Still crazy here at TIG & MLM central, so the blog posts will be erratic at best for the time being…. Anyway, I was listening in on a student recital in the jazz division (not my class you understand—I was just an audience member), and a few things caught my ear.

complex heads, simple heads

I admired the group’s courage in tacking some pretty tricky material (a Joshua Redman piece which I wasn’t familiar with). A bit of a gamble by the performers since the head was pretty intricate, and, as I suspected, their solos didn’t quite live up to that level of complexity. It did get me wondering about some of the harmonically elaborate compositions of Coltrane and (earlier) Shorter, say, and how the melodies of those were often quite simple.

Take ‘Giant Steps’ or ‘Countdown’: were the simple ‘melodies’ (which, given their simplicity, almost seems like the wrong word for it) engineered to subdue expectations about the solo? Given the difficulty and, as

Evan Parker calls it, ‘problem solving’ nature of the changes, did Coltrane create low-key melodies so that the solo would be a shock of energy? Did he fear that writing complex melodies would make the soloist’s job, given the experimental nature of the changes, untenable?

(Later, most notably in jazz-rock and fusion, you’d start getting intricate ‘melodies’ (and considering their complexity, that also seems like the wrong word for it) over similar changes, but with the promise of solos that were of an even greater bravado of virtuosity, but that’s another story….)

(Another solution might be, admittedly from a rock sensibility, Zappa’s in which the solo only tangentially had anything to do with the ‘head’. The rhythmic and harmonic riot of ‘Approximate’ followed by a riotous guitar solo over a relatively straightforward r’n’b groove, for example. That’s, however,

definitely another story….)

jazz: year zero

Listening to the bass player walking in a pre-Carter, pre-Holland manner, the question that came to my mind was why does so much of jazz pedagogy take its year zero as 1945 (±10 years)?

Okay, we all learned jazz guitar from, say, Freddie Green onwards, but does that make sense in terms of careers—in terms of developing an individual sound—in this latter-day jazz context? We could take the model of Tal Farlow as the starting point, or Wes Montgomery. But there’s also a certain logic to taking, perhaps, John Abercrombie as a starting point. As far as I can hear (and I know I’m on very slippery ground saying this), we are living in an after-Abercrombie jazz guitar environment.

(Hey, I might be tempted to start with Nix or Sharrock, but that probably disqualifies me as a jazz guitarist ;-)

There’s an argument that goes, well, the earlier traditions—their methodologies, their practices—shaped what followed, and to understand the latter entails first learning the former (e.g. Abercrombie’s sound was informed by his models). Well, fine, however, although we could arbitrarily turn the pedagogical clock as far back as the historical record enables, we don’t do that in practice for

pragmatic reasons: life, at school and after, is too short. Neither Charlie Christian nor Django Reinhardt feature much in orthodox teaching literature, for example, for, I imagine, this reason. (Tangentially, I’m not sure that learning to ape Palestrina, as interesting in itself as it may be, is going to help a budding West European composer find their place in an after-Lachenmann sensibility.) We all learn by choosing some arbitrary (historical) starting point, and shift and skip (forwards/backwards) as the learning experience takes us.

Additionally, we (mainstream jazz audiences) don’t generally expect young(er) jazz musicians to sound like old-timers. We expect them to come from an after-Shorter, after-Jarrett, after-Carter, after-DeJohnette common practice. Very few young(er) jazz musicians are asked to perform in the ‘older-style’ unless as some kind of post-modern pantomime act, or as a house band for visiting elder luminaries (and, as that generation departs to that great club in the sky, I’ve heard less and less of these over the years). Certainly very, very,

very few of the jazz musicians I know play ’bop anymore (but maybe I just have weird friends).

Even the neo-classicists take (and now I’m on

extremely slippery ground) The Jazz Messengers (c. 1960) as their year zero.

Furthermore, a vibrant local scene gains international recognition, not through its ability to pastiche, but through its display of some distinct take on this common practice (e.g. the recent rise in visibility of many Scandinavian jazz musicians).

So why is so much of formal jazz education still stuck in the Aebersold time-line?

(BTW, I’m talking about ‘mainstream’ jazz here, sidestepping the question of how, as Bailey asks, Ayler’s music could be distilled into a ‘method’. Also, I’ve only witnessed formal jazz education at three institutions (admittedly in three different countries), so this might not be representative.)

it’s electric, dummy!

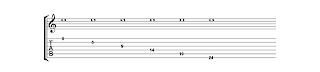

The notion that an electric guitar is just an amplified version of an acoustic has done no good whatsoever to the teaching of that instrument.

Come on, man, turn up

the amp, and pick lighter

!