AI Engineering is the application of software engineering principles and techniques to the design, development, and operation of AI Systems. It bridges the gap between cutting-edge AI models and practical, reliable system-level implementation.

This talk summarizes our recent book:

Engineering AI Systems: Architecture and DevOps Essentials. Len Bass, Qinghua Lu, Ingo Weber, and Liming Zhu. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2025.

https://research.csiro.au/ss/team/se4ai/ai-engineering/

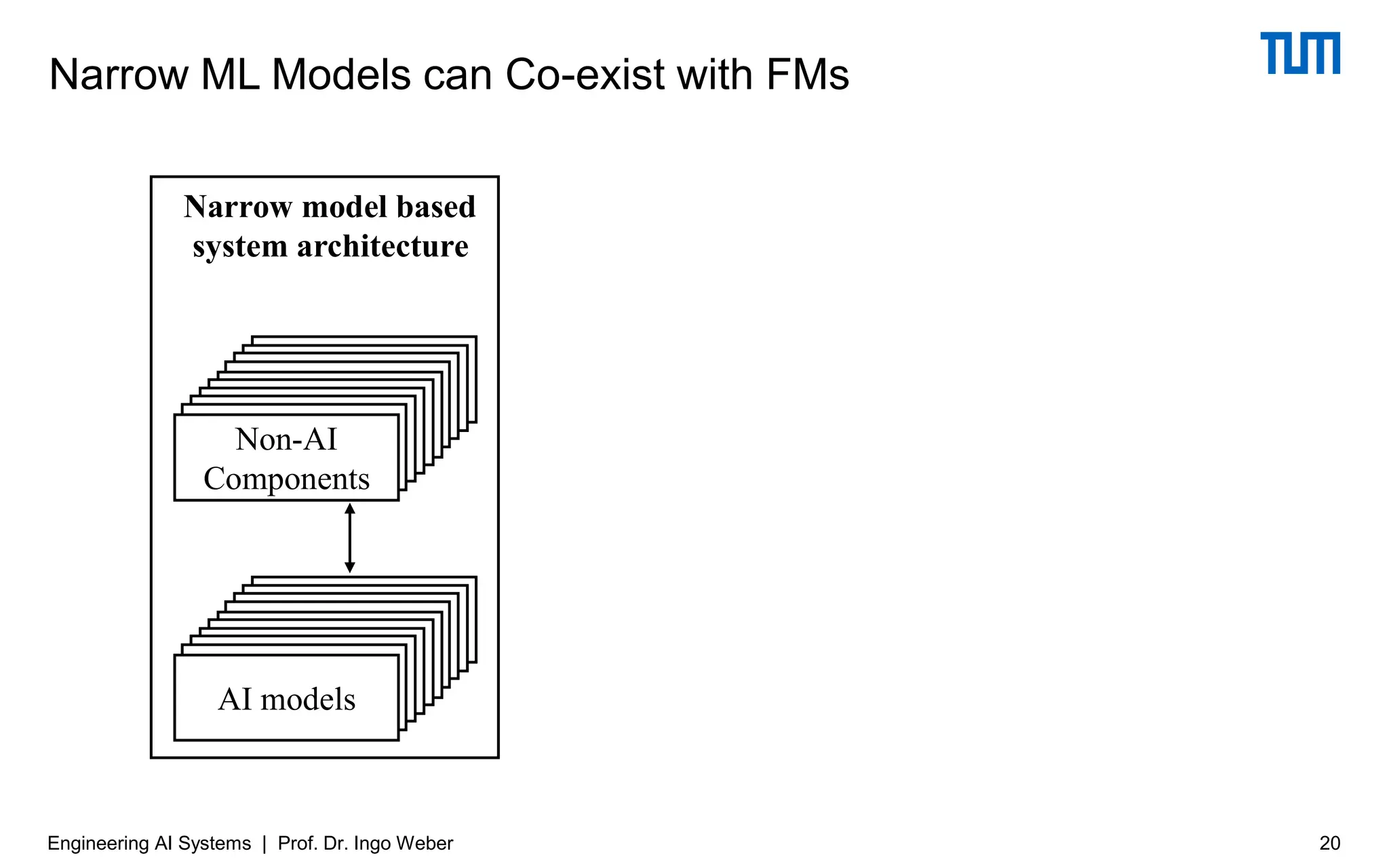

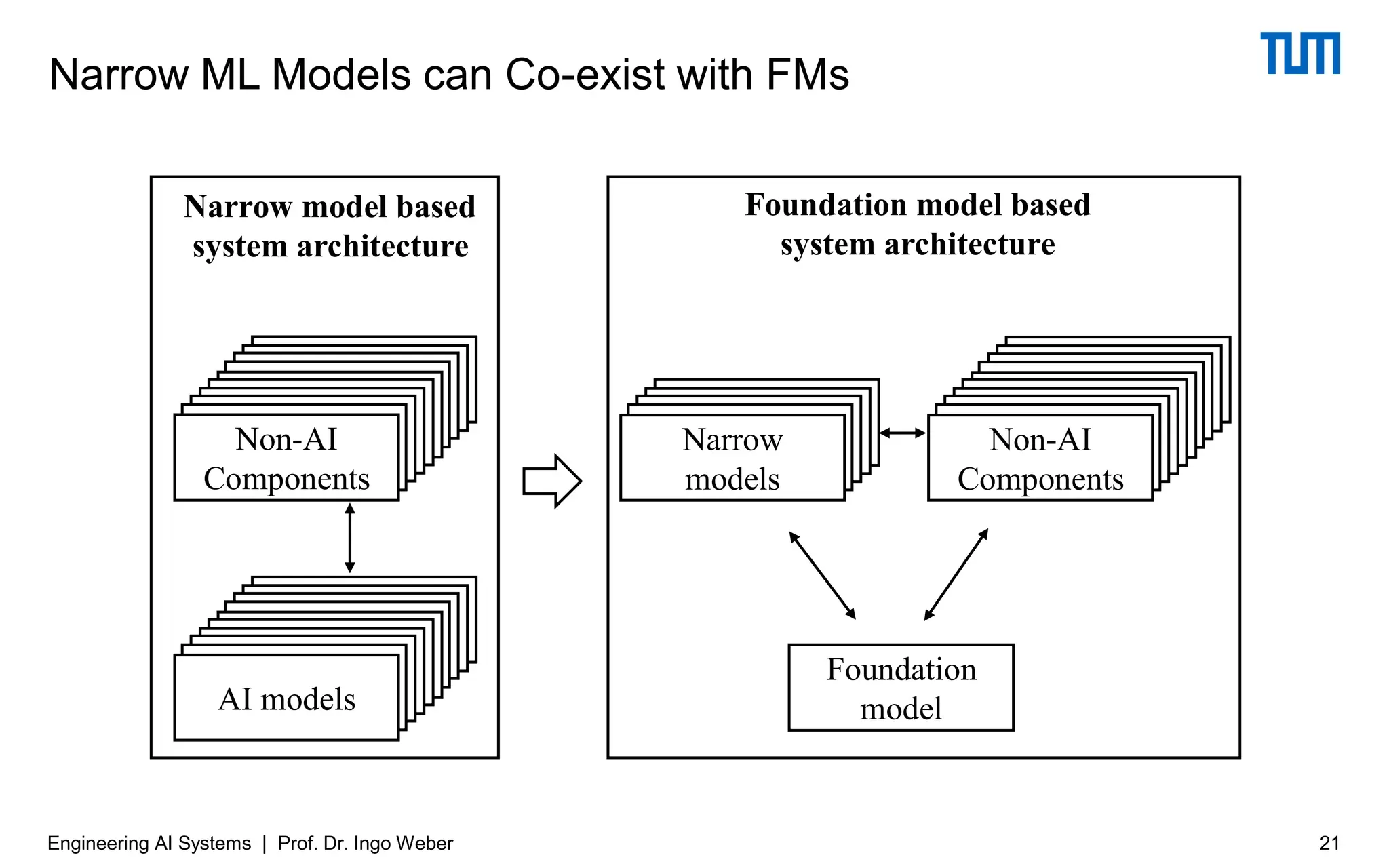

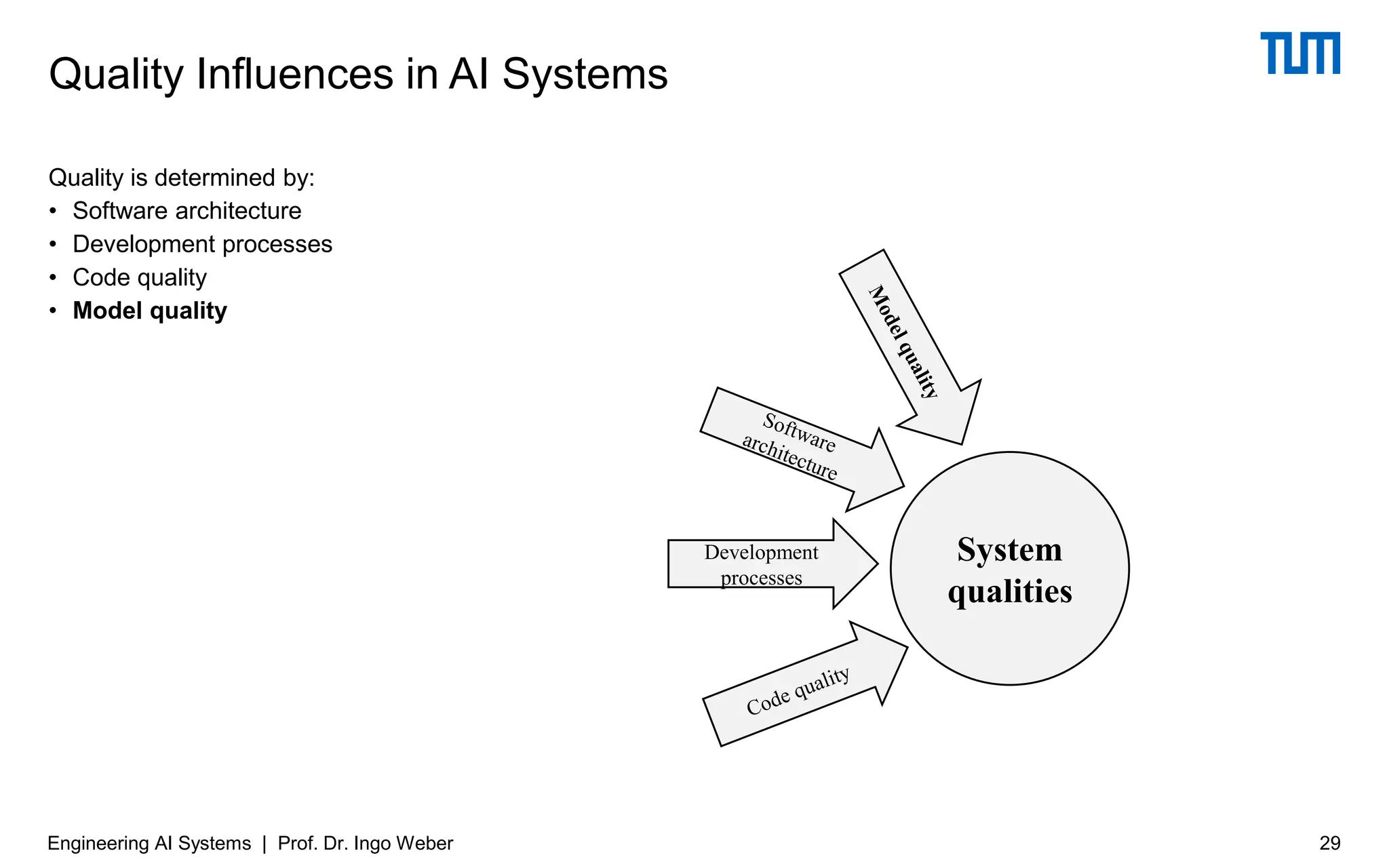

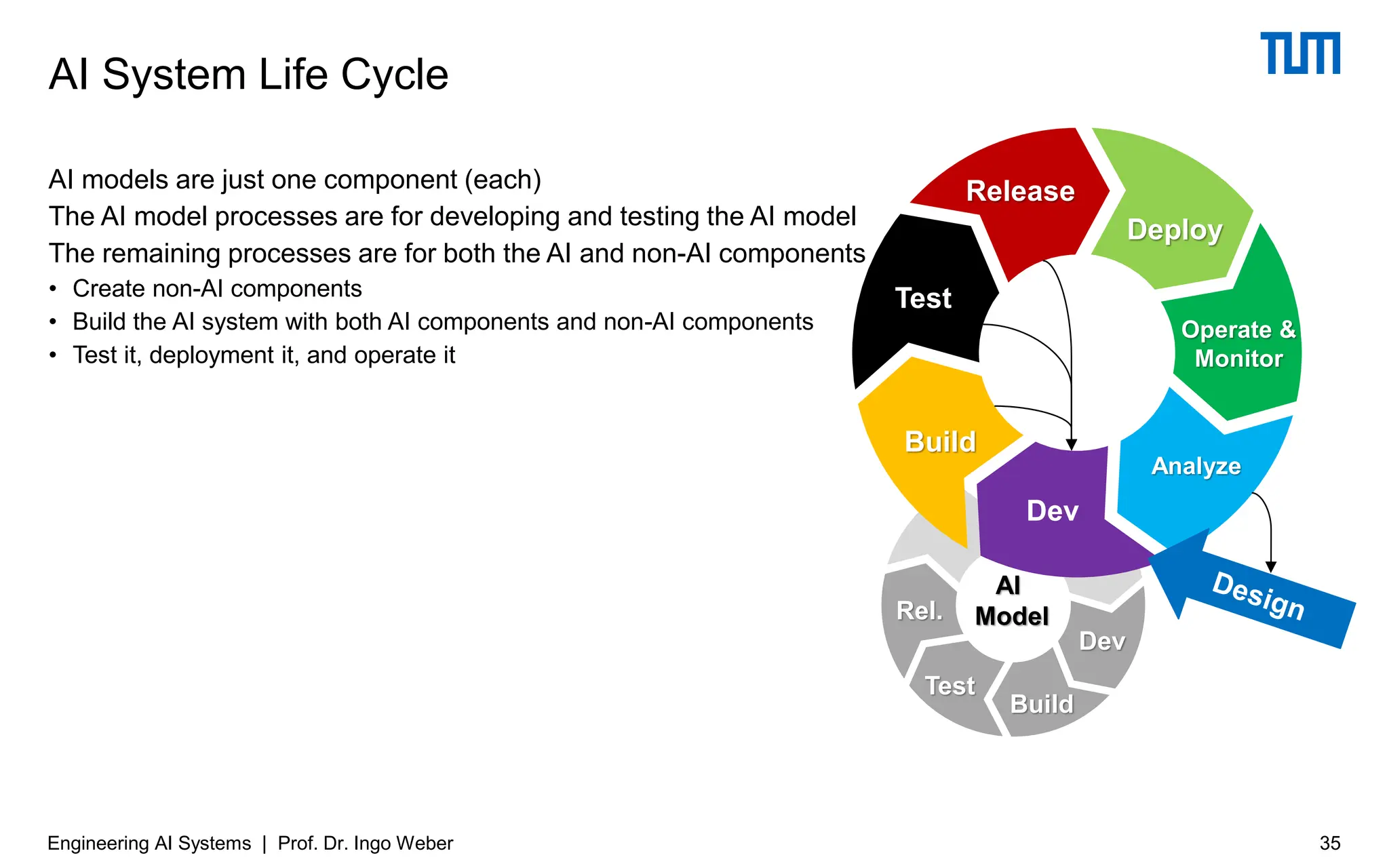

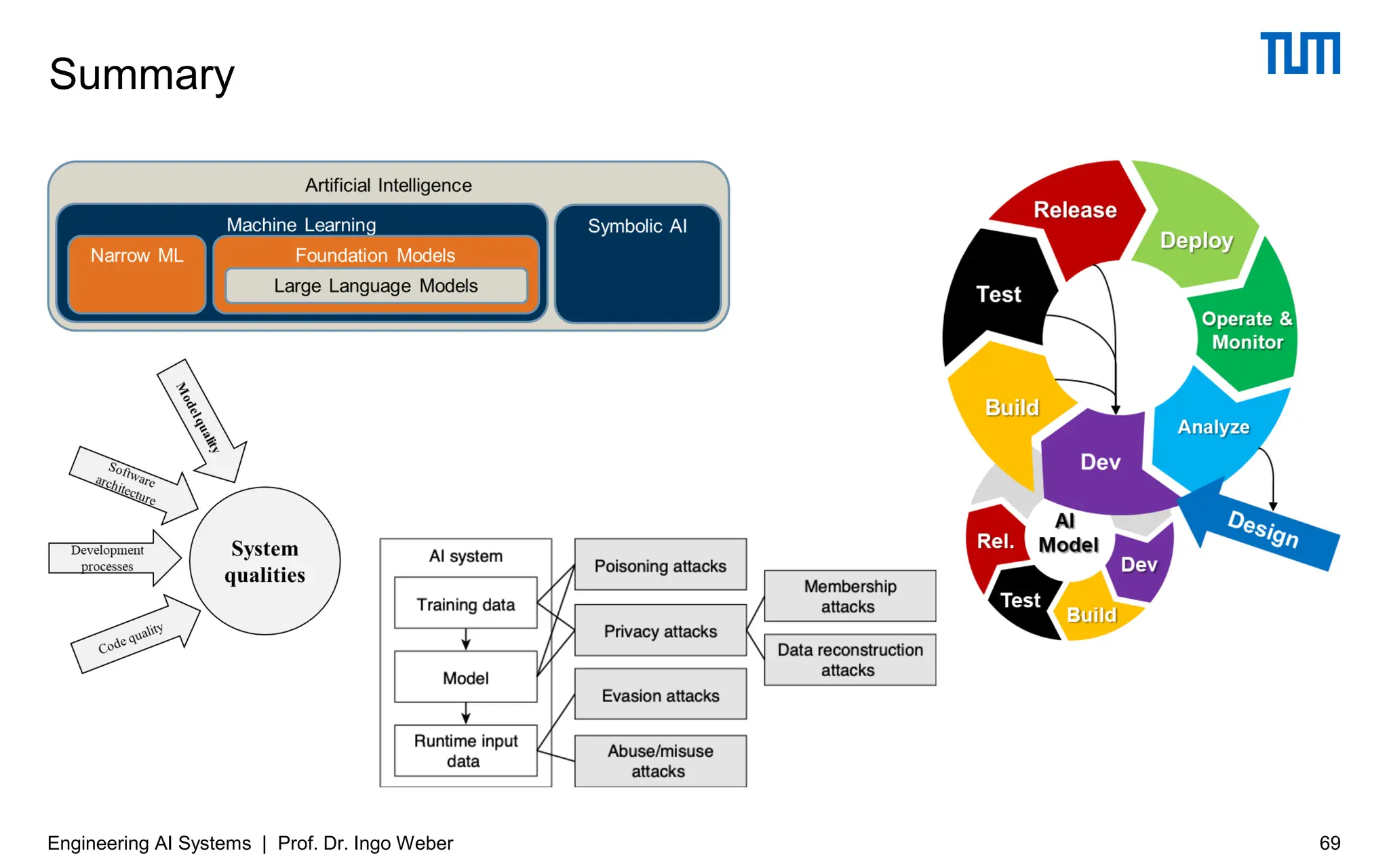

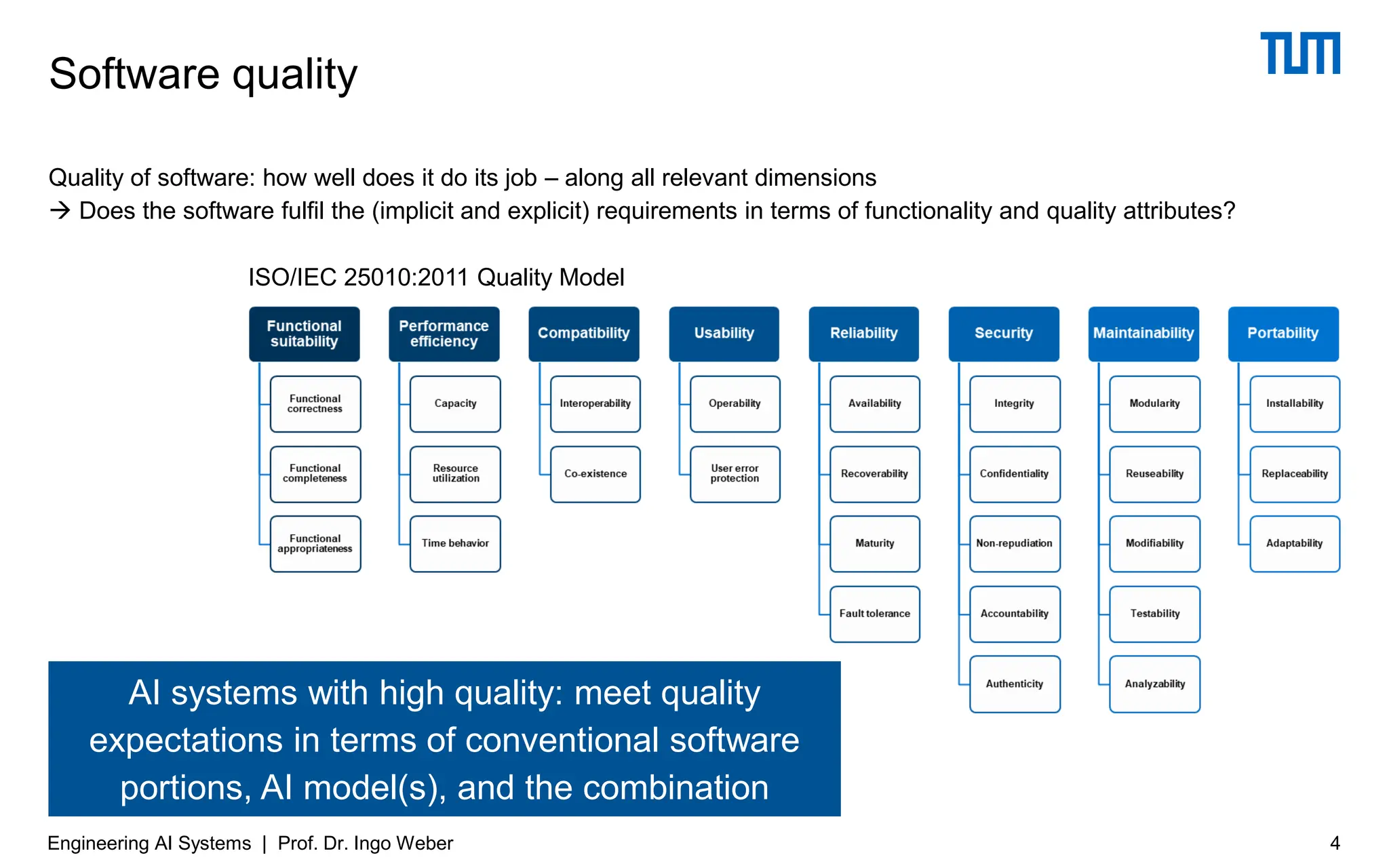

An AI system, at its core, comprises two key components: the AI portion and the non-AI portion. Most of what you will read elsewhere about AI systems focuses on the AI portion and its construction. That is important, but equally important are the non-AI portion and how the two portions are integrated. The quality of the overall system depends on the quality of both portions and their interactions. All of that, in turn, depends on a great many decisions a designer must make, only some of which have to do with the AI model chosen and how it is trained, fine-tuned, tested and deployed.

Accordingly, in this book we focus on the overall system perspective and aim to provide a holistic picture of engineering and operating AI systems – such that you, your SE & AI teams, your company, and your users get good value out of them, with effective management of risks.

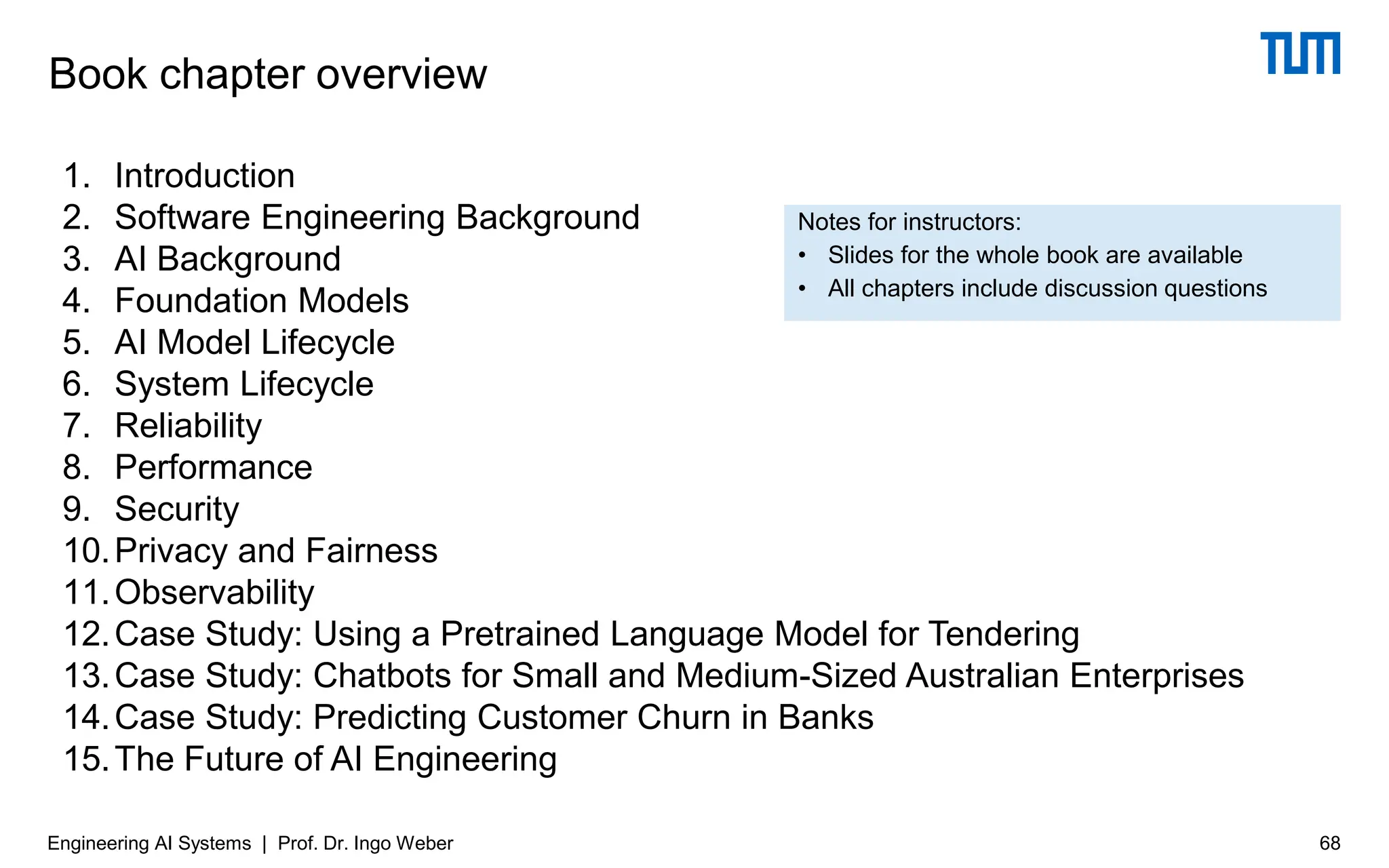

The book covers 15 chapters:

1 Introduction

2 Software Engineering Background

3 AI Background

4 Foundation Models

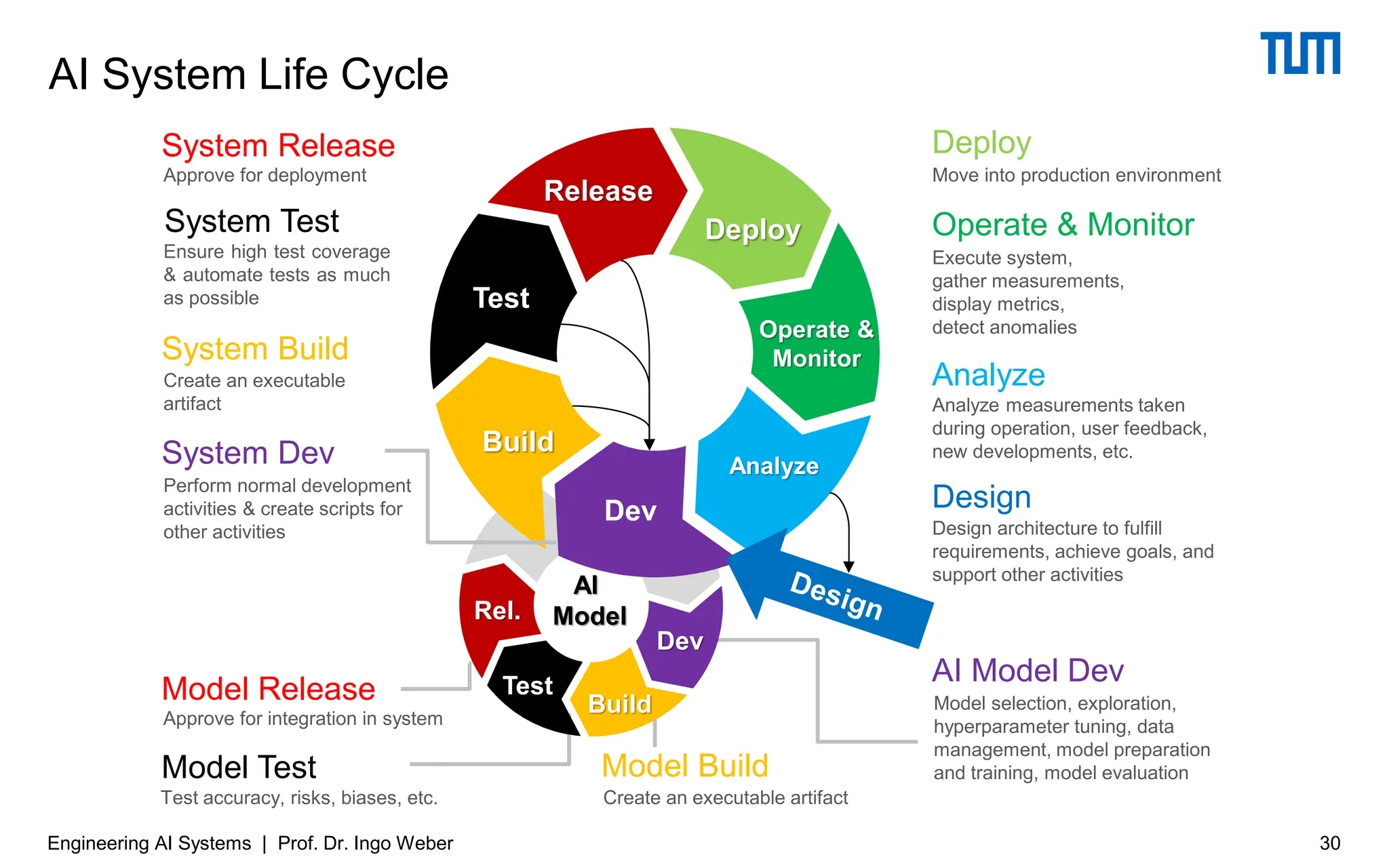

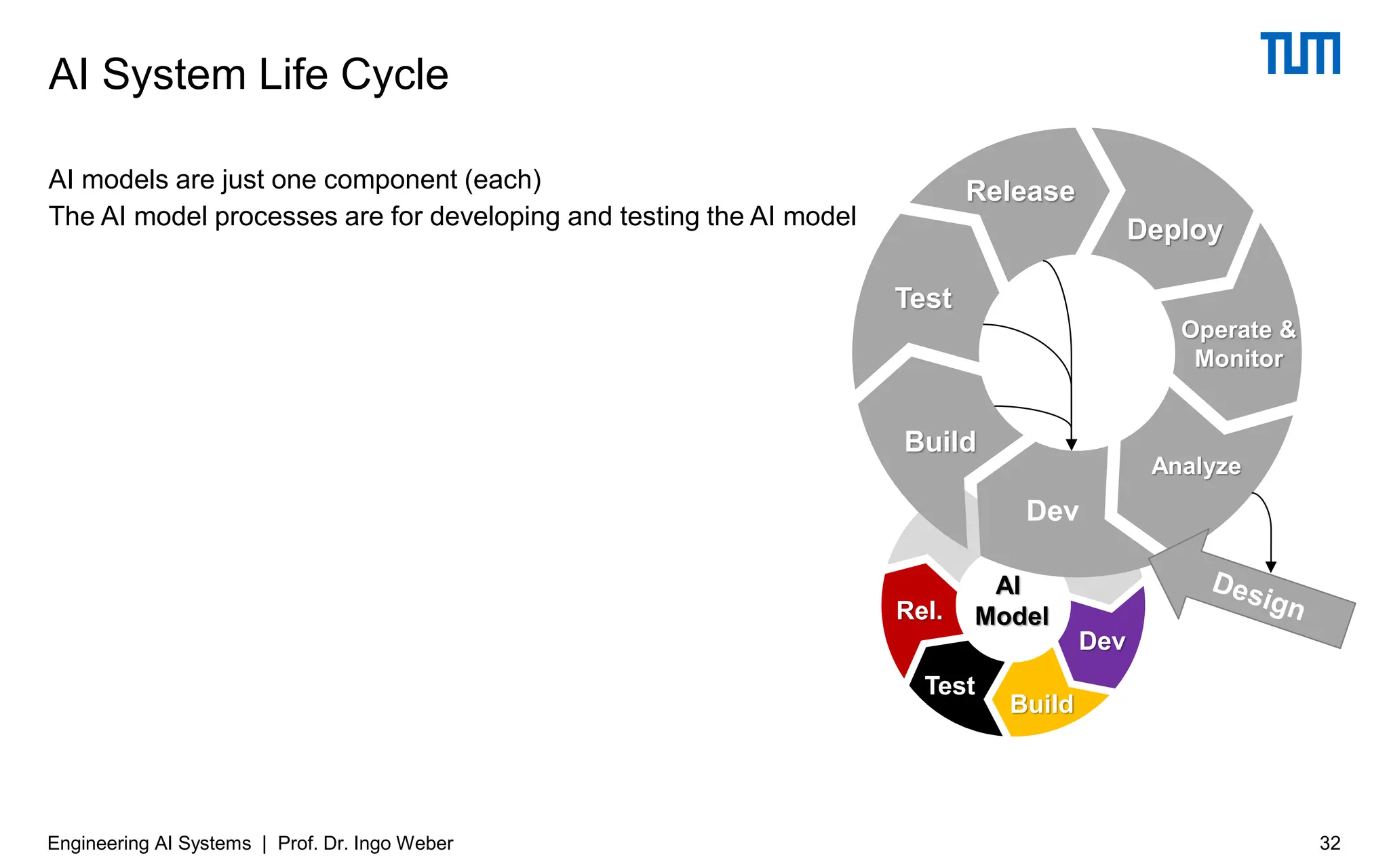

5 AI Model Lifecycle (with Boming Xia)

6 System Lifecycle (with Boming Xia)

7 Reliability

8 Performance

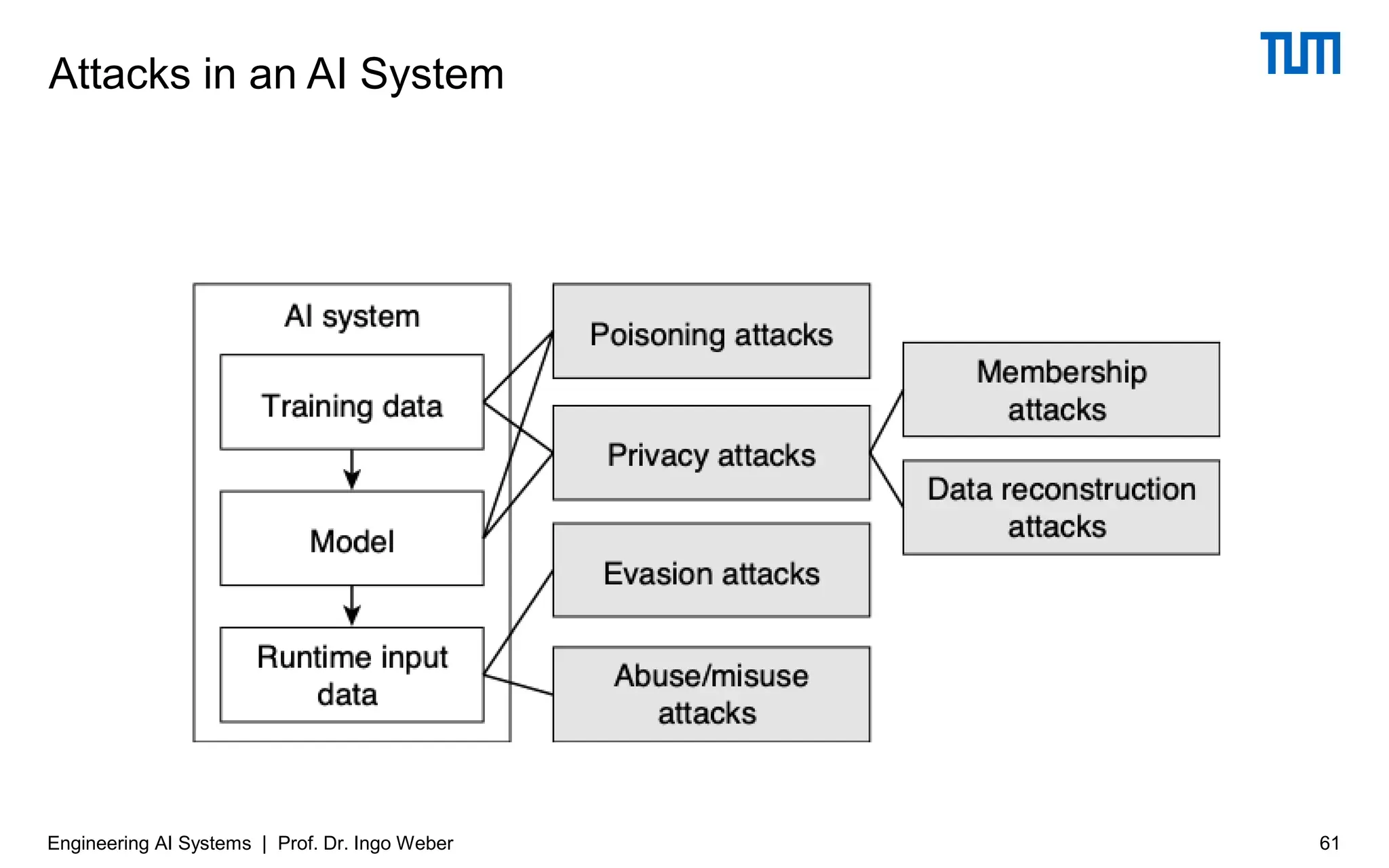

9 Security

10 Privacy and Fairness

11 Observability

12 Case Study: Using a Pretrained Language Model for Tendering

13 Case Study: Chatbots for Small and Medium-Sized Australian Enterprises

14 Case Study: Predicting Customer Churn in Banks

15 The Future of AI Engineering

The talk covers the main aspects, in particular chapters 3-6 and touches on qualities, i.e., chapters 7-11. It was delivered in November and December 2025

The slides contain content from the book, which is subject to copyright

![DevOps is a set of practices intended to reduce the time between committing a

change to a system and the change being placed into normal production, while

ensuring high quality. [DevOps book, 2015]

AI engineering is the application of software engineering principles and

techniques to the design, development, and operation of AI systems.

[AI Engineering book, 2025]

The term MLOps, analogous to DevOps, encompasses the processes and tools not

only for managing and deploying AI and ML models, but also for cleaning,

organizing, and efficiently handling data throughout the model life cycle.

[AI Engineering book, 2025]

Terminology

5

Engineering AI Systems | Prof. Dr. Ingo Weber](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/engineeringaisystems-dec2025public-251202173307-38a70d5b/75/Engineering-AI-Systems-A-Summary-of-Architecture-and-DevOps-Essentials-5-2048.jpg)