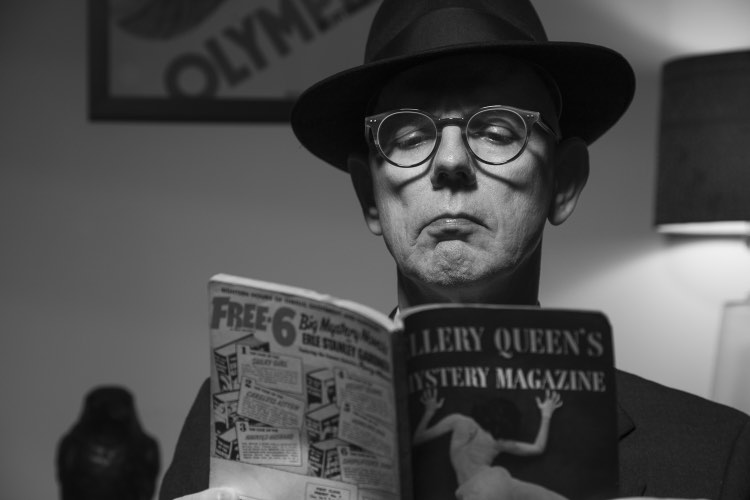

Tapani Bagge is a prolific mystery-fiction writer who has penned over 170 books, including novels, short story collections, and works of young-adult fiction. He makes his EQMM debut in our Jan/Feb 2026 issue with “The Yellow Dog,” translated by EQMM regular Josh Pachter. In this blog post, Bagge discusses the history of Finnish crime fiction while highlighting some of the most important crime-fiction authors and stories to originate from his home country

While Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841) is usually acknowledged as being the first true detective story and Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone (1868) is generally considered to be the world’s first crime novel, crime fiction in Finland is a comparatively new phenomenon, dating back to shortly after the turn of the Twentieth Century, when journalist R.R. Ruth (writing as Rikhard Hornanlinna) published two booklets of Sherlock Holmes-inspired short stories about private detective Max Rudolph in 1910. Verinen lyhty (The Blood on the Lantern) by Jalmari Finne, the first Finnish crime novel, followed in 1928; it’s an entertaining countryside murder case featuring the actual forensics of the time.

The 1930s saw the first appearances of two great detectives, Martti Löfberg’s Inspector Kairala and Mika Waltari’s Inspector Palmu. Waltari also wrote some excellent noirish short novels, including 1937’s Ei koskaan huomispäivää (No Tomorrow). The first Finnish police procedurals were written by Hugo Nousiainen, himself a detective; his best novel, Yöpäivystäjät (Night Watch), published in 1949, is downright noir. And Jorma Napola created the first Finnish hardboiled private eye in 1962, with Ruuvikierre (The Turn of the Screw).

From 1956 to 1984, Finland’s mystery scene was dominated by Mauri Sariola’s Inspector Susikoski, though 1976 saw the beginning of a new era of police procedurals, when Matti Yrjänä Joensuu—a policeman well-versed in the works of Dostoevsky—wrote Väkivallan virkamies (An Official of Violence).

Leena Lehtolainen was one of the first Finns to write crime fiction from a female police detective’s point of view; her Maria Kallio series began with Ensimmäinen murhani (My First Murder)in 1993, now numbers seventeen novels, has been published in twenty-nine languages (including English), and has been adapted for television in a two-season series that’s available on Prime Video.

Harri Nykänen put criminals center stage in 1986. He’s best known for his Raid series, about a contract killer with a kind heart. And my own Hämeenlinna Noir series—which consists of nine novels published between 2002 and 2018—depicts the exploits of crooks in my hometown of Hämeenlinna (about an hour north of Helsinki and also the birthplace of the composer Sibelius).

More recently, Seppo Jokinen wrote a long and dependable procedural series about Inspector Koskinen from 1996 to 2025, and Jarkko Sipilädid the samewith his Helsinki Homicide series from 2001 to 2022.

Today there are a slew of policemen, both former (Marko Kilpi, Christian Rönnbacka, Kale Puonti) and still on the force (Niko Rantsi), writing great crime novels. And a few authors—such as Markku Ropponen, Antti Tuomainen, Tuomas Lius, Joona Keskitalo, and me—are producing crime fiction with a humorous bent, a la Donald Westlake and Elmore Leonard. I should also mention JP Koskinen, whose Murhan vuosi (The Murder Year) is a superb twelve-part-series that can be read separately or as one long novel.

Two rising trends in contemporary Finnish crime fiction are cozies and historicals. I pioneered the latter in 2009 with my first Väinö Mujunen novel, Valkoinen hehku (White Heat). The first four books in that series followed Mujunen and Finland into the Second World War and then out of it. There are now ten novels in the series. My first story in EQMM is “The Yellow Dog,” which was translated by Josh Pachter (who also helped me with this blog post). It follows Mujunen through his first case in the Helsinki Burglary Squad, in the summer of 1927. Later in the ’20s, Mujunen worked in the Murder Squad, then beginning in 1930 in the Finnish State Police, and after the Second World War as a private detective. The most recent novel in the series, Lyijynharmaa taivas (Lead-Gray Sky), is set in January of 1956, just before the presidential election that heated the nation.

So although Finnish crime fiction is relatively new compared to the work of American and British authors like Poe and Collins, our authors have made and continue to make important contributions to the genre. I’m pleased to be the first Finn translated into English for the readers of EQMM, and I hope there’ll be more of us in the years to come. As we say in Finland, “Tyvestä puuhun noustaan”, or “You have to start at the beginning!”