic summits and sweeping ridgeline views that make the rest of the Cascades so magical. Long remote sections of rugged trail, steep climbs, technical descents, gratuitous summit tags, and lots of amazing views were promised to all runners. The 100mi race was in it’s 4th year, while the point-to-point 100km race was to make its debut in 2025. Being a point-to-point (>2h drive end to end) the pre-race logistics were a challenge, especially since there was no lodging at the finish. It quickly became evident that RD hadn’t fully considered this challenge after he was unable to secure a race shuttle service, so it left Abby and myself (along with many other racers) stressing the week before the race trying to cobble together a plan. Thankfully we were able to get it all sorted out, thanks to some amazing pacers/crew. After a smooth flight and drive down to Randall, things were in motion (more on logistics at the end).

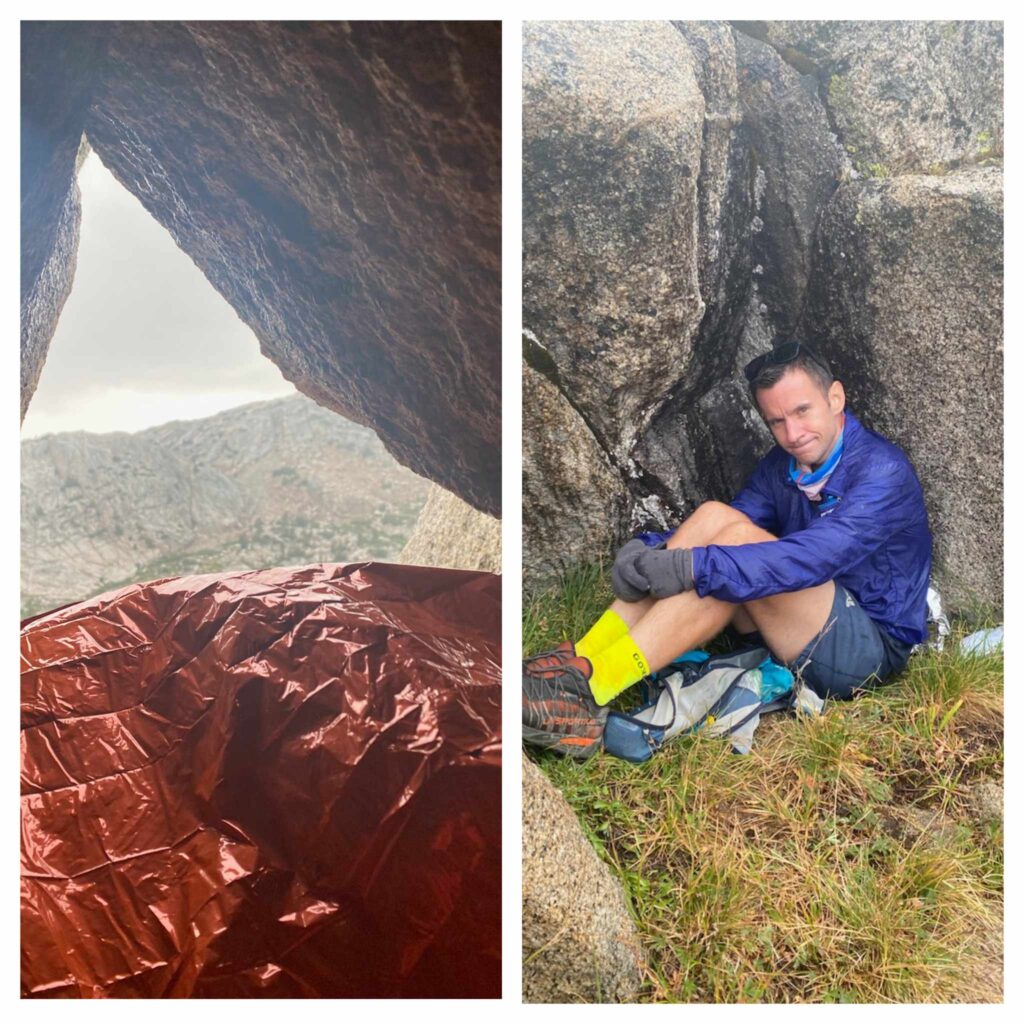

On Friday before the race we deposited our drop bags at the finish as the Cispus Learning Center and hopped in with our “chauffeur” Korrine for a 2h ride to the 100km start line at Wright Meadows, the nearest ‘city’ being Cougar, WA and it’s 113 people, 75min away. We arrived at Wright Meadow a little before sunset, set up our camp and chowed down on the cold dinner we’d packed. I caught up with James Varner for a bit as he manned the Aid Station for the 100mile runners (we started at their mm52). The RD rolled in a little after 7p for the ‘race briefing’, which was truly brief and a little all over the place, but very much encapsulated the low-key homegrown nature of the race. We crashed out soon after, Korrine and I in our tents, Abby and Stephanie in the car, ready for our 4am wake-up alarm.

I slept better than expected, and when the alarm went off, was up and straight into my pre-race preparation and routine. Get dressed, eat 2 poptarts, drink some water, sunscreen, get the muscles moving and spend some time recentering myself. The race wasn’t about redemption or proving anything to myself, it was about soaking in the experience, treasuring the reasons I started running (adventure and joy) and embodying the lessons Bailee had taught me over many years of friendship; approach everything with love, embrace every experience (good and bad) and don’t take any of it for granted. Just after 5am the RD counted down 3-2-1 GO and we jogged off into the warm early morning hours, four of us forming a lead pack from the start as we cruised down 2000ft to the Lewis River below. The downhill was quite pleasant, and we quickly found ourselves popping out of the forest onto a dirt road with signage pointing in two directions. Instinctually we continued straight ahead, but quickly realized this was not where we needed to be going, and a check of the map showed up doubling back along the road to the Aid Station, BEFORE continuing on the single track. After the Lewis River AS (mm5.4, 0:55) we continued on in the early twilight hours as the trail rolled upwards, until we abruptly hit the 1000ft climb to the Quartz Butte AS (mm14.2, 3:00).

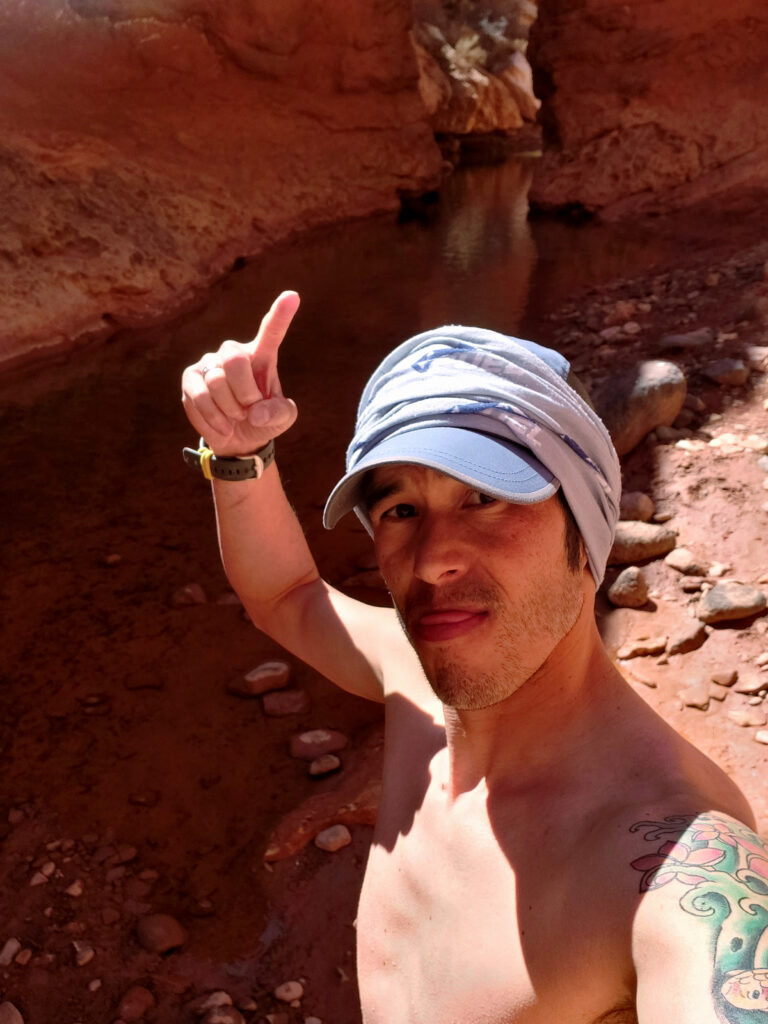

From Quartz Butte AS it was up to the ridgeline, where we’d stay for the next 28mi. I pushed the climb to the top of Quartz Creek Ridge, then continued to roll the forested section over to Prairie Summit AS well ahead of schedule (mm20.4, 4:40). I stocked up on food and filled my bottles for the long 11.4mi stretch over to Sunrise, though I made a critical error not filling my third water bottle. The trail rolled from deep sweltering forest to sunbaked alpine terrain as we traversed our way towards the Sunrise AS. The heat of the day started to take its toll, and I very much regretted only taking 2 water bottles with me for the long stretch. The final uphill before the Sunrise AS was the somewhat ridiculous mini climb up Jumbo Peak, where we were told to climb the stupid steep avalanche slope until we hit an ‘obvious sign’ to turn around, but not summit. Alex and I slogged our way up the 40degree dirt slope along with two other 100mi runners, reaching a confusing sign that only said “Futility”, unsure if we were supposed to stop, we continued upwards into the blueberry bushes. After another few minutes we saw no other signs of a course, so three of us flipped, while Alex decided to top out because he was only 100ft from the summit. So back down the steep dusty slope we went, sliding in “Futility” down the 4-6” of dust that covered our “Trail”. I plodded onwards, rapidly dehydrating in the midday sun, finally reaching the 1mi descent into the AS. I rolled into the Sunrise AS fully cooked, very dehydrated and needing to refuel (mm31.8, 7:40).

After chugging several cups of Tailwind, eating a piece of salted watermelon and half a quesadilla, I started back uphill, again forgetting to fill my 3rd bottle, DOH. The climb to Sunrise Peak was a slog, as the exposed sunbaked alpine terrain started to wear on me, made more challenging by the deeply rutted and overgrowth trail up to the summit. I plopped down on the summit for a quick breather and to have my first mini-pity party of the day. Then, back down the trail, passing Alex and Ian on the out and back, continuing on the high traverse toward Juniper Peak. The skies were hazy from all the West Coast smoke, but the views were still spectacular along the ridge, making the death march go by a bit easier. After a quick side trip up Juniper Peak, still in death march mode, I pushed myself downhill to the Juniper Aid Station, set on taking a few minutes to rebalance (mm41.1, 10:05).

I sunk into a chair at the Juniper AS, chowed down on a bowl of heavily salted watermelon as I chugged Tailwind. After consuming my delicious meal, I started the power hike up Tongue Peak. I hiked along at a steady pace as my body started to rehydrated and rebalance. I topped out on Tongue Peak (mm42.7, 10:55), still a bit lethargic, but starting to pep up. So, I stashed my poles and started the 3300ft descent to the Yellow Jacket AS, losing 2500ft in the initial 2.2mi! My legs were slowly gaining strength and I was able to hold a steady yog down the insanely steep, loose and rutted trail. It was actually a relief when the trail finally ended at the gravel road and I could just turn over the legs for a bit without worrying about footing. I forced myself to jog the final 1/2mi up to the Yellow Jacket AS (mm49.1, 12:10) where Ruth greeted me with my drop bag and the offer of food before the final big climb.

I drank some ginger ale, ate half a piece of white bread and started the long 4000ft slog up Burly Mountain right as 3rd place (Ian) rolled into the AS. I pushed up the climb to the best of my ability, but my legs were sluggish this late in the race. The climb was a steep grind up through the forest, at one point gaining 2000ft in 2mi. Ian caught me about halfway up the climb and put a gap on me to the summit. Though steep, the single track was mostly smooth, promising a speedy downhill. Finally, at 4000ft elev I popped out on the dirt road, the final 3mi to the summit only gaining 1300ft. My legs found their extra gear and I was able to crank out 15-16min/mi all the way to the summit. I passed John (1st place) coming down about 1mi from the top and Ian (2nd place) a few minutes from the AS, cranked my way to the lookout, allowing myself to pause to take in the breathtaking view. The sun was just setting, the smoke-filled air glowed orange and red, the valleys were filled with low clouds and expansive views greeted us in all directions. It was quite a scene to finish with, but I could only pause for a minute, rushing back to the aid station to grab some coke and water, turning down all solid food and rushing downhill to give chase to Ian, who was only 5-10min ahead.

I took off down the road at a steady clip, trying to click off miles as fast as my legs would move. As I descended into the trees the evening light waned and I flipped on my waist light. I passed 4th and 5th place far down into the trees, so knew it was only a race for 2nd/3rd. I dropped onto the single track and started to hammer down the 1000ft/mi descent giving chase to the lights far below. I blew past Abby and Ruth, gave a quick right-on, only later realizing she was first woman! I pushed the pace as much as I could, but once we got onto the Curtain Falls trail, the footing became quite technical and I had to slow WAY down. I passed behind the falls, hiked up the short hill and continued to casually jog the final mile to the finish, knowing Ian was too far ahead to catch. I popped out of the woods, rounded the pavement and cruised across the finish line, finishing in 15h42min, about 7min back of Ian in 2nd (but 1st Masters). My quads were sore, my knee was tight, feet beat up, but I felt good about the adventure, the effort and the experience the Dark Divide 100km had brought. I swapped war stories with fellow Coloradans Jon, Kevin and David who had all finished the 100mi Saturday evening. Abby finished several hours later in 18h 30min, 1st female, 7th OA and new course record holder, totally stoked on the accomplishment!

After chowing down on some soup, chili and snacks we stiffly limped our way back to the car and the Airbnb to get some sleep. Reflecting back, it was exactly what I needed in a race; remote, wild, more adventure run than race, alpine ridges, summits, deep lush forests, waterfalls, smooth rolling forest dirt, steep technical descents, some logistics to be improved, a home growth local event, with a passionate RD who was simply stoked to have new people experience an area he loved dearly. If this type of race vibes with your spirit and style, I highly recommend any of their distances; 50k, 100k, 100mi, just don’t expect crowds, big elaborate aid stations, beer gardens or a party, just beautifully rugged trails and good community all around.

Race Logistics and Thoughts: The race takes place in a remote region of the South Cascades between Mt Rainier, Mt Adams and Mt St Helens. The nearest towns are Randall and Packwood, with a population of just over 1000, a few restaurants and markets and a handful of lodging places. As of 2025 the race finish line, drop bags and head quarters for all races are at the Cispus Learning Center near Randall. The start line for the 100km race is >2h away near the Craggy Peak TH off NF-9328, with race briefing the night before the start, basically requiring one to camp out at the trailhead the night before the race in the large dirt field near the aid station (there is NOTHING nearby). Pre-race information, meetings and communication is minimal, though the RD Sean was very responsive when we emailed him. Course markings were mostly adequate, though with minimal differentiation between races and some confusing intersections, having the route on your phone and watch is basically mandatory. The trails themselves were all very easy to follow; with some being smooth dirt, others being steep dusty dirt bike trails and some steep loamy PNW dirt. Aid stations were generally well stocked with all the basic amenities; fruit, candy, sandwiches/wraps, quesadillas, ramen, walking tamales(?!?), Spring Energy and Tailwind. This year there was no live runner tracking due to inadequate tracker service/connection, so they were scrapped at the last minute, the RD hopes to have them for future races. For those wanting pacers and crew, the remoteness of the race makes times between aid stations long, driving slow and mostly on bumpy dirt roads, so be prepared to do a lot of slow driving, away from a comfy house and a cross-over/SUV is highly recommended though not necessary. Overall, if you treat Dark Divide as a remote wilderness race with small but very adequate support you won’t be surprised.