PostgreSQL stores data in fixed‑size blocks (pages), normally 8 KB. When a client updates or inserts data, PostgreSQL does not immediately write those changes to disk. Instead, it loads the affected page into shared memory (shared buffers), makes the modification there, and marks the page as dirty. A “dirty page” means the version of that page in memory is newer than the on‑disk copy.

Before returning control to the client, PostgreSQL records the change in the Write‑Ahead Log (WAL), ensuring durability even if the database crashes. However, the actual table file isn’t updated until a checkpoint or background writer flushes the dirty page to disk. Dirty pages accumulate in memory until they are flushed by one of three mechanisms:

- Background Writer (BGWriter) – a daemon process that continuously writes dirty pages to disk when the number of clean buffers gets low.

- Checkpointer – periodically flushes all dirty pages at a checkpoint (e.g., checkpoint_timeout interval or WAL exceeds max_wal_size).

- Backend processes – in emergency situations (e.g., shared buffers are full of dirty pages), regular back‑end processes will write dirty pages themselves, potentially stalling user queries.

Understanding and controlling how and when these dirty pages are flushed is key to good PostgreSQL performance.

Why Dirty Pages Matter

Dirty pages affect performance in multiple ways:

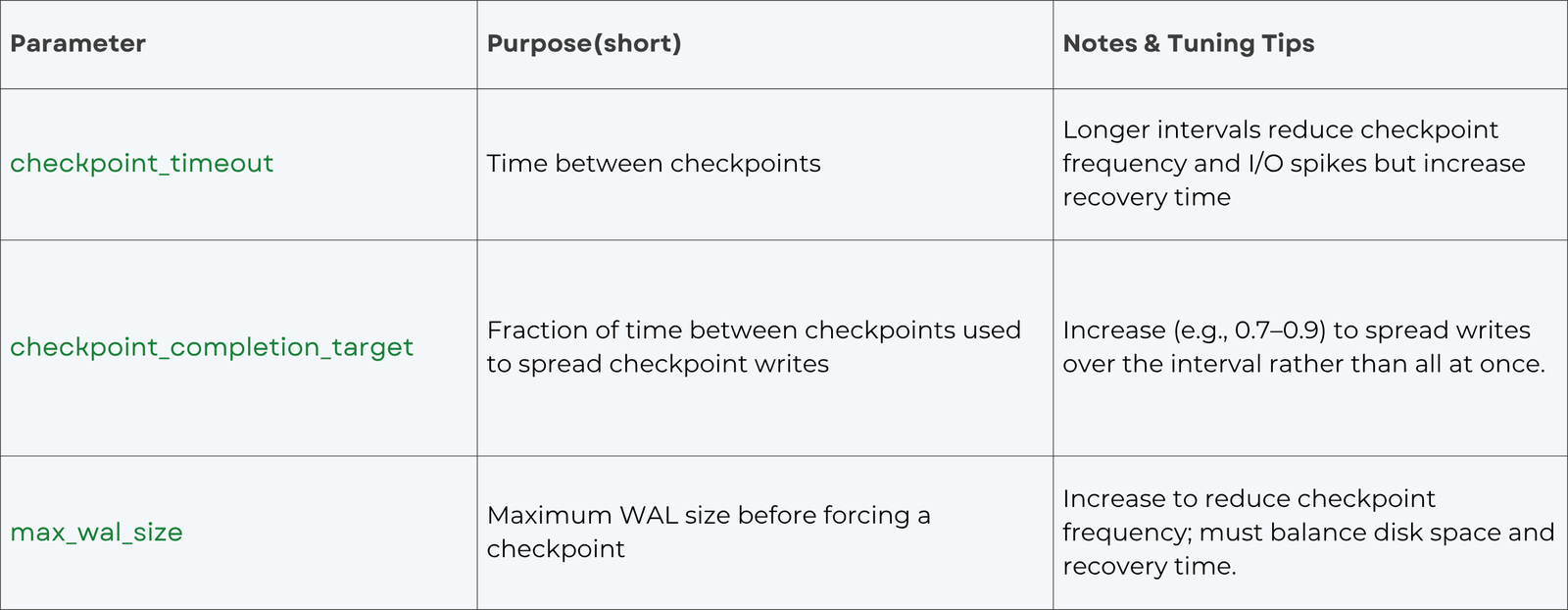

- I/O Spikes During Checkpoints: When a checkpoint occurs, every dirty page must be flushed to disk. If many pages are dirty, this flush can produce huge I/O spikes that degrade performance for other queries. The checkpoint_timeout, checkpoint_completion_target, and max_wal_size parameters control how often and how aggressively checkpoints flush dirty pages.

- Backend Writes: When the shared buffer cache fills up with dirty pages and the BGWriter can’t keep up, back‑end processes begin flushing pages themselves, stalling user queries. To minimize these stalls, adjust memory and flush parameters so that the BGWriter does most of the work. In practice, this means sizing shared_buffers generously and tuning BGWriter settings like bgwriter_delay, bgwriter_lru_maxpages, bgwriter_lru_multiplier, and bgwriter_flush_after so dirty pages are written steadily. You can also reduce checkpoint‑induced back‑end writes by increasing checkpoint_timeout, raising checkpoint_completion_target, and max_wal_size, which spreads write‑load over longer intervals and prevents sudden bursts of flush activity.

- Balance Between Throughput and Crash Recovery: Less frequent flushing (e.g., large checkpoint_timeout) reduces I/O overhead but increases the amount of WAL that must be replayed after a crash. More frequent flushing makes recovery faster but may hurt performance. Good tuning strikes a balance for your workload.

PostgreSQL Mechanisms to Manage Dirty Pages

Background Writer (BGWriter)

The BGWriter is a separate process whose job is to keep a pool of clean buffers ready by writing dirty pages in the background. According to the official documentation:

- When the number of clean shared buffers falls below a threshold, BGWriter writes some dirty buffers and marks them clean.

- BGWriter can increase overall I/O because repeatedly dirtied pages may get written multiple times in one checkpoint interval.

Key BGWriter parameters (configured in postgresql.conf) include:

Tuning strategy: Increase bgwriter_lru_maxpages and bgwriter_lru_multiplier if you notice back‑end processes are writing pages (visible in pg_stat_bgwriter). Decrease them if BGWriter causes too much I/O. Adjust bgwriter_delay to balance write frequency and CPU usage.

Checkpointer

During a checkpoint, PostgreSQL flushes all dirty pages to disk and writes a checkpoint record to the WAL. Tuning checkpoint parameters helps distribute the I/O load:

Tuning checkpoint parameters can help manage the I/O impact of dirty page flushing and reduce spikes. Increasing checkpoint_timeout and checkpoint_completion_target spreads writes over time, while max_wal_size controls when an automatic checkpoint occurs.

Shared Buffers

shared_buffers determines how much RAM PostgreSQL uses for caching data and storing dirty pages. Setting this value affects how long pages stay in memory and how often they must be flushed. We suggest 25 to 40 % of RAM for dedicated servers and note that larger values may require increasing max_wal_size to spread out writes. Overly small shared buffers lead to frequent eviction of dirty pages, causing back‑end writes; overly large values can result in huge I/O when checkpoints flush all pages at once. A balanced value and proper BGWriter tuning can minimize back‑end writes.

Autovacuum and Vacuum Freeze

Autovacuum can generate dirty pages when it updates visibility information or freezes tuples. Ensure that autovacuum runs frequently enough to prevent table bloat but not too aggressively to avoid unnecessary writes. Adjust autovacuum_vacuum_cost_limit and autovacuum_vacuum_scale_factor based on workload. On SSDs, more aggressive autovacuum can be beneficial.

How to Tune for Maximum Performance

1. Measure first: Use pg_stat_bgwriter to monitor:

- buffers_checkpoint (dirty pages written during checkpoints).

- buffers_clean (BGWriter writes).

- buffers_backend (back‑end writes).

Aim to keep buffers_backend near zero; high values mean BGWriter isn’t keeping up.

2. Size shared buffers appropriately: Start with 25 % of RAM; adjust based on workload. Use bigger shared buffers if your working set is mostly read‑heavy; reduce if write workloads cause huge checkpoint spikes.

3. Tune BGWriter parameters:

- Lower bgwriter_delay (e.g., 100 ms) to wake BGWriter more often.

- Increase bgwriter_lru_maxpages (e.g., 200–1000) and bgwriter_lru_multiplier (e.g., 3–4) to handle more dirty pages per cycle if you have a high write workload.

Set bgwriter_flush_after to a value that matches your storage system’s optimal write size. For SSDs, 512 kB–1 MB works well.

4. Adjust checkpoint behavior:

- Increase checkpoint_timeout to reduce checkpoint frequency (e.g., 15–60 min).

- Raise checkpoint_completion_target to 0.7–0.9 so checkpoints spread writes evenly.

Increase max_wal_size so checkpoints aren’t triggered too often.

5. Avoid backend writes: If buffers_backend is rising, either increase shared buffers or make BGWriter more aggressive. Back‑end writes are typically the main cause of query stalls.

6. Consider OS tuning:

- Ensure the OS’s dirty page flush settings (vm.dirty_background_ratio, vm.dirty_ratio on Linux) aren’t too high, or the kernel may hold onto dirty pages too long, causing large bursts of writeback. Keep them modest to let PostgreSQL manage its own flushing.

- Disable transparent huge pages and enable huge pages (static huge pages) for better performance if your server has a lot of RAM.

7. Regularly review performance: Each workload is different. Use monitoring tools (e.g., pg_stat_activity, pg_stat_bgwriter, pg_stat_io in PG17+) to see how your tuning affects backend writes and I/O latency. Adjust parameters iteratively.

Conclusion

“Dirty pages” are simply modified PostgreSQL pages in memory waiting to be flushed to disk. They allow PostgreSQL to batch writes and leverage the Write‑Ahead Log for crash safety. However, poorly tuned dirty page handling can lead to I/O spikes and query latency. By understanding the mechanics of shared buffers, the background writer, checkpoints, and WAL, and by carefully tuning parameters like bgwriter_delay, bgwriter_lru_maxpages, bgwriter_lru_multiplier, checkpoint_timeout, and shared_buffers, you can achieve smooth, predictable performance while ensuring data durability.