* * *

Andrew Shea’s paintings, the subject of an exhibition at J.J. Murphy Gallery, are quiet in their ambition and deceivingly modest in scope. The show’s title, “Grocery Slips,” couldn’t be more unostentatious, connoting, as it does, a vestige of everyday life that most of us can hardly be bothered with. The subjects of the canvases are similarly commonplace: the morning’s first cup of coffee, an afternoon siesta, one’s belongings refracted in a mirror, and, well, what is it that’s happening in the painting titled “9 A.M.”?

A figure at her morning toilette, perhaps; a woman huddling in a dense robe, maybe. The scene is energized with a flurry of chromatic grays, and situated within an expanse of milky green. Selective dabs of ochre, blue, and red, along with gray, black, and ivory, dance toward the left of the composition, suggesting objects in the distance. How important is it that the viewer pin down the specifics of an image? Not much: It is enough that Mr. Shea has given permanence to a moment otherwise lost in the passage of time.

* * *

“Grocery Slips” is the first New York City exhibition of a painter who has made a name for himself as an art critic, having written for the Wall Street Journal, the New Criterion, and the Brooklyn Rail. Mr. Shea is a rarity in a field renowned for its lumpish and often obscurantist jargon. His prose is supple, his eye nuanced, and his temperament appreciative — though he is capable of being pointed when the subject warrants skepticism. The German painter Gerhard Richter, Mr. Shea wrote in a memorable apercu, “has the whimsicality of an accountant.”

How well does the wordsmith fare as a painthandler? The tool most in evidence is among the least gainly: a palette knife. Imagine rendering an image in a manner not unlike spreading cream cheese on a bagel: detail and finesse are sacrificed for blunt shapes and a generous physicality. As a result, Mr. Shea’s paintings are endowed with a lush and somewhat counterintuitive monumentality. The surfaces are sumptuous to behold.

* * *

Mr. Shea claims as inspirations the poets William Carlos Williams and James Schuyler, temperaments who sought to underscore (pace Schuyler) “a nothing day full of wild beauty.” A similar elevation of the ordinary occurs in the intimisme of Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard. The former divined within the accumulative process of layering oils an underlying tenderness beneath the prosaic; the latter put brush to canvas with a terse obdurance and sneaking psychological portent. Mr. Shea is in direct correspondence with these precedents, and acquits himself handsomely in the process.

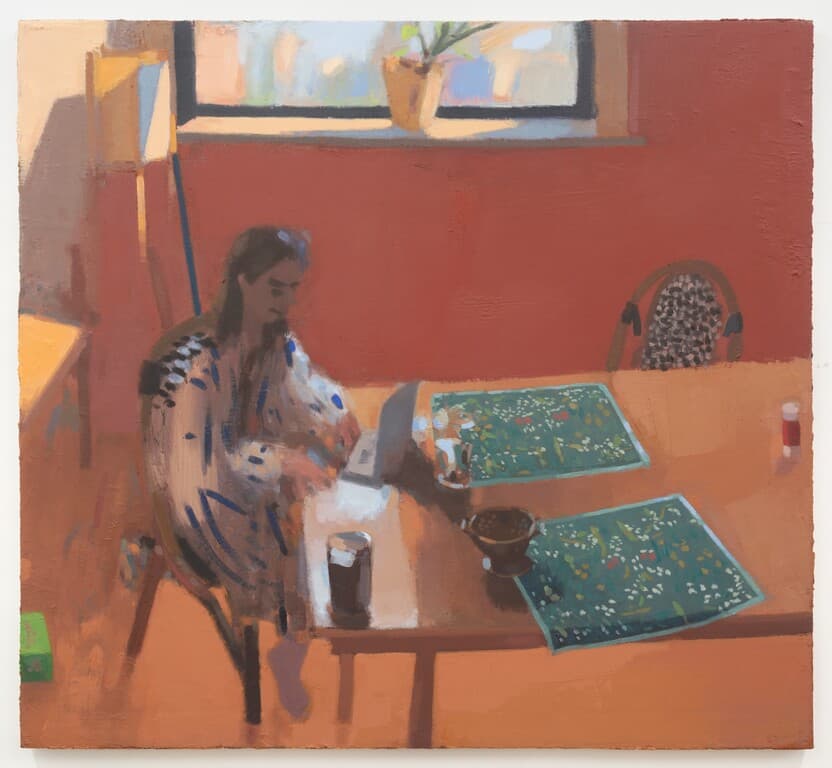

By virtue of its scale, the largish “Morning Coffee” (2025) should count as the show-stopper, and, truth to tell, its bravura run of warm, unnameable colors has much to recommend to it. But Mr. Shea has a gift with small formats, for condensed areas of real estate that prompt an exacting focus on suggestion. The cool grays that dominate “Wickenden Breakfast” and the tawny range of hues seen in “Drawing Session (A+B)” (2024) seem to expand beyond the borders of the canvases, endowing their miniaturist mises en scène with both gravity and grace.

For those who treasure art for how it can elaborate on the vagaries of everyday experience, Mr. Shea’s fetching array of “residual gestures” should not be missed.

(c) 2025 Mario Naves

This review was originally published in the October 30, 2025 edition of “The New York Sun.”