Refer to the README for the details.

GestureBot

A mobile robot that responds to human gestures, facial expressions using real-time pose estimation and gesture recognition & intuitive HRI

A mobile robot that responds to human gestures, facial expressions using real-time pose estimation and gesture recognition & intuitive HRI

To make the experience fit your profile, pick a username and tell us what interests you.

We found and based on your interests.

Refer to the README for the details.

When your robot becomes your shadow – implementing intelligent person following with object detection and ROS 2

Imagine a robot that follows you around like a loyal companion, maintaining the perfect distance whether you're walking through a warehouse, giving a facility tour, or need hands-free assistance. While gesture and pose control are great for direct commands, sometimes you want your robot to simply tag along autonomously. That's exactly what we've built into GestureBot – a standalone person following system that transforms any detected person into a moving target for smooth, intelligent pursuit.

Person following robots aren't just cool demos – they solve real problems. Consider a hospital robot carrying supplies that needs to follow a nurse through rounds, a security robot accompanying a guard on patrol, or a service robot helping someone navigate a large facility. In these scenarios, constant manual control becomes tedious and impractical.

The key insight is that following behavior should be completely autonomous once activated. No gestures, no poses, no commands – just intelligent tracking that maintains appropriate distance while handling the inevitable challenges of real-world environments: people walking behind obstacles, multiple individuals in the scene, varying lighting conditions, and the need for smooth, non-jerky motion that won't startle or annoy.

Rather than building a specialized person tracking system from scratch, we cleverly repurpose GestureBot's existing object detection capabilities. The system already runs MediaPipe's EfficientDet model at 5 FPS, detecting 80 different object classes including people with confidence scores and precise bounding boxes.

This architectural decision provides several advantages: proven stability, existing performance optimizations, and the ability to simultaneously track people and obstacles. The object detection system publishes to /vision/objects, providing a stream of detected people that our following controller can consume.

# Object detection provides person detections like this:

DetectedObject {

class_name: "person"

confidence: 0.76

bbox_x: 145 # Top-left corner

bbox_y: 89

bbox_width: 312 # Bounding box dimensions

bbox_height: 387

}The person following controller subscribes to this stream and implements sophisticated logic to select, track, and follow the most appropriate person in the scene.

When multiple people appear in the camera view, the system needs to intelligently choose who to follow. Our selection algorithm uses a weighted scoring system that considers three key factors:

Size Score (40% weight): Larger bounding boxes typically indicate closer people or those more prominently positioned in the scene. This naturally biases toward the person most likely intended as the target.

Center Score (30% weight): People closer to the image center are preferred, following the reasonable assumption that users position themselves centrally when activating following mode.

Confidence Score (30% weight): Higher detection confidence indicates more reliable tracking, reducing the chance of following false positives or poorly detected individuals.

def select_initial_target(self, people):

scored_people = []

for person in people:

# Normalize bounding box to 0-1 coordinates

size_score = (person.bbox_width * person.bbox_height) / (640 * 480)

center_x = (person.bbox_x + person.bbox_width/2) / 640

center_score = 1.0 - abs(center_x - 0.5) * 2

total_score = (size_score * 0.4 +

center_score * 0.3 +

person.confidence * 0.3)

scored_people.append((person, total_score))

return max(scored_people, key=lambda x: x[1])[0]Once a target is selected, the system maintains tracking continuity by matching people across frames based on position prediction, preventing erratic switching between similar individuals.

When hand gestures aren't enough, your whole body becomes the remote control

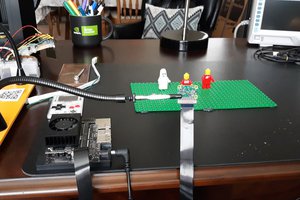

We've all been there – trying to control a robot with hand gestures while your hands are full, wearing gloves, or when lighting conditions make finger detection unreliable. What if your robot could understand your intentions through simple body poses instead? That's exactly what we've implemented in the latest iteration of GestureBot, a Raspberry Pi 5-powered robot that now responds to four distinct body poses for intuitive navigation control.

While hand gesture recognition is impressive, it has practical limitations. Gestures require clear hand visibility, specific lighting conditions, and can be ambiguous when multiple people are present. Body poses, on the other hand, are larger, more distinctive, and work reliably even when hands are obscured or busy with other tasks.

Consider a warehouse worker guiding a robot while carrying boxes, or a surgeon directing a medical robot while maintaining sterile conditions. Full-body pose detection opens up robotics applications where traditional gesture control falls short.

At the heart of our system lies Google's MediaPipe Pose Landmarker, which provides real-time detection of 33 body landmarks covering the entire human skeleton – from head to toe. Running on a Raspberry Pi 5 with 8GB RAM and a Pi Camera Module 3, we achieve stable 3-7 FPS pose detection at 640x480 resolution.

The MediaPipe model excels at tracking key body points including shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, and the torso center. What makes this particularly powerful for robotics is the consistency of landmark detection even with partial occlusion or varying lighting conditions.

# Core MediaPipe configuration optimized for Pi 5

pose_landmarker_options = {

'base_options': BaseOptions(model_asset_path='pose_landmarker.task'),

'running_mode': VisionRunningMode.LIVE_STREAM,

'num_poses': 2, # Track up to 2 people

'min_pose_detection_confidence': 0.5,

'min_pose_presence_confidence': 0.5,

'min_tracking_confidence': 0.5

}After experimenting with complex pose vocabularies, we settled on four reliable poses that provide comprehensive robot control:

🙌 Arms Raised (Forward Motion): Both arms extended upward above shoulder level triggers forward movement at 0.3 m/s. This pose is unmistakable and feels natural for "go forward."

👈 Pointing Left (Turn Left): Left arm extended horizontally while right arm remains down commands a left turn at 0.8 rad/s. The asymmetry makes this pose highly distinctive.

👉 Pointing Right (Turn Right): Mirror of the left turn – right arm extended horizontally triggers rightward rotation.

🤸 T-Pose (Emergency Stop): Both arms extended horizontally creates the universal "stop" signal, immediately halting all robot motion.

The pose classification algorithm analyzes shoulder and wrist positions relative to the torso center, using angle calculations and position thresholds to distinguish between poses:

def classify_pose(self, landmarks):

# Extract key landmarks

left_shoulder = landmarks[11]

right_shoulder = landmarks[12]

left_wrist = landmarks[15]

right_wrist = landmarks[16]

# Calculate arm angles relative to shoulders

left_arm_angle = self.calculate_arm_angle(left_shoulder, left_wrist)

right_arm_angle = self.calculate_arm_angle(right_shoulder, right_wrist)

# Classify based on arm positions

if left_arm_angle > 60 and right_arm_angle > 60:

return "arms_raised"

elif abs(left_arm_angle) < 30 and abs(right_arm_angle) < 30:

return "t_pose"

# ... additional classification logicThe system architecture follows a clean pipeline: pose detection → classification → navigation commands → smooth motion control. Built on ROS 2 Jazzy, the implementation uses three main components:

Pose Detection Node: Processes camera frames through MediaPipe,...

Read more »Gesture-controlled robotics represents a compelling intersection of computer vision, human-robot interaction, and real-time motion control. I developed GestureBot as a comprehensive system that translates hand gestures into precise robot movements, addressing the unique challenges of responsive detection, mechanical stability, and modular architecture design.

The project tackles several technical challenges inherent in gesture-controlled navigation: achieving sub-second response times while maintaining detection stability, preventing mechanical instability in tall robot form factors through acceleration limiting, and creating a modular architecture that supports future multi-modal integration. My implementation demonstrates how MediaPipe's gesture recognition capabilities can be effectively integrated with ROS2 navigation systems to create a responsive, stable, and extensible robot control platform.

I designed GestureBot with a modular architecture that separates gesture detection from motion control, enabling flexible deployment and future expansion. The system consists of two primary components connected through ROS2 topics:

Gesture Recognition Module: Handles camera input and MediaPipe-based gesture detection, publishing stable gesture results to /vision/gestures. This module operates independently and can function without the motion control system for testing and development.

Navigation Bridge Module: Subscribes to gesture detection results and converts them into smooth robot motion commands published to /cmd_vel. This separation allows the navigation bridge to potentially receive input from multiple detection sources in future implementations.

Camera Input → MediaPipe Processing → Gesture Stability Filtering → /vision/gestures

↓

/cmd_vel ← Acceleration Limiting ← Velocity Smoothing ← Motion Mapping ←──┘

The modular design enables independent operation of components. I can run gesture detection without motion control for development, or use external gesture sources with the navigation bridge. This architecture prepares the system for Phase 4 multi-modal integration where object detection and pose estimation will feed into the same navigation bridge.

I implemented separate launch files for each component:

gesture_recognition.launch.py: Camera and gesture detection onlygesture_navigation_bridge.launch.py: Motion control and navigation logicmulti_modal_navigation.launch.py: Integrated multi-modal systemThis separation provides deployment flexibility and simplifies parameter management for different robot configurations.

I integrated MediaPipe's gesture recognition model using a controller-based architecture that handles the MediaPipe lifecycle independently from ROS2 infrastructure. The implementation uses MediaPipe's LIVE_STREAM mode with asynchronous processing for optimal performance:

class GestureRecognitionController:

def __init__(self, model_path: str, confidence_threshold: float, max_hands: int, result_callback):

self.model_path = model_path

self.confidence_threshold = confidence_threshold

self.max_hands = max_hands

self.result_callback = result_callback

# Initialize MediaPipe gesture recognizer

base_options = python.BaseOptions(model_asset_path=self.model_path)

options = vision.GestureRecognizerOptions(

base_options=base_options,

running_mode=vision.RunningMode.LIVE_STREAM,

result_callback=self._mediapipe_callback,

min_hand_detection_confidence=self.confidence_threshold,

min_hand_presence_confidence=self.confidence_threshold,

min_tracking_confidence=self.confidence_threshold,

num_hands=self.max_hands

)

self.recognizer = vision.GestureRecognizer.create_from_options(options)

The controller processes camera frames asynchronously and extracts gesture classifications, hand landmarks, and handedness information....

Read more »Most robotics vision systems treat humans as simple bounding boxes – "person detected, avoid obstacle." But humans are dynamic, expressive, and predictable if you know how to read body language. A person leaning forward might be about to walk into the robot's path. Someone pointing could be giving directional commands. Arms raised might signal "stop."

I needed a system that could:

The heart of my implementation is a modular ROS 2 node that wraps MediaPipe's PoseLandmarker model. I chose a composition pattern to keep the ROS infrastructure separate from the MediaPipe processing logic:

class PoseDetectionNode(MediaPipeBaseNode, MediaPipeCallbackMixin):

def __init__(self, **kwargs):

MediaPipeCallbackMixin.__init__(self)

super().__init__(

node_name='pose_detection_node',

**kwargs

)

# Initialize the pose detection controller

self.controller = PoseDetectionController(

model_path=self.model_path,

confidence_threshold=self.confidence_threshold,

max_poses=self.max_poses,

logger=self.get_logger()

)The PoseDetectionController handles all MediaPipe-specific operations:

class PoseDetectionController:

def __init__(self, model_path: str, confidence_threshold: float, max_poses: int, logger):

self.logger = logger

# Configure MediaPipe options

base_options = python.BaseOptions(model_asset_path=model_path)

options = vision.PoseLandmarkerOptions(

base_options=base_options,

running_mode=vision.RunningMode.LIVE_STREAM,

num_poses=max_poses,

min_pose_detection_confidence=confidence_threshold,

min_pose_presence_confidence=confidence_threshold,

min_tracking_confidence=confidence_threshold,

result_callback=self._pose_callback

)

self._landmarker = vision.PoseLandmarker.create_from_options(options)MediaPipe's pose model detects 33 landmarks covering the entire human body:

Each landmark provides normalized (x, y) coordinates plus a visibility score, giving rich information about human pose and orientation.

One of the trickier aspects was properly handling MediaPipe's asynchronous LIVE_STREAM mode. The pose detection happens in a separate thread, with results delivered via callback:

def _pose_callback(self, result: vision.PoseLandmarkerResult,

output_image: mp.Image, timestamp_ms: int):

"""Handle pose detection results from MediaPipe."""

try:

# Convert MediaPipe timestamp to ROS time

ros_timestamp = self._convert_timestamp(timestamp_ms)

# Process pose landmarks

pose_msg = PoseLandmarks()

pose_msg.header.stamp = ros_timestamp

pose_msg.header.frame_id = 'camera_frame'

if result.pose_landmarks:

pose_msg.num_poses = len(result.pose_landmarks)

# Handle MediaPipe's pose landmark structure variations

for pose_landmarks in result.pose_landmarks:

try:

# MediaPipe structure can vary between versions

if hasattr(pose_landmarks, '__iter__') and not hasattr(pose_landmarks, 'landmark'):

landmarks = pose_landmarks # Direct list access

else:

landmarks = pose_landmarks.landmark # Attribute access

for landmark in landmarks:

point = Point()

point.x = landmark.x

point.y = landmark.y

point.z = landmark.z

pose_msg.landmarks.append(point)

except Exception as e:

self.logger.warn(f'Pose landmark processing error: {e}')

continue

# Publish results

self.pose_publisher.publish(pose_msg)

except Exception as e:

self.logger.error(f'Pose callback error: {e}')\Let me be honest about performance – this isn't going...

Read more »System Overview and Architecture

The GestureBot gesture recognition system is built on a modular ROS 2 architecture that combines MediaPipe's powerful computer vision capabilities with efficient real-time processing optimized for embedded systems. The core system processes camera input at 15 FPS, detects hand gestures with 21-point landmark tracking, and translates recognized gestures into navigation commands for autonomous robot control.

Through extensive testing and optimization, I've achieved the following performance characteristics on Raspberry Pi 5:

The foundation of the gesture recognition system is a robust integration between MediaPipe's gesture recognition capabilities and ROS 2's distributed computing framework. I implemented this using a callback-based architecture that maximizes performance while maintaining system responsiveness.

The system consists of several key components working in concert:

GestureRecognitionNode: The primary ROS 2 node that inherits from MediaPipeBaseNode, providing standardized MediaPipe integration patterns across the vision system.

MediaPipe Gesture Recognizer: Utilizes the pre-trained gesture_recognizer.task model for real-time gesture classification with confidence scoring.

Unified Image Viewer: A multi-topic display system that can simultaneously show gesture recognition results, hand landmarks, and performance metrics.

I implemented the MediaPipe integration using an asynchronous callback pattern that ensures optimal performance:

def initialize_mediapipe(self) -> bool:

"""Initialize MediaPipe gesture recognizer with callback processing."""

try:

# Configure gesture recognizer options

options = mp_vis.GestureRecognizerOptions(

base_options=mp_py.BaseOptions(model_asset_path=self.model_path),

running_mode=mp_vis.RunningMode.LIVE_STREAM,

result_callback=self._process_callback_results,

num_hands=self.max_hands,

min_hand_detection_confidence=self.confidence_threshold,

min_hand_presence_confidence=self.confidence_threshold,

min_tracking_confidence=self.confidence_threshold

)

self.gesture_recognizer = mp_vis.GestureRecognizer.create_from_options(options)

return True

except Exception as e:

self.get_logger().error(f"Failed to initialize MediaPipe: {e}")

return FalseThis approach uses MediaPipe's LIVE_STREAM mode with detect_async() for optimal performance, avoiding blocking operations in the main processing thread.

The gesture recognition system implements comprehensive 21-point hand landmark tracking, providing detailed skeletal information for each detected hand. This landmark data serves dual purposes: gesture classification input and visual feedback for system debugging.

MediaPipe's hand landmark model provides 21 key points representing the complete hand structure:

I implemented a comprehensive visualization system that draws both individual landmarks and connecting skeleton lines:

def draw_hand_landmarks(self, image: np.ndarray, hand_landmarks_list) -> None:

"""Draw complete hand landmarks with skeleton connections."""

try:

if not hand_landmarks_list:

return

height, width = image.shape[:2]

for hand_index, hand_landmarks in enumerate(hand_landmarks_list):

...

Read more »

When developing the GestureBot vision system, I encountered a common challenge in robotics computer vision: balancing performance with visualization flexibility. While MediaPipe provides excellent object detection capabilities, its built-in annotation system proved limiting for our specific visualization requirements. This post details how I implemented a custom manual annotation system using OpenCV primitives while maintaining MediaPipe's high-performance LIVE_STREAM processing mode.

MediaPipe's object detection framework excels at inference performance, but its visualization capabilities presented several limitations for our robotics application:

LIVE_STREAM mode doesn't always provide reliable output_image resultsFor GestureBot's vision system, I needed:

The solution involved decoupling MediaPipe's inference engine from the visualization layer, creating a custom annotation system that operates on the original RGB frames.

# High-level flow

RGB Frame → MediaPipe Detection (LIVE_STREAM) → Manual Annotation → ROS Publishing The key insight was to preserve MediaPipe's asynchronous detect_async() processing while applying custom annotations to the original RGB frames, rather than relying on MediaPipe's output_image.

def draw_manual_annotations(self, image: np.ndarray, detections) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Manually draw bounding boxes, labels, and confidence scores using OpenCV.

Args:

image: RGB image array (H, W, 3)

detections: MediaPipe detection results

Returns:

Annotated RGB image array

"""

if not detections:

return image.copy()

annotated_image = image.copy()

height, width = image.shape[:2]

for detection in detections:

# Get bounding box coordinates

bbox = detection.bounding_box

x_min = int(bbox.origin_x)

y_min = int(bbox.origin_y)

x_max = int(bbox.origin_x + bbox.width)

y_max = int(bbox.origin_y + bbox.height)

# Ensure coordinates are within image bounds

x_min = max(0, min(x_min, width - 1))

y_min = max(0, min(y_min, height - 1))

x_max = max(0, min(x_max, width - 1))

y_max = max(0, min(y_max, height - 1))

# Get the best category (highest confidence)

if detection.categories:

best_category = max(detection.categories, key=lambda c: c.score if c.score else 0)

class_name = best_category.category_name or 'unknown'

confidence = best_category.score or 0.0

# Color-coded boxes based on confidence levels

if confidence >= 0.7:

color = (0, 255, 0) # Green for high confidence (RGB)

elif confidence >= 0.5:

color = (255, 255, 0) # Yellow for medium confidence (RGB)

else:

color = (255, 0, 0) # Red for low confidence (RGB)

# Draw bounding box rectangle

cv2.rectangle(annotated_image, (x_min, y_min), (x_max, y_max), color, 2)

# Prepare label text with confidence percentage

confidence_percent = int(confidence * 100)

label = f"{class_name}: {confidence_percent}%"

# Calculate text size for background rectangle

font = cv2.FONT_HERSHEY_SIMPLEX

font_scale = 0.6

thickness = 2

(text_width, text_height), baseline = cv2.getTextSize(label, font, font_scale, thickness)

# Position text above bounding box, or below if not...

Read more »

I recently completed a comprehensive performance optimization project for a ROS 2-based object detection pipeline using MediaPipe and OpenCV. The system processes camera frames for real-time object detection in robotics applications, but initial performance analysis revealed significant bottlenecks that were limiting throughput and consuming excessive CPU resources.

The object detection pipeline consists of three main stages:

Through systematic measurement and targeted optimization, I achieved a 68.7% reduction in total pipeline processing time, from 8.65ms to 2.71ms per frame, while maintaining full functionality and improving system stability.

Before implementing any optimizations, I established a comprehensive performance measurement system to ensure accurate, statistically reliable data collection. The measurement infrastructure includes:

PipelineTimer Class: High-precision timing using time.perf_counter() for microsecond-level accuracy:

class PipelineTimer:

def __init__(self):

self.stage_times = {}

self.start_time = None

def start_stage(self, stage_name: str):

self.stage_times[stage_name] = time.perf_counter()

def end_stage(self, stage_name: str) -> float:

if stage_name in self.stage_times:

duration = time.perf_counter() - self.stage_times[stage_name]

return duration * 1000 # Convert to milliseconds

return 0.0PerformanceStats Class: Aggregates timing data over 5-second periods and publishes metrics to ROS topics:

class PerformanceStats:

def __init__(self):

self.period_start_time = time.perf_counter()

self.frames_processed = 0

self.total_preprocessing_time = 0.0

self.total_mediapipe_time = 0.0

self.total_postprocessing_time = 0.0

self.period_duration = 5.0 # secondsStatistical Methodology: I used 30-second test periods with multiple measurement intervals to ensure statistical confidence. Each test collected 5-6 data points, allowing calculation of mean performance metrics and variance analysis.

Using YUYV camera format with full annotated image processing enabled, the baseline performance measurements revealed:

>td ###Total Pipeline Time

| Metric | Average Time | |

|---|---|---|

| 8.65ms | 100>#/td### | |

| Preprocessing Time | 1.22ms | 14>#/td### |

| MediaPipe Inference | 2.13ms | 25>#/td### |

| Postprocessing Time | 5.30ms | 61>#/td### |

| Effective FPS | 2.28 | - |

The baseline analysis immediately identified postprocessing as the primary bottleneck, consuming 61% of total pipeline time. This stage includes MediaPipe result conversion, RGB→BGR color conversion, and ROS Image message creation for annotated output.

The postprocessing bottleneck was caused by unconditional generation of annotated images, even when no ROS subscribers were listening to the /vision/objects/annotated topic. This resulted in expensive memory operations and color conversions being performed unnecessarily.

I implemented a subscriber count check to conditionally skip annotated image processing when no subscribers are present:

def publish_results(self, results: Dict, timestamp: float) -> None:

"""Publish object detection results and optionally annotated images."""

try:

# Always publish detection results

msg = MessageConverter.detection_results_to_ros(results, timestamp)

self.detections_publisher.publish(msg)

# Conditional annotated image publishing

if (self.annotated_image_publisher is not None and

'output_image' in results and

results['output_image'] is not None):

# Optimization: Skip expensive postprocessing if no subscribers

subscriber_count = self.annotated_image_publisher.get_subscription_count()

if subscriber_count == 0:

self.log_buffered_event(

...

Read more »

When building real-time computer vision systems with ROS 2, diagnostic logging becomes critical for debugging complex processing pipelines. However, poorly designed logging systems can create more confusion than clarity. I recently refactored the buffered logging system in my GestureBot object detection node, transforming a confusing, duplicated implementation into a clean, reusable architecture that other robotics developers can learn from.

The original buffered logging system suffered from several fundamental issues that made it difficult to use and maintain:

Confusing Terminology: The system used "production mode" and "debug mode" labels that didn't reflect actual behavior. "Production mode" suggested it was only for deployment, while "debug mode" implied it was only for development. In reality, both modes had legitimate use cases across different scenarios.

Inconsistent Timer Behavior: The system used a 120-second timer for "debug mode" and a 10-second timer for "production mode." This inconsistency made it difficult to predict when diagnostic information would be available.

Code Duplication: The BufferedLogger class was implemented directly in

object_detection_node.py

, making it impossible for other vision nodes (gesture detection, face detection) to reuse the same logging infrastructure.

Unclear Parameters: Launch file parameters like enable_debug_buffer obscured what the system actually did, requiring developers to read implementation details to understand behavior.

I redesigned the system around three core principles: clear behavioral naming, consistent timing, and reusable architecture.

The new system uses descriptive names that immediately communicate what each mode does:

# Before: Confusing mode names

'mode': 'debug' if self.debug_mode else 'production'

# After: Behavior-based naming

'mode': 'unlimited' if self.unlimited_mode else 'circular'Circular Mode: Uses a fixed-size circular buffer (200 entries) with automatic dropping when full. Ideal for continuous monitoring with bounded memory usage.

Unlimited Mode: Allows unlimited buffer growth with timer-only flushing. Perfect for comprehensive diagnostic sessions where you need complete event history.

Disabled Mode: No buffering overhead, only critical errors logged directly. Optimal for production deployments where performance is paramount.

I unified the timer interval to 10 seconds across all modes, eliminating the arbitrary distinction between 120-second and 10-second intervals:

# Before: Inconsistent timing

flush_interval = 120.0 if enable_debug_buffer else 10.0

# After: Consistent 10-second intervals

self.buffer_flush_timer = self.create_timer(10.0, self._flush_buffered_logger)This change provides more responsive feedback while maintaining reasonable performance characteristics.

The most significant architectural improvement was moving BufferedLogger from the specific object detection node to the base MediaPipeBaseNode class:

# vision_core/base_node.py

class MediaPipeBaseNode(Node, ABC):

def __init__(self, node_name: str, feature_name: str, config: ProcessingConfig,

enable_buffered_logging: bool = True, unlimited_buffer_mode: bool = False):

super().__init__(node_name)

# Initialize buffered logging for all MediaPipe nodes

self.buffered_logger = BufferedLogger(

buffer_size=200,

logger=self.get_logger(),

unlimited_mode=unlimited_buffer_mode,

enabled=enable_buffered_logging

)This inheritance-based approach means any new vision node automatically gains sophisticated logging capabilities without code duplication.

The launch file parameters now clearly communicate their purpose:

# Before: Unclear parameter names

declare_enable_debug_buffer = DeclareLaunchArgument(

'enable_debug_buffer',

default_value=...

Read more »

In my recent work on the GestureBot vision system, I made several architectural improvements that significantly simplified the codebase while maintaining performance. Here's what I learned about building robust MediaPipe-based vision pipelines in ROS 2.

Initially, I implemented a complex architecture with ComposableNodes, thread pools, and async processing patterns. The system created a new thread for every camera frame and used intricate callback checking mechanisms. While this seemed like a performance optimization, it introduced unnecessary complexity:

# Old approach - complex threading

threading.Thread(

target=self._process_frame_async,

args=(cv_image, timestamp),

daemon=True

).start()

# Complex callback checking after submission

if self.processing_lock.acquire(blocking=False):

# Process and check callback results...I refactored the entire system to use a straightforward synchronous approach that separates concerns cleanly:

Before:

camera_container = ComposableNodeContainer(

name='object_detection_camera_container',

package='rclcpp_components',

executable='component_container',

composable_node_descriptions=[

ComposableNode(package='camera_ros', plugin='camera::CameraNode')

]

)After:

camera_node = Node(

package='camera_ros',

executable='camera_node',

name='camera_node',

namespace='camera'

)Why this works better: Since my object detection node runs in Python and can't be part of the same composable container anyway, using regular nodes eliminates complexity without sacrificing performance.

I redesigned the processing flow to have two distinct, non-blocking contexts:

def image_callback(self, msg: Image) -> None:

"""Simple synchronous image processing callback."""

cv_image = self.cv_bridge.imgmsg_to_cv2(msg, 'bgr8')

timestamp = time.time()

# Process frame synchronously - no threading complexity

results = self.process_frame(cv_image, timestamp)

if results is not None:

self.publish_results(results, timestamp)Key insight: Instead of checking MediaPipe callbacks after submission, I let MediaPipe's callback system handle result publishing directly. This eliminates the need for complex synchronization between submission and result retrieval.

MediaPipe sometimes returns None values for bounding box coordinates and confidence scores. I added comprehensive None-value handling:

# Handle None values explicitly

origin_x = getattr(bbox, 'origin_x', None)

msg.bbox_x = int(origin_x) if origin_x is not None else 0

# Robust confidence assignment with multiple fallback approaches

if score_val is not None:

confidence_val = float(score_val)

else:

confidence_val = 0.0

try:

msg.confidence = confidence_val

except:

object.__setattr__(msg, 'confidence', confidence_val)

This eliminated the persistent <function DetectedObject.confidence at 0x...> returned a result with an exception set errors that were blocking the system.

While simplifying the architecture, I maintained performance by enabling shared memory transport. This provides most of the performance benefits of ComposableNodes without the architectural complexity.

I consolidated all camera-related topics under a clean /camera/ namespace:

remappings=[

('~/image_raw', '/camera/image_raw'),

('~/camera_info', '/camera/camera_info'),

] This eliminates duplicate topics like /camera_node/image_raw and /camera/image_raw that were causing confusion.

The refactored system achieves:

Hardware Platform

I chose the Create 2 because:

In short, it gives me reliable locomotion and power infrastructure so I can focus engineering time on perception and interaction.

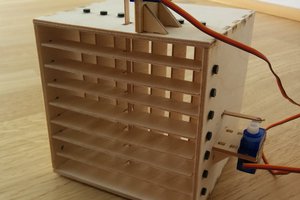

I built the superstructure as a four‑post mast using standard 3/4" Schedule 40 PVC with printed sockets at the base and a printed upper enclosure that captures the posts.

Practical tip: I lightly ream the pipe OD and size printed sockets with +0.3 to +0.5 mm clearance, then use two self‑tapping screws per joint. This holds under vibration and still allows disassembly.

The base bracket is a circular plate that sits on the Roomba’s top deck and presents four vertical sockets for the PVC posts.

Design choices:

Material and print settings:

The upper enclosure is a printed housing that integrates compute, power, and sensors while acting as the frame’s top plate. It also provides an easy surface for future sensors and user interfaces.

Create an account to leave a comment. Already have an account? Log In.

Become a member to follow this project and never miss any updates

About Us Contact Hackaday.io Give Feedback Terms of Use Privacy Policy Hackaday API Do not sell or share my personal information

Anand Uthaman

Anand Uthaman

Nick Bild

Nick Bild

hanno

hanno