The precuneus is still an elusive element of the brain. It is the result of an anteroposterior functional gradient integrating body perception and vision, and a dorsoventral gradient integrating this visuospatial frame with episodic memory and autonoetic projections. The body is used as a sort of metric unit to “travel” through physical, chronological, mnemonic, and social spaces. It is like the “homunculus” we throw on Google Maps to explore a virtual environment, and run through imagined pixel-based landscapes. Namely, the precuneus is a key node for mental imaging, consciousness, and self-construction.

This week, we have published a still-missing study on this key cortical region: ontogeny. We have analyzed shape and size variations in the precuneus from birth to early adulthood. Here are the main results. First, its growth is largely associated with general brain growth, mostly in the first two years after birth, reaching a plateau before five years of age. Second, during this early period, there are only minor shape changes, which include a bit of dorsal extension. Therefore, the expansion of the precuneus (and its contribution to dorsal brain bulging) is distributed through the pre- and postnatal stages, although the former period is probably more relevant, in this sense. Third, the outstanding individual diversity can be detected in all age groups, since birth. This is particularly important, because it means that this pronounced diversity must originate prenatally, influenced by intrauterine or genetic factors. Fourth, although the precuneus dorsal extension represents the main feature involved in its variations, there are multiple factors involved in its morphology, likely due to the many topological influences of the neighboring regions. Fifth, the dorsal and ventral regions of the precuneus are not much integrated, as they belong to distinct morphological modules. The dorsal region fades into the superior parietal lobule, and should probably be interpreted as its hidden deep part. The ventral region fades instead into the posterior cingulate and retrosplenial areas, without a clear boundary. This separation is also relevant when dealing with aging. The subparietal sulcus could probably be used as a conventional and operational reference to separate these two morphological blocks. It is hence mandatory to keep these two regions separated, when analyzing structural and functional features of the posteromedial parietal cortex.

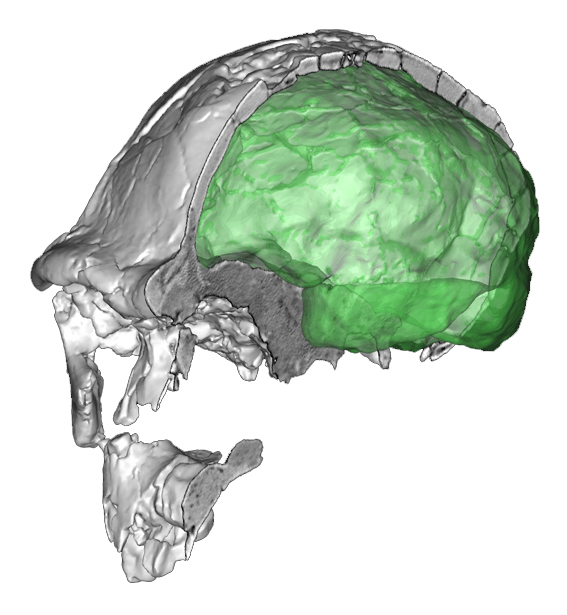

The precuneus displays a noticeable diversity in adult humans, mostly in its longitudinal proportions. These variations are due to differences in cortical surface area. Nonetheless, its variability also concerns the vertical extension, and the sulcal patterns. The main focus of diversity is localized in its dorsal and anterior region, the one most involved in somatic awareness. It is much more expanded in humans, when compared with apes. Probably, it is also more expanded in Homo sapiens, when compared with extinct hominids. Such evolutionary change could have occurred recently, say in the last 50-100 thousand years. The precuneus is also a hot target for neurodegeneration, possibly because of its functional and structural complexity. You can find a list of posts on the precuneus right here.

What is left? Well, surely many details, but the main mystery is still the complex (and unclear) association between anatomical and cognitive variability.