Laissez venir à moi les petits enfants, et ne les en empêchez pas; car le royaume de Dieu est pour ceux qui leur ressemblent. Jésus (Luc 18:16)

Laissez venir à moi les petits enfants, et ne les en empêchez pas; car le royaume de Dieu est pour ceux qui leur ressemblent. Jésus (Luc 18:16)

Je vous le dis en vérité, toutes les fois que vous avez fait ces choses à l’un de ces plus petits de mes frères, c’est à moi que vous les avez faites. Jésus (Mathieu 25 : 40)

N’est-il pas écrit: Ma maison sera appelée une maison de prière pour toutes les nations? Mais vous, vous en avez fait une caverne de voleurs. Jésus (Marc 11: 17)

Lorsque l’esprit impur est sorti d’un homme, il va par des lieux arides, cherchant du repos, et il n’en trouve point. Alors il dit: Je retournerai dans ma maison d’où je suis sorti; et, quand il arrive, il la trouve vide, balayée et ornée. Il s’en va, et il prend avec lui sept autres esprits plus méchants que lui; ils entrent dans la maison, s’y établissent, et la dernière condition de cet homme est pire que la première. Jésus (Matthieu 12: 43-45)

Du passé faisons table rase. Eugène Pottier (L’Internationale, 1871)

O Enfants d’Israël ! rappelez-vous la faveur que Je vous ai octroyé, et remplissez vos engagements envers Moi comme Je remplis Mes obligations envers vous, et ne craignez personne d’autre que Moi. Et croyez en ce que Je révèle, confirmant la révélation qui est avec vous, et ne soyez pas les premiers à rejeter la Foi qui s’y trouve, ni ne vendez Mes Signes pour un petit prix; et craignez Moi, et Moi seul. Coran 2:40-41

Combattez ceux qui rejettent Allah et le jugement dernier et qui ne respectent pas Ses interdits ni ceux de Son messager, et qui ne suivent pas la vraie Religion quand le Livre leur a été apporté, (Combattez-les) jusqu’à ce qu’ils payent tribut de leurs mains et se considèrent infériorisés. Coran 9:29

Des théologiens absurdes défendent la haine des Juifs… Quel Juif pourrait consentir d’entrer dans nos rangs quand il voit la cruauté et l’hostilité que nous manifestons à leur égard et que dans notre comportement envers eux nous ressemblons moins à des chrétiens qu’à des bêtes ? Luther (1519)

Nous ne devons pas […] traiter les Juifs aussi méchamment, car il y a de futurs chrétiens parmi eux. Luther (Propos de table, 1543)

Si les apôtres, qui aussi étaient juifs, s’étaient comportés avec nous, Gentils, comme nous Gentils nous nous comportons avec les Juifs, il n’y aurait eu aucun chrétien parmi les Gentils… Quand nous sommes enclins à nous vanter de notre situation de chrétiens, nous devons nous souvenir que nous ne sommes que des Gentils, alors que les Juifs sont de la lignée du Christ. Nous sommes des étrangers et de la famille par alliance; ils sont de la famille par le sang, des cousins et des frères de notre Seigneur. En conséquence, si on doit se vanter de la chair et du sang, les Juifs sont actuellement plus près du Christ que nous-mêmes… Si nous voulons réellement les aider, nous devons être guidés dans notre approche vers eux non par la loi papale, mais par la loi de l’amour chrétien. Nous devons les recevoir cordialement et leur permettre de commercer et de travailler avec nous, de façon qu’ils aient l’occasion et l’opportunité de s’associer à nous, d’apprendre notre enseignement chrétien et d’être témoins de notre vie chrétienne. Si certains d’entre eux se comportent de façon entêtée, où est le problème? Après tout, nous-mêmes, nous ne sommes pas tous de bons chrétiens. Luther (Que Jésus Christ est né Juif, 1523)

Les Juifs sont notre malheur (…) Les Juifs sont un peuple de débauche, et leur synagogue n’est qu’une putain incorrigible. On ne doit montrer à leur égard aucune pitié, ni aucune bonté. Nous sommes fautifs de ne pas les tuer! Luther

Ou Dieu est injuste ou vous, les Juifs, vous êtes des impies (…) Il est un argument que les Juifs ne peuvent combattre (…) Il faut qu’il nous disent les causes pourquoi, depuis quinze cents ans, ils sont un peuple rejeté de Dieu, sans roi, sans prophètes, sans temple; ils ne peuvent en donner d’autres raisons que leur péchés. Luther

Si un juif vient me demander le baptême, je lui donnerai, mais aussitôt après je vous le mènerai au milieu du pont de l’Elbe, lui accrocherai une meule au cou et vous le jetterai à l’eau. Luther (Propos de table, 1543)

Dans les villes, ce qui exaspère le gros de la population française contre les Juifs, c’est que, par l’usure, par l’infatigable activité commerciale et par l’abus des influences politiques, ils accaparent peu à peu la fortune, le commerce, les emplois lucratifs, les fonctions administratives, la puissance publique . […] En France, l’influence politique des Juifs est énorme mais elle est, si je puis dire, indirecte. Elle ne s’exerce pas par la puissance du nombre, mais par la puissance de l’argent. Ils tiennent une grande partie de de la presse, les grandes institutions financières, et, quand ils n’ont pu agir sur les électeurs, ils agissent sur les élus. Ici, ils ont, en plus d’un point, la double force de l’argent et du nombre. Jean Jaurès (La question juive en Algérie, Dépêche de Toulouse, 1er mai 1895)

Nous savons bien que la race juive, concentrée, passionnée, subtile, toujours dévorée par une sorte de fièvre du gain quand ce n’est pas par la force du prophétisme, nous savons bien qu’elle manie avec une particulière habileté le mécanisme capitaliste, mécanisme de rapine, de mensonge, de corset, d’extorsion. Jean Jaurès (Discours au Tivoli, 1898)

Parmi eux, nous pouvons compter les grands guerriers de ce monde, qui bien qu’incompris par le présent, sont néanmoins préparés à combattre pour leurs idées et leurs idéaux jusqu’à la fin. Ce sont des hommes qui un jour seront plus près du cœur du peuple, il semble même comme si chaque individu ressent le devoir de compenser dans le passé pour les péchés que le présent a commis à l’égard des grands. Leur vie et leurs œuvres sont suivies avec une gratitude et une émotion admiratives, et plus particulièrement dans les jours de ténèbres, ils ont le pouvoir de relever les cœurs cassés et les âmes désespérées. Parmi eux se trouvent non seulement les véritables grands hommes d’État, mais aussi tous les autres grands réformateurs. À côté de Frédéric le Grand, se tient Martin Luther ainsi que Richard Wagner. Hitler (« Mein Kampf », 1925)

Le 10 novembre 1938, le jour anniversaire de la naissance de Luther, les synagogues brûlent en Allemagne. Martin Sasse (évêque protestant de Thuringe)

Depuis la mort de Martin Luther, aucun fils de notre peuple n’est réapparu comme tel. Il a été décidé que nous serons les premiers à être témoins de sa réapparition… Je pense que le temps est passé et que nous devons dorénavant dire les noms de Hitler et de Luther d’un même souffle. Ils sont faits tous les deux du même moule. [Schrot und Korn]. Bernhard Rust (ministre de l’éducation d’Hitler)

Avec ses actes et son attitude spirituelle, il a commencé le combat que nous allons continuer maintenant; avec Luther, la révolution du sang germanique et le sentiment contre les éléments étrangers au Peuple ont commencé. Nous allons continuer et terminer son protestantisme; le nationalisme doit faire de l’image de Luther, un combattant allemand, un exemple vivant « au-dessus des barrières des confessions » pour tous les camarades de sang germanique. Hans Hinkel (responsable du magazine de la Ligue de Luther Deutsche Kultur-Wacht, et de la section de Berlin de la Kampfbund, discours de réception à la tête de la Section Juive et du département des films de la Chambre de la Culture et du ministère de la Propagande de Goebbels)

Le Peuple Allemand est uni non seulement par la loyauté et l’amour de la patrie, mais aussi par la vieille croyance germanique en Luther [Lutherglauben]; une nouvelle époque de vie religieuse consciente et forte a vu le jour en Allemagne. Chemnitzer Tageblatt

Le nationalisme doit faire de Luther un combattant allemand. Avec ses actes et son attitude spirituelle, il a commencé le combat que nous allons continuer maintenant. Hans Hinkel (rédacteur de la Ligue de Luther. Deutsche Kuktur-Watch)

Là, vous avez déjà l’ensemble du programme nazi. Karl Jaspers

Il est difficile de comprendre le comportement de la plupart des protestants allemands durant les premières années du nazisme si on ne prend pas en compte deux choses : leur histoire et l’influence de Martin Luther. Le grand fondateur du protestantisme était à la fois un antisémite ardent et un partisan absolu de l’autorité politique. Il voulait une Allemagne débarrassée des Juifs. Le conseil de Luther a été littéralement suivi quatre siècles plus tard par Hitler, Goering et Himmler. William L. Shirer

Au Procès de Nuremberg, après la Seconde Guerre mondiale Julius Streicher, le fameux propagandiste nazi, éditeur de la revue hebdomadaire haineuse antisémite Der Stürmer, affirme que s’il doit être présent ici, accusé de telles charges, alors il doit en être de même pour Martin Luther. En lisant certains passages, il est difficile de ne pas être d’accord avec lui. Les propositions de Luther se lisent comme un programme pour les nazis. William Nichols

Nous qui portons son nom et héritage, devons reconnaître avec peine les diatribes anti-judaïques contenues dans les articles tardifs de Luther. Nous rejetons ses invectives violentes comme l’on fait nombre de ses compagnons au XVIe siècle, et nous sommes dans une profonde et constante tristesse pour ses effets tragiques sur les générations ultérieures de Juifs. Conseil des églises de l’Église luthérienne évangélique d’Amérique (1994)

Le peuple juif est le Peuple Élu de Dieu. Les croyants doivent les bénir comme les Écritures disent que Dieu bénira ceux qui bénissent Israël et maudira ceux qui maudissent Israël. L’Église désavoue et renonce aux œuvres et mots de Martin Luther concernant le peuple juif. Des prières sont faites pour la cicatrisation des douleurs du peuple juif, sa paix et sa prospérité. Des prières sont faites pour la paix de Jérusalem. Avec une grande tristesse et des regrets, une repentance est offerte au peuple juif pour le mal que Martin Luther a causé. Le pardon est demandé au peuple juif pour ces actions. Les Évangiles sont tout d’abord pour les Juifs et ensuite les Gentils (les croyants en Christ). Les Gentils ont été greffés à la vigne. Dans le Christ, il n’y a ni Juif ni Gentil, mais le désir du Seigneur est qu’il n’y ait qu’un seul nouvel homme, car le Christ a rompu le mur de séparation avec Son propre corps. (Éphésiens 2:14-15). Le LEPC/EPC/GCEPC bénit Israël et le peuple juif. The Lutheran Evangelical Protestant Church (Église protestante évangélique luthérienne des États-Unis)

Notre monde est de plus en plus imprégné par cette vérité évangélique de l’innocence des victimes. L’attention qu’on porte aux victimes a commencé au Moyen Age, avec l’invention de l’hôpital. L’Hôtel-Dieu, comme on disait, accueillait toutes les victimes, indépendamment de leur origine. Les sociétés primitives n’étaient pas inhumaines, mais elles n’avaient d’attention que pour leurs membres. Le monde moderne a inventé la “victime inconnue”, comme on dirait aujourd’hui le “soldat inconnu”. Le christianisme peut maintenant continuer à s’étendre même sans la loi, car ses grandes percées intellectuelles et morales, notre souci des victimes et notre attention à ne pas nous fabriquer de boucs émissaires, ont fait de nous des chrétiens qui s’ignorent. René Girard

Le XIX siècle a transformé Noël en une célébration de la famille bourgeoise. Il a du même coup installé l’enfant au centre du rite profane en lui attribuant un nouveau rôle, celui-ci étant révélateur du changement de son statut social et familial. D’acteur principal du rituel mettant l’adulte au défi, il est en effet devenu en un siècle et demi le récipiendaire d’un don infini et sans réciprocité. Martyne Perrot

L’antisionisme est le nouvel habit de l’antisémitisme. Demain, les universitaires qui boycottent Israël demanderont qu’on brûle les livres des Israéliens, puis les livres des sionistes, puis ceux des juifs. Roger Cukierman (président du CRIF, janvier 2003)

La nouvelle judéophobie se présente comme une saine réaction à l’injustice – la “spoliation” des Palestiniens, des musulmans, de tous les peuples victimes de l’“arrogance” occidentale. Aussi est-elle assez largement partagée par les multiples héritiers du communisme, du gauchisme et du tiers-mondisme. D’autant plus qu’elle se veut – spécificité nauséeuse – un rejet de la discrimination. L’antijuif de notre temps ne s’affirme plus raciste, il dénonce au contraire le racisme comme il condamne l’islamophobie et, en stigmatisant les sionistes en tant que racistes, il s’affirme antiraciste et propalestinien. Les antijuifs ont retrouvé le chemin de la bonne conscience. (…) Autrefois rejetés comme venus d’Orient puis comme apatrides, les juifs sont à présent “désémitisés”, fustigés comme sionistes et occidentaux. L’antisémitisme refusait la présence des juifs au sein de la nation; l’antisionisme leur dénie le droit d’en constituer une. La rhétorique a changé. L’anathème demeure. Atila Ozer

Les juifs ont toujours été l’objet des calomnies d’une Europe ambivalente- montrés du doigt pour le trop grand exclusivisme de leur foi, ne disposant ni des lignées ancestrales des propriétaires terriens ni du statut des aristocrates. Les juifs commencent maintenant à se sentir aussi indésirables en Europe que dans les années 30 – ou qu’en 1543, quand Martin Luther écrivait sa diatribe« Des juifs et leurs mensonges ». Des universitaires juifs sont parfois tenus à l’écart dans les conférences internationales en Europe. Certaines banlieues de Paris et de Rotterdam ne sont plus sûres pour les juifs. L’Europe est en grande partie anti-Israël et le sera probablement toujours. Victor Davis Hanson (20.12.2011)

Le Père Noël a été sacrifié en holocauste. A la vérité le mensonge ne peut réveiller le sentiment religieux chez l’enfant et n’est en aucune façon une méthode d’éducation. Cathédrale de Dijon (communiqué de presse aux journaux, le 24 décembre 1951)

Il est généralement admis par les historiens des religions et par les folkloristes que l’origine lointaine du Père Noël se trouve dans cet Abbé de Liesse, Abbas Stultorum, Abbé de la Malgouverné qui traduit exactement l’anglais Lord of Misrule, tous personnages qui sont, pour une durée déterminée, rois de Noël et en qui on reconnaît les héritiers du roi des Saturnales de l’époque romaine » : dans l’Europe du Moyen-âge il était en effet de coutume à noël que les jeunes élisent leur « abbé », présidant à toutes sortes de comportements transgressifs mais provisoirement tolérés (filiation manifeste du roi des Saturnales romaines), et Lévi-Strauss voit dans cette élection réelle une généalogie du personnage mythique, devenu vieillard bienveillant (« l’héritier, en même temps que l’antithèse » (…) Grâce à l’autodafé de Dijon, voici donc le héros reconstitué avec tous ses caractères, et ce n’est pas le moindre paradoxe de cette singulière affaire qu’en voulant mettre fin au Père Noël, les ecclésiastiques dijonnais n’aient fait que restaurer dans sa plénitude, après une éclipse de quelques millénaires, une figure rituelle dont ils se sont ainsi chargés, sous prétexte de la détruire, de prouver eux-mêmes la pérennité. Claude Lévi-Strauss

Comme ces rites qu’on avait cru noyés dans l’oubli et qui finissent par refaire surface, on pourrait dire que le temps de Noël, après des siècles d’endoctrinement chrétien, vit aujourd’hui le retour des saturnales. André Burguière

Le XIX siècle a transformé Noël en une célébration de la famille bourgeoise. Il a du même coup installé l’enfant au centre du rite profane en lui attribuant un nouveau rôle, celui-ci étant révélateur du changement de son statut social et familial. D’acteur principal du rituel mettant l’adulte au défi, il est en effet devenu en un siècle et demi le récipiendaire d’un don infini et sans réciprocité. Martyne Perrot

Les islamistes – des musulmans déterminés à revenir à un code de lois médiéval – méprisent toute fête non approuvée par l’islam. Cette attitude archaïque et sectaire fournit le contexte du massacre du Nouvel An à la Nouvelle-Orléans qui a fait 14 morts et des dizaines de blessés. Les théologiens musulmans du Moyen Âge en ont exposé l’approche générale. Ibn Taymiya (1263-1328) affirmait que le fait de se joindre à des non-musulmans pour célébrer leurs fêtes équivalait à « accepter l’infidélité ». Son étudiant Ibn al-Qayyim (1292-1350) précisait que féliciter des non-musulmans à l’occasion de leurs fêtes « est un péché plus grave que de les féliciter d’avoir bu du vin, d’avoir eu des relations sexuelles illégales, etc. » De toutes les fêtes religieuses, Noël est la fête la plus détestée par les autorités islamiques car les chrétiens croient que Dieu s’est fait homme. Comme l’a observé l’historien Raymond Ibrahim, ces théologiens, qui croient que le polythéisme est le péché suprême selon l’islam, considèrent Noël comme « le plus grand crime jamais commis par l’humanité ». Les autorités modernes font écho à ces interprétations médiévales. Yousuf al-Qaradhawi, un chef spirituel des Frères musulmans, a déclaré que célébrer Noël équivalait à « abandonner l’identité musulmane » de la nation islamique. Le professeur saoudien Fawzan al-Fawzan a qualifié le tsunami du 26 décembre 2004 dans l’océan Indien de « punition d’Allah ». Il a déclaré : « Cela s’est produit à Noël, lorsque des fornicateurs et des personnes corrompues du monde entier viennent commettre la fornication et la perversion sexuelle. » En 2019, un ancien responsable de Qatar Charity, qui se décrit comme « l’une des plus grandes organisations humanitaires et de développement au monde », a informé les musulmans que Noël et le Nouvel An « contrevenaient tous deux à la charia d’Allah ». Il a ajouté qu’« il ne faut ni y participer ni coopérer avec les personnes qui les célèbrent », car « participer à leurs célébrations équivaut à prendre part à un crime et à une agression contre notre religion ». Les dirigeants islamistes en Occident régurgitent ces déclarations. L’imam français Younes Laaboudi Laghzawi juge qu’il est « interdit de célébrer Noël ou le Nouvel An. » L’imam canadien Younus Kathrada soutient qu’une personne qui demande des intérêts, qui ment, qui se livre à l’adultère ou à des meurtres n’a « rien fait de comparable au péché consistant à féliciter et saluer les non-musulmans lors de leurs fausses fêtes. » Dans l’ensemble, ces dirigeants ont légitimé la violence islamiste contre les non-musulmans pendant leurs fêtes. La violence peut être symbolique. En 2016, un groupe d’islamistes en Turquie a mis un pistolet sur la tempe d’un homme déguisé en Père Noël, expliquant qu’ils voulaient encourager « les gens à revenir à leurs racines ». Néanmoins, la violence peut également être réelle comme on a pu le voir ces 11 dernières années : Le 22 décembre 2014, un attentat sur le marché de Noël de Nantes, en France, a fait un mort et 9 blessés. Le 2 décembre 2015, un attentat lors d’une fête de Noël à San Bernardino, en Californie, a tué 14 personnes et en a blessé 22 autres. Le 14 juillet 2016, jour commémorant la Prise de la Bastille, un attentat perpétré à Nice, en France, a fait 86 morts et 434 blessés. Le 19 décembre 2016, un attentat sur le marché de Noël de Berlin a fait 12 morts et 48 blessés. Le Jour de l’An 2017, un attentat à Istanbul a tué 39 personnes et en a blessé 69 autres. le 31 octobre 2017, jour d’Halloween, un attentat à New York a tué 8 personnes et en a blessé 13 autres. Le 11 décembre 2018, un attentat sur un marché de Noël à Strasbourg, en France, a fait cinq morts et 11 blessés. Le 20 décembre 2024, un attentat sur le marché de Noël de Magdebourg, en Allemagne, a tué cinq personnes et en a blessé plus de 200 autres. Le 25 décembre 2024, un attentat commis à Lahore, au Pakistan, lors d’une célébration de Noël, a fait trois blessés, soit une semaine avant les violences plus graves encore à la Nouvelle-Orléans. (…) étant donné l’origine étrangère de la plupart des auteurs, les gouvernements occidentaux sont coupables non seulement de ne pas avoir réussi à arrêter l’immigration illégale, mais aussi d’avoir ouvert de manière irresponsable les vannes à l’immigration islamiste légale. (…) les Occidentaux ont tendance à s’inquiéter de l’islamisme au lendemain d’un acte de violence djihadiste, pour l’ignorer ensuite jusqu’au prochain accès de violence. Ne pouvons-nous pas garder à l’esprit cette menace civilisationnelle même lorsque les couteaux, les fusils et les bombes ne sont pas utilisés ? Cette attitude est essentielle pour pouvoir prendre des mesures cohérentes et efficaces contre l’idéologie totalitaire qui, actuellement, est la plus dynamique. Daniel Pipes

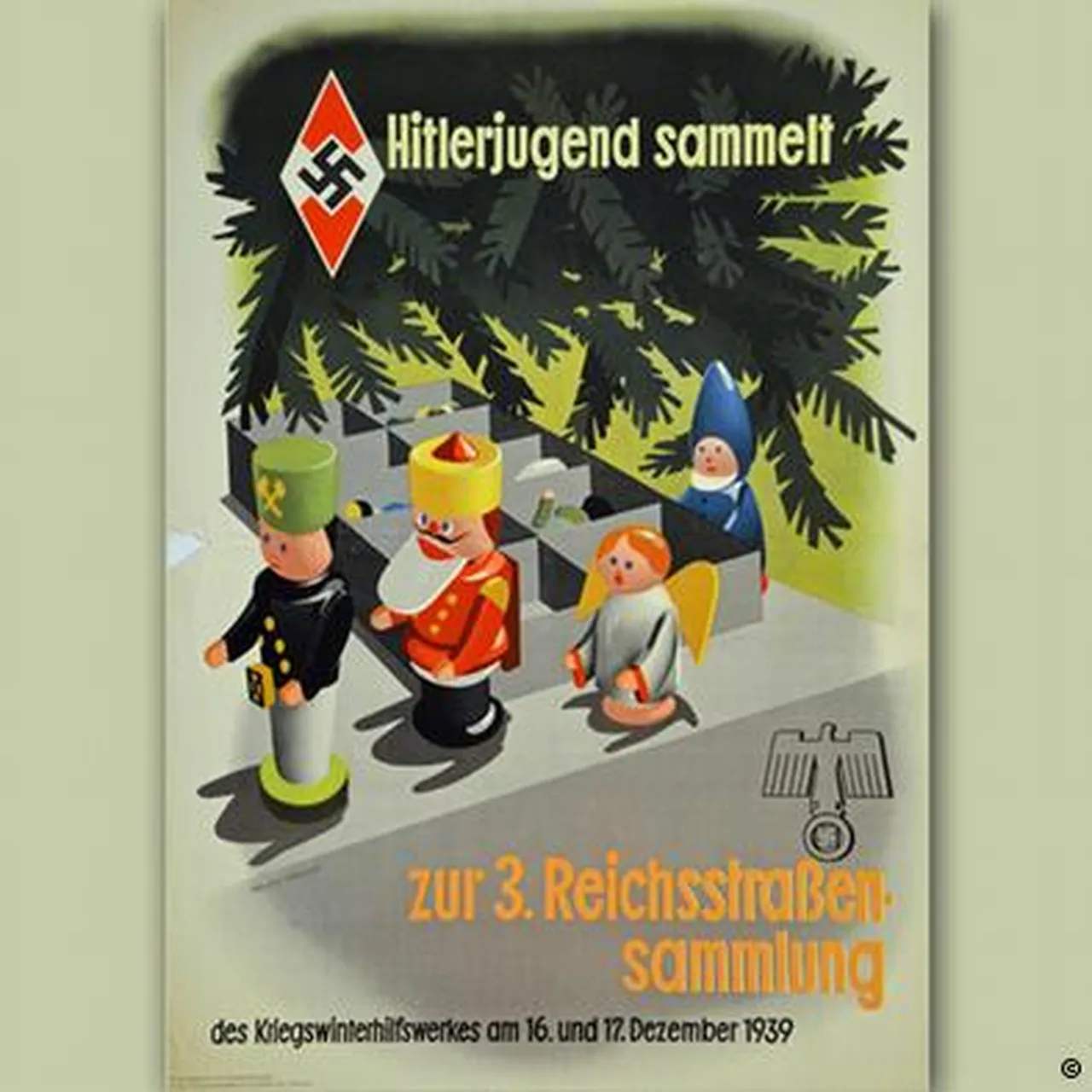

Saviez-vous qu’il existe un lien entre les Nazis et nos chers marchés de Noël ? Avec la dictature nazie, Noël devient une fête nationaliste. Les marchés de Noël permettront de promouvoir l’héritage allemand. A cette époque, la crise économique fait rage. Pour les nazis, les marchés de Noël permettent alors de stimuler stimuler l’économie avec des produits made in Allemagne. La France est le deuxième pas avec le plus de marchés de Noël. France info (instagram)

Nous avons publié une vidéo sur les marchés de Noël. Le titre était un raccourci. Nous choisissons de la retirer. France info

Oui, les nazis ont tenté d’instrumentaliser comme ils ont tout instrumentalisé mais réduire nos marchés à cet épisode minuscule, revient à occulter l’essentiel, une tradition, enracinée, joyeuse profondément européenne et d’origine chrétienne que certains cherchent aujourd’hui à effacer ou à salir pour créer une culpabilité identitaire artificielle, pourquoi, certains médias comme FranceInfo préfère t il déformer les symboles plutôt que de raconter ce qu’ils révèlent de notre histoire profonde. Christine Kelly

Franceinfo a raison : nos marchés de Noël ont bien un lien avec les nazis ! N’en déplaise à l’extrême droite qui souhaite réécrire l’histoire en attaquant au passage le service public. (…) Les marchés de Noël sont apparus en Europe au Moyen-âge. Ils se sont ensuite développés au XIXe siècle lors de la Révolution industrielle, mais sont relégués en périphérie des villes pour ne pas faire d’ombre aux grands magasins. En Allemagne, le phénomène des marchés de Noël revient en centre-ville durant le Troisième Reich. En effet, lorsque Adolf Hitler arrive au pouvoir, il fait de Noël une fête nationaliste. Et ce fait est largement documenté. Dans son livre « Christmas in Germany – a Cultural history », l’historien Joe Perry, professeur d’histoire aux Etats-Unis, cite l’exemple de Nuremberg. Le maire nazi de l’époque, Willy Liebel a fait revenir le marché en centre-ville en 1933, dans le but d’effacer ce qu’il appelait les « influences non allemandes et de races étrangères » qui avaient mené à la délocalisation du marché. L’objectif d’Hitler est de valoriser l’héritage allemand plutôt qu’une fête religieuse. Les marchés de Noël permettent donc de développer une tradition populaire et de dynamiser les ventes de produits fabriqués en Allemagne. Une nouvelle fois l’extrême-droite fait sa réécriture de l’histoire et attaque le service public au passage. L’Humanité

L’histoire étonnamment sordide des marchés de Noël allemands Depuis leurs origines médiévales et leur passage sous le régime nazi (…) Les propriétaires des nouveaux grands magasins du centre-ville ont fait campagne pour les faire déplacer afin d’éviter la concurrence. De Berlin à Nuremberg, les villes ont déplacé leurs marchés de Noël vers la périphérie, où ils ont langui pendant des décennies. (…) Dans les années 1930, les marchés de Noël ont fait leur retour dans les centres-villes allemands, avec l’aide du parti nazi. (…) Les dirigeants nazis pensaient que la vente de produits fabriqués en Allemagne pourrait contribuer à stimuler l’économie (…) Et cela a fonctionné. À Berlin, 1,5 million de personnes ont visité le marché en 1934, un record battu deux ans plus tard lorsque deux millions de personnes s’y sont rendues. (…) À l’époque, Noël était un enjeu politique, les politiciens s’efforçant de remodeler ses traditions pour les adapter à leurs tendances anticapitalistes ou athées. Amy McKeever (National Geographic)

Les Nazis (…) n’ont pas tardé à transformer Noël, fête religieuse consacrée à la paix sur Terre, en une fête nationaliste célébrant l’héritage allemand. (…) Noël a été complètement réinventé comme une ancienne fête païenne. (…) Le Père Noël a dû disparaître. (…) Les étoiles ont été interdites et remplacées (…) pour des raisons évidentes. (…) Noël dans les camps était d’une brutalité inimaginable. DB Kelly (Grunge)

Le marché de Noël perdait de son charme, et les réformateurs urbains, les intérêts commerciaux du commerce de détail et les autorités municipales regardaient avec inquiétude la croissance de la sous-classe urbaine qui se pressait dans le centre-ville pendant la saison des fêtes. Dès les années 1870, les élites civiques n’accueillaient plus favorablement l’atmosphère carnavalesque du marché. Le nombre de marchands volants avait augmenté ; contrairement aux vendeurs réguliers, qui payaient honnêtement leurs droits de vente, des centaines de mendiants sans licence, d’invalides de guerre, de gamins des rues et de chômeurs accostaient agressivement les visiteurs du marché. Les vendeurs officiels contribuaient également à l’atmosphère louche du marché, en proposant des attractions comme le Tingel-Tangel et en installant des Rummelplätze, ou des fêtes foraines, avec des manèges et des jeux de hasard. Les foules indisciplinées renversaient les hiérarchies de classe, minaent le spectacle sentimental du marché de Noël et menaçaient les profits des classes moyennes urbaines. (…) Rudolph Hertzog, propriétaire de l’un des premiers grands magasins de Berlin sur la Breitestrasse, s’est plaint à plusieurs reprises auprès des autorités du « caractère tumultueux » du marché de Noël, affirmant qu’il empêchait les clients aisés de faire leurs achats dans son magasin pendant la saison des fêtes. En 1873, alors que l’économie allemande s’effondre, les autorités municipales réagissent. Elles ferment la Breitestrasse, qui avait longtemps été le centre du marché berlinois, et limitent les festivités au Lustgarten voisin. (…) Les sociaux-démocrates se sont plaints amèrement que les habitants pauvres de la ville tiraient une part substantielle de leurs revenus annuels de la foire, et les projets de relocalisation vers d’autres quartiers du centre-ville échouent lorsque les résidents aisés du coin se plaigent de troubles potentiels. Finalement, en 1893, le chef de la police déplace le marché vers l’Akrona Platz, situé au milieu d’un quartier ouvrier, à ce qui était alors la bordure nord-est de la ville. (…) Communistes et nazis se sont approprié Noël comme symbole du déclin de la nation mais aussi de son potentiel, moquant parfois les observances sentimentales dominantes et déplorant parfois l’effondrement de la fête « allemande ». À aucun moment la « bataille pour Noël » dans l’Allemagne moderne n’a été plus publique et plus virulente que dans les dernières années de la République de Weimar. La gauche avait déjà soumis la fête à une déconstruction radicale sous l’époque wilhelmienne, et l’avant-garde continuait de se moquer des célébrations bourgeoises ; pensez seulement à l’Ange prussien porcin de John Heartfield, installé à la Première Foire internationale dada en 1920 et orné d’une bannière reprenant des vers du célèbre cantique de Luther « Vom Himmel hoch », ou à son Arbre de Noël allemand, dont les branches étaient tordues en forme de svastika. Les intellectuels communistes et leurs compagnons de route attaquaient les valeurs et symboles clés de la fête pour manifester leur mépris envers la culture de consommation moderne, la religion organisée et les valeurs bourgeoises en général. Des poèmes et récits de Noël au ton incisif de Kurt Tucholsky, Bertolt Brecht, Erich Mühsam, Erich Weinert et Erich Kästner mettaient en lumière l’appauvrissement, le chômage et la politique chauvine masqués par le sentimentalisme de la classe moyenne. Des parodies anonymes de cantiques d’église tels que « Douce nuit », « Ô combien joyeusement », « Du haut du ciel » et bien d’autres actualisaient la culture alternative sociale-démocrate de l’époque impériale. Les paroles de l’époque de Weimar avaient une dureté tranchante. La chanson anti-Noël d’Erich Kästner de la fin des années 1920, exemple typique, satirisaient les fantasmes consuméristes d’un cantique populaire avec des vers comme « demain le Père Noël vient, mais seulement chez les voisins » et « demain les enfants vous n’aurez rien ». Le KPD a mené une critique virulente de Noël dans les dernières années de Weimar. Contrairement à leurs concurrents sociaux-démocrates, qui marchaient sur une ligne délicate entre le rejet des abus capitalistes et l’appropriation de la fête conventionnelle, les communistes évitaient les alternatives « prolétariennes » et appelaient même à l’abolition pure et simple de la fête. Les propagandistes communistes attaquaient l’ « opium clérical » répandu par l’Église et l’État pendant les fêtes, exigeant qu’un appel aux armes remplace le son hypocrite des cloches d’église sonnées par l’ « ennemi de classe ». (…) Les conflits violents du réveillon de Noël témoignent de la brutalisation générale de la société de Weimar au début des années 1930 ; ils montrent aussi que Noël allemand était devenu un symbole émotionnellement chargé et politiquement contesté de la prospérité nationale. Au final, la version nationale-socialiste de Noël est apparue ironiquement comme résolvant les tensions que les Nazis eux-mêmes avaient largement provoquées. Contrairement aux protestations communistes anti-Noël ou aux platitudes bourgeoises, le Noël nazi envisageait un avenir national fier fondé sur un passé ethnique inventé. Sa rhétorique et ses rituels promettaient de guérir la communauté nationale avec des mythologies du « sang et sol », une reprise économique et l’exclusion raciale. (…) Les idéologues nationaux-socialistes comme la Dr Auguste Reber-Gruber, directrice de la section féminine du syndicat des enseignants nationaux-socialistes, étaient parfaitement conscientes que l’imagerie familière des sapins illuminés, des paysages enneigés et de la régénération faisait de Noël un puissant vecteur pour naturaliser une culture politique radicale enracinée dans un passé national mythique. Tout comme les Jacobins français et les bolcheviks russes avaient transformé leurs cultures festives pour tenter de former de nouveaux citoyens révolutionnaires, les nationaux-socialistes ont redessiné les fêtes allemandes pour les conformer aux agendas raciaux et idéologiques de l’État. L’intelligentsia nazie croyait clairement que les rituels familiaux autour du sapin de Noël engendraient un surplus émotionnel qui pouvait être manipulé pour construire et maintenir un sentiment national et un « moi fasciste ». (…) Dès le début, la liturgie chrétienne, les symboles et les sentiments ont séduit les nazis qui cherchaient à s’approprier les rituels religieux et familiaux. La version déchristianisée de Noël de Reber-Gruber, basée sur « le mythe du sang et l’ordre divin de la procréation éternelle » — sa tentative, en somme, de remplacer la naissance du Christ par celle d’un enfant « aryen » archétypal — révélait le glissement constant entre piété et politique, race et religion, rituel chrétien et rite païen qui définissait la célébration nazie. Empruntant à leurs adversaires sociaux-démocrates, les propagandistes nazis présentaient Noël et le solstice d’hiver comme une métaphore de la renaissance de la nation allemande. Selon les auteurs nazis, la célébration familiale préservait l’ethos des païens, quand « le sentiment d’unité avec le sol natal et la nature était encore vivant, le désir de lumière et de force avait de fortes racines, [et] les festivités de Yule restaient une manifestation sacrée de Dieu ». La récupération des rites nordiques mythiques n’excluait nullement les appels aux aspects chrétiens de la fête. (…) La fête révisée promue par les Chrétiens allemands illustre le conflit religieux et politique au cœur de Noël dans les années nazies. Leurs tentatives d’inventer une fête « racialement correcte », comme le suggère l’historienne Doris Bergen, exprimaient un effort déterminé mais paradoxal et souvent nocif pour synthétiser christianisme et national-socialisme. La doctrine des Chrétiens allemands combinait l’idéologie nazie avec des traditions chrétiennes réformées et déjudaïsées qui présentaient la nation, le Volk et la race comme des dons de Dieu. (…) Pour Bauer et d’autres Chrétiens allemands, la « vérité de Dieu » signifiait la « germanisation du christianisme », un processus supposément commencé par Luther. Pour poursuivre ce travail, l’Église devait purger les influences judaïques de la théologie et des textes chrétiens, supprimer les psaumes « juifs » de la Bible et remplacer les noms et termes « juifs » dans les prières et les hymnes par des équivalents germano-nordiques. (…) Des groupes politiques concurrents, y compris les nazis et les communistes, les libéraux et les sociaux-démocrates, ont tous façonné leurs propres versions de la fête. Chacun tentait de manipuler les émotions intimes évoquées par la célébration familiale pour soutenir leurs différents programmes politiques. Joe Perry (Noël en Allemagne – une histoire culturelle, 2010)

Nazifiez, nazifiez, il en restera bien quelque chose !

Devinez pourquoi deux ans avant une présidentielle critique qui devrait logiquement voir l’arrivée au pouvoir du premier parti de France …

Et au moment où certains de nos marchés de Noël sont bunkérisés ou fermés entre les imprécations des bouffeurs de curé, les actions en justice au nom de la laïcité, les appels à la décroissance des écologistes et les bombes et voitures-béliers des islamistes …

Notre service public, soutenu par ses compagnons de route de l’Humanité, fait feu de tout bois pour tenter de rediaboliser, en décontextualisant des éléments historiquement attestés, jusqu’à notre fête de Noël…

Reprenant derrière un titre aussi aguicheur que réducteur à l’instar des vidéos de vulgarisation historique des maitres-piégeurs à clics à la National Geographic ou Grunge qui pullulent sur l’internet …

Le fait historique, mais dramatisé et décontextualisé, qu’Hitler et les nazis ont effectivement contribué, au moins dans certaines villes comme Berlin ou leur ville-fétiche de Nuremberg …

Au retour ou au renforcement dans les centres-villes des marchés de Noël en plein air…

A une époque où après les années de déconstruction sous la République de Weimar de l’avant-garde dada et des marxistes dont le parti communiste allemand…

Ils étaient à nouveau menacés à la fois par la commercialisation des grands magasins …

L’opposition de certains socialistes et communistes qui voulaient les interdire en tant qu’opium du peuple …

Et les dirigeants chrétiens et les fidèles inquiets de leur marchandisation …

Sans parler des élites urbaines et de la police, irritées par certains de leurs aspects les plus sordides, car ils attiraient également la racaille et les masses indisciplinées …

Sauf que cela faisait partie, s’appuyant sur les derniers écrits résolument antisémites de Luther lui-même, d’une tentative (qui dura quand même 12 ans), à laquelle eux aussi ont finalement renoncé face à la résistance du peuple…

De re-germaniser et de déjudaïser la religion chrétienne elle-même !

The surprisingly sordid history of Germany’s Christmas markets

From their medieval roots and their brush with Nazis, these beloved bazaars are now celebrated around the world

Amy McKeever

National Geographic

December 19, 2022

Every holiday season, Christmas markets transform the main squares of cities across Europe into winter wonderlands. Twinkling lights adorn wooden huts and boughs of holly hang from street lamps. Vendors sell hand-carved ornaments and Nativity scene figurines, alongside piping hot mugs of glühwein (mulled wine), as Christmas carols fill the air. In Germany alone—where the tradition began—there are usually 2,500 to 3,000 holiday markets a year. Now, the markets are returning after two years of COVID-19 related closures.

Historians say preserving this cultural practice in old city centers is as important as shoring up medieval cathedrals or protecting ancient Roman ruins. They argue that Germany’s markets should be inscribed on UNESCO’s intangible cultural heritage list, alongside French baguette making and dragon boat festivals in China.

“What makes [the markets] so important isn’t just buying an ornament,” says Dirk Spennemann, associate professor in cultural heritage management at Australia’s Charles Sturt University, who has co-written studies about the cultural heritage of Christmas markets. “It’s this whole experience of sound, smell, visuals, but also the physicality of people around you.” What’s more, Spennemann argues that “intangible cultural heritage” encompasses traditions that are meant to be mutable, reshaped with each new generation.

Christmas markets certainly fit that definition. Over their centuries-long history, they have adapted to the changing politics and social customs of each new era—from the industrial revolution to the rise of the Nazi party.

Early Christmas markets

Europe’s Christmas markets date back to medieval times when German territories covered a wide swath of the continent. Some of Germany’s existing Christmas markets trace their origins as far back as the 15th and 16th centuries. Dresden’s market first opened for one day on Christmas Eve in 1434. Meanwhile, the oldest evidence of Nuremberg’s Christmas market dates it to 1628, though some suspect it stretches back at least to 1530.

Spennemann says it’s unclear, however, whether these early bazaars were held for Christmas or simply took place at Christmastime. Back then, people lived in scattered communities within walking distance of a church that held markets for all religious feast days. The winter market was typically the biggest, with local artisans selling pottery, meat, baked goods, and maybe some sweets, if the sugar wasn’t too expensive.

There’s little record of the atmosphere of those early markets or when they shifted to offer Christmas trees, Nativity scenes, and toys. Some illustrations depict wealthy Germans hobnobbing in the main market square, while the poor shopped at back-street stalls. But Spennemann says these images are likely embellishments created by artists of later eras, who yearned for what was—to them—an idyllic Christmas past with each social class in its plac

The Industrial Revolution had a profound effect on Christmas markets in the early 19th century. The rising standard of living and the emergence of the working class fueled the growth of Christmas markets. In Berlin, for example, the Christmas market grew from 303 stalls in 1805 to about 600 in 1840.

As the markets began to cater to the working class, urban elites turned up their noses at the cheap gifts for sale, while police in cities across Germany complained about the unruly masses of workers who frequented them.

“It was seen as being seedy, even dangerous and threatening,” says Joe Perry, associate professor of modern European and German history at Georgia State University and author of Christmas in Germany: A Cultural History.

Capitalist forces also turned against the markets by the end of the 19th century. The owners of new downtown department stores campaigned to have them moved to avoid competition. From Berlin to Nuremberg, cities relocated their Christmas markets to the outskirts, where they would languish for decades.

Nazis reimagine the Christmas markets

In the 1930s, Christmas markets returned to city centers across Germany—with the aid of the Nazi Party.

Christmas was a political football at the time, with politicians endeavoring to reshape its traditions to fit their anti-capitalist or atheist leanings. When Adolf Hitler became chancellor in 1933, his newly empowered political party wasted no time in transforming Christmas from a religious holiday devoted to peace on Earth to a nationalist one that extolled German heritage. As Erin Blakemore writes for History magazine, party officials inserted Nazi imagery into Nativity scenes, filled Advent calendars with party propaganda, and rewrote Christmas carols like “Silent Night” to deemphasize its Christian connotations.

These efforts weren’t unprecedented. Perry points out that the idea of a culturally German Christmas has “deep, deep roots.” Many traditions, from Advent calendars to Christmas trees, are thought to have originated in Germany. Protestant reformer Martin Luther is often credited with being the first to put lights on the Christmas tree, after a nighttime stroll through a German forest under a starry sky.

Christmas markets were a natural fit in the effort to realign Christmas with Nazi ideology because they were a popular tradition that already existed. In Nuremberg, for example, Nazi mayor Willy Liebel moved the market back to the city center in 1933, as “a way to erase what he called the ‘un-German and race-alien influences’ that had inspired the market’s relocation,” Perry writes in his book.

The market also debuted an opening ceremony featuring the

Soon after, Nazi politicians began to standardize stall decorations and the items that vendors could sell—such as German-made ornaments, toys, handicrafts, bratwurst, and sugary confections.

Economics drove part of these efforts to rejuvenate the markets, says Perry. In the midst of the Great Depression, Nazi leaders believed the sales of German-made goods could help stimulate the economy and raise the spirits of German citizens.

And it did. In Berlin, 1.5 million people visited the market in 1934, a record broken two years later when two million people visited. But that economic prosperity ended with the start of World War II. In 1941, many cities shuttered their markets.

A post-war Christmas market boom

Germany’s Christmas markets came roaring back after the end of the war—and only grew in the following decades, as an economic boom in the 1960s and 1970s and the rise of consumerism fueled the growth of Christmas shopping. These economic shifts transformed the Christmas markets into mass cultural events—up to a thousand tour buses full of shoppers might descend on a city’s Christmas market during any given weekend.

The Nazi’s role in reshaping the Christmas markets was largely swept under the rug, even as

While some Germans sought to trivialize the Nazis’ role in shaping the Christmas markets, Perry points out that other German political parties through the years have sought to influence the tradition. In the early 20th century, Marxists tried to reframe Christmas as a pagan rather than a religious holiday. Later, the Communist Party in East Berlin would also attempt to align Christmas with its values. Christmas “has always been pushed and pulled around,” he adds.

Germany’s intangible cultural heritage

In Germany, meanwhile, the number of Christmas markets has also been on the rise for the last 50 years—tripling from about 950 markets in the 1970s to about 3,000 in 2019. Local tourism bureaus use them to persuade people to visit during winter’s bleakest days, and tour companies have expanded from bus tours to Christmas market river cruises that stop in cities along the Danube, from Germany to Hungary.

“Clearly substitutions don’t work,” Spennemann says. “Unless you go and give people the virtual 3D experience and send them a vial of smells, it’s not going to work.”

By documenting the history of the Christmas markets, the scholars hope to lay the groundwork should Germany decide to apply for UNESCO recognition. But Spennemann says that safeguarding the markets doesn’t mean keeping them from changing—it’s to keep them alive through change.

Some people, he says, insist that traditional German culture must involve wearing lederhosen and drinking from steins, but “they deep-freeze culture, and they ritualize it, and they kill it. Intangible culture is a vibrant expression which will change. So you have to allow for that change.”

In fact, he argues that intangible cultural traditions like the Christmas markets are so meaningful because they have evolved to represent who we are at any given time—for the better and, yes, sometimes for worse.

Christmas markets move beyond Germany

By the 1980s and 1990s, Germany’s Christmas markets had become so beloved that they became a cultural export. Cities in countries around the world—including the United States, Japan, and India—began to host their own German-style Christmas markets, complete with bratwurst, glühwein, and twinkling lights. In the United Kingdom, the number of Christmas markets more than tripled from about 30 in 2007 to more than a hundred in 2017.

Some of the most bustling markets around the world, now back in merry force, include the Edinburgh Christmas Market, which offers drams of whisky, a Ferris wheel, and artisan stalls in the Scottish capital. Plaisirs D’Hiver (Winter Pleasures) clusters around a towering decorated spruce in the center of Brussels, Belgium, and includes chocolate sellers, live music, and a light-and-sound show. In New York City, the Union Square Holiday Market brings together nearly 200 local vendors from pottery makers and jewelry designers to hot cocoa mixers and poutine chefs.

How The Nazi Ideology Ruined And Reshaped Christmas

DB Kelly

Grunge

Feb. 12, 2022

If there’s any nation in the world that’s most in love with Christmas, it’s Germany. So many of the Western world’s Christmas traditions come from Germany, it’s pretty mind-blowing. It’s where the idea of the Christmas tree started, and according to The German Way and More, they were also the ones who started making the first ornaments. That was way back in the 16th century, when glassblowers created stunning decorations that today’s mass-produced ornaments can’t hold a candle to.

Those open-air Christmas markets that are so much fun, especially with a steaming cup of mulled wine spiked with brandy or rum? Yep: German. The Guardian says the first Christkindlmarkt was held in 1384. Oh, and that drink? The Romans may have first made mulled wine, but it was the Germans who made it Gluhwein and hailed it for supposedly curative powers (via The Kitchn). So, it’s safe to say that Germany loves Christmas.

Well, most of Germany.

It was the Nazis who had a major problem with Christmas, and it’s easy to see why they wouldn’t be down with the entire country spending a month celebrating the birthday of a Jewish man. But Christmas was such a part of the nation’s cultural landscape that banning it altogether just wasn’t going to work. What’s a Fuhrer to do? Co-opt it, give it an overhaul, and try to make it into something completely different.

Why Hitler hated Christmas

Print Collector/Getty Images

Joe Perry is a Georgia State University history professor, and he says (via The Conversation) that Adolf Hitler started hating on Christmas really, really early on in his career, and some of his early statements are sort of surprising.

It was around Christmastime of 1921 that he gave a speech in Munich, and it was very foreshadow-y, to say the least. While overlooking a major part of Jesus’s story (remember, he was not only Jewish, but the scholar Jaroslav Pelikan points out — via PBS — that in several places in the scriptures he’s given the title of « Rabbi »), Hitler made it very clear that Jews were the villains of Christmas. He shouted about « the cowardly Jews for breaking the world-liberator on the cross, » and he kind of set the stage for his plans about the Holocaust. It was in regard to Christmas that he promised « not to rest until the Jews … lay shattered on the ground, » and this was more than a decade before he was installed in a position of real power.

But there was more to it. Hitler, says Fast Company, also hated the idea that Christmas promoted peace — and it extended to everyone. That’s pretty much the exact opposite of what Hitler had in mind for the future of Germany, so there was only one thing left to do: Remodel Christmas.

Nazis set themselves up as defenders of the holidayOne of the biggest questions that comes with the Nazis is, « How the heck did any of this happen? » That goes for their overhaul of Christmas, too, so it’s worth mentioning just how they set themselves up in a position to co-opt the nation’s most beloved holiday.

Gerry Bowler is the author of « Christmas in the Crosshairs, » and says (via the Oxford University Press) that there was a lot going on in Germany in the beginning of the 20th century. Christmas had become something to fight over. While the Communist Party condemned it for being the embodiment of both capitalism and religion, the Social Democrats had their own issues with it. They hated it because it put a very twinkly spotlight on the hypocrisy of well-to-do people who preached charity and good will, at the same time the poor struggled to put food on the table. It got so bad that there were calls to cancel Christmas all together, and that’s where Hitler’s National Socialists stepped in. « Oh, no, no! » they said. (We imagine.) « You can’t cancel Christmas, and we’re here to make sure that doesn’t happen! »

Hitler’s Sturmabteilung — the brownshirts — even took to the street to rough up anyone who was suggesting Christmas needed to be canceled. That escalated to the foundation of a welfare campaign that came around every Christmas, and by the time the Nazis really got to work, they were Christmas champions in the minds of many.

Julfest and Rauhnacht, the Rough Night

Wikipedia

Imgard Hunt grew up in Obersalzberg, and she lived under the shadow of Hitler’s alpine retreat. Her memoir, « On Hitler’s Mountain, » recounted what it was like to grow up in Nazi Germany, and one of the things she wrote about (via The New York Times) was how they tried to change Christmas.

At the heart of the co-opting was an attempt to de-Christianize Christmas and return it to the old ways. They wanted Christmas to return to something like it would have been in the pre-Christian, pagan era, and that means renaming it. The entire season became known as Julfest — or Yuletide — and folded into that was a celebration called Rauhnacht. That translates to the « Rough Night, » and it was a callback to an era that predated things like running water and gas heaters. People needed to be tough to survive the winters, and the traditions of Rauhnacht gave the holiday season a little bit of that hard edge back.

To be clear, Rauhnacht wasn’t a Nazi invention, they just really liked to promote it. Invest in Bavaria says it goes back to at least the 1720s, and it’s typically observed between the winter solstice and Epiphany (January 6). That’s when people performed ritual cleansings to rid their home of the evil spirits that were thought to roam the earth during these long nights, while others would don homemade — and horrible — masks to parade through the streets and send those spirits on their way.

Christmas got a complete re-branding as an old pagan holiday

Wikipedia

Every Christmas, there’s a debate: Is saying « Xmas » taking Christ out of Christmas? (No, says Vox: That « X » is sort of a shorthand for Jesus.) The Nazis, on the other hand, really did try to remove any and all mentions of Christ from the holiday. That, says DW, started with the rebranding of the holiday as Julfest, but it definitely didn’t end there. Instead of being all about the birth of Christ, Georgia State University history professor Joe Perry says (via The Conversation) that the Nazis tried turning the holiday into something that celebrated the origin story of the Aryan race instead.

It became a sort of neo-pagan celebration of the winter solstice and the return of the sun. They explained the overhaul by insisting that this was the way their people had done things when they were still « racially acceptable, » and before they were corrupted by modern religions. Gone was the idea of God and a divine being, and it was replaced with olde-timey rituals that focused more on lights, candles, and calling the sun back.

Not only was Christianity removed, but the Nazis also took the opportunity to turn the holiday into some antisemitic propaganda, too. Jewish businesses were boycotted, shops and catalogs boasted they were Aryan-owned, and the resulting message was very clear: Julfest was Aryan-only, and it celebrated Aryan roots.

Family was at the center of a Nazi Christmas

Beto Gomez/Shutterstock

Christmas is all about family, and for the Nazis, that was both true and different. The Nazis were all about families … as long as they were the right kind. According to The Guardian, families were also encouraged to celebrate Julfest together, and were sent gifts — like Julfest candles — to be used in the observance of the new, Nazi-fied holiday.

Georgia State University history professor Joe Perry says (via The Conversation) that images released to promote the new holiday had a few purposes. Not only was German media flooded with illustrations of blond-haired and blue-eyed families celebrating Julfest in the « proper » way in order to get families on board with that but adds that it was also used to further ideas about what the perfect family was. Women in particular were targeted, lauded as « protector of house and hearth, » and told that it was up to them to make sure their homes were properly Germanic.

In order to really get their point across, they co-opted something else, too. According to DW, Nativity scenes were changed from the traditional depiction of Mary and Joseph looking down at the little baby Jesus, and turned into blond-haired, blue-eyed parents and their blond-haired, blue-eyed baby, to better represent the Nazi ideal. The Nativity stayed, but it looked very, very different.

Writing and rewriting Christmas carols to Nazi standards

Africa Studio/Shutterstock

Christmas isn’t Christmas without the carols, and the Nazis had their hands in co-opting these, too. According to The Telegraph, it was Heinrich Himmler who was put in charge of rewriting carols into something more appropriate. That meant taking religious references out of all of them, and they did. « Unto Us a Time Has Come, » for example, was rewritten to remove mentions of Christ, and here’s the really shocking thing: The religion-free, Nazi version is the one that stuck, and it’s still sung today.

DW says that in other cases, entirely new carols were written — like « High Night of Bright Stars. » And yes, the Nazis went a few steps further, because of course they did: Barbara Kirschbaum of the National Socialism Documentation Center says: « The Nazis tried to ban some of the Christmas carols with open Christian content. »

And finally, in a « if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em » kind of way, Fast Company says that whenever the Savior was mentioned in a carol, the Nazis insisted that be replaced with « Savior Fuhrer. »

Santa had to go

Wikipedia

Santa is such a popular figure in Germany that there are a couple gift-giving old men that pop ’round during the holiday season. The one that’s associated with the Santa Claus of other countries is called Weihnachtsmann, and then there’s also St. Nikolaus, who shows up on December 6 and fills shoes with toys and coins. Similar, says The Local, but completely different people.

The Nazis found that Santa was so popular that while they could get rid of Christ, they had no chance of getting rid of the gift-giving figure of Father Christmas. What’s a Nazi to do? The answer, says Spiegel, was to claim that it wasn’t the Christian saint Nicholas of Myra who was dropping toys into shoes, it was the Norse god Odin.

Fast Company adds that the Nazis kind of doubled down on this one, too. They claimed that this was nothing new and it had always been Odin: Christianity had taken the ancient figure of Odin and assigned him the name and origin story of St. Nikolaus. The Nazis, it went, were just restoring things to the proper and original ways. Once again, they could market themselves as the defenders of the true holiday.

Stars were banned and replaced … for obvious reasons

Leon Neal/Getty & Chernousov family/Shutterstock

Stars have been an important part of Christmas decorations for a long, long time — the Star of Bethlehem appeared in the sky when Christ was born, after all. But according to Spiegel, that’s not why the Nazis felt the need to get rid of them. The star meant something else to the Nazis: With six points, it was the star of David used to identify the Jews, and with five points, it was the one won by the Soviet Army.

Fast Company says that the Nazis had a whole list of acceptable symbols to replace the star. When it came time to put something on the very top of the tree, they suggested a swastika — which were, incidentally, also popular for ornaments, allowing for a whole Nazi-themed tree. Other suggestions were the German sun wheel, which the Anti-Defamation League says was co-opted by the Nazis from Old Norse and Celtic mythology, and the lightning bolts of the SS. Those were plucked from a pre-Roman alphabet, and while they’re now associated with things like white supremacy and, of course, the Nazis, they were at one time called the sun rune, or sowilo.

Meanwhile, other decorations got replaced, too. Traditional cookie cutters were swapped for swastikas and sun wheels, while ornaments in the shape of grenades, guns, eagles, Iron Crosses, and even little Hitler figures were hung from trees.

Heinrich Himmler and the Yule Lantern

Keystone/Getty, Wikipedia

Just because the Nazis tried to remove both Christianity and Judaism from Christmas, that doesn’t mean it was religion-free. Anyone looking for unusual Christmas decorations to add to their holiday celebrations today can still buy the lantern called the Julleuchter, or Yule lantern. They’re essentially a kind of lantern or candlestick, and while their distinct design was inspired by earlier Nordic lanterns, NS Kunst says that the concept was purely the invention of Heinrich Himmler.

The purpose of the Julleuchter was described in Fritz Weitzel’s book « The Celebrations In The Life Of The SS Family. » According to the text, it was to be displayed prominently in an « SS-corner » of the home, which would include « all those things … which strengthen the voice of our blood and the duties to land and Folk, everything that demonstrates our beliefs. » While other things around the Julleuchter would change based on the season, the lantern would always be there.

Himmler wanted every member of the SS to have a Julleuchter specially gifted from him, and there were a lot made — by, says Spiegel, the prisoners at Dachau and Neuengamme. It’s unclear how many were produced and how many were used by their intended recipients, but they still have managed to hold on as a lasting reminder of the Nazi influence on the Christmas holiday.

How successful was it?

Wikipedia

Here’s the million-Reichsmark question: Did people buy into this new Nazi Christmas? Georgia State University history professor Joe Perry says (via The Conversation) that it’s hard to tell, but there are some documents that give us an idea of what the reaction was like, particularly among the women who were dubbed « priestesses » of this new holiday.

The National Socialist Women’s League (NSF) was, says UNC-Chapel Hill, the women’s corner of the Nazi Party. There were more than 2.3 million members as of 1933, and they brought some major pushback against the remodeled Christmas. Records speak of « much doubt and discontent » within the organization, while churches went very public with their condemnation of the Reich’s new winter holiday. Scores of women cited Julfest as their reason for not joining the NSF, and it probably didn’t hurt that in some places, their churches had made it quite clear that they would be excommunicated for joining.

That said, reports compiled by the Nazi’s secret police reported on how popular Julfest was. These were the families that wanted traditional celebrations reserved for the Aryan families, but still, there were plenty that still put that star on the top of their trees.

Christmas and Julfest as the war dragged on

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J28377 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

By 1944, pretty much everyone was sick of the war — and Nazi propaganda around the winter holiday actually reflected that. While much of the correspondence from early in the war involved things like how to make Nazi-fied cookies, Spiegel says that as the war dragged on into 1945, the Nazi powers-that-be tried to reinvent the holiday again, and make it a commemoration for the soldiers who had died protecting the homeland. Every year, holiday propaganda circulated — and that year, Traces of War says it included stories like the tale of a German man who only wanted to return to Germany to die.

A speech written by Thilo Scheller was published in « Die Neue Gemeinschaft, » or « The New Society. » It was supposed to be read out in military hospitals where German soldiers lay injured and dying, and reminded them that « our Fuhrer Adolf Hitler … will not forget those who cannot celebrate Christmas with their loved ones. » Every celebration, they wrote, should include « all our dead comrades from all the battlefields of Europe. »

Now, the holiday turned into a « cult of death, » with illustrations of decorated trees over graves marked by Iron Crosses. Official recommendations for celebrations included lighting candles for « the mother, the poor, the dead, and the Fuhrer, » setting a place at the dinner table for the dead men of the family, and lighting red candles in their memories.

Christmas in the camps was brutal beyond belief

Keystone/Getty Images

The Nazi party didn’t just have their official guidelines for how Christmas was going to be celebrated under the regime, the SS guards in charge of the concentration camps had their own ideas, too — and it was brutal. Auschwitz-Birkenau, for example, had a Christmas tree. It was set up in the area where roll call was taken every day, and that Christmas in 1940 was the Christmas when prisoners were greeted with a grisly sight: Piled beneath the tree in lieu of brightly wrapped packages were the corpses of the recently dead. The Memorial and Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau has collected testimonies of camp survivors, and it was Karol Swietorzecki who recalled the guards referring to the bodies as « a present. »

On Christmas Eve in 1941, around 300 Soviet POWs were killed in a holiday sacrifice, and that same year, prisoners were forced to stand outside in the freezing temperatures as they listened to Pop Pius XII’s Christmas speech. Dozens died where they fell.

The grisly Christmas tree was back in 1942, and in 1943, they were allowed actual gifts from their families. By 1944, it wasn’t about what the Nazis wanted anymore, not entirely. Primo Levi was a prisoner there for that Christmas, and later wrote (via Tablet), « At night, when all the noises of the Camp had died down, we heard the thunder of the artillery coming closer and closer. »

Liberation came just after New Year’s, on January 18.

Voir également:

Christmas in Germany: A Cultural History

Joe Perry

University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill

2010

Under the Sign of Kauflust (Chapter four)

/…/ During the decades bracketing the First World War, the arrival of mass culture and a new media landscape of daily newspapers and then radio and film altered conventional nineteenthcentury consumer practices. Commercialization appropriated popular traditions — like the annual outdoor Christmas markets set up in German towns and cities, or the family rituals practiced around the Christmas tree — and sold them back to the masses in new forms. Access to the goods and practices that inspired the Christmas mood was now more than ever tied to the ability to pay rather than the cultural capital of bourgeois social status. The commercialization of Christmas furthermore weakened familiar boundaries between public and private life. (…) The Christmas market was losing its charm, and urban reformers, retail business interests, and city authorities viewed with alarm the growing urban underclass that crowded into the city center during the holiday season. By the 1870s, civic elites no longer welcomed the carnivalesque atmosphere of the market. The number of flying dealers had increased; unlike the regular salespeople, who honestly paid their vendor fees, hundreds of unlicensed beggars, war invalids, street urchins, and unemployed people aggressively accosted market visitors. Official vendors also contributed to the seedy atmosphere of the market, offering attractions like Tingel-Tangel and setting up Rummelplätze, or midways, with rides and games of chance. Unruly crowds upended class hierarchies, undermined the sentimental spectacle of the Christmas market, and threatened the profits of the urban middle classes. Rudolph Hertzog, owner of one of Berlin’s first department stores on Breitestrasse, repeatedly complained to authorities about the “tumultuous character” of the Christmas market, which, he asserted, prevented well-heeled customers from shopping in his store during the holiday season. In 1873, as the bottom fell out of the German economy, city authorities responded. They closed off Breitestrasse, which had long been the center of the Berlin market, and limited festivities to the nearby Lustgarten. In contrast to other popular markets and street fairs, many of which disappeared altogether in the late nineteenth century, the Christmas market survived. Yet its “historic rights” and popular festive character did little to dampen criticism. The conflicts of interest climaxed around 1890, just as the department store emerged as an alternative site for shopping and sociability. In 1889 the Berlin chief of police reopened the campaign against the public market, complaining that the “nuisance-makers” in the Christmas market sold poor-quality “rummage.” The “inconsiderate pushiness of the poor” — just outside the Royal Palace at the head of the showcase avenue Unter den Linden — threatened the “good reputation” of the Reich’s capital city. The Berlin city magistrate’s office, to the contrary, took a sympathetic view of the street fair. The magistrate argued that the market’s “joyful mercantilism” gave the lower classes a chance to shop without the financial and social constraints imposed in exclusive department stores. A visit to the market in the city center gave working-class children a chance to at least see delightful displays of toys, “almost their only Christmas joy.” The chief of police replied that department-store show windows could provide the same solace. Social Democrats complained bitterly that impoverished city dwellers made a substantial portion of their annual income at the fair, and plans for relocation to other downtown districts faltered when wealthy local residents complained about potential disturbances. Finally, in 1893 the chief of police moved the market to Akrona Platz, located in the midst of a working-class district on what was then the northeastern edge of the city. There, it languished for the next forty years. “Only the meager remnants of the Christmas market in the east of the capital city still tempt the desires and the hopes of children,” wrote journalist Hans Ostwald in 1924. The Christmas market’s return to Breitestrasse and the Lustgarten in the Nazi years provides something of an uncomfortable coda to its nineteenthcentury decline. In December 1934 the city administration, in collaboration with the Arbeitsgemeinschaft zur Belebung der Berliner Innenstadt (Working Group for the Reinvigoration of Berlin’s Inner-City), moved the market back to the city center. Led by Karl Protze, a Berlin senator and National Socialist Party member, the Working Group convincingly asserted that “this wonderful German custom” breathed life into the Nazi slogan “Gemeinnutz geht vor Eigennutz” (Collective Need before Individual Greed). “For fifteen years,” the group noted in reference to socialist street demonstrations, “the Berlin Lustgarten has been a showplace for fanatical popular instigation and political strife.” Now the return of the Christmas market would turn this prominent public square into “a place of peaceful and friendly events.” The history of the famous Christkindlesmarkt in Nuremberg had a similar trajectory. Commercial interests had forced the market out of the central market square around the Church of Our Lady in 1898. In 1933 Nazi mayor Willy Liebel brought it back — a way to erase what he called the “un-German and race-alien influences” that had inspired the market’s relocation — and established a new opening ceremony. There was a time when the Christmas trade took place almost entirely in the outdoor booths set up for this purpose, from which it later moved for the most part to the increasingly numerous retail stores,” wrote a Berliner in 1889. “Now it seems that the critical hour [for these small businesses] is not far off. The so-called ‘department stores’ and giant outlets, which can buy large quantities of goods and sell them at cheap prices, increase their numbers from year to year, and are putting an end to the way shopping is done in the Christmas season, along with so many other traditional customs.” (…) An outdoor “Anti-Semitic Christmas Market” set up in Berlin in 1891 offered shoppers a way to avoid “Jewish” department stores altogether, but it apparently met with little success. (…) By the late 1920s, radio and newsreel reports on Christmas (portrayals of decorated city streets, famous German churches, Christmas markets, geese ready for table, choirs singing holiday carols) greeted Germans each holiday season.22 Enjoying some form of centralized mass entertainment was in and of itself a holiday ritual. Even before the arrival of the National Socialist “media dictatorship,” Christmas encouraged a growing audience to envision Germany as a “national audiovisual space.”23 In the 1930s, the mass media became increasingly important for the popularization of national self-identities refracted through leisure and holiday time, and a strikingly similar process was at work across Western societies. For Americans and other Europeans as well as Germans, this “most dramatic era of sound and sight” created novel sources of common experience for huge audiences. If the annual lighting of the “National Community Christmas Tree” in Washington, D.C., described in dramatic radio broadcasts in the 1920s and 1930s, embodied the democratic impulse behind Progressive-era reforms, in Nazi Germany the new media Christmas was shot through with fascist ideology.25 Christmas radio shows, by the 1930s a familiar aspect of private festivity, seamlessly blended propaganda and family entertainment. Father Christmas’s Radio Program, broadcast on Christmas Eve in 1937 (when all major German radio stations carried the official program), typified the genre. Those who tuned in at 8:00 p.m. that night heard a “Christmas message” from Rudolph Hess (the “Führer’s Deputy”); carols sung by a children’s choir; a show on Christmas festivities in the army, navy, and air force; and the sound of ringing bells broadcast from Germany’s most famous cathedrals.26 The audiovisualization of the German Volksgemeinschaft was repeatedly realized in radio broadcasts and newsreel shots of Christmas bells ringing in famous churches throughout Germany. Unlike Russian Bolsheviks, who, during the “Great Turn” (1928 to 1932) saw church bells as symbols of the “Old Way of Life” they wished to destroy, Nazi propagandists used modern media to colonize and exalt sacred practices. Communists and Nazis appropriated Christmas as a symbol of the nation’s decline but also its potential, at times mocking sentimental, mainstream observances and at times decrying the collapse of the “German” holiday. At no time was the “battle for Christmas” in modern Germany more public and vicious than in the closing years of the Weimar Republic. The left had already subjected the holiday to radical deconstruction in the Wilhelmine years, and the avant-garde continued to mock bourgeois celebration; think only of John Heartfield’s swinelike Prussian Angel, installed at the First International Dada Fair in 1920 and bedecked with a banner featuring lines from Luther’s well-known carol “From Heaven on High,” or his German Yule Tree, with branches twisted into the shape of a swastika. Communist intellectuals and fellow travelers attacked the key values and symbols of the holiday to demonstrate their disrespect for modern consumer culture, organized religion, and general bourgeois values. Hard-edged Christmas poems and stories by Kurt Tucholsky, Bertolt Brecht, Erich Mühsam, Erich Weinert, and Erich Kästner called attention to the impoverishment, unemployment, and chauvinist politics masked by middle-class sentimentalism. Anonymous parodies of church carols such as “Silent Night,” “O How Joyfully,” “From Heaven on High,” and many others updated the Social Democratic alternative culture of the Imperial period. Weimar-era lyrics had a hard edge. Erich Kästner’s anti-Christmas song from the late 1920s, a typical example, satirized the consumerist fantasies of a popular carol with lines such as “tomorrow Father Christmas comes, but only to the neighbors” and “tomorrow children you’ll get nothing.” The KPD mounted a vituperative critique of Christmas in the waning years of Weimar. In marked contrast to their Social Democratic competitors, who walked a delicate line between the rejection of capitalist abuse and appropriation of the conventional holiday, Communists avoided “proletarian” alternatives and indeed called for the abolition of the holiday altogether. Communist propagandists attacked the “preacherly opium” spread by church and state during the holidays, demanding that a call to arms replace the hypocritical sound of the church bells rung by the “class enemy. (…) The violent conflicts on Christmas Eve testify to the overall brutalization of Weimar society in the early 1930s; they also show that German Christmas had become an emotionally laden and politically contested symbol of national prosperity. In the end, the National Socialist version of Christmas ironically appeared to resolve the tensions the Nazis themselves did so much to provoke. Unlike Communist anti-Christmas protests or bourgeois platitudes, the Nazi Christmas envisioned a proud national future based on an invented ethnic past. Its rhetoric and rituals promised to heal the national community with “blood and soil” mythologies, economic recovery, and racial exclusion. After gaining power in 1933, the rhetoric of resentment popular in the “years of struggle” no longer met the needs of a party in power. Instead, National Socialists would use all the resources of an avowedly totalitarian state to promote a harmonious People’s Christmas, which celebrated the values and goals of the Nazi racial state. (…) National Socialist ideologues like Frau Dr. Auguste Reber Gruber, director of the women’s division of the National Socialist Teachers’ Union, were well aware that the familiar imagery of candle-lit trees, snowy landscapes, and regeneration made Christmas a powerful vehicle for naturalizing a radical political culture rooted in a mythic national past. Just as French Jacobins and Russian Bolsheviks transformed their festival cultures in attempts to shape new revolutionary citizens, so National Socialists redesigned Germany’s holidays to conform to the state’s racial and ideological agendas. The Nazi intelligentsia clearly believed that the family rituals performed around the Christmas tree engendered an emotional surplus, which could be manipulated to construct and sustain a sense of national feeling and a “fascist self.” (…) From the start, Christian liturgy, symbols, and sentiments enticed Nazis who sought to appropriate religious and family rituals. Reber-Gruber’s own version of a de-Christianized Christmas based on “the myth of blood and the God-willed order of eternal procreation” — her attempt, in short, to supplant the birth of Christ with the birth of an archetypal “Aryan” child — revealed the constant slippage between piety and politics, race and religion, and Christian ritual and pagan rite that defined Nazi celebration. Borrowing from their Social Democratic adversaries, Nazi propagandists cast Christmas and the winter solstice as a metaphor for the rebirth of the German nation. Family celebration, according to Nazi authors, preserved the ethos of the pagans, when “the feeling of unity with native soil and nature was still alive, the desire for light and strength had strong roots, [and] Yule festivities remained a sacred manifestation of God.” The recovery of mythic Nordic rites hardly ruled out appeals to the Christian aspects of the holiday.

Christmas in the Third Reich (Chapter five)

Parroting the conclusions of late nineteenth-century ethnographers, Nazi loyalists asserted that the “merging of national characteristics and Christianity” exemplified in Christmas revealed the origins of “the German character. (…) After the National Socialists took power in 1933, the parties and celebrations organized by local party offices (Ortsgruppen), the SA storm troopers, the National Socialist League of Women, and the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth, or HJ) all deemphasized Christian and pagan observance and instead played up the supposedly universal German aspects of the holiday.