A brief essay on the limits of science

Science anchors itself in empiricism. Theory is important—vital. That’s the facet of science that interprets empirical observation; it puts all the things measured or observed in nature into a coherent and useful picture of what’s going on. But without those measurements, without the test of events in the world, the most beautiful theory is a pleasing fiction that might some day become fact.

All of which is a long winded way of saying that science is all about making sense of the real world as it is, not as anyone might wish it to be. And that is both its strength and, certainly now, in the second week of the latest Trump era, its singular weakness

For example: check out this excellent Financial Times feature on policy approaches to birthrates and fertility.

TL:DR—direct pro-natalist moves don’t work, or aren’t anywhere near effective enough:

Politicians in Lestijärvi thought they had the answer to Finland’s demographic woes: each mother of a newborn baby would receive €1,000 a year for 10 years if they stayed in the Nordic country’s second-smallest municipality. But more than a decade after they introduced the payments, and over €400,000 poorer, officials were forced to concede defeat: Lestijärvi’s population has shrunk by a fifth since the scheme started. “It wasn’t worth doing at all,” said Niko Aihio, the town’s former head of education. “The baby boom only lasted one year.”

The piece goes on to say that similar moves in large countries and small. from China to Singapore and many in between, have been similarly ineffective. Again, according to the reporters, two thirds of the world’s population now lives in countries reproducing below replacement—and that includes not just the rich nations but in jurisdictions across the income spectrum. And their sources predict that the fertility drought will deepen across the 21st century. This matters for a bunch of reasons, but especially destabilizing is the impact such a demographic shift would have on old age. Fewer kids means fewer people of working age available to support their retired elders, which in turn creates multiple failure modes for democratic and authoritarian polities alike.

So far we’re firmly in the empirical zone: birth rates now can be measured, and (to bring a bit of theory into the mix) models can be built to test the range of future possibilities. So we know this much: women around the world are having fewer children than they used to, and direct incentives to change that have proved ineffective—or at best, insufficiently effective, in that they can raise birth rates (as in South Korea for example) but not enough to alter the underlying demographic trajectory.

Now comes the tricky part: what might work better?

One response, as the reporters (Eade Hemingway, Janina Convoy, and Richard Milne) write, requires rethinking what it means to be pro-natalist or pro-family:

Yet, while personal choice has played a part in the global decline in childbearing, studies indicate people are often having fewer children than they would like to — indicating there could still be a role for public policies in changing that.

Barriers such as the cost of childcare and housing, financial instability, persistent gender inequality, inflexible working conditions, and a lack of job security are among the factors holding people back from having more children.

That is: thinking that the solution to getting a woman to have more babies is to pay them to do so—an atomistic homo/femina economicus/a approach—is at best effective on the margins. Thinking of women, children, and families as part of society points to a different possibility. The writers add that the importance of social circumstances goes beyond spending on direct incentives for childbearing, as one of their sources said: “good local services — such as libraries, swimming pools and decent childcare — seemed more important than money in encouraging women to have babies.”

So: what’s required to encourage the birth of more children, this story argues, is not a Kinder, Küche, Kirche expectation that young women should aspire to trad-wife roles and nothing more, but support for a pro-child and a pro-civic approach to building a society.

And here we run smack into the limits of science. It’s possible to establish demographic facts: fertility rates are knowable. It’s possible to make inferences both as the trajectory of such rates and the evolving age structures of societies experiencing childbirth below replacement. It’s possible to perform policy experiments—all those incentive programs in different places—and measure their impact. And finally, it’s within the scope of scientific reasoning to propose interpretations of those experimental results.

And that’s it. Just because it might make sense on the basis of such data to, say, encourage the spread of libraries and other public spaces doesn’t mean that the current US administration will do so, much less as create an infrastructure that would make it easier for women to both raise kids and pursue a career.

Those in the world of science, and in some ways even more those of us in the subgroup focused on communicating science to the public .have had to learn this obvious but hard lesson: reality on its own is not enough. Never has been. A scientifically informed approach to policy needs to be married to power to have a chance. Again, that’s a PGO. But it is one that seems to need to be relearned over and over again.

Just to drive that point home: beyond encouraging women in any given country to have more kids, rich countries enjoy another, simple and immediately available solution to the problem of finding enough workers to support the elderly. It’s another obvious thought: if there aren’t enough babies being born in, say, the US, to cover Social Security for our increasingly aged society, then let folks from elsewhere in.

We see how that’s going right now.

Check out the FT story. That’s a sharing link good for all of three clicks. After that, I’m afraid, y’all will have to find your own way in.

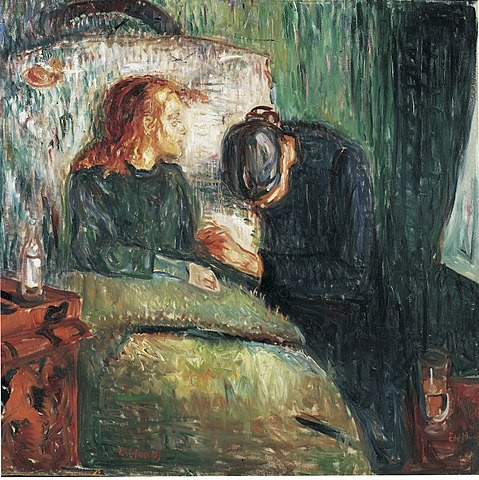

Image: Mary Cassatt, Sleepy Baby, 1910

Recent Comments