I disappeared again – I’m sorry.

I’m trying to decide whether I’m done with this whole blogging malarky – there are aspects I miss – but I get overwhelmed with the effort it takes me now. So, if I do stick around, I might need to change the kinds of posts I publish and focus less on the long review posts I used to write, and would prefer to write if I could. I will return to reading other people’s blog posts when I can and just see how I feel over the next couple of months.

So here’s some reading highlights from the last few weeks.

Months ago I was fortunate enough to to be sent a review copy of Small Bomb at Dimperly (2024) by Lissa Evans. It was something to look forward to having so enjoyed her previous novels, Crooked Heart, Old Baggage and V for Victory. This novel introduces some new characters, set just as WW2 comes to an end. Corporal Valentine Vere-Thissett, finds himself a reluctant heir to a dilapidated estate. The house filled with assorted relatives and dusty taxidermy. Zena Baxter, working as secretary to Valentine’s eccentric old uncle, has fallen in love with the place – it’s a million miles from where she lived in London before she was evacuated as an expectant mother. Now her little daughter runs around the gardens happily and Zena is loath to return to London. This was such an excellent read – great characterisation and a brilliant setting.

My feminist book group chose to read The Holiday Friend (1972) by Pamela Hansford Johnson for our September discussion. It was a thoroughly engrossing read – one of PHJ’s later novels, it has a very seventies feel in parts – though, my group did all think that it could easily have been set/written twenty or thirty years earlier. Gavin and Hannah Eastwood are a very happily married couple on holiday on the Belgian coast with their very overprotected son Giles – who is nearly twelve. Melissa – a young student of Gavin’s is also in the village, staying at a much cheaper hotel – she deliberately followed the family, having decided that she is hopelessly in love with Gavin. There are several fascinating things here – the dynamics between everyone being the main one. This is a less humorous novel than some of PHJ’s more satirical novels, it’s much darker – and the ending is quite extraordinary. The author really leads the reader up the garden path.

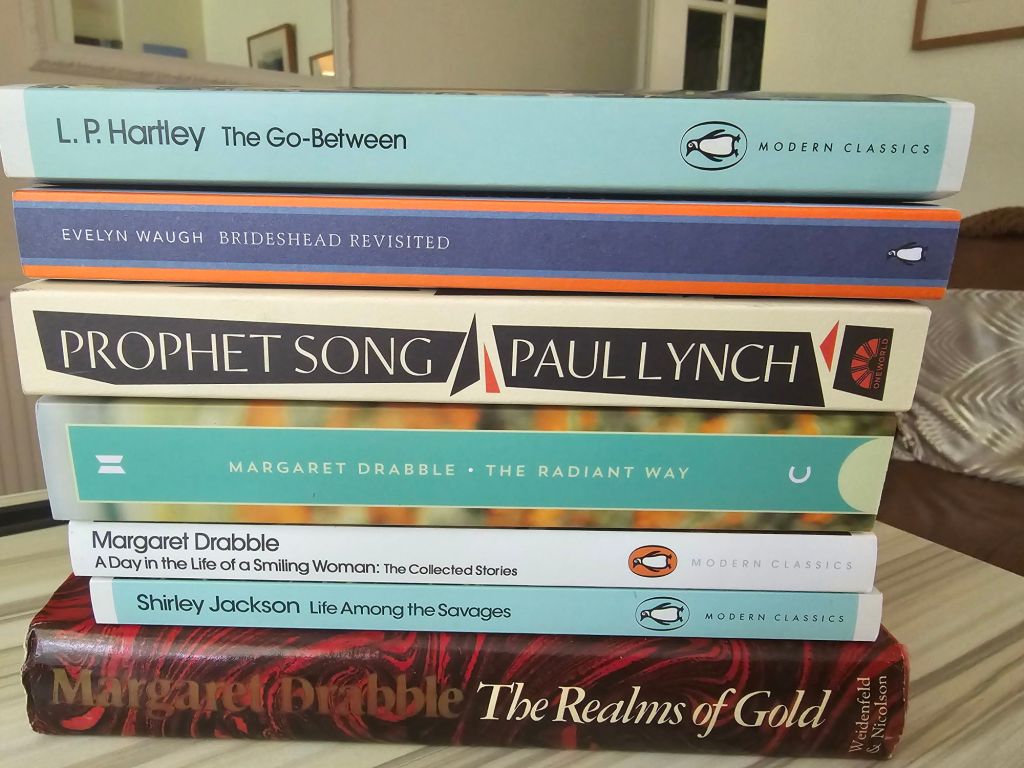

My most recent read in my Margaret Drabble reading of 2024 The Witch of Exmoor (1996) was another hit. I continue to enjoy Drabble enormously. This is a complex literary novel – though I must say I find Margaret Drabble so readable – she’s worth spending a little more time on. This novel is about an elderly, eccentric writer and her three rather grasping adult children. It was a wonderfully sharply observed tale.

My most memorable real page turners I would say were Appointment with Yesterday (1972) by Celia Fremilin and Late and Soon (1943) by E M Delafield. Fremlin is just a master of atmosphere and I was obliged to sit up late with this one. It tells the story of a woman who arrives in a small seaside town with just a small amount of money in her pocket and no luggage – operating under an assumed name she is running from something that happened in the home she shared with her second husband. She spends her first night on a bench on the prom, determined to find a job and accommodation the following day. She’s terrified of the shadow that hangs over her – and gradually as she begins work as a daily help and gets a room in a lodging house, we see in flashback the life she had been living before. Trapped in a dark, claustrophobic basement flat, struggling to cope with the paranoid delusions of her new husband.

E M Delafield is less heart stopping perhaps – but just as compelling. Valentine Arbell is a middle aged widow living with her brother – and younger daughter in a large uncomfortable country house. Her eldest daughter lives in London, and rarely visits. When Colonel Lonergan is given a billet in her house she is delighted to find he is her old teenage flame. The relationship that inevitably reignites, is complicated by the fact Lonergan has had a relationship with Valentine’s older daughter Primrose, a cold, sneering young woman whose biting sarcasm is especially aimed at her mother.

A couple of other recent reads include The British Library women’s writers collection of stories Stories for Summer (2024) which contains stories by all the kinds of writers I love. Cat’s Eye (1988) by Margaret Atwood – a reread after more than thirty years, I had forgotten what a long book it was. I read on Kindle. A brilliant evocation of childhood, exploring, art, memory and perception. I am looking forward to discussing it with my book group next week. I treated myself to the hardback of The Hazlebourne Ladies Motorcycle and Flying Club (2024) by Helen Simonson. Set just after the end of WW1, it’s a thoroughly entertaining read, with lots of brilliant feisty female characters and Simonson does quite well in showing how women had to fight to retain the small bits of independence they had begun to get during WW1 and were already beginning to lose.

Well I have worn myself out, so I will end it there. I hope I will be back soon – but if you don’t hear from me don’t worry, I’ll just be hiding again.