Open Thread

What’s on your mind?

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent | Est. 2002

What’s on your mind?

Owens: "Jewish people were in control of the slave trade." Boller declines to comment.

The Atlantic interviewed Carrie Prejean Boller, the recently removed commissioner of the White House Religious Liberty Commission. (Boller insists that only President Trump can fire her, and not the Chairman; I'm sure she will sue.) Boller maintains that her Catholic faith is inconsistent with (how she perceives) Zionism, and that it is "anti-Christian" to accuse her of anti-semitism.

Yair Rosenberg, who wrote about the Volokh Conspiracy back in 2014, asked Boller to address blatantly anti-semitic comments from Candace Owens. I'll let the interview speak for itself:

As it happens, Owens has said many deranged things about Jews, plenty of which have nothing to do with Israel. So I was surprised to hear her so vigorously defended at a hearing ostensibly devoted to combatting anti-Jewish bigotry. I raised the subject with Boller, who regularly reposts content from Owens on social media, and I quoted several recent claims that the podcaster had made.

On February 2, for instance, Owens praised the decision of General Ulysses S. Grant to expel all Jews from his military district in 1862, during the Civil War. The move was soon reversed by President Abraham Lincoln, and Grant later disavowed it—but Owens did not. "Jewish supremacists," she said, "had everything to do with the Civil War in America. They excel at creating the false dialectic, the North versus the South, the left versus the right. Ulysses S. Grant notoriously expelled Jews from his military district: Tennessee, Mississippi, Kentucky. You think he just—he was just, like, what? Another white supremacist? Everyone's just a white supremacist," she said. "Well, they would have called him a white supremacist" or said that "he was anti-Semitic."

I read this monologue to Boller and asked her if she thought it was anti-Semitic to defend expelling American Jews. "I'm not going to get involved in any of that," she said. "I watched her show, and I have never heard anything out of her mouth that is anti-Semitic. So I'm not gonna make a statement on something that I haven't heard the full context of." I offered to play Boller the audio of this remark in its full context. She declined to listen. So I moved on to another of Owens's greatest hits: blaming American Jews for the African slave trade. This canard has been repeatedly debunked by historians and repeatedly invoked by Owens. "Jewish people were the ones that were trading us," she said in December. "Jewish people were in control of the slave trade. They've buried a lot of it, but it's there and you can find it."

Was this anti-Semitic? "From what I've heard from my ears, from her mouth, I have not heard anything that is anti-Semitic," Boller repeated. Okay, but if someone such as Owens did say such things, it would be anti-Semitic, right? "I'm not playing the 'What if?' game," she said, her previous moral clarity abruptly turning into cagey ambiguity.

I had hoped to ask Boller for her opinion about other claims made by Owens—that "Talmudic Jews" think "that we're animals, that they have a right to own us, that they have a right to make us worship them," and that Israel was complicit in the 9/11 attacks and the assassination of President John F. Kennedy—but she refused to engage and eventually ended the call. Rather than reckon with anti-Semitic statements from those she had defended at a hearing intended to confront anti-Semitism, she repeatedly attempted to reroute our conversation back to the safer ground of criticizing Israel. She either did not realize that she was using anti-Zionism as a pretext to launder vulgar anti-Semitism and its purveyors into the public square, or she did not care.

I think there is enough here for a fifteen minute video.

Anti-semitism is as anti-semitism does. Please do not believe the canard that the fixation on Israel is because of Zionism. The hatred of Jews predates Christianity. It has existed since before the beginning of recorded history. My Christian friends often ask me why have Jews always been persecuted in every civilization. I wish I had an answer. When I was about 10 years old, I asked my Uncle, a Holocaust survivor, that question. He did not have a good answer, though he suggested that it took something like the Holocaust for the Jewish people to return to the land of Israel, and fulfill the biblical covenant. For a very brief moment, the world saw with clarity the need for a Jewish home state in Israel. That moment was far too brief.

More Christians need to speak up to preven Boller and others like her from hijacking their faiths. I appreciate the support from Kelly Shackelford of First Liberty and Bill Donohue of the Catholic League:

Kelly Shackelford, who is president, CEO and Chief Counsel for First Liberty Institute and a member of the Commission, said Ms. Prejean Boller's "attempt to hijack the Commission meeting … was intended to promote an antisemitic agenda, and that was disgusting."

"First Liberty Institute proudly represents synagogues and other Jewish clients, and we will continue to represent their cause as a core part of our mission to defend all people of faith in America," he said.

Ms. Prejean Boller defended her actions on Tuesday, saying on social media that the commission was threatening to remove her over her Catholic faith, which she had converted to in April.

"Can you even imagine this? A Religious Liberty Commission prepared to fire a commissioner for her Catholic faith?" she wrote. "If that happens, it proves their mission was never religious liberty, but a Zionist agenda. I refuse to resign."

Bill Donohue, president of the Catholic League, crowed in a statement Wednesday that the dismissal came just minutes after he called for it.

"At 9:57 a.m. I called for the ouster of Carrie Prejean Boller from President Trump's Religious Liberty Commission. I just learned that the Commission chairman, Dan Patrick, gave her the boot at 10:03 a.m. Kudos to him," he said.

This issue is not going away.

The New York nomination process begins on February 24, and the maps have still not been settled.

In 2010, the Daily Show had a segment on how there were Supreme Court Justices from four of the five boroughs of New York City: Justice Scalia was from Queens, Justice Ginsburg was from Brooklyn, Justice Sotomayor was from the Bronx, and Justice Kagan was from Manhattan. But as Jon Stewart pointed out, there was no Justice from my home borough of Staten Island. I quipped at the time I was available, but I suppose I was delusional even back then.

If SCOTUS won't go to Staten Island, then Staten Island should go to SCOTUS. And so it has come to pass. I have blogged twice about a case that would splice the boundaries of Staten Island's congressional district. Since then, the New York Appellate Division has declined to impose a stay, and the New York Court of Appeals (the highest court in New York) found it lacked jurisdiction. Nicole Maliotakis, the Representative from New York has filed an emergency petition in the Supreme Court.

Here is the summary of the argument:

Congresswoman Nicole Malliotakis and the Individual Voter Applicants (collectively, "Applicants") request a stay of the order of the Supreme Court of the State of New York enjoining state officials from conducting any election under the State's congressional map. The trial court's order has thrown New York's elections into chaos on the eve of the 2026 Congressional Election, which is set to begin on February 24, 2026. Applicants respectfully request emergency relief from this Court by February 23, 2026, so that the election can begin on February 24, under the legislatively adopted congressional map. Applicants presented this stay request to both the New York Appellate Division and Court of Appeals, asking for relief by February 10 so Applicants could give this Court a reasonable opportunity to grant them relief before February 24, if necessary. The New York Court of Appeals yesterday determined it lacks jurisdiction to give relief, and the Appellate Division has not yet acted. Petitioners are keenly aware of how seriously this Court takes the principle that "courts should ordinarily not alter the election rules on the eve of an election," Abbott v. League of United Latin Am. Citizens, 146 S. Ct. 418, 419 (2025) (citation omitted), so they come to this Court before there is any suggestion that the election has begun, which is scheduled to occur on February 24. . . .

This Court is likely to reverse the trial court's order if it were upheld by the New York appellate courts on any of three grounds. First, the decision clearly violates this Court's Equal Protection Clause case law by prohibiting New York from running any congressional elections until it racially gerrymanders CD11 by "adding [enough] Black and Latino voters from elsewhere," until the Black and Latino voters in CD11 control contested primaries and win most general elections. Although Applicants repeatedly told the trial court that racially reconfiguring CD11 would violate this Court's binding strict-scrutiny framework, the trial court ignored this argument. This Court summarily reversed in less egregious circumstances in Wisconsin Legislature v. Wisconsin Elections Commission, 595 U.S. 398 (2002) (per curiam). Second, the trial court's decision violated due process and related party-presentation principles by deciding the case based upon a theory that no party briefed, and that the Williams Respondents did not even present evidence to satisfy. Those are more extreme circumstances than those at issue in this Court's recent summary reversal in Clark v. Sweeney, 607 U.S. 7 (2025) (per curiam). Finally, the trial court violated the Elections Clause under Moore v. Harper, 600 U.S. 1 (2023), by adopting an unbriefed, atextual test to invalidate a legislatively-adopted congressional map.

The timing here supports Malliotakis's application. The nomination process begins on February 24. The lesson from Texas and Cailfornia is not to change maps on the eve of the election. This isn't quite Purcell, but as I noted, the midterm primary date is the relevant deadline.

All equitable considerations call out for an immediate stay. Under New York law, the 2026 Congressional Election begins on February 24, 2026, when nominating petitions can start circulating. Congresswoman Malliotakis and her individual voter supporters who make up the Applicants have a right to begin their election activity for this federal office on that date. Yet, under the trial court's order, the New York Board of Elections cannot take any steps to hold the election under the New York congressional map, unless and until CD11 is racial gerrymandered. At the same time, the trial court's remedial mechanism—requiring New York's Independent Redistricting Commission ("IRC") to racially gerrymander CD11—is automatically stayed by operation of state law. That is a recipe for unconstitutional chaos, with no map in place and uncertainty as to whether nominating petitions can start circulating on February 24, with no end in sight. Applicants and the People of New York have the right to conduct their congressional elections under the lawful map that the New York Legislature adopted starting on February 24, free from a judicial mandate that violates multiple provisions of the United States Constitution. While Applicants had hoped—and still hope—that the New York appellate courts put an end to this unconstitutional mischief, they come to this Court now, so that this Court can provide relief before February 24, if the New York appellate courts do not do so.

I think is it relevant that the New York Court of Appeals dragged their feet after the Supreme Court's GVR in Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany, as well as the Yeshiva University case. This track record does not inspire much confidence that the New York Court system will figure everything out in a few weeks.

The parties did not ask for an administrative stay, so the only thing for Circuit Justice Sotomayor to do is refer the matter to the Court.

A “sensitive place” requires comprehensive security and proper historical analogues.

On February 11, the Third Circuit en banc heard oral argument in Koons v. Attorney General, which concerns New Jersey's post-Bruen ban on firearm possession in numerous public places. A panel decision previously upheld 2-1 most of the verboten locations as "sensitive places" where the Second Amendment right does not apply. As I discussed here, the decision was based on a flawed misreading of supposed historical analogues. Its basic premise is that a "sensitive place" is anything a legislature says it is without Founding-era analogues and without providing comprehensive security like that in modern courthouses and in the sterile area of airports (once you go past TSA screening).

We start with the Supreme Court's methodology in Bruen that "when the Second Amendment's plain text covers an individual's conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct. To justify its regulation, … the government must demonstrate that the regulation is consistent with this Nation's historical tradition of firearm regulation." This means, as Rahimi put it, "the appropriate analysis involves considering whether the challenged regulation is consistent with the principles that underpin our regulatory tradition." Here, that burden to demonstrate the existence of a historical tradition as well as the extraction of the appropriate principles falls squarely upon New Jersey. And while New Jersey demonstrated neither, it was the instant plaintiffs that established the existence of a historically-based principle of the Supreme Court's "sensitive places" doctrine as discussed below.

Previously, in Heller, the Court in dicta referred to "laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings" as being "presumptively lawful," implying that the presumption may be subject to question, narrowing, or clarification. Bruen – again in dicta – specifies "government buildings" that are sensitive places to include "legislative assemblies, polling places, and courthouses." However, in Bruen, the Court rejected New York's argument that it had the authority consistent with the Second Amendment to ban the carrying of handguns by claiming its restrictions were essentially "sensitive place" regulations. The Court specifically said that, for example, Manhattan could not constitutionally be considered a gun free zone "sensitive place" because it is crowded and police are generally present.

The provision of government security ties these historic "sensitive place" locations together. At the Founding, governments provided enhanced security at those locations, in the persons of bailiffs, justices of the peace, sergeants-at-arms, doorkeepers, and sheriffs. While covered in the briefs, these historical analogues are set forth in much greater detail in Dr. Angus McClellan's recent SSRN post. So, the three locations identified by Bruen were sensitive places because they were provided with enhanced armed security, and they are proper historical analogues with roots in the Founding.

Faced with defending gun bans in numerous public places that provide no real security (other than an occasional Paul Blart mall cop), New Jersey counsel, Angela Cai, denied that any security at all is necessary to be a "sensitive place." The state bans guns at public gatherings, zoos, parks, libraries and museums, bars and restaurants, and assorted other locations. Places where people congregate, she argued, suffice to make a place sensitive – exactly a criterion Bruen explicitly rejected. Even the "crowded place" argument gets dropped when gun bans at extensive wooded parks are defended.

At bottom, unmoored from comprehensive security, no limiting principle exists to what is a "sensitive place." And, the benefit to comprehensive security as the criteria for demonstrating that a location is a "sensitive place" is that it is easy to administer for judges. After all, judges literally live within the bubble of comprehensive security whenever they go to work: armed guards, metal detectors and limited (and locked) entry points to ensure bad guys with guns cannot sneak in. Furthermore, it is worth noting that where the Founders feared that churches were vulnerable to violent attacks, they did not declare them to be a "weapons free zone" but instead legally required Americans to bring their arms there.

Ms. Cai brought up the 1328 Statute of Northampton, but Bruen saw it as relevant only as reflected in Virginia's 1786 rendition providing that "no man, great nor small, [shall] go nor ride armed by night nor by day, in fairs or markets, or in other places, in terror of the Country." She sought to separate the terror element from the crime of going armed in fairs or markets – fairs and markets being today's supposed "crowded places" – but Bruen recognized no such separation. The Founders regulated the misuse of the public carry of firearms by banning carrying firearms in a manner to terrify the public; peaceable carry was for defensive purposes and was not restricted even in urban settings, as none other than Founder and criminal defense attorney John Adams noted in his defense of the British after the Boston Massacre. Adams conceded that the colonists had every right to carry arms in Boston for defensive purposes.

In a classic example of "fake news," Judge Chung asked counsel for Koons, Pete Patterson, about North Carolina's supposed 1792 statutory enactment, which was "exactly the same as Northampton." As Mr. Patterson correctly responded, "There was no 1792 North Carolina statute. That was in a private lawyer's collection of … the British laws he posited that were still in effect in North Carolina." And it even referenced "the King." I have previously written about how some judges have been duped by this "fake" 1792 NC statute, and have an article forthcoming on it in the Journal of Law & Civil Governance at Texas A&M. Instead, as I've explained in more detail, North Carolina enacted a law in 1741 and reenacted it in 1791 recognizing the offense of "go[ing] armed offensively," which is another way of stating that one cannot publicly carry arms "to the terror" of the people.

In her Rahimi concurrence, Justice Barrett rejected the assumption that "founding-era legislatures maximally exercised their power to regulate, thereby adopting a 'use it or lose it' view of legislative authority." But the text-history method still applied, and she warned against too high a level of generality when considering historical analogues. In response from a question from Judge Shwartz about legislative silence, Ms. Cai replied that little need existed at the Founding for expansive sensitive places, but the expiration of the patent for the Colt revolver in 1850 prompted more handgun production and consequent more interpersonal violence by the 1870s. That explained the passage of restrictions in Texas, Missouri, and Tennessee.

But as Judge Porter asked: "Why is that a new social problem that had never been contemplated before? Isn't that exactly the kind of thing that was addressed by the statute of Northampton going back 600 years?" Ms. Cai added nothing new to her argument. But it goes without saying that blunt instruments, edged weapons, spears, bows, tomahawks, and plenty of arms have been available over the centuries for both defensive and offensive use.

And it bears repeating, as Heller noted, that the Second Amendment protects modern arms that are in common use, and that if they are to be restricted, the burden falls on the state to show that they are not in common use.

As to the above three state laws cited by Ms. Cai, they were too little and too late. Mr. Patterson pointed out that "the Supreme Court in Espinoza said more than 30 state laws from the late 19th century cannot create an early American tradition." Like the 1870s laws cited in this case, the laws at issue in Espinoza, which were held to violate the Free Exercise Clause, were not rooted in the Founding.

That also raises the 1791 versus 1868 issue. Which prevails? Chief Judge Chagares asked Ms. Cai:

You argue in your brief, in various places, in particular your reply brief at page 18, that in the event of a clash between founding era and reconstruction era historical analogues, that the latter ought to control for purposes of our inquiry under Bruen. Doesn't Bruen tell us something different? … The opinion says on page 66, "Late 19th century evidence cannot provide much insight into the meaning of the Second Amendment when it contradicts earlier evidence."

Ms. Cai replied: "You will not find a single case that a plaintiff has cited from either the founding period or the antebellum period or reconstruction that says restrictions at sensitive places and … many jurisdictions adopted them was unconstitutional." Well, that's because there were virtually no such restrictions at the founding or antebellum periods, and there were only a handful during Reconstruction.

The fact is that the Founders were not silent, but spoke loudly, when they adopted the Second Amendment itself and also when they legislated to punish going armed in places of public congregation like fairs and markets in a manner to terrify others. The right peaceably to bear arms at every public place is the default rule, and the only exceptions are narrowly-defined, government-protected sensitive places. And it's the government's burden to demonstrate that those places are consistent with America's historical tradition of regulation.

The extent to which facial challenges may be brought to arms restrictions has been a controverted subject of late, with the Fourth Circuit rejecting a parks restriction in LaFave v. Fairfax County in which a cert petition is now pending (I'm counsel in the case). In Seigel (the companion case to Koons), in which challenges were made to parts, but not all, of certain sections of the law, Judge Freeman asked "what allows you to have a facial challenge to just a part of a statutory provision?" Counsel Erin Murphy explained that bans on carry at playgrounds and youth sporting events were being challenged, but "we are only challenging the provisions that are there to reach things that are not happening on school property." Heller itself exemplified that a facial challenge may be brought to a law (D.C.'s complete ban on handguns), even though some other law could apply to a specific person (e.g., a felon) or to "sensitive places" (such as D.C.-located courthouses).

Judge Chung asked why the $200 fee for a handgun carry permit could not be applied to a person with a conviction for harming someone. Ms. Murphy replied, "I've never understood facial challenge doctrine to mean that if you can come up with a completely different law the state could have written and shoehorn that in, then your facial challenge fails because the whole point of this law is to say, no, you have to pay the fee." This is correct. The government may not hypothesize about a non-existence statute that a legislature could have (but did not) actually enact in order to save an existing unconstitutionally-drafted statute. See Peter Patterson, Facial Confusion: Lower Court Misapplication of the Facial/As-Applied Distinction in Second Amendment Cases, Harvard JLPP (2025). The issue arose in part in the context of whether having to pay the fee creates irreparable harm for purposes of a preliminary injunction. Imagine whether it would be irreparable harm to impose a poll tax of $1.50 to vote (the Supreme Court said yes in Harper v. Virginia).

It will not be surprising if the Koons court delays a decision until after the Supreme Court resolves Wolford, which concerns Hawaii's ban on firearm possession on private property as applied to places open to the public. The Supreme Court is sure to give further guidance on how far states may go in restricting the places where the right to bear arms exists.

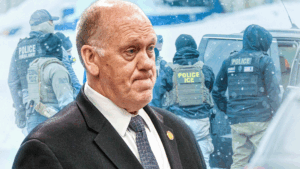

A combination of legal action and political resistance helped deal Trump a defeat.

Earlier today, Trump "border czar" Tom Homan announced that Operation Metro Surge - the massive deployment of some 3000 federal immigration enforcement officers to Minnesota - is about to end. Significantly, it is ending earlier than most expected, and without having achieved the stated goal of forcing Minnesota state and local governments to end their "sanctuary" policies restricting cooperation with federal immigration enforcement.

It seems likely that Trump gave up because the policy met with extensive resistance and has become highly unpopular. His public opinion approval ratings on immigration policy have plummeted. That setback for the administration occurred in large part because of a combination of legal and political resistance.

Courts ruled against the administration on some of its more blatantly illegal detentions, such as those targeting refugees. Federal Judge Katherine Menendez refused to grant a preliminary injunction in a Tenth Amendment suit filed by state and local governments, but made clear that the plaintiffs might well ultimately prevail. Meanwhile, a massive political mobilization helped draw attention to the administration's cruel, abusive, and illegal tactics, increasing public revulsion and opposition.

In a May 2025 article for The UnPopulist, I argued that effective resistance to Trump's many unjust and unconstitutional power grabs requires a combination of litigation and political action, exploiting synergies between the two. Litigation can help block unconstituitional policies, and highlight abuses. That can help stimulate public opposition and mobilization, which can in turn pave the way for more victories in court, as judges will often feel more able to rule against the administration if they believe they will have the backing of public and elite opinion. Judicial victories can then stimulate additional political mobilization, and so on. As noted in my particle, historical examples ranging from the Civil Rights Movement to struggles for constitutional property rights indicate this dynamic can be very effective.

Something like this dynamic seems to been at work in Minnesota. Abuses highlighted by court cases helped stimulate public opposition, and judges may be more willing to rule against abuses, given widespread public support. In particular, litigation likely helped more people realize that Trump's detention deportation efforts were not targeting criminals and the "worst of the worst," but instead primarily going after people who were living and working peacefully, contributing to their communities - including even many who were in the country legally, such as numerous refugees and asylum seekers. The ultimately successful litigation over the heartrending case of 5-year-old Liam Ramos and his family (who had an asylum application pending), was particularly notable in driving these points home.

These dynamics obviously not the only factors in the setback for Trump. But they helped. The shooting of two US citizens by federal agents were also significant. But the trend towards declining support for Trump's immigration agenda began well before that, with his approval rating on the issue beginning to slip by April of last year. Going forward, advocates for migrant rights and other related causes would do well to learn from the Minnesota experience, and from other examples compiled in my UnPopulist article.

Obviously, the setback for Trump here is unlikely to completely end this administration's often cruel and illegal immigration policies. Nor has it reversed all the massive harm done by Operation Metro Surge. As Judge Menendez noted in her ruling, "Operation Metro Surge has had…. profound and even heartbreaking, consequences on the State of Minnesota, the Twin Cities, and Minnesotans," including the killing of two citizens by federal agents, large-scale "racial profiling, excessive use of force, and other harmful actions," and "negative impacts…. in almost every arena of daily life." There also has been no accountability for the federal officials responsible for these outrages.

But the dual strategy of litigation and political action has at least mitigated the damage. And it can be used again in at least some situations going forward.

As noted in my UnPopulist article, this kind of strategy does have noteworthy limitations:

It is particularly important to recognize the limits of public attention and knowledge. Survey data shows most voters pay little attention to politics, and often don't know even basic information about government and public policy—including judicial decisions. This makes it hard to attract public attention to more than a few legal battles at any given time. That dynamic limits the number of situations where advocates can count on judicial decisions, even important ones with sympathetic facts, moving public opinion….

Some complex legal issues, moreover, are difficult or impossible to present to the public in a way that enables people to grasp their significance. That doesn't mean litigation in such cases is a bad idea. But it does mean it cannot rely on a boost from mobilizing public opinion.

In addition, while litigation efforts promoting popular results can help mobilize public opinion in support of a cause, litigation promoting unpopular ones can have the opposite effect….

Despite these constraints, utilizing synergies between litigation and political action can often be an effective strategy for curbing abuses of government power and strengthening constitutional protections. Minnesota is a notable additional case in point. We would do well to learn from it, as there are likely to be more opportunities to make use of the lesson.

UPDATE: I have made minor additions to this post.

An excerpt from Judge Richard Leon's long (and exclamation-point-filled) opinion today in Kelly v. Hegseth (D.D.C.):

United States Senator Mark Kelly, a retired naval officer, has been censured by Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth for voicing certain opinions on military actions and policy. In addition, he has been subjected to proceedings to possibly reduce his retirement rank and pay and threatened with criminal prosecution if he continues to speak out on these issues. Secretary Hegseth relies on the well-established doctrine that military servicemembers enjoy less vigorous First Amendment protections given the fundamental obligation for obedience and discipline in the armed forces. Unfortunately for Secretary Hegseth, no court has ever extended those principles to retired servicemembers, much less a retired servicemember serving in Congress and exercising oversight responsibility over the military. This Court will not be the first to do so! …

Defendants boldly argue that Senator Kelly's speech was unprotected [by the First Amendment], citing to a line of precedent establishing that First Amendment protections are more limited in the military context. See, e.g., Parker v. Levy (1974)…. Defendants rest their entire First Amendment defense on the argument that the more limited First Amendment protection for active-duty members of the military extends to a retired naval captain.

To be sure, while soldiers "are not excluded from" the First Amendment's coverage, "the different character of the military community and of the military mission requires a different application of those protections." From Parker onward, the Supreme Court has recognized that "[t]he fundamental necessity for obedience, and the consequent necessity for imposition of discipline, may render permissible within the military that which would be constitutionally impermissible outside it." Therefore, given the countervailing interests at stake in the line of duty, "speech by a member of the military that undermines the chain of command, and the obedience, order, and discipline it is designed to ensure, does not receive First Amendment protection."

However, the cases in this area uniformly involve active-duty servicemembers or speech on military bases. While retired servicemembers have an "ongoing duty to obey military orders" and may be recalled to active duty, Defendants have not identified a single case extending Parker's reasoning outside the context of active-duty soldiers.

From La Union del Pueblo Entero v. Abbott, decided today by Judge Edith Jones, joined by Judge Kurt Engelhardt and District Judge Robert Summerhays (W.D. La.):

The district court gave an interview to the Wall Street Journal explaining how he had used artificial intelligence as an adjunct to his work on some aspects of a case "involving Texas[ ] election law." Whether it was this case is uncertain. However, as one distinguished U.S. Senator [Grassley] has commented, AI "must not be a substitute for legal judgment," nor must the public perceive that federal judges outsource our judgment to AI tools.

Thanks to Michael Smith (Smith Appellate Law Firm) for the pointer.

What the collapses of two communist regimes teach us about the rule of law in the United States

I published my first piece in The Unpopulist yesterday, and it is accessible here.

In it I argue that the contrast between Czechoslovakia's peaceful Velvet Revolution and Romania's violent regime change offers vital lessons for Americans today about the importance of actively defending legal institutions and norms against authoritarian threats. Enjoy!

The Supreme Court heard oral argument in Louisiana v. Callais back on October 15. At the time, there was a broad consensus the Court would severely weaken, if not gut Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The only question was when the Court would rule. Depending on how quickly the opinion came out, the Louisiana legislature might be able to hold a special session to redistrict for the midterm.

Fast forward four months to the present, and there is no opinion in Callas. Indeed, the Court also hasn't decided the tariffs case, Slaughter, or anything else of substance yet.

Today, Rick Hasen has a post on the Election Law Blog, titled "A Justice Alito-Authored Majority Opinion in Callais Effectively Killing Off the Voting Rights Act Might Not Get 5 Votes; What Choices Do the Court's Conservatives Have?"

Rick explains that he has "now gone back and read Allen v. Milligan, and in particular Justice Alito's dissent." Rick thinks Justice Alito would write an opinion that "would doom most, if not all, Section 2 cases in the redistricting context." That was certainly how I read the oral argument four months ago. I didn't need to re-read a 2023 case to reach that conclusion.

Then Rick offers some fairly specific speculation about how Justice Alito might not get five votes for that sort of majority opinion.

I could easily see Justice Alito writing an opinion like this. The question is whether he could get a majority to endorse it. Here, counting noses, I'm not sure. This part of the opinion was joined only by Justice Gorsuch, not by Justice Thomas, who has taken the view that these cases should not be nonjusticiable, and not by Justice Barrett, who joined the other parts of Justice Thomas's dissent (but not Alito's) that sees Section 2 as unconstitutional if it means what the majority said it meant. Even if Thomas and Barrett signed on, could they get Roberts or Kavanaugh? That's not clear. The majority opinion written by Roberts, discussing what Alito wrote, says: "JUSTICE ALITO argues that "[t]he Gingles framework should be [re]interpreted" in light of changing methods in statutory interpretation. Post, at 10 (dissenting opinion). But as we have explained, Gingles effectuates the delicate legislative bargain that §2 embodies. And statutory stare decisis counsels strongly in favor of not "undo[ing] . . . the compromise that was reached between the House and Senate when §2 was amended in 1982." Brnovich, 594 U. S., at _ (slip op., at 22)." Kavanaugh in his separate opinion seemed to agree: "I agree with the Court that Alabama's redistricting plan violates §2 of the Voting Rights Act as interpreted in Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U. S. 30 (1986)."

I don't disagree with anything Rick wrote here. But all of this prognostication could have been made four months ago. The usual workflow is that people write about a case before it is argued, write about a case immediately after it is argued (before the conference), and then let the matter sit until the case is decided. That is, unless something prompts people to write about a pending case.

My ears perk up when people speculate about how a Supreme Court opinion is developing long after oral argument. Back in 2012, there were leaks from the Obamacare litigation. People on both sides of the case tried to sway the Justices one way or the other, as Chief Justice Roberts changed his vote. About a month after Bostock was argued, I wrote a post about a potential leak suggesting that Justice Gorsuch was going to vote with Justice Kagan. Shortly before Politico published the leaked opinion from Dobbs, I speculated that there was leak that the Chief Justice was trying to flip votes. And despite Chief Justice Roberts's NDA, leaks from the Count continue.

I'm not ready to speculate there was a leak in Callais, yet. Rick's post may just be an attempt to grapple with the fact that we still don't have a decision yet. It is certainly likely that a fractured majority opinion will take more time. But if there is another article, in close proximity, about the Justices' inability to form a five member bloc, I'll update my speculation.

Finally, Rick closes with this admonition:

It's possible that one or both of these Justices would throw out Gingles, perhaps citing constitutional avoidance. But it's just as likely given Kavanaugh's concurrence that he would vote to hold Section 2 unconstitutional.

That might make a majority in theory to overturn Section 2 as unconstitutional, but the Court would take a big political hit in an election year. Not sure that Kavanaugh and Alito would want to hurt the Republican Party further in the midterms.

I still believe that the Justices are trying to get the law right, and not trying to help one political party over the other. But we have seen this charge so many times. We heard it while the Affordable Care Act case was pending, while King v. Burwell was pending, while Dobbs was pending, while Trump v. United States was pending, and so on. We are always one year away from a general or midterm election. Is it the case that conservative judges can only do conservative things in odd-numbered years? If the conservatives on the Court wanted to help the Republican party in perpetuity, they would follow Justice Alito's lead. I am not at all convinced that any districts will be swayed in the slightest based on what the Supreme Court does here. Indeed, that is the point of partisan gerrymandering. If Section 2 is gone, swing districts that could be swayed by a Supreme Court decision will fade away. We should not be blind to the asymmetry that the Voting Rights Act helps only one side of the aisle.

Update: Rick replies that I am delusional.

In Doe v. Zeinalpoor-Movahed, decided May 7, 2024 by Judge John Tharp (N.D. Ill.) but just posted on Westlaw, plaintiff alleged that defendant sexually assaulted her:

At the time, the parties had been dating for several months. Both resided in Seattle, Washington, but had family in Chicago. They traveled to Chicago together, but spent some time separately visiting their families. They met up on December 28 at the home of Doe's parents, where they stayed the night, and on the 29th, they checked into a suite in an upscale Chicago hotel, which Doe's parents had paid for as a present to the couple. The following narrative of what ensued summarizes information submitted by the parties in support of their claims, with the principal disputes identified. {This case was originally filed in state court, and the state court permitted Doe to proceed anonymously. A motion to require Doe to proceed under her real name was pending when Doe's case was dismissed with prejudice.}

The record reflects that the Doe and Movahed were getting on well when they checked into the hotel; there is no evidence of any antecedent arguments or discord. After checking into the hotel, the parties shared a bottle of wine and had "consensual intercourse with enthusiastic and ongoing consent." (Doe's words.) Later, they walked to a nearby restaurant and met up with three friends of Movahed. Doe claims to have consumed three, or possibly four, beers, an Old Fashioned, and a shot of whiskey, and to have eaten a bowl of chili, while at the restaurant. Upon leaving the restaurant, Movahed invited his friends back to the hotel suite.

Doe says that she was inebriated and began to feel nauseous when the group drove from the restaurant back to the hotel. The parties dispute the degree of Doe's intoxication; Movahed notes that Doe was able to walk from the car to the hotel suite while Doe says that after returning to the hotel, she was so intoxicated that she next remembers only sitting in the bathroom vomiting into the toilet and later vomiting into an ice bucket while in bed, and on the sheets. For some portion of this time, Movahed and his friends were out on the hotel balcony drinking.

From Montana Supreme Court Justice James Jeremiah Shea's concurring opinion Tuesday in City of Kalispell v. Doman:

I concur fully with the Court's Opinion. I write separately only to highlight the exchange that occurred between Officer Minaglia and Doman, as set forth in the Court's Opinion. As the Court accurately notes, nobody disputed Doman's right to film the officers conducting the traffic stop—this included Officer Minaglia, whose first words to Doman upon exiting his car were: "Hey brother, I don't mind if you film … just do me a favor and kind of go a little bit a ways."

In response to Doman's statement that he was engaging in "First Amendment protected activity," Officer Minaglia stated "Right, I agree." As Doman repeatedly asserted his right to video the traffic stop, Officer Minaglia repeatedly agreed with him, stating: "I agree, just do me a favor and get out of where we're working, and you can totally film from right over here by this tree." It was only after Officer Minaglia's repeated requests that Doman move back from the scene while he recorded the traffic stop that Officer Minaglia arrested Doman for obstructing a peace officer.

Because Doman failed to preserve his constitutional arguments for appeal, this case ends up being only about whether or not the State presented sufficient evidence at trial to support Doman's conviction of the misdemeanor charge of obstructing a peace officer. That being the case, this Opinion likely will not warrant much, if any, notice from either the public or the press.

The pity in that is what will also be lost is an accounting of the professionalism that Officer Minaglia exhibited in this encounter. Regardless of whether you think that Doman was guilty of obstruction or even what you might think of the merits of his constitutional challenges—had they been preserved—you would be hard pressed to view the video of this encounter and conclude that it should have been handled any differently from a public engagement standpoint.

This bears noting because we are constantly inundated with images of violent and confrontational encounters between law enforcement and citizens who are attempting to record and document their interactions with law enforcement. The encounter in this case stands in stark contrast to those images. But when those are the only images you see, it's easy to think that is how these encounters typically unfold.

Having reviewed the record in countless cases that involved encounters between law enforcement and the public during my tenure on the Court, I would contend that Officer Minaglia's handling of this situation represents the norm rather than the exception, at least here in Montana, and stands as an example of how these encounters can be and are professionally handled. It is unfortunate that the video of this encounter will likely go the way of the Lost Ark because it doesn't make for good clickbait.

Here's what appears to be the video; the interaction with the police officer starts at around 1:45 into the 2:31 running time:

A district court concluded plaintiff had adequately alleged (it's all just allegations at this point) that the article included false and defamatory statements, but hadn't adequately alleged the statements were knowingly or recklessly false, and hadn't adequately alleged damages.

Excerpts from yesterday's decision by Judge Sheri Polster Chappell (M.D. Fla.) in Shriteh v. NYP Holdings, Inc. (with, as usual, some inevitable oversimplification of some of the legal points):

This is a defamation case. Plaintiff operates seventeen vape (or e-cigarette) retail stores in southwest Florida under the trademark name "the King of Vape." Christenson, writing for the New York Post, authored and published an article about Plaintiff titled, "Florida's Israel-hating 'King of Vape' Faces Bipartisan Crackdown on Sale of Illicit, Kid-Friendly Chinese E-cigs." The following is a summary of the article.

Plaintiff, a.k.a. the "King of Vape," is the co-founder of Safa Goods, one of the largest vape distributors in the United States. Safa Goods sells Chinese-produced vape brands in over a dozen "King of Vape" retail stores in southwest Florida. New York Attorney General Letitia James sued Safa Goods (among others) for illegal and fraudulent business practices that target underage e-cigarette users. United States Senator Ashley Moody also announced plans to protect children from illicit vapes. In Florida, Governor Ron DeSantis has cracked down on illicit vape sales. And the Food and Drug Administration is doing the same. All this government action, according to the article, demonstrates the "hotseat" in which Plaintiff sits "as lawmakers and officials try to throttle his distribution of illicit e-cigarettes manufactured in China."

According to the article, Plaintiff not only sells illicit vapes, but also has a "history of anti-Israel advocacy," which shows he is an Israel-hater. In February 1991, an Israeli court found that Plaintiff aided Hamas while working as a freelance reporter in the Gaza Strip. The Israeli judge found that Plaintiff "crossed the line in his work as a journalist" and "became an activist for a terror organization" by reporting information from a Hamas leaflet to readers. Defendants obtained this information from a 1991 New York Times article, which they hyperlinked in their article. Plaintiff also authored a 2003 book Beyond Intifada: Narratives of Freedom Fighters in the Gaza Strip, which covered the uprising of Palestinians against Israel beginning in 1987. And Plaintiff's relative (and director of Safa Goods) previously worked at United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees. The United States ceased all funding to this organization because some of its employees helped Hamas conduct the October 7, 2023, attack that killed 1,200 people.

After Plaintiff complained about the article, Defendants published a revised version titled, "Florida's 'King of Vape' Faces Bipartisan Crackdown on Family's Sale of Kid-Friendly Chinese E-cigs." However, the revised article still [allegedly] includes defamatory statements.

Plaintiff sued for libel, claiming these statements were "materially false" and defamatory:

- Plaintiff was the cofounder of Safa Goods;

- Plaintiff is involved in a lawsuit filed by New York Attorney General Letitia James;

- Plaintiff sells illicit goods to minors;

- Plaintiff is an "Israel hater" with a history of anti-Israel advocacy; and

- An Israeli court ruled that Plaintiff was a supporter of the terrorist organization, Hamas.

Relatedly, "Although not alleged to be false, Plaintiff also objects to the article's statement that Plaintiff's relative previously worked at an organization with employees who helped Hamas conduct the October 7, 2023, attack. He alleges Defendants included this statement 'in a transparent attempt to link [Plaintiff] with terrorism and further tarnish his reputation.'"

The court concluded that plaintiff was a public figure:

From Roe v. Gowl, decided yesterday by Judge Jesse Furman (S.D.N.Y.):

The Court previously ordered Plaintiff, who is currently proceeding without counsel and has been temporarily granted leave to proceed under the pseudonym "Jane Doe," to either consent to electronic service via ECF or move to participate as an ECF filer no later than February 10, 2026. On that date, the Court received a communication from Plaintiff, attached here, indicating that she had been advised that she could not create a PACER account under the pseudonym "Jane Doe" and asking the Court for guidance.

The undersigned spoke with members of the Clerk's Office, who explained that creating a PACER or ECF account in the name "Jane Doe" is not feasible because of the volume of "Jane Does" in the ECF system. To resolve this issue, permit Plaintiff to maintain her anonymity (as long as she is permitted to proceed pseudonymously), and ensure that Plaintiff receives filings in a timely fashion as long as she is proceeding without counsel, the Court will change Plaintiff's pseudonym to "Marcia Roe." Plaintiff should create a PACER account using the name "Marcia Roe" for the purposes of this litigation. Plaintiff should also create a new email address using that name to open that PACER account….

This reminded me of my broader concerns with the overuse of Doe (and for that matter Roe), which led me to publish an article in Judicature called "If Pseudonyms, Then What Kind?" You can read the PDF here and the text here; here are the opening sections:

[* * *]

Writers may have their noms de plume; revolutionaries may have noms de guerre. Here, though, we will speak of (to coin a phrase) the noms de litige, and ask: When pseudonymous litigation is allowed, what sorts of pseudonyms should be used? In particular, how can we avoid dozens of Doe v. Doe precedents or Doe v. University of __, all different yet identically named? This piece discusses some approaches to achieving the twin goals of pseudonyms: protecting privacy and avoiding confusion.

Courts generally disfavor pseudonymous litigation, but sometimes allow it.1 Indeed, they sometimes themselves pseudonymize cases for publication, even when the party names remain in the court records.2 Both courts and parties also sometimes pseudonymize the names of nonlitigant witnesses and victims. But what kinds of pseudonyms should be preferred? There are many options, including:

(I focus here on pseudonyms chosen for the purpose of litigation; when parties already have well-established pseudonyms, for instance as authors, there may be reason to retain them, assuming that such pseudonymity in litigation is found to be allowed.18)

Each option, unsurprisingly, has its strengths and weaknesses.

2/12/1965: Justice Brett Kavanaugh's birthday.

What’s on your mind?

It was notable that the GOP members and witnesses made little effort to actually defend the legislation in question.

Yesterday, I testified against the proposed "Preserving a Sharia-Free America Act" at a hearing before the US House of Representatives Judiciary Committee's Subcommittee on the Constitution and Limited Government. This proposed legislation would bar or deport virtually all non-citizen Muslims from the United States by mandating that "Any alien in the United States found to be an adherent of Sharia law by the Secretary of State, Secretary of Homeland Security, or Attorney General shall have any immigration benefit, immigration relief, or visa revoked, be considered inadmissible or deportable, and shall be removed from the United States."

My written testimony is available here. In it, I explained why the proposed law violates the Free Exercise and Free Speech clauses of the First Amendment, and why - if enacted and upheld by the courts - it would set a dangerous precedent, cause great harm to many thousands of innocent people, and damage US national security by giving a propaganda victory to radical Islamist terrorists. The other witnesses' written testimony is available here.

I embed the video of the oral testimony and hearing below. The hearing featured lots of political grandstanding, as is perhaps to be expected. So I can well understand if some readers decide watching the whole thing isn't worth their time. For those interested, my own opening statement runs from about 1:03 to 1:08:

Notably, the GOP members on the Subcommittee and the other three witnesses (all called by the Republicans; the minority party is allowed only one witness, in this case me) mostly didn't even try to defend proposed bill. Instead, they focused on various issues with Sharia law that - even if valid - would not require mass deportation or exclusion of migrants to address.

I won't try to go over the testimony of the other three witnesses in detail. Many of the concerns they raised were hyperbolic, often to the point of ridiculousness. No, there is no real threat that Sharia law is somehow going to take over the US legal system or that of the state of Texas (the focus of much of the testimony). And it is no grave threat to American values if some Muslims plan to establish a private compound where they live in accordance with their religious laws, especially since it turns out the compound in question will not actually enforce Sharia law on residents. Other religious groups do similar things all the time.

On the other hand, there may be some merit to Stephen Gelé's concerns that US courts sometimes enforce judgments issued by Sharia courts in Muslim dictatorships, in cases where they should not, because it would have harmful or illiberal consequences (e.g. - child custody rulings). The solution to such problems, however, is not to deport Muslim immigrants, but to alter the relevant legal rules on comity and conflict of laws. And, in fairness, Gelé's testimony did not recommend deportation and exclusion as a fix. If Texas courts are giving too much credence to some types of foreign court decisions, the GOP-dominated Texas state legislature can easily fix that problem!

Finally, the opposing witnesses and others who fear the supposed spread of Sharia law and the impact of Muslim immigrants often act as if Islam and Sharia are a single, illiberal monolith, irredeemably hostile to liberal values. In reality, as noted in my own testimony, there is widespread internal disagreement among Muslims about what their religion entails, as is also true of Christians and Jews. Most Muslim immigrants in the US are not trying to impose Sharia on non-Muslims, or establish some kind of Islamic theocracy. Indeed, many are themselves refugees from the oppression of radical Islamist dictatorships, such as those in Iran and Afghanistan.

My Cato Institute colleague Mustafa Akyol - a prominent expert on Islamic political thought - makes some additional relevant points on the diversity of Muslim thought in a recent article.

Some Muslims do indeed have awful, reprehensible beliefs on various issues. But there are lots of ways to address any danger that poses, without resorting to censorship, discrimination on the basis of religion, mass deportation, and other unconstitutional and repressive policies. The most obvious solution is to simply enforce the First Amendment's prohibitions on the establishment of religion, and persecution and discrimination on the basis of religious belief.

This was the third time I have testified in Congress. The other two times were at the invitation of Senate Republicans (see here and here). The issues at the three hearings were very different. But in each case, I tried to defend limits on government power that are essential to protecting individual rights to life, liberty, and property. I doubt my testimony had any great impact. But perhaps it made a small difference at the margin.

Now out in the Harvard Law Review.

I was very pleased that the new issue of the Harvard Law Review includes a book review of my 2025 book, The Digital Fourth Amendment. The review, by Jennifer Granick of the ACLU, is here: Fourth Amendment Equilibrium Adjustment in an Age of Technological Upheaval.

If you want to buy the book, you can get it here. If you want to listen to the first hour of the audiobook for free, you can listen that here (the book starts 75 seconds in, after an introduction by the audio book company).

The Environmental Protection Agency is reportedly prepared to rescind the "endangerment finding" that underpins the regulation of greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act.

Tomorrow the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is expected to release its final rule rescinding the "endangerment finding" for greenhouse gases. By taking this step, the Trump Administration is hoping to undercut the federal regulation of greenhouse gases and deprive the EPA of any authority to adopt such rules under the Clean Air Act.

I am on record arguing that this is a risky move. As a legal matter, attempting to undo the endangerment finding is not as simple or straightforward as many political commentators seem to think. The rule will immediately be subject to legal challenge, initially in the U.S Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, which is not the most friendly venue for aggressive deregulatory moves. As the New York Times reported, the Administration is nonetheless hoping that it can get this issue before the Supreme Court before the end of the Trump Administration, lest a new administration undercuts the defense of the rule.

It is hard to handicap any prospective legal challenge to the final rule rescinding the endangerment finding until it is released, as much will depend on the specific strategy the EPA has adopted, and how well that strategy is executed.

For background on the legal issues and what may be in store, here are some of my posts on the subject:

More to come!

Help Reason push back with more of the fact-based reporting we do best. Your support means more reporters, more investigations, and more coverage.

Make a donation today! No thanks

Every dollar I give helps to fund more journalists, more videos, and more amazing stories that celebrate liberty.

Yes! I want to put my money where your mouth is! Not interested

So much of the media tries telling you what to think. Support journalism that helps you to think for yourself.

I’ll donate to Reason right now! No thanks

Push back against misleading media lies and bad ideas. Support Reason’s journalism today.

My donation today will help Reason push back! Not today

Back journalism committed to transparency, independence, and intellectual honesty.

Yes, I’ll donate to Reason today! No thanks

Support journalism that challenges central planning, big government overreach, and creeping socialism.

Yes, I’ll support Reason today! No thanks

Support journalism that exposes bad economics, failed policies, and threats to open markets.

Yes, I’ll donate to Reason today! No thanks

Back independent media that examines the real-world consequences of socialist policies.

Yes, I’ll donate to Reason today! No thanks

Support journalism that challenges government overreach with rational analysis and clear reasoning.

Yes, I’ll donate to Reason today! No thanks

Support journalism that challenges centralized power and defends individual liberty.

Yes, I’ll donate to Reason today! No thanks

Your support helps expose the real-world costs of socialist policy proposals—and highlight better alternatives.

Yes, I’ll donate to Reason today! No thanks

Donate today to fuel reporting that exposes the real costs of heavy-handed government.

Yes, I’ll donate to Reason today! No thanks

Show Comments (0)