In the post about artists as men possessed, which inspired this series of posts, Mark K-Punk wrote about Joy Division:

"

The most disquieting section of the Joy Division documentary is the cassette recording of Curtis being hypnotised. It's disturbing, in part because you suspect that it is many ways the key to Curtis's art of performance: his capacity to evacuate his self, to "travel far and wide through many different times". You don't have to believe that he has been regressed into a past life in order to recognise that he is not there, that he has gone somewhere else: you can hear the absence in Curtis's comatoned voice, stripped of familiar emotional textures. He has gone to some ur-zone where Law is written, the Land Of The Dead. Hence another take on the old 'death of the author' riff: the real author is the one who can break the connection with his lifeworld self, become a shell and a conduit which other voices, outside forces, can temporarily occupy."

The Law of CurtisK-Punk:

"He has gone to some ur-zone where Law is written, the Land Of The Dead."

The lyrics of Shadowplay open with the image of a crossroads, which in many cultures is an Interzone, a location "between the worlds", a place where spirits can be contacted, a dangerously sacred place, "

No place to stop, no place to go".

Hecate, 'Queen of the Night', who sometimes traveled with a following of ghosts and other social outcasts, was the goddess of crossroads in ancient Greece. Oedipus met his father at the crossroads and killed him there. In Voodoo, crossroads are regarded as a favorite haunt of evil spirits and propitious to magic devices. At crossroads, the most powerful Voodoo divinity, Papa Legba, receives the homages of sorcerers and presides over their incantations and spells. Many magic formulae of Voodoo begin with the words: 'By the power, Master of the Crossroads.' The bluesman Robert Johnson reputedly sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads.

Crossroads are a locality where two directions touch and annihilate each other, a directionless place ("

...so plain to see..."), a nowhere, a no-man's land. In anthropological terms, crossroads are a liminal place, a "threshold" of or between two different existential planes, a place characterized by ambiguity, openness, and indeterminacy.

This non-place, which is a non-time as well, is where Curtis receives his stone tablets with his bitter Law.

However, Curtis does not bring back Ten Commandments from the wilderness, from his personal Mount Sinai. The Law he brings back from the Wilderness (Curtis' shamanic Otherworld), it is primarily a

descriptive law, not a presciptive law. Curtis' vision quest in the Wilderness aim to describe, understand and predict the cruelties of social life: travelling "

...far and wide to many different times...", Curtis brings back visions which underline his proposition that social life invariably, unchangingly is cruel. In Wilderness, the laws of Curtis are statical (not dynamical) laws of social existence.

In Wilderness, prescriptive law plays only an indirect role, showing through in his feelings of indignation, guilt, and shame at seeing moral laws transgressed. Nevertheless, the fact that these feelings show through so strongly indicate that the relation between the two types of law is highly relevant in understanding Curtis' situation. For Curtis descriptive law (the cruel laws governing social life) and prescriptive law are fundamentally incongruous, conflicting: the laws of social life ordain that the laws of morality will always be trampled underfoot.

In fact, I am reminded somewhat of the Marquis De Sade's 1787 novel '

Justine (or The Misfortunes of Virtue)'. In this novel too the descriptive and prescriptive laws are at odds. Justine's morals, the virtuous protagonist's prescriptive laws are confronted with the descriptive (metaphysical) law which makes those who live a life of evil and vice prosper, whilst the morally pure suffer. A Sadean reading of Joy Division - perverse pleasure at Curtis' dejection - is entirely possible, though in all probability quite rare.

Curtis takes an intermediate position between Marquis De Sade and Justine. Justine, though confronted with wickedness, perversions and crimes at every turn, blindly clings to her moral laws, remaining unaware of the evil character of Nature. Marquis De Sade on the other hand is conscious of the monstrosity of Nature, and this consciousness leads him to embrace all evil. Curtis, unlike Justine and like De Sade, is painfully aware of the corrupt nature of social life; but like Justine and unlike De Sade, he does not reject prescriptive law.

What strikes me about the lyrics of Wilderness is that they employ imagery of a Christian nature - surprising for a band which has a nihilist reputation. The lyrics mention saints, the Cross, sin, the blood of Christ, and martyrs. In this context, the 'one-sided trials' seem to refer to Pontius Pilate's trial of Jesus and subsequent trials of Christian martyrs.

In fact, there is something Christian about Joy Division's lyrics, which insistently extol suffering, which present us with a "mortification of the mind". Furthermore, Pilate's executioners may have nailed Christ to the Cross, but the crucifixion was a sacrifice of God. In the sacrifice of Christ the position of the victim is sanctified, while the position of the sacrificer is disavowed. If I examine Curtis' lyrics with the scheme of sacrifice in my mind, Curtis presents himself primarily as the victim, not as the sacrificer. The sacrificers are generally external agents: the leaders of men, the architects of law, the conquistadors who took their share, the figures from the past, the people who pay to see inside asylums with doors open wide, the 'you' in whom 'I put my trust', the 'you' who 'treats me like this'. Like Christian thought, Curtis disavows the sacrifiers.

However, unlike Christian suffering, Curtis' suffering brings him no interior peace, no spiritual joy, no salvation. Curtis is like Benjamin's

Angel of History, who also looks backwards and not towards a future redemption: '

His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe that keeps piling ruin upon ruin and hurls it in front of his feet.' 'No future' means 'No Redemption', means 'No Kingdom Come'; teleology and salvation have slipped from our grasp.

Furthermore, in some lyrics the conflict of prescriptive and descriptive law rages even within Curtis himself. In these lyrics, Curtis no longer disavows the sacrificer, but experiences himself as guilty. Humanity's guilt of killing Jesus Christ assumes an unlimited nature. The leaders of men, the conquistadors who took their share, and all the others are no longer the only actors in the drama of sacrifice, since the fault devolves on all humans. In the end, even Curtis, even Christ himself, is tainted. In these lyrics, Curtis' torment takes on a tragic dimension.

Mother, I tried, please believe me

I'm doing the best that I can

I'm ashamed of the things

I've been put through

I'm ashamed of the person I am

Isolation (3)

But if you could just see the beauty

These things I could never describe

Pleasures and wayward distraction

Is this my wonderful prize?

Isolation (5)

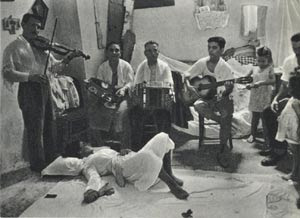

Ernesto De Martino's fascinating 1961 ethnography of Apulian Tarantism, 'The Land of Remorse: A Study of Southern Italian Tarantism' is strongly influenced by the idealist humanism of Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce.

Ernesto De Martino's fascinating 1961 ethnography of Apulian Tarantism, 'The Land of Remorse: A Study of Southern Italian Tarantism' is strongly influenced by the idealist humanism of Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce.

.jpg)