I guess that’s not just me. Benjamin B. Barber begins his essay, which begins the 1990 compilation The Legacy: The Vietnam War in the American Imagination (Beacon Press): “There is no event in America’s recent history more painful—more memorable yet less remembered—than our long and futile military engagement in Southeast Asia...Vietnam is an invitation only to amnesia—a hard and numb scar we prefer not to notice.”

On a track of Randy Newman’s great 1970 album 12 Songs, the singer describes the promising start of a love affair, except that she wants to talk about the war. “I don’t want to talk about the war” the singer asserts.

By the time I heard this song I was heartily sick of talking about the war. I had been talking about it, thinking about, bewildered and angry, bitter and immensely sad about it, for what seemed like forever, even if, all told, it took up a wearisome decade. In particular I was aware of how it was poisoning my college life and beyond, my early to mid 20s, with all of its immutable experiences and all of its urgency in determining the course of my life.

For we were shadowed by Vietnam war events until, for a few years we ate, drank, slept, read and talked the Vietnam war, and what it was doing to our personal lives, our generation, our country and humanity, as well as the people living and dying in that faraway land.

Meanwhile it took friends and acquaintances and distant contemporaries, wounding their bodies, minds and lives, and killing them dead, whether they fought in the war, fought against it, or otherwise witnessed it close up. It deformed the country, turning family members, friends and generations against each other.

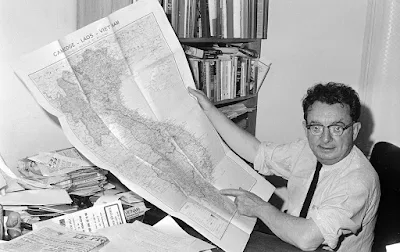

|

| Knox History prof John Stipp |

Our professors placed the American military presence in the context of the geography and history of southeast Asia and Vietnam specifically, from even before the French Indochina war. They described political and moral implications. They provided facts and sources that already contradicted US official statements.

Their scholarship and analyses (some familiar, some not) were daring to contradict official policy, lambasting the mistaken reasons for a war and its conduct while it was happening. This was academic discourse with a contemporary purpose. It meant something to our lives at that moment. And it was at least a little dangerous for them, as it would be very dangerous particularly for the male students listening, and not listening.

That spring of 1965 was when the US became fully involved in a war in Vietnam, with the first ground troops, the first search-and-destroy missions and in particular, the first bombing of North Vietnam. Escalation (a word we were learning) continued through the summer, and so student interest also escalated the following fall. I’m hazy on whether it was my first or second year that I took a public position against the war in a debate sponsored by the Speech department, but I remember it as a defining moment for me.

Then by 1966 and 1967, Vietnam was on everybody’s mind. We saw our time, thought and emotions absorbed by meetings, debates, petitions, marches, demonstrations with four or five people or thousands—in hot rooms, in the cold and snow, in the rain, and a broken-hearted poetry reading in the spring sun. Draft calls began to ramp up, which added to the urgency for those of us facing the draft in our near future.

Much of the reading I remember was in pamphlets, booklets and periodicals. We relied on periodicals partly because these events were happening rapidly, and books take a long time. But a lot of the press seemed to be simply repeating government and think tank misinformation and lies. We relied on different periodicals, such as Ramparts and the New York Review of Books, which published, among others, Mary McCarthy’s journalism (collected in Vietnam, 1967) and Noam Chomsky’s analyses.

In The Nation magazine I was particularly reading William Eastlake’s columns from Vietnam, probably before and certainly after he taught a semester at Knox. Esquire under editor Harold Hayes published provocative pieces, as did Harper’s Magazine. I didn’t regularly see the better New York Times reporting while I was at Knox, mostly because the paper didn’t get to the Knox Library for several days by mail. I might read the Sunday Times on Wednesday, if I remembered.

|

| I.F. Stone |

There are now several collections of I.F. Stone’s work. The two I have are The I.F. Stone’s Weekly Reader (1974) and Polemics and Prophecies 1967-1970 (1972.) Also in the early 70s, when the poet Celia Gilbert, my colleague and friend at the Boston Phoenix, turned out to be I.F. Stone’s daughter, I got the opportunity to meet him several times.

“It is time to stand back and look where we are going,” Stone wrote in early 1968. “And to take a good look at ourselves.” The students I knew felt this was something we were more or less forced to do just about every day.

Eventually the periodical reporting got into book form. I read Jonathan Schell’s long article in the New Yorker in the summer of 1967 that became the book, The Village of Ben Suc, a detailed account of the destruction of a Vietnamese village by American troops.

But the book that had the most direct and profound effect on me in my college years was an unheralded paperback by an unknown author. It was Air War: Vietnam by Frank Harvey, a factual account of exactly what the title said. I read about it in Robert Crichton’s review in the New York Review of Books, and the excerpts he quoted were so horrifying that, when I read them aloud as part of Bill Thompson’s teach-in in the Gizmo, I had to choke back the tears.

The Bantam paperback was troubling and exhausting, mundane and horrifying—I often had to stop reading, fearful I would fall into a melancholy without end. The incredible damage that this bombing did was almost beyond understanding—I still remember one fact: B-52 bombers—with conventional bombs-- could kill every living thing within a fifty mile radius.

This book led me many years later to Gerald J. DeGroot’s 2005 The Bomb: A Life (about the atomic bomb) and in particular Sven Lindqvist’s A History of Bombing (The New Press, 2002.) I wrote about the latter book in a piece for the San Francisco Chronicle, on the eve of the bombing of Baghdad that began the Iraq war. Lindqvist’s book further deepened my conviction that arose from Frank Harvey’s book in 1967, that all bombing of civilian settlements is fundamentally immoral.

When the internal government documents purloined by Daniel Ellsberg—which later became known as the Pentagon Papers-- began appearing in 1971, they confirmed what some of us already knew or at least strongly suspected. The pattern of official lies was there for all to see. In his 1972 book Papers on the War, Ellsberg used them as a basis for his recollections about Pentagon analysis and how it was used, and misused.

Two of the classic nonfiction books on the Vietnam war appeared near its end. Fire on the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam was a nearly 600 page history by scholar and freelance journalist Frances FitzGerald, published in 1972. Some of it had appeared in The New Yorker. It won a Pulitzer.

A year later, former New York Times reporter David Halberstam devoted more than 800 pages to a history of hubris-directed policy on Vietnam in The Best and The Brightest. By then I was the books editor at the Boston Phoenix, and interviewed Halberstam on this book (his first) in the Boston Ritz hotel—his energetic eloquence and intimate buzzsaw voice that made him a talk show favorite for decades were already in evidence.

I also met Frances FitzGerald, when we were both at a futurist convention in Washington on assignment to different magazines, and again in New York. She also had abundant wit and charm, but she was not as much of a media personality as Halberstam throughout a writing career that also resulted in a number of distinguished books on a variety of subjects.

The memoirs and fiction from the Vietnam war mostly came later, towards the end of the war or afterwards, such as Ron Kovic’s Born on the Fourth of July (which exposed the horrors of the medical care wounded veterans received, years before this became a public issue), Michael Herr’s Dispatches (expanding on his work as a Vietnam correspondent for Esquire) and Tim O’Brien’s Vietnam books. In the 1992 book Vietnam, We’ve All Been There: Interviews with American Writers, Herr and O’Brien both had trouble describing the nature of their books—memoir, New Journalism or fiction? It seems these war experiences required hybrid forms.

But in the late 1960s, three of the contemporary novels we were reading that had some bearing on Vietnam were actually about World War II. All three employed black humor to expose the deadly folly. Castle Keep by William Eastlake was about the war in France and later Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughter-House 5 was about the firebombing of Dresden. But the novel everyone I knew was reading in my later college years was Joseph Heller’s Catch-22.

Here was a war novel unlike any other, especially for young men like me who had grown up on war movies and war comics and playing at war with our friends using World War II surplus and souvenirs.

The main protagonist is an American bomber pilot named Yossarian, who is convinced that the American military is trying to kill him. The novel is a model of the painful humor of the absurd. But that insight wasn’t absurd to me. By its actions, I was convinced that my country was trying to kill me, or at least cynically devaluing my life by using me as an instrument for unjustified ends. And though one could argue whether this was chiefly impersonal or semi-personal, even today I can’t see much evidence that I was wrong.

It was a point of view buttressed by a few other things we were reading and hearing about in the late 60s. One was The Report From Iron Mountain, about a supposed secret government commission that concluded that war was necessary to the US economy and way of life, including the need for combat deaths. Eventually it was claimed to be a satire, that no such commission existed, but its arguments remained.

The other was a Selective Service memo on “channeling”: the use of the draft and draft deferments to channel young men into desired occupations useful to the military, or—in the parlance of the time—to the military-industrial-university complex. (This language in Selective Service documentation for years has since been confirmed.)

This spoke to the larger context as well as to a specific subject of great moment: namely the draft and what to do about being drafted.

I remember talking with draft counselors in Chicago several times. Some were sponsored by American Friends and other pacifist organizations with religious affiliations. Others were more specifically against the Vietnam War, and offered technical knowledge and advice on laws governing the draft, including our rights as potential and actual draftees.

So I read a lot of associated pamphlets and booklets and books, a few of which survive in my collection, if not specifically in my recollections. One is We Won’t Go: Personal accounts of war objectors, collected by Alice Lynd in 1968 and published, as many of these books were, by Beacon Press. Another is In Place of War: An Inquiry into Nonviolent National Defense, prepared by a working group of the American Friends Service Committee, and published in 1967 by Grossman. It's a thought-provoking thought experiment in a different kind of civil defense.

|

| 1967 poetry reading at Knox College. Leonard Borden photo. |

Bly’s collection, published by his own Sixties Press, contained some nonfiction excerpts by I.F. Stone and others, appropriate lines from Walt Whitman and Abraham Lincoln, and poems by contemporary poets who participated in group readings. They included Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Robert Lowell, George Hitchcock, James Wright, Donald Hall, John Logan, Louis Simpson, William Stafford, Robert Creeley and Bly.

Denise Levertov visited in the spring of my senior year, and handed out antiwar factsheets as well as her antiwar poems. I was one of the students granted a few private minutes with her, up in Sam Moon’s office. I remember I brought her a cup of tea from the Gizmo, which pleased her. I recall mentioning to her how the barrage of news and necessary decisions relating to the war was becoming overwhelming to “us.” Some wondered, I said, if we could even justify doing anything else. She was startled by this, and quickly affirmed that of course we should still take time to do life-giving things every day, like read, write and “think about your dreams.” It was that think about your dreams everyday that stuck with me.

(Levertov also edited the 1968 Peace Calendar and Appointment Book for the War Resisters League, which interspersed poems among the calendar pages by scores of American poets, including William Stafford, Robert Duncan, Jonathan Williams, Nancy Willard, Galway Kinnell, Sam Hazo, Gilbert Sorrentino and Jim Harrison, as well as these poets who visited Knox while I was there: Robert Creeley, Robert Bly, Gary Snyder, David Ignatow, Mitchell Goodman and Levertov.)

I left Knox in 1968 without a degree, vulnerable to the draft. I kept changing my official address all summer—a tactic recommended by one of those draft counseling handouts or articles—so a draft notice couldn’t find me. In the fall I became a student in fiction and poetry writing at the Iowa Writers Workshop, but I never really settled in Iowa City. I was often in restless transit, to Galesburg, to Chicago where Joni was living in the Del Prado Hotel near the lake on the South Side along with other student teachers for a semester in the Chicago school system. And back again to my narrow winter room, my pork tenderloin sandwich at the lunch counter before class on Tuesday afternoons, with the Moody Blues on the jukebox.

But my every step seemed dogged by the draft. I was sunk into myself and my conundrum. I learned one thing from responses in every place, from family, lovers, friends and other strangers. That no one knew what I felt as I faced what was before me. Only other young men with a draft physical looming at that moment could begin to fathom it.

|

| From Alice's Restaurant (1969) |

I was called for a pre-induction physical in Chicago. I caught the train from Galesburg, and had my draft physical straight out of a nightmare Alice’s Restaurant movie. I had hearing test results with me that clearly showed I was functionally deaf in one ear, which I’d been assured by a joyful draft counselor would get me out. But it didn’t.

Among the multiple ironies--none of which I was in the mood to savor at the time--was that my fondest ambition at age 11 or 12 was to become a Naval Academy midshipman. Because Members of Congress could appoint a qualified candidate to Annapolis, I figured I had a chance, since I was known to ours. But I think I can remember the moment--trotting down the steps made of piled rocks from my house to the street-- when it came to me: I could not meet the Annapolis physical standards because of my deafness, and there was nothing I could do about it. And so I had to give up that dream. All that I knew about Army standards now told me my deafness should be disqualifying again.

But standards seemed to be functionally relative. There were quotas to meet, and it was a high draft call that month. Still, the times were such in the late 60s, and the war so controversial, that substantial disagreement if not dissidence had begun to appear within the military. This was clear at the draft physical. Comparing notes later with others from Knox and Galesburg who had their physical that day, it seemed that its outcome depended more on the luck of the draw than any factual basis. If your line led to a sympathetic doctor, and you wanted out (some even asked), he got you out. If it led to a functionary or an angry true believer, you were in, no matter what. I was unlucky.

There was a written part to the exam. We started out at school desks in rooms set up like school rooms, filling out forms and taking psychological tests, directed by a no-nonsense young lieutenant.

After our humiliating physicals we returned to the same room for further forms. When we finished, the lieutenant closed both doors, and told us what it was really like in Vietnam. It was the most powerful anti-war message I had yet received. He told us that in effect our lives were being thrown away.

Dazed and disoriented, I managed to also get my wallet stolen so I left penniless as well as hopeless. I borrowed a dime for a pay phone to call Joni at the Del Prado.

But I soon went back to the pamphlets and books, wrote letters and got an appeal physical. Unfortunately it was also going to be my induction physical. If I passed, I would be inducted into the army.

I also started the process of obtaining conscientious objector status. I’d been corresponding with William Eastlake, and he cautioned me not to let my perfectly reasonable objections to the Vietnam war become opposition to all wars—a justifiable one might come along any day, he wrote.

At the time, CO status was granted almost always only on religious grounds if you were a member of a recognized church, and only if you were conscientiously opposed to all wars and killing, and not only to killing in this war.

But this was the only war they were going to send me to fight or support. And potentially killing me wasn’t as infuriating as forcing me to kill others I had no reason to harm. The first might kill my body, but the second would definitely kill my soul. To me this was personally and morally clear. It was defining.

Still, I was torn about CO status, but I filled out the forms, and I was prepared to use them if necessary.

And if all else failed, I knew my last step. There would come a moment in which inductees would be asked to take one step forward, indicating they accepted induction. That was a step I would not take. That would set off another process which could send me to prison, if I didn’t figure out how to survive in Canada first.

My appeal/induction physical was at Fort Des Moines in Iowa. The Obamas stayed at the Fort Des Moines Hotel, but it’s a little different from the place where I stayed back then, in the barracks for three nights. My physical lasted three days.

I got to Des Moines early, and spent a giddy afternoon with a girl I met, whose name was Trish. She worked at the phone company. We walked around in the sunny air and may have gone to a movie. I do remember that we eventually were talking to each other in slight English accents. It was a time when the practice of youth, freedom, sunshine and innocence was summarized by the Beatles.

I arrived on time at Fort Des Moines, though my actual physical was to be the next day. I was billeted in a barracks for the night with at least a hundred others from all over Iowa, most of them younger and very excited and eager to be leaving Iowa in uniform.

|

| Robert Bly in the 60s |

My physical at Fort Des Moines replicated the conflict among the personnel conducting it that I saw in Chicago, but this time more dramatically. My appeal physical was managed by a desk sergeant on the first floor, who was mutely if clearly sympathetic. If I wanted out, that seemed pretty ok to him.

But that decision was to be made upstairs (literally—I think it was the third floor) by a doctor, a young lieutenant who eventually told me that no matter what I brought to him, he was going to pass me. He’d been drafted out of medical school, and if he had to go, I would have to go.

This back and forth, this circuit from downstairs to upstairs with occasional trips to off-base doctors, went on for three days. I caught on to the drill early: maybe because this was an appeal, or maybe because of the desk sergeant, they were duly if not actually examining every claim I made. And so I kept making them, and they kept sending me for more tests and evaluations.

There were a couple of highlights. They sent me to a doctor elsewhere in Des Moines for another hearing test. He was elderly, and had the most primitive equipment I’d seen since my first grade hearing exam. I’d been tested several times since with the latest machinery at the University of Pittsburgh, but this guy’s idea of a hearing test was to stand behind me and ask me to repeat what he said. “One,” he said, and then moved a few feet. “Two...”

|

| Denise Levertov in 1968 |

Eventually, after three nights in the barracks and three days on the first, second and third floors, the desk sergeant was briskly amused and rather pleased to tell me that I’d essentially worn them out, and that I would be reclassified as unfit. The papers I got in the mail merely stated that my appeal—based on my hearing—had been successful.

My journey back from Fort Des Moines began with hash browns at the bus station eatery, and in the adjoining arcade I bought an old red marching band coat, Sergeant Pepper style.

It sounds like a Joseph Heller story now, but it was hell at the time. I was so traumatized and conflicted by the years and months leading up to the hours and days at Fort Des Moines that I dropped out of the Workshop, left Iowa, and wound up back in Galesburg, fulfilling my own prophecy in a poem published in the Siwasher my senior spring: “I will hide.”

Next time: Related political books, Kent State, and the Students Are Revolting takes over a dean’s office at Knox College, fifty years ago this May.