Abstract

An attempted definition of true randomness in the context of gambling and games is defended against the charge of not being mathematical. That definition tries to explain which properties true randomness should have. It gets defended by explaining some properties quantum randomness should have, and then comparing actual mathematical consequences of those properties.

One reason for the charge could be different feelings towards the meaning of mathematical existence. A view that mathematical existence gains relevance by describing idealizations of real life situations is laid out by examples of discussions I had with different people at different times. The consequences of such a view for the meaning of the existence of natural numbers and Turing machines are then analysed from the perspective of computability and mathematical logic.

Introduction

On 20 May 2021 I wrote the following to NB:

Das kleine Büchlein “Der unbegreifliche Zufall: Nichtlokalität, Teleportation und weitere Seltsamkeiten der Quantenphysik” von Nicolas Gisin erklärt toll, wie es zu dem Paradox kommt, dass die Quantenmechanik lokal und nichtlokal gleichzeitig ist: Der Zufall selbst ist nichtlokal, und er muss wirklich zufällig sein, weil sonst diese Nichtlokalität zur instantanen Signalübertragung verwendet werden könnte. Damit wird der Zufall gleichzeitig aber auch entschärft, weil jetzt klar ist, im Sinne welcher Idealisation der Zufall perfekt sein muss. Denn den absolut mathematisch perfekten Zufall gibt es vermutlich gar nicht.

If that mail were written in English, it might have read:

Nicolas Gisin’s short book Quantum Chance nicely explains how the paradox arises that quantum mechanics is local and nonlocal at the same time: The randomness itself is nonlocal, and it must be really random, because otherwise this non-locality could be used for instantaneous signal transmission. At the same time, however, the randomness also becomes less problematic, because it is now clear in the sense of which idealization it must be perfect. After all, there is probably no such thing as mathematically perfect true randomness.

I remembered this recently, when Mateus Araújo put out the challenge to define true randomness beyond a mere unanalysed primitive, and I decided to give it a try. His replies included: “I’m afraid you misunderstood me. I’m certain that perfect objective probabilities do exist.” and: “My challenge was to get a mathematical definition, I don’t see any attempt in your comment to do that. Indeed, I claim that Many-Worlds solves the problem.” I admitted that: “I see, so you are missing the details how to connect to relative frequencies” and “You are right that even if I would allow indefinitely many … I agree that those details are tricky, and it is quite possible that there is no good way to address them at all.” (I now clarified some details.)

I can’t blame Mateus for believing that I misunderstood him, and for believing that my attempt had nothing to do with a mathematical definition. He is conviced that “perfect objective probabilities do exist”, while I am less certain about that, as indicated by my mail above, and by the words I used to introduce my attempt: “Even if perfect objective probabilities might not exist, it still makes sense to try to explain which properties they should have. This enables to better judge the quality of approximations used as substitute in practice, for the specific application at hand.” The next section is my attempt itself:

True randomness in the context of gambling and games

I wrote: “Indeed, the definition of a truly random process is hard.” having such practical issues in applications in mind. In fact, I had tried my luck at a definition, and later realized one of its flaws:

The theories of probability and randomness had their origin in gambling and games more general. A “truly random phenomenon” in that context would be one producing outcomes that are completely unpredictable. And not just unpredictable for you and me, but for anybody, including the most omniscient opponent. But we need more, we actually need to “know” that our opponent cannot predict it, and if he could predict it nevertheless, then he has somehow cheated.

But the most omniscient opponent is a red herring. What is important are our actual opponents. A box with identical balls with numbers on them that get mixed extensively produces truly random phenomena, at least if we can ensure that our opponents have not manipulated things to their advantage. And the overall procedure must be such that also all other possibilities for manipulation (or cheating more generally) have been prevented. The successes of secret services in past wars indicate that this is extremely difficult to achieve.

The unpredictable for anybody is a mistake. It must be unpredictable for both my opponents and proponents, but if some entity like nature is neither my proponent nor my opponent (or at least does not act in such a way), then it is unproblematic if it is predictable for her. An interesting question arises whether I myself am necessary my proponent, or whether I can act sufficiently neutral such that using a pseudorandom generator would not yet by itself violate the randomness of the process.

(Using a pseudorandom generator gives me a reasonably small ID for reproducing the specific experiment. Such an ID by itself would not violate classical statistics, but could be problematic for quantum randomness, which is fundamentally unclonable.)

Serious, so serious

The randomness of a process or phenomenon has been characterized here in terms of properties it has to satisfy:

- Quantum mechanics: The randomness itself is nonlocal, and it must be really random, because otherwise this non-locality could be used for instantaneous signal transmission.

- Gambling and games: A truly random phenomenon must produce outcomes that are completely unpredictable. And not just unpredictable for you and me, but unpredictable for both my opponents and proponents.

I consider the properties required in the context of quantum mechanics to be weaker than those required for “mathematically perfect true randomness”. The properties I suggested to be required and sufficient in the context of gambling and games are my “currently best” shot at nailing those properties required for “mathematically perfect true randomness”.

Being “unpredictable for you and me” seems to be enough to prevent “this non-locality being used for instantaneous signal transmission”. Since “you and me” are the ones who choose the measurement settings, no “opponent or proponent” can use this “for instantaneous signal transmission,” even if they can predict more of what will happen.

Is this enough to conclude that those properties are weaker than true randomness? What about Mateus’ objection that he doesn’t see any mathematical definition here? At least time-shift invariant regularities are excluded, because those could be learned empirically and then used for prediction, even by “you and me”. The implication “and if he could predict it nevertheless, then he has somehow cheated” from the stronger properties goes beyond time-shift invariance, but is hard to nail down mathematically. How precisely do you check that he has predicted it? If I would play lotto just once in my life and win the jackpot at odds smaller than 1 : 4.2 million, then my conclusion will be that one of my proponents has somehow cheated. This is not what I meant when I wrote: “I agree that those details are tricky, and it is quite possible that there is no good way to address them at all.” The tricky part is that we are normally not dealing with a single extremely unlikely event, but that we have to cluster normal events together somehow to get extremely unlikely compound events that allow us to conclude that there has been “cheating”. But what are “valid” ways to do this? Would time-shift invariant regularities qualify? In principle yes, but how to quantify that they were really time-shift invariant?

Even so I invented my “currently best” shot at nailing the properties required for true randomness as part of a reply to a question about “truly random phenomena,” only tried to fix one of its flaw as part of another reply, and only elaborated it (till the point where unclear details occured) in reaction to Mateus’ challenge and objections, I take it serious. I wondered back then whether there are situations where all the infinite accuracy provided by the real number describing a probability would be relevant. I had the idea that it might be relevant for the concept of a mixed-strategy equilibrium introduced by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern for two player zero-sum games, and for its generalization to a mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium. I am neither Bayesian nor frequentist, instead of an interpretation, I do believe that game theory and probability theory are closely related. This is why I take this characterization of true randomness so serious. And this is why I say that my newer elaborations are different in important details from my older texts with a similar general attitude:

One theoretical weakness of a Turing machine is its predictability. An all powerful and omniscient opponent could exploit this weakness when playing some game against the Turing machine. So if a theoretical machine had access to a random source which its opponent could not predict (and could conceal its internal state from its opponent), then this theoretical machine would be more powerful than a Turing machine.

Ways to belief in the existence of interpretations of mathematical structures

Dietmar Krüger (a computer scientist I met in my first job who liked lively discussions) stated that infinity does not exist in the real world. I (a mathematician) tried to convince him otherwise, and gave the example of a party ballon: it is never full, you can always put a bit more air into it. Of course, it will burst sooner or later, but you don’t know exactly when. My point was that finite structures are compact, but the party ballon can only be described appropriately by a non-compact structure, so that structure should not be finite, hence it should be infinite. Dietmar was not convinced.

Like many other mathematicians, I believe in a principle of ‘conservation of difficulty’. This allows me to believe that mathematics stays useful, even if it would be fictional. I believe that often the main difficulties of a real world problem will still be present in a fictional mathematical model.

…

From my experience with physicists (…), their trust in ‘conservation of difficulty’ is often less pronounced. As a consequence, physical fictionalism has a hard time

This quote from my reply to Mathematical fictionalism vs. physical fictionalism defends this way to believe in mathematical existence. I just posted an english translation of my thoughts on “Why mathematics?” from around the same time as my discussion with Dietmar. It expresses a similar attitude and gives some of the typical concrete “mathematical folklore” examples.

My point is that concrete interpretations of how a mathematical structure is some idealization of phenomena occuring in the real world are for me something on top of believing in the Platonic existence of mathematical structures, not something denying the relevance of Platonic existence. My attempts to understand which properties a source of randomness should have in the real world to be appropriately captured by the concept of true randomness are for me a positive act of faith, not a denial of the relevance or existence of true randomness.

I once said in the context of a Turing machine with access to a random source:

The problem with this type of theoretical machine in real life is not whether the random source is perfectly random or not, but that we can never be sure whether we were successful in concealing our internal state from our opponent. This is only slightly better than the situation for most types of hypercomputation, where it is unclear to me which idealized situations should be modeled by those (I once replied: So I need some type of all-knowing miracle machine to solve “RE”, I didn’t know that such machines exists.)

My basic objection back in 2014 was that postulating an oracle whose answer is “right by definition” is not sufficiently different from “a mere unanalysed primitive” to be useful. At least that is how I interpret it in the context and words of this post. My current understanding has evolved since 2014, especially since I now understand on various levels the ontological commitments that are sufficient for the model existence theorem, i.e. the completeness theorem of first order predicate logic. Footnote 63 on page 34 of On consistency and existence in mathematics by Walter Dean gives an impression of what I mean by this:

For note that the  sets also correspond to those which are limit computable in the sense of Putnam and Shoenfield (see, e.g., Soare 2016, §3.5). In other words

sets also correspond to those which are limit computable in the sense of Putnam and Shoenfield (see, e.g., Soare 2016, §3.5). In other words  is

is  just in case there is a so-called trial and error procedure for deciding

just in case there is a so-called trial and error procedure for deciding  – i.e. one for which membership can be determined by following a guessing procedure which may make a finite number of initial errors before it eventually converges to the correct answer.

– i.e. one for which membership can be determined by following a guessing procedure which may make a finite number of initial errors before it eventually converges to the correct answer.

And theorem 5.2 in that paper says that if an arbitrary computably axiomatizable theory is consistent, then it has an arithmetical model that is  -definable. For context, we are talking about sets of natural numbers here, the

-definable. For context, we are talking about sets of natural numbers here, the  -definable sets are the computable sets, the

-definable sets are the computable sets, the  -definable sets are the arithmetical sets (

-definable sets are the arithmetical sets ( ), and the

), and the  -definable sets are the hyperarithmetical sets. The limit computable sets are “slightly more complex” than the computable sets, but less “complex” than the arithmetical sets. I recently wrote:

-definable sets are the hyperarithmetical sets. The limit computable sets are “slightly more complex” than the computable sets, but less “complex” than the arithmetical sets. I recently wrote:

Scott is right that this is a philosophical debate. So instead of right or wrong, the question is more which ontological commitments are implied by different positions. I would say that your current position corresponds to accepting computation in the limit and its ontological commitments. My impression is that Scott’s current position corresponds to at least accepting the arithmetical hierarchy and its ontological commitments (i.e. that every arithmetical sentence is either true or false).

[…]

I recently chatted with vzn about a construction making the enormous ontological commitments implied by accepting the arithmetical hierarchy more concrete:

“…”

The crucial point is that deciding arithmetical sentences at the second level of the hierarchy would require BB(lengthOfSentence) many of those bits (provided as an internet offering), so even at “1 cent per gigabyte” nobody can afford it. (And for the third level you would even need BBB(lengthOfSentence) many bits.)

Now you might think that I reject those ontological commitments. But actually I would love to go beyond to hyperarithmetic relations and have similarly concrete constructions for it as we have for computation in the limit and the arithmetical hierarchy.

Ontological commitments in natural numbers and Turing machines

- Why can we prove the model existence theorem, without assuming ZFC, or even the consistency of Peano arithmetic?

- Why can’t we prove the consistency of Peano arithmetic, given the existence of the natural numbers, and the categorical definition of the natural numbers via the second order induction axiom?

Back in 2014, I replied to the question “Are there any other things like ‘Cogito ergo sum’ that we can be certain of?” that Often the things we can be pretty certain of are ontological commitments:

Exploiting ontological commitments

A typical example is a Henkin style completeness proof for first order predicate logic. We are talking about formulas and deductions that we “can” write down, so we can be pretty certain that we can write down things. We use this certainty to construct a syntactical model of the axioms. (The consistency of the axioms enters by the “non-collapse” of the constructed model.)

What ontological commitments are really there?

One point of contention is how much ontological commitment is really there. Just because I can write down some things doesn’t mean that I can write down an arbitrarily huge amount of things. Or maybe I can write them down, but I thereby might destroy things I wrote down earlier.

What ontological commitments are really needed?

For a completeness proof, we must show that for each unprovable formula, there exists a structure were the unprovable formula is false and all axioms are true. This structure must “exist” in a suitable sense, because what else could be meant by “completeness”? If only the structures that can be represented in a computer with 4GB memory would be said to “exist”, then first order predicate logic would not be “complete” relative to this notion of “existence”.

One intent of that answer was to relativize the status of ‘cogito ergo sum’ as the unique thing we can be 100% certain of, by interpreting it as a normal instance of a conclusion from ontological commitments. But it also raised the question about the nature and details of the ontological commitments used to prove the model existence theorem: “We can’t prove that the Peano axioms are consistent, but we can prove that first order predicate logic is sound and complete. Isn’t that surprising? How can that be?”

I wondered which other idealizations beyond the existence of finite strings of arbitrary length have been assumed and used here. Two days later I asked Which ontological commitments are embedded in a straightforward Turing machine model?

I wonder especially whether the assumption of the existence of such idealized Turing machines is stronger than the mere assumption of the existence of the potential infinite corresponding to the initial state of the tape. By stronger, I mean that more statements about first order predicate logic can be proved based on this assumption.

That assumption is indeed stronger than the mere existence of the natural numbers, for example it implies the existence of the computable subsets of the natural numbers (the  -definable sets). But for the model existence theorem, we need the existence of the limit computable sets (the

-definable sets). But for the model existence theorem, we need the existence of the limit computable sets (the  -definable sets). While

-definable sets). While  is representative of the precision and definiteness of mechanical procedures, the trial and error nature of

is representative of the precision and definiteness of mechanical procedures, the trial and error nature of  better captures the type of historically contingent slighlty unsure human knowledge. Or at least it was my intial plan to argue along these lines in the context of this post. But it doesn’t work. Neither

better captures the type of historically contingent slighlty unsure human knowledge. Or at least it was my intial plan to argue along these lines in the context of this post. But it doesn’t work. Neither  nor unsure human knowledge have anything to do with why the model existence theorem is accepted (both today and historically, both by me and by others).

nor unsure human knowledge have anything to do with why the model existence theorem is accepted (both today and historically, both by me and by others).

The model existence theorem is accepted, because the construction feels so concrete, and the non-computable part feels so small, insignificant, and so “obviously true”. The non-computable part can be condensed down to a weak form of Kőnig’s lemma which states that every infinite binary tree has an infinite branch. The “de dicto” nature of this lemma makes it very weak in terms of ontological commitments. On the other hand, you don’t get a concrete well specified model, only the knowledge that one exists, as a sort of wittness that you won’t be able to falsify the model existence theorem. But any concrete well specified model will be  (or harder), and this “de re” nature at least implicitly implies that you made corresponding ontological commitments. I learned about that “de re/de dicto” distinction from Walter Dean’s talk `Basis theorems and mathematical knowledge de re and de dicto’. (It was different from this talk, and probably also different from my interpretation above.)

(or harder), and this “de re” nature at least implicitly implies that you made corresponding ontological commitments. I learned about that “de re/de dicto” distinction from Walter Dean’s talk `Basis theorems and mathematical knowledge de re and de dicto’. (It was different from this talk, and probably also different from my interpretation above.)

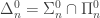

OK, back to  ,

,  and ontological commitments. The interpretation of those

and ontological commitments. The interpretation of those  classes as classes of subsets of natural numbers allows nice identifications like

classes as classes of subsets of natural numbers allows nice identifications like  , but it also hides their true nature. They are classes of partial functions from finite strings to finite strings (or from

, but it also hides their true nature. They are classes of partial functions from finite strings to finite strings (or from  to

to  if you prefer). I have seen notations like

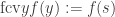

if you prefer). I have seen notations like  for such classes of partial function, in the context of the polynomial hierarchy. Those computable partial functions can be defined by adding an unbounded search operator μ (which searches for the least natural number with a given property) to a sufficiently strong set of basic operations. In a similar way, the limit computable partial functions can be defined by adding a finally-constant-value operator

for such classes of partial function, in the context of the polynomial hierarchy. Those computable partial functions can be defined by adding an unbounded search operator μ (which searches for the least natural number with a given property) to a sufficiently strong set of basic operations. In a similar way, the limit computable partial functions can be defined by adding a finally-constant-value operator  (or a finally-constant-after operator

(or a finally-constant-after operator  if one wants to stay closer to the μ-operator) to a suitable set of basic operations. Using a natural number

if one wants to stay closer to the μ-operator) to a suitable set of basic operations. Using a natural number  , the finally-constant-value operator could be defined as

, the finally-constant-value operator could be defined as  . Using

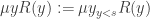

. Using  in a similar way, the unbounded μ-operator

in a similar way, the unbounded μ-operator  can be defined in terms of the bounded μ-operator

can be defined in terms of the bounded μ-operator  as

as  . One could elaborate this a bit more, but let us focus on the role of

. One could elaborate this a bit more, but let us focus on the role of  instead.

instead.

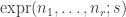

Let  and

and  , where BB is the busy beaver function, and BBB is the beeping busy beaver function. Then

, where BB is the busy beaver function, and BBB is the beeping busy beaver function. Then  will give the “correct” result for computable functions if

will give the “correct” result for computable functions if  , and the “correct” result for limit computable functions if

, and the “correct” result for limit computable functions if  . Because such a function is not necessarily defined for all

. Because such a function is not necessarily defined for all  , the exact meaning of “correct” needs elaboration. For limit computable functions, the function is defined for

, the exact meaning of “correct” needs elaboration. For limit computable functions, the function is defined for  if

if  no longer changes its value (i.e. is constant) for

no longer changes its value (i.e. is constant) for  . For computable function, the stricter criterion that all unbounded search operators found suitable natural numbers

. For computable function, the stricter criterion that all unbounded search operators found suitable natural numbers  must be used instead. Note that for a given natural number N, both BB(N) and BBB(N) can be represented by a concrete Turing machine with N states, which means that the length of its description is of order O(N log(N)), i.e. quite short. But there is a crucial difference: the Turing machine describing BB(N) can be used directly to determine whether a concretely given natural number is smaller, equal or bigger than it, because it is easy to know when BB(n) stopped. But BBB(N) is harder to use, because how should we know whether it will never beep again? OK, each time it beeps, we learn that BBB(N) is greater or equal to the number of steps performed so far. If we had access to BB(.), we could could encode the current state of the tape into a Turing machine T which halts at the next beep, and then use BB(nrStatesOf(T)) to check whether it halts. However, the size of that state will grow while letting BBB(N) run, so that in the end we will need access to BB(N+log(BBB(N)).

must be used instead. Note that for a given natural number N, both BB(N) and BBB(N) can be represented by a concrete Turing machine with N states, which means that the length of its description is of order O(N log(N)), i.e. quite short. But there is a crucial difference: the Turing machine describing BB(N) can be used directly to determine whether a concretely given natural number is smaller, equal or bigger than it, because it is easy to know when BB(n) stopped. But BBB(N) is harder to use, because how should we know whether it will never beep again? OK, each time it beeps, we learn that BBB(N) is greater or equal to the number of steps performed so far. If we had access to BB(.), we could could encode the current state of the tape into a Turing machine T which halts at the next beep, and then use BB(nrStatesOf(T)) to check whether it halts. However, the size of that state will grow while letting BBB(N) run, so that in the end we will need access to BB(N+log(BBB(N)).

Oh well, that attempted analysis of computation in the limit didn’t go too well. One takeaway could be that natural numbers don’t just occur as those concretely given finite strings of digits, but also in the form of those Turing machines describing BB(N) or BBB(N). This section should also hint at another aspect of the idealizations captured by Turing machines related to Kripkenstein’s rule following paradox and a paradox of emergent quantum gravity in MWI. Why the quantum?

– Lienhard Pagel: It is a fixed point, and Planck’s constant h cannot change, not even in an emergent theory on a higher level.

– All is chaos (instead of nothing), and the order propagates through it. The idealization failing in our universe is that things can stay “exactly constant” while other things change. Even more, the idea that it is even possible to define what “staying exactly constant” means is an idealization.

Sean Carroll’s work on finding gravity inside QM as an emergent phenomenon goes back again to the roots of MWI. I find this work interesting, among others because Lienhard Pagel proposed that the Planck constant will remain the same even for emergent phenomena (in a non-relativistic context). But when time and energy (or length and momentum) are themselves emergent, what should it even mean that the Planck constant will remain the same.

Conclusions?

The mail to NB also contained the following:

Eine Konsequenz von Gisin’s Einsichten ist, dass die Viele-Welten Interpretation den Zufall in der QM nicht angemessen beschreibt. Die Welten trennen sich nämlich viel zu schnell, so dass es mehr Zufall zu geben scheint, als man lokal tatsächlich je experimentell extrahieren können wird.

I fear Mateus Araújo would not have liked that. In English:

One consequence of Gisin’s insights is that the many-worlds interpretation does not adequately describe randomness in QM. The worlds separate much too fast, so that there seems to be more randomness than one will ever be able to extract locally experimentally.

However, I changed my mind since I wrote that. I now consider it as a trap that one can fall into, but not as an actual prediction of MWI. That trap is described succinctly in Decoherence is Dephasement, Not Disjointness. I later studied both Sean Carroll’s book and Lev Vaidman’s SEP article, to better understand whether MWI proponents avoid that trap. Lev Vaidman certainly avoids it. But it is a common perception of MWI, for example also expressed by Jim Al-Khalili in Fundamental physics and reality | Carlo Rovelli & Jim Al-Khalili:

… I think more in the direction of deBroglie-Bohm, because metaphysically I find it hard to buy into an infinite number of realities coexisting just because an electron on the other side of the universe decided to go left and right and the universe split into …

Good, but how to end this post? Maybe in the classical way? Of course, this post got longer than expected, as always. It has many parts that should be readable with reasonable effort, but once again I couldn’t stop myself from including technical stuff from logic and computability. Good, but why did I write it, and what do I expect the reader to take away from it? The very reason why I wrote this post is that I had finally worked out details of the role of the model in a specific “operational falsification” interpretation of probability. (Spoiler: it is not a “perfect” interpretation of probability, but it still seems to be internally consistent.) And my recent exchange with Mateus was the reason why I finally did that. Writing this post was just the cherry on the cake, after the hard work was done.