One question you will see me asked a lot is 'how much money do I need to become a full time trader?'. And I usually have a handwaving answer along the lines of 'Well if you think your strategy will earn you 10% a year, then you probably want to be able to cover 5 years of expenses with no income from your trading strategy, so you need 15x your annual living expenses as an absolute minimum'. Which curiously often isn't the answer people want to hear, since objectively at that point they would already be rich and they want to trade purely to become rich (a terrible idea! people should only trade for fun with money they can afford to lose); and also because they want to start trading right now with the $1,000 they have saved up which wouldn't be enough to cover next months rent.

But behind that slightly trite question there is a more deep and meaningful one. It is a variation of this question, which I've talked about a lot on this blog and in my various books:

"Given an expected distribution of trading strategy returns, what is the appropriate standard deviation or leverage target to run your strategy at?"

And the variation we address here is:

How does the answer to the above question change if you are regularly taking a specific % withdrawal from your account?

This has obvious applications to retail traders like me (although I don't currently take a regular withdrawal from my trading account which is only a proportion of my total investments, rather I sporadically take profits). But it could also have applications to institutional investors creating some kind of structured product with a fixed coupon (do people still do that?).

There is generic python code here (no need to install any of my libraries first, except optionally to use the progressBar function) to follow along with.

A brief reminder of prior art(icles)

For new readers and those with poor memories, here's a quick run through what I mean by 'probabilistic Kelly'. If you are completely new to this and find I'm going too quickly, you might want to read some prior articles:

If you know this stuff backwards, then you can skim through very quickly just to make sure you haven't remembered it wrong.

Here goes then: The best measure of performance is the following - having the most money at the end of your horizon (which for this blogpost I will assume is 10 years, eg around 2,560 working days). We maximise this by maximising final wealth, or log(final wealth). This is known as the Kelly criterion. The amount of money you will have at the end of time is equal to your starting capital C, multiplied by the product of (1+r0)(1+r1)...(1+rT) where rt is the return in a given time period. The t'th root of all of that lot, minus one, is equal to the geometric mean. So to get the most money, we maximise the annual geometric mean of returns which is also known in noob retail trading circles as the CAGR.

If we can use any amount of leverage then for Gaussian returns the optimal standard deviation will be equal to the Sharpe Ratio (i.e. average arithmetic excess return / standard deviation). For example, if we have a strategy with a return of 15%, with risk free rate of 5%, and standard deviation of 20%; then the Sharpe ratio will be (15-5)/20 = 0.50; the optimal standard deviation is 0.50 = 50%; and the leverage required to get that will be 50%/20% = 2.5.

Note: For the rest of the post I'm going to assume Gaussian normal returns since we're interested in the relative effects of what happens when we introduce cash withdrawal, rather than the precise numbers involved. As a general rule if returns are negatively skewed, then this will reduce the optimal leverage and standard deviation target, and hence the safe cash withdrawal rate.

Enough maths: it's probably easier to look at some pictures. For the arbitrary strategy with the figures above, let's see what happens to return characteristics as we crank up leverage (x-axis; leverage 1 means no leverage and fully invested, >1 means we are applying leverage, <1 means we keep some cash in reserve):

x-axis: leverage, y-axis: various statistics

The raw mean in blue shows the raw effect of applying leverage; doubling leverage doubles the annual mean from 15% to 30%. Similarly doubling leverage doubles the standard deviation in green from 20% to 40%. However when we use leverage we have to borrow money; so the orange line showing the adjusted mean return is lower than the blue line (for leverage >1) as we have to pay interest..

The geometric mean is shown in red. This initially increases, and is highest at 2.5 times leverage - the figure calculated above, before falling. Note that the geometric mean is always less than the mean; and the gap between them gets larger the riskier the strategy gets. They will only be equal if the standard deviation is zero. Note also that using half the optimal leverage doesn't halve the geometric return; it falls to around 14.4% a year down from just over 17.5% a year with the optimal leverage. But doubling the leverage to 5.0 times results in the geometric mean falling to zero (this is a general result). Something to bear in mind then is that using less than the optimal leverage doesn't hurt much, using more hurts a lot.

Here is another plot showing the geometric mean (Left axis, blue) and final account value where initial capital C=1 (right axis, orange); just to confirm the maximum occurs at the same leverage point:

x-axis: leverage, y-axis LHS: geometric mean (blue), y-axis RHS: final account value (orange)

Remember the assumption we're making here is that we can use as much leverage as possible. That means that if we have a typical relative value (stat arb, equity long short, LTCM...) hedge fund with low standard deviation but high Sharpe ratio, then we would need a lot of leverage to hit the optimal point.

If we label our original asset A, then now consider another asset B with excess mean 10%, standard deviation 10%, and thus Sharpe Ratio of 1.0. For this second asset, assuming it is Gaussian (and assets like this are normally left skewed in reality) the optimal standard deviation will be equal to the SR, 100%; and the leverage required to get that will be 100/10 = 10x. Which is a lot. Here is what happens if we plot the geometric mean against leverage for both assets.

Optimal leverage (x axis) occurs at maximum geometric mean (y axis) which is at leverage 2.5 for A, and at leverage 10 for B (which as you would expect has a much higher geometric mean at that point).

But if we plot the geometric mean (y axis) against standard deviation (x axis) we can see the optimium risk target is 50% (A) and 100% (B) respectively:

x-axis: leverage, y-axis geometric mean

Bringing in uncertainty

Now this would be wonderful except for one small issue; we don't actually know with certainty what our distribution of futures returns will be. If we assume (heroically!) that there is no upward bias in our returns eg because they are from a backtest, and we also assume that the 'data generating process (DGP)' for our returns will not change, and that our statistical model (Gaussian) is appropriate for future returns; then we are still left with the problem that the parameters we are estimating for our returns are subject to sampling estimation error or what I called in my second book 'Smart Portfolios', the "uncertainty of the past".

There are at least three ways to calculate estimation error for something like a Sharpe Ratio, and they are:

- With a distributional assumption, using a closed form formula eg the variance of the estimate will be (1+.5SR^2)/N where N is the number of observations, if returns are Gaussian. For our 2560 daily returns and an annual SR of 0.5 that will come out to a standard deviation of estimate for the SR of 0.32; eg that would give a 95% confidence interval for annual SR (approx +/- 2 s.d.) of approximately -0.1 to 1.1

- With non parametric bootstrapping where we sample with replacement from the original time series of returns

- With parametric monte carlo where we fix some distribution, estimate the distributional parameters from the return series and resample from those distributions

Calculation: annual SR = 0.5, daily SR = 0.5/sqrt(256) = 0.03125. Variance of estimate = (1+.5*.03125^2)/2560 = 0.000391, standard deviation of estimate = 0.0197, annualised = 0.0197*sqrt(256) = 0.32

For simplicity and since I 'know' the parameters of the distribution I'm going to use the third method in this post.

(it would be equally valid to use the other methods, and I've done so in the past...)

So what we do is generate a number of new return series from the same distribution of returns as in the original strategy, and the same length (10 years). For each of these we calculate the final account value given various leverage levels. We then get a distribution of account values for different leverage levels.

The full Kelly optimal would just find the leverage level at which the average account value was maximised, i.e. the median 50% percentile point of this distribution. Instead however we're going to take some more conservative distributional point which is something less than 50%, like for example 20%. In plain english, we want the leverage level that maximises the account value that we expect to get say two out of ten times in a future 10 year period (assuming all our assumptions about the distribution are true).

Note this is a more sophisticated way of doing the crude 'half Kelly' targeting used by certain people, as I've discussed in previous blog posts. It also gives us some comfort in the case of our returns not being normally distributed, but where we've been unable to accurately estimate the likely left hand tail from the existing historic data ('peso problem').

Let's return to asset A and show the final value at different points of the monte carlo distribution, for different leverage levels:

x-axis leverage level, y-axis final value of capital, lines: different percentile points of distribution

Each line is a different point on the distribution, eg 0.5 is the median, 0.2 is the 20% percentile and so on. As we get more pessimistic (lower values of percentile), the final value curve slips down for a given level of leverage; but the optimal leverage which maximizes final value also reduces. If you are super optimistic (75% percentile) you would use 3.5x leverage; but if you were really conservative (10% percentile) you would use about 0.5x leverage (eg keep half your money in cash).

As I said in my previous post your choice of line is down to your tolerance for uncertainty. This is not quite the same as a risk tolerance, since here we are assuming that you are happy to maximise geometric mean and therefore you are happy to take as much standard deviation risk as that involves. I personally feel that the choice of uncertainty tolerance is much more intuitive to most people than choosing a standard deviation risk limit / target, or god forbid a risk tolerance penalty variable.

Introducing withdrawals

Now we are all caught up with the past, let's have a look at what happens if we withdraw money from our portfolio over time. First decision to make is what our utility function is. Do we still want to maximise final value? Or are we happy to end up with some non positive value of money at the end of time? For some of us, the answer will depend on how much we love our children :-) To keep things simple, I'm initially going to assume that we want to maximise final value, subject to that being at least equal to our starting capital. As my compounding calculations assume an initial wealth of 1.0, that means a final account value of at least 1.0.

Inititally then I'm going to look at what happens in the non probabilistic case. In the following graph, the x-axis is leverage as before, and the y-axis this time is final value. Each of the lines shows what will happen at a different withdrawal rate. 0 is no withdrawal, 0.005 is 0.5% a year, and so on up to 0.2; 20% a year.

x-axis leverage, y-axis final value. Each line is a different annual withdrawal rate

At higher withdrawal rates we make less money - duh! - but the optimal leverage remains unchanged. That makes sense. Regardless of how much money we are withdrawing, we're going to want to run at the same optimal amount of leverage.

And for all withdrawal rates of 17% or less, we end up with at least 1.0 of our final account value, so we can use the optimal leverage without any worries. For higher withdrawal rates, eg 20%, we can never safely withdraw all that amount, regardless of how much leverage we use. We'll always end up with less than our final account value even at the optimal leverage ratio.

For this Sharpe Ratio level then, to end up with at least 1.0 of our account value, it looks like our safe withdrawal rate is around 17% (In fact, I calculate it later to be more like 18%).

Safe withdrawals versus Sharpe Ratio

OK that's for a Sharpe of 0.5, but what if we have a strategy which is much better or worse? What is the relationship between a safe withdrawal rate, and the Sharpe Ratio of the underlying strategy? Let's assume that we want to end up with at least 1.0x our starting capital after 10 years, and we push our withdrawal rate up to that point.

That looks a bit exponential-esque, which kind of makes sense since we know that returns gross of funding costs scale with the square of SR: If our returns double with the same standard deviation we double our SR, then we can double our risk target, which means we can use twice as much leverage, so we end up with four times the return. It isn't exactly exponential, because we have to fund borrowing.

The above result is indifferent to the standard deviation of the underlying asset as we'd expect (I did check!), but how does it vary when we change the other key values in our calculation: the years to run the strategy over and the proportion of our starting capital we want to end up with?

x-axis amount of starting capital to end up with, y-axis withdrawal rate, lines different time periods in years

Each of these plots has the same format. The Sharpe Ratio of the underlying strategy is fixed, and is in the title. The y-axis shows the safe withdrawal rate, for a given amount of remaining starting capital on the x-axis (where 1.0 means we want to end up with all our remaining capital). Each line shows the results for a different number of years.

The first thing to notice is that if we want to maintain our starting capital, the withdrawal rate will be unchanged regardless of the number of years we are trading for. That makes sense - this is a 'steady state' where we are withdrawing exactly what we make each year. If we are happy to end up with less of our capital, then with shorter horizons we can afford to take a lot more out of our account each year. Again, this makes sense. However if we want to end up with more money than we started with, and our horizon is short, then we have to take less out to let everything compound up. In fact for a short enough time horizon we can't end up with twice our capital as there just isn't enough time to compound up (at what here is quite a poor Sharpe Ratio).

x-axis amount of starting capital to end up with, y-axis withdrawal rate, lines different time periods in years

With a higher Sharpe, the pattern is similar but the withdrawal rates that are possible are much larger.

Withdrawals probabilistically

Notice that if you really are going to consistently hit a SR of exactly 1, and you're prepared to run at full Kelly, then a very high withdrawal rate of 50% is apparently possible. But hitting a SR of exactly 1 is unlikely because of parameter uncertainty.

So let's see what happens if we introduce the idea of distributional monte carlo into withdrawals. To keep things simple, I'm going to stick my original goal of saying that we want to end up with exactly 100% of our capital remaining when we finish. That means we can solve the problem for an arbitrary number of years (I'm going to use 30, which seems reasonable for someone in the withdrawal phase of their investment career post retirement).

What I'm going to do then is generate a large number of random 30 year daily return series drawn for a return distribution appropriate for a given Sharpe Ratio, and for each of those calculate what the optimal leverage would be (which remember from earlier is invariant to withdrawal rate), and then find the maximum annual withdrawal rate that means I still have my starting capital at the end of the investment period. This will give me a distribution of withdrawal rates.

From that distribution I then take a different quantile point, depending on whether I am being optimistic or pessimistic versus the median.

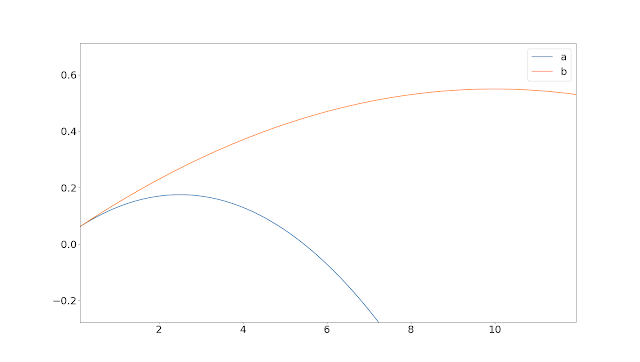

X-axis: Sharpe Ratio. Y-axis: withdrawal rate (where 0.5 is 50% a year). Line colours: different percentiles of the monte carlo withdrawal rate distribution, eg 0.5 is the median, 0.1 is the very conservative 10% percentile.

Here is the same data in a table:

PercentileSR 0.10 0.20 0.30 0.50 0.75

0.10 4.7 4.8 4.9 5.5 7.40

0.25 4.9 5.3 6.0 7.9 11.00

0.50 9.0 11.0 13.0 18.0 24.25

0.75 18.0 23.0 26.0 33.0 43.00

1.00 33.0 39.0 45.0 55.0 66.00

1.50 83.9 96.0 102.0 117.0 135.00

2.00 162.0 176.0 185.7 205.0 228.25We can see our old friend 18% in the median 0.50 percentile column, for the 0.50 SR row. As before we can withdraw more with higher Sharpe Ratios.Now though as you would expect, as we get more optimistic about the quanti, we would use a higher withdrawal rate. For example, for a SR of 1.0 the withdrawal rates vary from 33% a year at the very conservative 10% percentile, right up to 66% at the highly optimistic 75% percentile.As I've discussed before nobody should ever use more than the median 50% (penultimate column) which means you're basically indifferent to uncertainty, and I'd be vary wary of the bottom few rows with very high Sharpe Ratios, unless you're actually running an HFT shop or Jane Street in which case good luck.Footnote: All of the above numbers were calculated with a 5% risk free rate. Here are the same figures with a 0% risk free rate. They are roughly, but not exactly, the above minus 5%. This means that for low enough SR values and percentile points we can't safely withdraw anything and expect to end up with our starting capital intact.

0.10 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.4 2.8

0.25 0.0 0.6 1.4 3.6 7.5

0.50 3.6 5.9 8.1 12.0 19.0

0.75 13.0 17.0 21.0 28.0 38.0

1.00 29.0 34.0 39.0 48.0 62.0

1.50 79.0 90.0 96.0 110.0 131.0

2.00 150.9 167.0 178.0 198.5 223.0

Conclusion

I

find him strangely compelling and also very annoying. He is always

sniggering and has a permanent smug look on his face. The videos are

mostly set in exotic places where we are presumably supposed to envy

Anton's lifestyle which seems to involve spending a lot of time flying

around the world - not something I'd personally aspire to.

t

I can't comment on the quality of his education but at least he has the pedigree. He also has some interesting

opinions about non trading subjects but then so do most trading

"gurus". Mostly on trading, and on the financial industry generally,

from what I've seen he talks mostly sense.

Anyway,

one interesting thing he said is that you shouldn't use trading for

income but only to grow capital. Something I mostly agree with. Mostly

people who w

http://www.elitetrader.com/et/index.php?threads/how-much-did-you-save-up-before-you-decided-to-trade-full-time.298251/

As

a procrastination technique (I'm supposed to be writing my second book)

I've been watching the videos of Anton Kriel on youtube. For those of

you who don't know him he's an english ex goldman sachs guy who retired

at the age of 27, "starred" in the post modern turtle traders based

reality trading show "million dollar traders", and now runs something

called the institute of trading that offers very high priced training

and mentoring courses.

I

find him strangely compelling and also very annoying. He is always

sniggering and has a permanent smug look on his face. The videos are

mostly set in exotic places where we are presumably supposed to envy

Anton's lifestyle which seems to involve spending a lot of time flying

around the world - not something I'd personally aspire to.

I can't comment on the quality of his education but at least he has the pedigree. He also has some interesting

opinions about non trading subjects but then so do most trading

"gurus". Mostly on trading, and on the financial industry generally,

from what I've seen he talks mostly sense.

Anyway,

one interesting thing he said is that you shouldn't use trading for

income but only to grow capital. Something I mostly agree with. Mostly

people who w

http://www.elitetrader.com/et/index.php?threads/how-much-did-you-save-up-before-you-decided-to-trade-full-time.298251/

Since I've used a risk free rate of 5%, that implies withdrawing the risk free rate plus another 4% on top, for a total of 9%.

Note that one reason this is quite low is that in a conservative 10% quantile scenario I'd rarely be using the full Kelly (remember 0.50 SR implies a 50% risk target); this is consistent with what I actually do which is use a 25% risk target. With a 25% risk target, and SR 0.5 in theory I will make the risk free rate plus 12.5%. So I'm withdrawing around a third of my expected profits, which sounds like a good rule of thumb for someone who is relatively risk averse.

If you're more aggressive, and have good reason to expect a higher Sharpe Ratio, then you could consider a withdrawal rate up to perhaps 30%. But this should only be done by someone with a track record of achieving those kinds of returns over several years, and who is comfortable with the fact that their chances of maintaining their capital are only a coin flip.

Obviously my conservative 9% is higher than the 4% suggested by most retirement planners (which is a bit arbitrary as it doesn't seem to change when the risk free rate changes), but that is for long only portfolios where the Sharpe probably won't be even as good as 0.50; and more importantly where leverage isn't possible. Getting even to the half Kelly risk target of 25% isn't going to be possible without leverage with a portfolio that doesn't just contain small cap stocks or crypto.... it will be impossible with 60:40 for sure! But also bear in mind that my starting capital won't be worth what it's currently worth in real terms in the future, so I might want to reduce that figure further.