*Originally posted 12/26/2010 + 12/24/2017. Merry Christmas.

imaginary outfit: jólabókaflóð 2025 + wish-listed books for 2026

The train snakes through the icy mountains, its steady, churning roar breaking the quiet of snow-stilled space. Inside, the traveler gazes idly out the window into the darkening world. An eight-rayed star and glittering snowflake shine from the shoulder of her structured copper cardigan, while wooden adornments dangle from her ears and circle her finger. Slouchy velvet trousers break for a gleam at the ankle, like the rare green flash of sunset, paired with a peculiarly sensible pair of soft shearling shoes. She taps one silvered nail against the glass, then reaches down into a startlingly capacious bag, crammed with things to read. She pulls out a gleaming metal book and opens a marble box of sharpened scented pencils. After ringing the buzzer for a pot of tea and a fresh pear, she turns her attention again to the bag.

Inside, there is Edmund de Waal's "book about archives that is itself archival," Bridget Penney's recreation of a book that "contained enclosures ... and that encompasses all that can be captured through the filter of the writer's gaze and mind," and writings by Jenny Erpenbeck on things that disappear. There is Paul Willem's The Cathedral of Mist, telling of "the emotionally disturbed architectural plan for a palace of emptiness; the experience of snowfall in a bed in the middle of a Finnish forest; the memory chambers that fuel the marvelous futility of the endeavor to write; the beautiful woodland church, built of warm air currents and fog, scattering in storms and taking renewed shape at dusk," and a novel by Maurguerite Young that David Shurman Wallace asserts "eschews any stable sense of reality." He described his emotions reading it:

As I waded through dense paragraphs of long, winding sentences filled with images of stars and waves and angels, of seagulls and silk and butterflies, of dreams and illusions and any other abstraction you can imagine, occasionally I felt angry—on a personal level—at what I took to be the book’s obstinacy, its willingness to reprise what it had said hundreds of times before, not to mention the seemingly endless detours that defy any obvious sense of structure. At other moments, I knew that I was immersed in something beautiful and strange, something too big to understand all at once.

There is also a rare collection of Young's essays with her 1945 piece, "The Midwest of Everywhere," because this is a place, too, that the traveler calls home:

For me, a plain Middle Westerner, there is no middle way. I am in love with whatever is eccentric, devious, strange, singular, unique, out of this world—and with life as an incalculable, a chaotic thing, meaningful above and beyond the necessary and elemental data of my subject ... I am told by commentators both cynical and wistful, those who have never inhabited my regionless region, that we of the Middle West have no Main Stream, no focus, no elite. 'True,' I would answer, 'the Middle West, though it may have a hidden Gulf Steam, has no Main Stream because it is oceanic'—that is, touching on all shores and limitless. There are no boundaries I know of. I have seen, on the grassy ocean, many a lurching ancient mariner—and once, in an Indiana cornfield, a dead whale in a boxcar.

The Middle West is probably a fanatic state of mind. It is, as I see it, an unknown geographic terrain, an amorphous substance, the ghostly interplay of time with space, the cosmic, the psychic, as near to the North Pole as to the Gallup Poll.

There are more hefty tomes to consider: a "death-defying feat of ambition ... a spectacular honeycomb of books within books" and a 544-page monograph on Celia Paul, which recalls to the traveler's mind an afternoon in an airy London gallery being held by painted eyes. A unforgettable exhibit of Surrealist and Romantic work is catalogued, as is "five centuries of stars, dreams, and plenilunes" and 2,000 Japanese rain words. Smaller books fill the corners—late ghost stories by Henry James, a book of "melancholic, wandering castles," another with photographs of hands, and one tense with high-stakes mountain drama.

The traveler thinks. What does she want to read? After all, it is Christmas Eve. Finally, she finds what she is looking for—a book of Yuletide hauntings.

Merry everything, friends.

*

Other jólabókaflóðs (Yule book floods).

*

TOGA PULLA Motif cardigan / Album di Famiglia velvet W & S trousers / Susan Hable ebony drop earrings / early Victorian carved bog oak mourning ring at Erica Weiner / Jean Gerbino cup and saucer, ca. 1950 / Lizzie Ames custom journal cover / Hender Scheme Mouton Henri shoes / Harry and David pears / Choosing Keeping x Perfumer H scented pencils / Maria La Rosa Verdino laminated socks.

Labels:

books,

christmas,

imaginary outfit,

jólabókaflóð

candle, snowflake, gingerbread, angel

*

Cecelia Glasher's sketches of snowflakes, ca. 1855.

*

A New York tree in winter, via Anonymous Works.

*

Fruit bowl carved by Robert "Mouseman" Thompson, ca. 1950s.

*

From Listen and Hear by Kathleen Shoesmith, 1973, via stopping off place.

*

*

*

A recipe for gingerbread ca. 1395 and gilded gingerbread and mold. The Fitzwilliam Museum.

*

Peter Doig, untitled watercolor, 1999, via le jardin robo.

*

*

Wilson Alwyn Bentley, snow crystal ca. 1910.

*

Merry everything, friends.

books that could be good gifts, depending on who you give them to

The holiday season is careening toward culmination—candles lit, songs sung, gifts exchanged, a new calendar unwrapped—and as usual I don't feel ready.

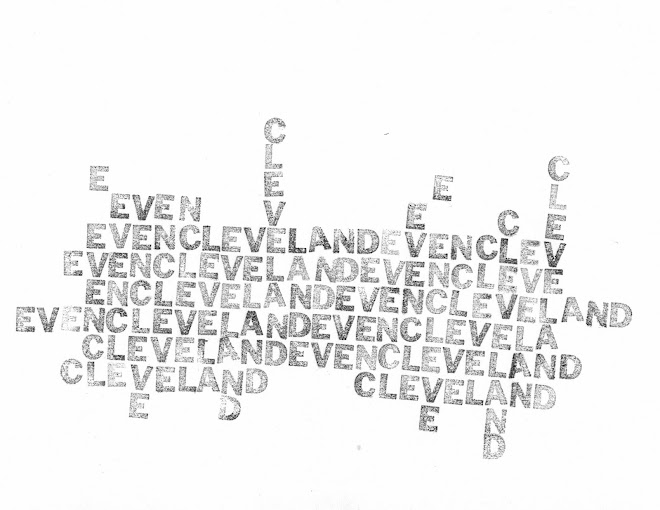

(That's me above: the blockhead groping her way toward 2026.)

To steady myself, I like to look at my books, because they hold time differently. With stacks around me, I am rich in options: each book a door, each door a different future. And the books are patient, waiting for the moment when, for obscure reasons, I am ineluctably compelled to pick up the book a friend gave me three Christmases back or that one I bought for $.50 at a library sale, start reading, and feel my whole self electrified with thought and art.

(I tend to roll my eyes when people get breathy about BOOKS and WRITING and the POWER OF WORDS, but damn if it isn't true.)

Anyway, this is why I think books are the most exciting gifts. Here are a few I'd recommend.

For picture-book lookers, any age:

Any book by Tana Hoban, maker of the best photographic picture books. Hugh and I were particularly fond of Shapes, Shapes, Shapes, Is It Red? Is it Yellow? Is it Blue?, Is it Larger? Is It Smaller?, and Red, Blue, Yellow Shoe.

For bedtime-story listeners:

Giovanni Rodari's Telephone Tales: "Every night, at nine o’clock, wherever he is, Mr. Bianchi, an accountant who often travels for work, calls his daughter and tells her a bedtime story. Set in the 20th century era of pay phones, each story has to be told in the time that a single coin will buy."

Grace Lin's Where The Mountain Meets the Moon, the story of Minli, who leaves the Fruitless Valley to find the Old Man of the Moon.

For struggling artists:

Randall Jarrall's The Bat Poet, which Elizabeth Hardwick described as "a haunting little story, a parable of charming instruction—and of instructive charm." It tells of a bat who sees what other do not and has to learn what to do with that knowledge, gently dipping into questions of poetic meter, criticism, and craft.

Rumer Godden's An Episode of Sparrows, the story of trying to realize a creative vision and how support can make all the difference. (More about it from me here.)

For anyone longing to draw the sun:

Bruno Munari's Drawing the Sun.

For lovers of November walks among tatter-leafed trees:

In Wildness Is the Preservation of the World, excerpts from the writings of Henry David Thoreau, selected by Eliot Porter. Porter's quiet photographs of the natural world capture the stillness of ephemeral places in a way that pierces the soul. (There is a new edition by Chronicle, which is fine, but the original edition, designed by David Brower, is miles better.)

For museum wanderers:

John Berger's Portraits, a collection of essays about artists which in its scope and variety of forms is akin to wandering an expertly curated gallery of the mind.

For New Yorkers in exile:

The WPA Guide to New York City, a time-machine and teleportation device disguised as a book. Compiled and published in the 1930s as part of the New Deal effort to keep writers and artists employed, it captures the bones of the city as it was then, a skeleton still visible in many places, through capsule histories of neighborhoods, buildings, and services. (It is also how I discovered the amazing House-Number Key to Manhattan.)

For bourgeois anarchist cooks:

The transporting, mesmeric, fabulous, and maddening Honey From a Weed by Patience Gray. In her forties, the English-born Gray upended her comfortable life as a successful cookbook author to follow the sculptor Bernard Mommens to the Mediterranean. In his quest for stone, they lived in remote areas of Greece, Italy, and Spain, and Gray committed herself to rural life, absorbing and recording a dizzying array of culinary folkways. The book, published in the mid 1980s, is absolutely singular—reminisces of seasonal feasts and meetings with rare book collectors sandwich a chapter on anarchy—and crammed with a plethora of extremely specific, plainspoken recipes that range from the simple to the terrifyingly time-intensive. (One that requires poking the seeds out of grapes with a pin haunts me.) Gray's unsentimental admiration for the resourcefulness of the communities she lives in is obvious, and yet much of what she admires is a reality shaped by brutality—foraging less as a delightful diversion and more as a desperate need to make as many things as possible palatable.

Print out Angela Carter's 1987 LRB review, which digs into the uneasy question of Gray's privilege, as a side dish:

The metaphysics of authenticity are a dangerous area. When Mrs Gray opines, ‘Poverty rather than wealth gives the good things of life their true significance,’ it is tempting to suggest it is other people’s poverty, always a source of the picturesque, that does that. Even if Mrs Gray and her companion live in exactly the same circumstances as their neighbours in the Greek islands or Southern Italy, and have just as little ready money, their relation to their circumstances is the result of the greatest of all luxuries, aesthetic choice.Offer Pulp's "Common People" as an apéritif.

For people who experience transcendence listening to Philip Glass:

The Philip Glass Piano Etudes Box Set, a printed object to treasure forever.

For solo francophiles:

French Cooking for One by Michèle Roberts, a beguiling and practical mix of memoir and microfeasts.

For women who want it all:

Family Happiness by Laurie Colwin. Polly Solo-Miller Demarest has more than enough— a loving if overworked husband, two charming children, a close (maybe too close) extended family, a fulfilling job, a fabulous apartment, access to a vacation spot. She is meeting expectations. She should be happy. She is happy. And yet ... maybe she wants something more? Colwin is so terrific at rendering humans on the page, WASP-ishly frayed collars and all, that reading this book feels like crashing a great party, and WHAT AN ENDING. I am deeply aggrieved that no female filmmaker of the 1980s or '90s made this into a movie (paging Joan Micklin Silver), because it deserved to become a repeat-watch classic.

For lovers of Victorian gossip:

Five Victorian Marriages by Phyllis Rose digs into the savory eye-popping marital foibles of Thomas and Jane Carlyle, Effie Gray and John Ruskin, Harriet Taylor and John Stuart Mill, George Eliot and George Henry Lewes, and Charles and Catherine Dickens. It is redolent with the inimitable tang of actual books-in-stacks library research, distilled through Rose's wry, subtly opinionated sensibility.

For the handsy:

Jeux de Mains by Stephen Ellcock and Cécile Poimbœuf-Koizumi, a book that must be handled carefully, as the credits for its 100 images of hands lie hidden within the French-folded pages.

For undead grammarians:

The Deluxe Transitive Vampire: The Ultimate Handbook of Grammar for the Eager, the Innocent, and the Doomed by Karen Elizabeth Gordon, to enliven the study of a languishing art.

For zombie-fanciers:

It Lasts Forever and Then It's Over by Anne de Marcken. Perhaps the only book I have ever read where the protagonist ends up decapitated and yet the narration carries on.

For death-defiers:

Elias Canetti's lifework, The Book Against Death, and Douglas Penick's retelling of the Vetala Panchavimshati, The Oceans of Cruelty: Twenty-Five Tales of a Corpse Spirit (both discussed here).

Also Jenny Erpenbeck's The End of Days, a book where the protagonist dies again and again.

For practical gardeners:

Bill Neal's Gardener's Latin, an invaluable little volume that decodes plant tags.

For unsentimental Ohioans (and anyone who appreciates fantastic novels):

Dawn Powell's My Home is Far Away. Gore Vidal, in a killer 1987 profile in the NYR, says "For decades Dawn Powell was always just on the verge of ceasing to be a cult and becoming a major religion." Reading this novel was my conversion experience.

For unforgettable tales of murderous and mysterious boarding school life:

Our Lady of the Nile by Scholastique Mukasonga and Picnic at Hanging Rock by Joan Lindsay.

For seasonal dressers:

Fletcher's Almanac: Nature Encounters and Fashion Systems Through the Year by Kate Fletcher, a singular tying of the sartorial to the seasonal that includes advice like "use the winter months to enlarge the pockets of your clothes" and "practice seeing fashion shows and collections as imitations of breeding displays and nesting activity" and links crop tops to spider silk.

For ambitious readers with short attention spans:

Hanuman Editions, tiny works of avant-garde writing.

For the pathologically nostalgic:

The Good Old Days: They Were Terrible! by Otto L. Bettmann which cheerfully and thoroughly demolishes the notion that the past in the United States was ever, in any way, better. (More about it here.)

For puzzle freaks:

For the ruin-minded:

Rose Macauley's The Pleasure of Ruins, "an inquisition into the images, philosophy, theology, archaeology and literature of ruin. And, moreover, it is a book that allows its subject matter to infect its logic and form: it is a sprawling and enigmatic work; an excessive and truly stupendous book." (Look for the massive hardcover edition.)

For sky-gazers:

Ad from the New Statesman and Nation, March 2, 1940, via The Silver Locket.

Labels:

books,

gift guides

gifts for magazine-stackers, ephemera-hoarders, and other lovers of work in print

The ultimate in reading stands, by Bruno Mathsson.

Synonym, a magazine that tells immigrant stories through food.

To mark a place, Lucky Star Candle's burnable bookmark braid.

Fornasetti's Libri magazine rack, because of the key, the butterfly, and the tasseled bookmark.

COMBO, an annual magazine "conceived as an archive of our collective dreams."

Louie Issaman Jones' sculptural bookstand, designed to display spreads.

Word Making and Taking, the 19th century's favorite word game, via Haec City / Also Books.

Maggie Umber's Sound of Snow Falling, a visual diary of great horned owls.

"A piece of glass" by Derek Sullivan: "a publication to hang in a window, a bit of wonder when conditions permit" at Paul + Wendy Projects.

Archival boxes, for keeping rare pieces.

Sounds for Focus & Productivity, a zine by Sun-Rom and AURAGRAPH that comes with a risograph-printed poster for the wall and a flexidisc for the turntable.

The Brick Journal, "a collaborative publication devoted to the visual language, social and geologic histories, and cultural production that stem from and connect to brickmaking and brick work."

Alan Sobrino's epistolary novel sent by mail, via five handwritten letters imagining the sexy correspondence Valmont and M. Merteuil of Les Liaisons Dangereuses.

Alica Nauta's Reference Library Files, a book that documents looking for images at the Toronto Reference Library.

Jewelry for books, by Fixed Air.

Bundle Theory, an essay by Romy Day Winkel published by OUTLINE on "collecting, or hoarding, as an aesthetic of patiences."

Morgan Ritter's wearable poems, "curious tags [that] may be integrated into your life as plainly as the branded tags on the interior of your garments."

A wheely silver Hulken bag, for schlepping finds home from library sales and art book fairs. (I have this and love it so, so much.)

Not pictured: Gift certificates to a magazine/zine-focused store, like Chess Club or The City Reader in Portland, Oregon, Periodicals in Detroit, Paper + Dirt in Pittsburgh, Hi Desert Times in Twentynine Palms, the Heath Newsstand in San Francisco, Tomo in Austin, Quimby or Inga in Chicago, and in New York City, Bungee Space, Casa, Head Hi, Iconic, Magazine Cafe, and Printed Matter. Alternatively, a subscription to Stack, Steven Watson's marvelous magazine subscription service, which delivers a different independent magazine from around the world each month.

Finally (though truly, this list could go on forever): Marcell Mars' manifesto:

In the 1990s, activist, independent scholar, and artist Marcell Mars founded Memory of the World / Public Library amidst the ruins of the former Yugoslavia, with the aim of resisting the privatization of knowledge and encouraging everyone to freely share books online.

B09k’s poster work is a re-enactment of Mars’s Public Library manifesto,

“When everyone is a librarian, the library is everywhere,” inviting everyone to participate and become part of the world’s memory.

*

Okay, one more idea/shameless plug: magazines about sound and emotion, mushrooms (1 + 2), and cats, edited by yours truly.

Labels:

art supplies,

books,

gift guides,

periodicals

gifts for wildly creative ten-year-old goofballs

For medievalists/miniaturists: a decorate-your-own castle blank, complete with inspiration, craft glue, and an assortment of craft paints and popsicle sticks (old egg cartons make especially good masonry). Add a working catapult kit for siege warfare re-enactments.

For painters: Akashiya watercolor brushes and a big ol' New SoHo SKETCH pad.

For creative writers: A fuzzy one-eyed creature journal, complete with padlock, for monstrously good drafts.

For sculptors: Wikki Stix (a magical melding of yarn and wax) to doodle in three dimensions.

For activists: The Pushcart War by Jean Merrill, which reveals (hilariously and metafictionally) words to live by —"don't be a truck"—and what it really takes to change the world.

For collectors: An earmarked ten-spot tucked inside a coin purse for treasure-seeking expeditions, jaunts to the candy shop, or bookstore adventures.

For recipe tinkerers: Extremely good cocoa, fluffy marshmallows, a whole can of real whipped cream, and Dutch chocolate sprinkles, for concocting the ultimate hot chocolate.

For composers: A pocket-sized Stylophone synthesizer for sonic noodling.

For the late-night button-pusher: A Snoopy Timex, complete with stopwatch and backlight.

For cuddlers: Fuzzy slippers with kitten ears in pink or brown.

For the hoarder of Jellycats: A Raindrop.

For all: Kiosk's "noisemaker from hell", because the holidays come but once a year (and because, despite its fearsome appearance, it only makes a subdued squeak, haha).

Labels:

art supplies,

books,

gift guides,

musical instruments,

shoes,

toys,

treats,

watches

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)